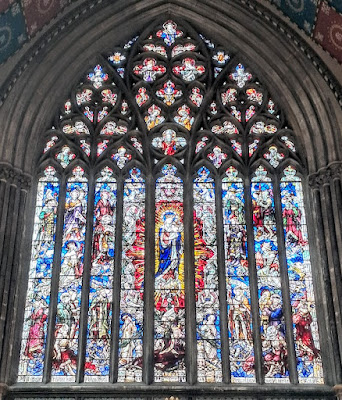

Inside Farm Street Church or the Church of the Immaculate Conception, the Jesuit-run church in Mayfair, facing the liturgical east end (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Patrick Comerford

When I was in London a few days ago, I visited half or dozen or so churches and chapels in Bloomsbury, Fitzrovia and Mayfair, and for the first time ever visited Farm Street Church or the Church of the Immaculate Conception, the Jesuit-run church in Mayfair.

Farm Street Church and has been described by Sir Simon Jenkins as ‘Gothic Revival at its most sumptuous.’ I cannot explain why I have never visited this church until now, with its interior work by Pugin, Goldie, Salviati and Eric Gill, its stained glass by Hardman of Birmingham, Evie Hone and Patrick Pollen, and its reputation for musical excellence.

Farm Street Church has been well-known for different reasons for over 175 years, including as a community welcoming converts to Roman Catholicism, famous writers, and for challenging preaching and beautiful music and art. Many people have regularly travelled long distances to worship in the church and to seek help and advice from the Jesuit community there.

Farm Street Church was designed by Joseph John Scoles, and his façade was inspired by Beauvais Cathedral (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

When the Jesuits first began looking for a site for a church in London in the 1840s, they found the site in the mews of a back street. The name Farm Street comes from Hay Hill Farm which, in the 18th century, extended from Hill Street east beyond Berkeley Square. Pope Gregory XVI approved building the church in 1843.

The Superior of the English Jesuits at the time was Father Randal Lythgoe. He originally wanted to build a church that could hold 900 people. But this was too expensive, and the church was built with a capacity of 475. It cost £5,800 to build, and this was met by private donations. Father Lythgoe laid the foundation stone in 1844. The church opened for use in 1846 and the church was officially opened by Bishop Nicholas Wiseman, later the first Archbishop of Westminster on 31 July 1849, the feast of the Jesuit founder Saint Ignatius Loyola.

The architect was Joseph John Scoles (1798-1863), who also designed the Church of Saint Francis Xavier, Liverpool, Saint Ignatius Church, Preston, and the Church of Saint James the Less and Saint Helen, Colchester. He was father of Canon Ignatius Scoles, an architect and Jesuit priest, who designed Saint Wilfrid’s Church, Preston, and the church hall at Saint James the Less and Saint Helen, Colchester.

Thomas Jackson was the builder and Henry Taylor Bulmer designed the original interior decorations. Before the official opening, The Builder described the church on 2 June 1849 as ‘a very successful specimen of modern Gothic’.

Inside Farm Street Church, facing the liturgical west, the organ and the rose window (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Because of the limited size of the plot, the church was orientated north-south rather than east-west. The plan of the church is longitudinal, consisting of a nave, aisles with chapels and the sanctuary with side chapels. The overall style is a mixture of Decorated and Flamboyant Gothic, with the west front derived from Beauvais Cathedral, and the east window from Carlisle Cathedral.

The style is Decorated Gothic and Scoles in his design of the façade was inspired by the west front of Beauvais Cathedral. The Caen stone high altar high altar was designed by AWN Pugin, with an inscription requesting prayers for the altar’s benefactor, Monica Tempest. The front panels depict the sacrifices of Abel, Noah, Melchizedek and Abraham. The reredos contains images of the 24 elders in the Book of Revelation (see Revelation 4: 10);

Above Pugin’s high altar are two Venetian mosaic panels by Antonio Salviati (1816-1890) depicting the Annunciation and the Coronation of the Virgin Mary, added in 1875, shortly after Salviati had oepned studios in London. The sanctuary walls are lined with alabaster and marble by George Goldie (1864).

The polychrome statue of Our Lady of Farm Street, by Mayer of Munich, was donated in 1868. The figure is 6 ft high, carved in wood and decorated with gilt in the engraved style.

The words of the Ave Maria (see Luke 1: 26-28) are continued along the upper walls in the church in a series of roundels completed by Filomena Monteiro in 1996.

AWN Pugin’s high altar and the two Venetian mosaic panels by Antonio Salviati (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Originally, the church had a nave, sanctuary with side chapels and only three bays of aisles. Rich furnishings were gradually installed to embellish the church. The side chapels on the south side are dedicated to Saint Aloysius, Saint Joseph and Saint Francis Xavier.

After a fire in the Blessed Sacrament Chapel in 1858, Henry Clutton rebuilt it as the Sacred Heart Chapel (1858-1863), with the assistance of John Francis Bentley (1839-1902), later the architect of Westminster Cathedral. Bentley’s other churches included Holy Rood Church, Watford.

The sanctuary floor was raised in 1864, with the east window raised correspondingly. The side aisles were added as neighbouring land became available. Clutton built the south aisle in 1876-1878, with three chapels and a porch to Farm Street. Alfred Edward Purdie added the red brick presbytery in 1886-1888, and also designed furnishings for several chapels in the 1880s and in 1905.

William Henry Romaine-Walker (1854-1940) built the north aisle in 1898–1903, with five chapels divided by internal buttresses that enclosed confessionals. The chapels and the north aisle continued to be furnished in 1903-1909: the Calvary Chapel, the Altar of the English Martyrs, the Altar of Our Lady and Saint Stanislaus, the Altar of Saint Thomas the Apostle, and the Altar of Our Lady of Sorrows.

The sanctuary walls are lined with alabaster and marble by George Goldie (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

At the same time as the north aisle was built, an additional entrance to Mount Street Gardens was added and the north-east side chapel was reconfigured by Walker as the Chapel of Saint Ignatius. The liturgical east façade became visible and accessible with the demolition of Saint George’s workhouse, which had directly abutted the site boundary, and the laying out of public gardens.

The church was remodelled in 1951 by Adrian Gilbert Scott, following the bomb damage caused during World War II. The church became the parish church of Mayfair in the Diocese of Westminster in 1966 – until then, Baptisms and weddings could not be celebrated in the church.

There were several attempts to reorder the sanctuary without altering AWN Pugin’s high altar. Broadbent, Hastings, Reid & New extended the sanctuary floor in 1980, installed a forward altar, moved the pulpit eastwards to the chancel arch, and removed the altar rail gates to the Calvary Chapel while keeping the rails.

At the same time, the roof was repaired at a cost of over £86,000. In 1987, the roof was painted to a scheme by Austin Winkley. In 1992 a fibreglass cast of Pugin’s high altar was installed as a forward altar, but has since been replaced.

The most recent restoration campaign was completed in 2007 and involved conserving the stonework on the exterior, in the sanctuary and in the Sacred Heart Chapel.

The new altar, solemnly dedicated in 2019, was carved in Carrara marble by Paul Jakeman of London and features a frieze of bunches of grapes, calling to mind the Eucharist.

The original East Window was replaced in 1912 by a new window by John Hardman of Birmingham (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

The great window in the chancel at the litrugical east end of the church was based on the east window in Carlisle Cathedral, with the theme of the Jesse Tree, tracing the family tree of Jesus back to the father of King David. The original was tarnished by pollution, and was replaced in 1912 by a new one by John Hardman of Birmingham. The old window was then cleaned and repaired and then moved to Saint Agnes Church in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec.

Hardman modified the original design of the Jesse Tree in the window to make the Madonna with the Christ Child the central figure.

The rose window at the liturgical west end by the Irish artist Evie Hone (1894-1955) depicts the instruments of Christ’s Passion. She also designed the window in the Lourdes Chapel depicting the Assumption. She once had a workshop in the courtyard at Marlay Park in Rathfarnham.

The window in the Calvary Chapel by Patrick Pollen (1928-2010), who worked with Evie Hone and Catherine O’Brien at An Túr Gloine, depicts three Jesuit English martyrs and saints: Edmund Campion, Robert Southwell and Nicholas Owen.

The window by Patrick Pollen depicting three Jesuit English martyrs: Edmund Campion, Robert Southwell and Nicholas Owen (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

In his book England’s Thousand Best Churches (1999), Sir Simon Jenkins says, ‘Not an inch of wall surface is without decoration, and this in the austere 1840s, not the colourful late-Victorian era. The right aisle carries large panels portraying the Stations of the Cross. The left aisle has side chapels and confessionals, ingeniously carved within the piers. In the west window above the gallery is excellent modern glass by Evie Hone of 1953, with the richness of colour of a Burne-Jones.’

The church opened its doors to LGBT Catholics in 2013 after the ‘Soho Masses’ came to an end after six years at the nearby Church of Our Lady of the Assumption and Saint Gregory. Archbishop Vincent Nichols attended the first of these Masses in Farm Street.

The parish also has a focus on service to the disadvantaged, especially the homeless, refugees, trafficked people and people who suffer because of the faith, and supports Jesuit and Catholic projects in the Middle East, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

William Henry Romaine-Walker built the north aisle in 1898–1903, with five chapels divided by internal buttresses (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Farm Street Church has developed a reputation for its music over the years. In the 19th century, the choir consisted only of men and boys drawn from the local Roman Catholic schools.

Between 1881 and 1916, the organist was John Francis Brewer, son of the architectural illustrator Henry William Brewer, who was just 18 when appointed.

After World War I, the choir wasunder the direction of Father John Driscoll and then Fernand Laloux, and the organist was Guy Weitz, a Belgian who had been a pupil of Charles-Marie Widor and Alexandre Guilmant. One of Weitz’s most notable students was Nicholas Danby (1935-1997) who succeeded him as the church organist in 1967. Danby’s main achievement at Farm Street was re-establishing the choir in the early 1970s, following a period of change in the late 1960s, as a fully professional ensemble.

A number of recordings were made of the music at Farm Street church were made in the 1990s. A CD of organ music was recorded at Farm Street in 2000 by David Graham and included the music of Guy Weitz. Today, the repertoire at Farm Street includes 16th century polyphony, the Viennese classical composers, 19th century romantics, 20th century and contemporary music as well as Gregorian chant.

The sanctuary was reordered on several occasions without altering AWN Pugin’s high altar (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

The Mount Street Jesuit Centre was launched in 2004 to provide adult Christian formation through prayer, worship, theological education and social justice. It offers non-residential retreats and courses in spirituality and provides a full-time GP service for homeless people.

When Heythrop College formally closed in 2019, the London Jesuit Centre was launched at the Mount Street Jesuit Centre. It includes a reading room of the Heythrop Library, with access to about 8,000 books and indirect access to most of the collection of Heythrop College. The London Jesuit Centre also provides teaching courses, spirituality, retreats and research. and residential and non-residential retreats.

The Month, a monthly review published by the Jesuits at Farm Street, was founded by Frances Margaret Taylor (1832-1900) in 1864, but closed in 2001. Thinking Faith was launched as an online journal in 2008 and publishes theological papers as well as papers on philosophy, spirituality, the arts, poetry, culture, Biblical studies, political and social issues and current affairs.

King Charles III attended a special Advent service at Farm Street Church organised by Aid to the Church in Need (ACN), a charity that supports persecuted Christians.

• Mass times on Sundays are at 8 am, 9:30 and 11, with a young adults Mass at 7 pm. Weekday Masses, Monday to Friday, are at 8 am, 1:05 pm and 6 pm. Saturday Masses are at 10 am and 6 pm (Saturday Vigil).

The Homeless Jesus, a sculpture in Farm Street Church by Timothy Schmalz (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Stations XIII and XIV in the Stations of the Cross in Farm Street Church (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

The polychrome statue of Our Lady of Farm Street, by Mayer of Munich, was donated in 1868 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

The liturgical east façade facing Mount Street Gardens became accessible with the demolition of Saint George’s workhouse (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

▼

22 June 2025

Daily prayer in Ordinary Time 2025:

44, Sunday 22 June 2025,

First Sunday after Trinity (Trinity I)

‘For a long time … he did not live in a house but in the tombs’ (Luke 8: 27) … the Lycian rock tombs in the cliff faces above Fethiye in Turkey (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

We are in Ordinary Time in the Church Calendar, and today is the First Sunday after Trinity (Trinity I, 22 June 2025). Later this morning, I am reading one of the lessons at the Parish Eucharist in Saint Mary and Saint Giles Church, Stony Stratford.

Before today begins, however, I am taking some quiet time this morning to give thanks, to reflect, to pray and to read in these ways:

1, reading today’s Gospel reading;

2, a short reflection;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary;

4, the Collects and Post-Communion prayer of the day.

‘Now there on the hillside a large herd of swine was feeding’ (Luke 8: 32) … sculptures of pigs throughout Tamworth celebrate the political achievements of Sir Robert Peel, including ‘bread for the millions’ and ‘religious tolerance’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Luke 8: 26-39 (NRSVA):

26 Then they [Jesus and the Disciples] arrived at the country of the Gerasenes, which is opposite Galilee. 27 As he stepped out on land, a man of the city who had demons met him. For a long time he had worn no clothes, and he did not live in a house but in the tombs. 28 When he saw Jesus, he fell down before him and shouted at the top of his voice, ‘What have you to do with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God? I beg you, do not torment me’ – 29 for Jesus had commanded the unclean spirit to come out of the man. (For many times it had seized him; he was kept under guard and bound with chains and shackles, but he would break the bonds and be driven by the demon into the wilds.) 30 Jesus then asked him, ‘What is your name?’ He said, ‘Legion’; for many demons had entered him. 31 They begged him not to order them to go back into the abyss.

32 Now there on the hillside a large herd of swine was feeding; and the demons begged Jesus to let them enter these. So he gave them permission. 33 Then the demons came out of the man and entered the swine, and the herd rushed down the steep bank into the lake and was drowned.

34 When the swineherds saw what had happened, they ran off and told it in the city and in the country. 35 Then people came out to see what had happened, and when they came to Jesus, they found the man from whom the demons had gone sitting at the feet of Jesus, clothed and in his right mind. And they were afraid. 36 Those who had seen it told them how the one who had been possessed by demons had been healed. 37 Then all the people of the surrounding country of the Gerasenes asked Jesus to leave them; for they were seized with great fear. So he got into the boat and returned. 38 The man from whom the demons had gone begged that he might be with him; but Jesus sent him away, saying, 39 ‘Return to your home, and declare how much God has done for you.’ So he went away, proclaiming throughout the city how much Jesus had done for him.

‘So he got into the boat and returned’ (Luke 8: 37) … a boat by the banks of the River Great Ouse in Old Stratford, Northamptonshire (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Today’s Reflection:

Our Gospel story (Luke 8: 26-39) is set by the Sea of Galilee. After Jesus calms a storm on the lake (Luke 8: 22-25), he and the disciples arrive on the other side and travel deep into Gentile territory, perhaps 30 or 50 km on the other side of the lake. The area is known as the Decapolis, dominated by ten Greek-speaking cities.

Imagine you are among the first group of people in the Early Church who begin to read this story. You would expect the story to unfold with Jesus and Disciples seeking out distant family members, staying with nice, upright people, perhaps visiting the local synagogue maintained by a tiny Jewish minority presence in one of the towns.

But from the very moment they get off the boat, they are in a place and among a people they would have regarded as unclean: these Gentile people are ritually ‘unclean,’ the man has an ‘unclean’ spirit, he is naked or a person of visible and public shame, he lives among the tombs, which are ritually unclean … and the pigs are unclean too.

This episode plays a key role in the theory of the ‘Scapegoat’ put forward by the French literary critic René Girard (1923-2015). The opposition of the entire city to the one man possessed by demons is the typical template for a scapegoat. Girard notes that, in the demoniac’s self-mutilation, he seems to imitate the way the villagers might have tried to stone him and to cast him out of their society.

For their part, the villagers in their reaction to Christ show they are not really concerned with the good of the possessed man. He acts as a scapegoat, and they can project anything they dislike about themselves onto him. Why kill him when he has such a useful function in their enclosed society?

Now, I do not in any way want to diminish or dismiss the real power of evil and the hold that it can have over people.

But in René Girard’s take on this story, the uneasy truce that the Gadarenes and the demoniac have worked out means he serves a ritual purpose for them so long as he is alive and perceived as being possessed.

But when Jesus steps off the boat, he brings with him a stronger spiritual power: love and healing, forgiveness and acceptance, are stronger than stoning, chaining, or scapegoating. And the pigs rushing headlong over the cliffside tell a story that is not so much about cruelty to animals but saying we need to put behind us all that we regard as unclean or sinful in others and need to start accepting ourselves.

After this episode, the man not only sits ‘at the feet of Jesus,’ as disciples did, but he becomes a missionary to other Gentiles. This is a story of dramatic transformation.

Look at the changes in this man’s life: he moves from outside the city to inside it; he moves from living in tombs and being driven into the desert to being alive in a house; he moves from nakedness to being clothed, from being demented to being of sound mind.

He moves from destructive isolation to being part of a nurturing, human community. He moves from being expelled from the religious community to being part of the Church and proclaiming the good news. This is real mission, the sort of mission I hope to hear about this week with USPG.

‘Return to your home, and declare how much God has done for you’ (Luke 8: 39).

Saint Luke here uses the word οἶκος (oikos), which means a house, an inhabited house, even a palace or the house of God, as opposed to δόμος (domos), the word used for a house as a domestic home. Those who live there now form one family or household, and this comes to mean the family of God or the Church (for examples, see I Timothy 3: 15; I Peter 4: 17, and Hebrews 3: 2, 5).

The outsider, the person seen as unclean and defiled, the scapegoat, is restored to a full place in the Church, in God’s household, in God’s family.

Who do we see as Scapegoats today, as outsiders to be pushed to the margins, so that we can maintain the purity of our family, church or society?

Who do we expose and shame so that we can maintain the appearance of our own purity?

Are these the very people who might bring the good news to people on the margins, inviting them into the household of God?

‘For a long time … he did not live in a house but in the tombs’ (Luke 8: 27) … in the graveyard between Koutouloufari and Piskopiano in Crete (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2024)

Today’s Prayers (Sunday 22 June 2025, Trinity I):

‘Windrush Day’ is the theme this week (22-28 June) in Pray with the World Church, the prayer diary of the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel). This theme is introduced today with reflections by Rachael Anderson, former Senior Communications and Engagement Manager, USPG:

‘Windrush Day marks the anniversary of the arrival of HMT Empire Windrush in Tilbury on the south coast of the UK. On board were hundreds of Caribbean people who had left the West Indies owing to the call from Britain – the ‘mother country’ – to help rebuild a war-ravaged country.

‘Although they were responding to a call for help, the reality for many of the Windrush generation was a new life subject to hostility, rejection and racism. Shamefully this took place on streets, in neighbourhoods and even at the doors of parish churches – a place where they should have felt welcomed and at home, able to worship God alongside other Christians. It is painfully ironic that it was also the Church of England that had once taken the Anglican faith to the Caribbean – often preaching in the very plantations where enslaved people were held in bondage. A double act of rejection.

‘It is in this reality that the Gospel speaks a powerful and compelling truth. We are all sisters and brothers in Christ, and we all have a responsibility to ensure that our churches are safe places and spaces of belonging for people of every nation and every language who come to church to worship and serve God. It is not just about parish church congregations; the Church of England needs to continue to make the necessary institutional and systemic changes to ensure a more diverse church at every level and recognise that honesty and openness is also key to its flourishing in society.’

The USPG prayer diary today (Sunday 22 June 2025, Trinity I, Windrush Day) invites us to pray:

Loving Lord, we thank you for the amazing contribution of the Windrush generation to our communities and workplaces, and to your Church in our land.

The Collect:

O God,

the strength of all those who put their trust in you,

mercifully accept our prayers

and, because through the weakness of our mortal nature

we can do no good thing without you,

grant us the help of your grace,

that in the keeping of your commandments

we may please you both in will and deed;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

The Post-Communion Prayer:

Eternal Father,

we thank you for nourishing us

with these heavenly gifts:

may our communion strengthen us in faith,

build us up in hope,

and make us grow in love;

for the sake of Jesus Christ our Lord.

Additional Collect:

God of truth,

help us to keep your law of love

and to walk in ways of wisdom,

that we may find true life

in Jesus Christ your Son.

Yesterday’s Reflections

Continued Tomorrow

‘Now there on the hillside a large herd of swine was feeding’ (Luke 8: 32) … The Pig, a pub sign on Tamworth Street in Lichfield, now the Beacon (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2024)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Patrick Comerford

We are in Ordinary Time in the Church Calendar, and today is the First Sunday after Trinity (Trinity I, 22 June 2025). Later this morning, I am reading one of the lessons at the Parish Eucharist in Saint Mary and Saint Giles Church, Stony Stratford.

Before today begins, however, I am taking some quiet time this morning to give thanks, to reflect, to pray and to read in these ways:

1, reading today’s Gospel reading;

2, a short reflection;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary;

4, the Collects and Post-Communion prayer of the day.

‘Now there on the hillside a large herd of swine was feeding’ (Luke 8: 32) … sculptures of pigs throughout Tamworth celebrate the political achievements of Sir Robert Peel, including ‘bread for the millions’ and ‘religious tolerance’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Luke 8: 26-39 (NRSVA):

26 Then they [Jesus and the Disciples] arrived at the country of the Gerasenes, which is opposite Galilee. 27 As he stepped out on land, a man of the city who had demons met him. For a long time he had worn no clothes, and he did not live in a house but in the tombs. 28 When he saw Jesus, he fell down before him and shouted at the top of his voice, ‘What have you to do with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God? I beg you, do not torment me’ – 29 for Jesus had commanded the unclean spirit to come out of the man. (For many times it had seized him; he was kept under guard and bound with chains and shackles, but he would break the bonds and be driven by the demon into the wilds.) 30 Jesus then asked him, ‘What is your name?’ He said, ‘Legion’; for many demons had entered him. 31 They begged him not to order them to go back into the abyss.

32 Now there on the hillside a large herd of swine was feeding; and the demons begged Jesus to let them enter these. So he gave them permission. 33 Then the demons came out of the man and entered the swine, and the herd rushed down the steep bank into the lake and was drowned.

34 When the swineherds saw what had happened, they ran off and told it in the city and in the country. 35 Then people came out to see what had happened, and when they came to Jesus, they found the man from whom the demons had gone sitting at the feet of Jesus, clothed and in his right mind. And they were afraid. 36 Those who had seen it told them how the one who had been possessed by demons had been healed. 37 Then all the people of the surrounding country of the Gerasenes asked Jesus to leave them; for they were seized with great fear. So he got into the boat and returned. 38 The man from whom the demons had gone begged that he might be with him; but Jesus sent him away, saying, 39 ‘Return to your home, and declare how much God has done for you.’ So he went away, proclaiming throughout the city how much Jesus had done for him.

‘So he got into the boat and returned’ (Luke 8: 37) … a boat by the banks of the River Great Ouse in Old Stratford, Northamptonshire (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Today’s Reflection:

Our Gospel story (Luke 8: 26-39) is set by the Sea of Galilee. After Jesus calms a storm on the lake (Luke 8: 22-25), he and the disciples arrive on the other side and travel deep into Gentile territory, perhaps 30 or 50 km on the other side of the lake. The area is known as the Decapolis, dominated by ten Greek-speaking cities.

Imagine you are among the first group of people in the Early Church who begin to read this story. You would expect the story to unfold with Jesus and Disciples seeking out distant family members, staying with nice, upright people, perhaps visiting the local synagogue maintained by a tiny Jewish minority presence in one of the towns.

But from the very moment they get off the boat, they are in a place and among a people they would have regarded as unclean: these Gentile people are ritually ‘unclean,’ the man has an ‘unclean’ spirit, he is naked or a person of visible and public shame, he lives among the tombs, which are ritually unclean … and the pigs are unclean too.

This episode plays a key role in the theory of the ‘Scapegoat’ put forward by the French literary critic René Girard (1923-2015). The opposition of the entire city to the one man possessed by demons is the typical template for a scapegoat. Girard notes that, in the demoniac’s self-mutilation, he seems to imitate the way the villagers might have tried to stone him and to cast him out of their society.

For their part, the villagers in their reaction to Christ show they are not really concerned with the good of the possessed man. He acts as a scapegoat, and they can project anything they dislike about themselves onto him. Why kill him when he has such a useful function in their enclosed society?

Now, I do not in any way want to diminish or dismiss the real power of evil and the hold that it can have over people.

But in René Girard’s take on this story, the uneasy truce that the Gadarenes and the demoniac have worked out means he serves a ritual purpose for them so long as he is alive and perceived as being possessed.

But when Jesus steps off the boat, he brings with him a stronger spiritual power: love and healing, forgiveness and acceptance, are stronger than stoning, chaining, or scapegoating. And the pigs rushing headlong over the cliffside tell a story that is not so much about cruelty to animals but saying we need to put behind us all that we regard as unclean or sinful in others and need to start accepting ourselves.

After this episode, the man not only sits ‘at the feet of Jesus,’ as disciples did, but he becomes a missionary to other Gentiles. This is a story of dramatic transformation.

Look at the changes in this man’s life: he moves from outside the city to inside it; he moves from living in tombs and being driven into the desert to being alive in a house; he moves from nakedness to being clothed, from being demented to being of sound mind.

He moves from destructive isolation to being part of a nurturing, human community. He moves from being expelled from the religious community to being part of the Church and proclaiming the good news. This is real mission, the sort of mission I hope to hear about this week with USPG.

‘Return to your home, and declare how much God has done for you’ (Luke 8: 39).

Saint Luke here uses the word οἶκος (oikos), which means a house, an inhabited house, even a palace or the house of God, as opposed to δόμος (domos), the word used for a house as a domestic home. Those who live there now form one family or household, and this comes to mean the family of God or the Church (for examples, see I Timothy 3: 15; I Peter 4: 17, and Hebrews 3: 2, 5).

The outsider, the person seen as unclean and defiled, the scapegoat, is restored to a full place in the Church, in God’s household, in God’s family.

Who do we see as Scapegoats today, as outsiders to be pushed to the margins, so that we can maintain the purity of our family, church or society?

Who do we expose and shame so that we can maintain the appearance of our own purity?

Are these the very people who might bring the good news to people on the margins, inviting them into the household of God?

‘For a long time … he did not live in a house but in the tombs’ (Luke 8: 27) … in the graveyard between Koutouloufari and Piskopiano in Crete (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2024)

Today’s Prayers (Sunday 22 June 2025, Trinity I):

‘Windrush Day’ is the theme this week (22-28 June) in Pray with the World Church, the prayer diary of the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel). This theme is introduced today with reflections by Rachael Anderson, former Senior Communications and Engagement Manager, USPG:

‘Windrush Day marks the anniversary of the arrival of HMT Empire Windrush in Tilbury on the south coast of the UK. On board were hundreds of Caribbean people who had left the West Indies owing to the call from Britain – the ‘mother country’ – to help rebuild a war-ravaged country.

‘Although they were responding to a call for help, the reality for many of the Windrush generation was a new life subject to hostility, rejection and racism. Shamefully this took place on streets, in neighbourhoods and even at the doors of parish churches – a place where they should have felt welcomed and at home, able to worship God alongside other Christians. It is painfully ironic that it was also the Church of England that had once taken the Anglican faith to the Caribbean – often preaching in the very plantations where enslaved people were held in bondage. A double act of rejection.

‘It is in this reality that the Gospel speaks a powerful and compelling truth. We are all sisters and brothers in Christ, and we all have a responsibility to ensure that our churches are safe places and spaces of belonging for people of every nation and every language who come to church to worship and serve God. It is not just about parish church congregations; the Church of England needs to continue to make the necessary institutional and systemic changes to ensure a more diverse church at every level and recognise that honesty and openness is also key to its flourishing in society.’

The USPG prayer diary today (Sunday 22 June 2025, Trinity I, Windrush Day) invites us to pray:

Loving Lord, we thank you for the amazing contribution of the Windrush generation to our communities and workplaces, and to your Church in our land.

The Collect:

O God,

the strength of all those who put their trust in you,

mercifully accept our prayers

and, because through the weakness of our mortal nature

we can do no good thing without you,

grant us the help of your grace,

that in the keeping of your commandments

we may please you both in will and deed;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

The Post-Communion Prayer:

Eternal Father,

we thank you for nourishing us

with these heavenly gifts:

may our communion strengthen us in faith,

build us up in hope,

and make us grow in love;

for the sake of Jesus Christ our Lord.

Additional Collect:

God of truth,

help us to keep your law of love

and to walk in ways of wisdom,

that we may find true life

in Jesus Christ your Son.

Yesterday’s Reflections

Continued Tomorrow

‘Now there on the hillside a large herd of swine was feeding’ (Luke 8: 32) … The Pig, a pub sign on Tamworth Street in Lichfield, now the Beacon (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2024)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org