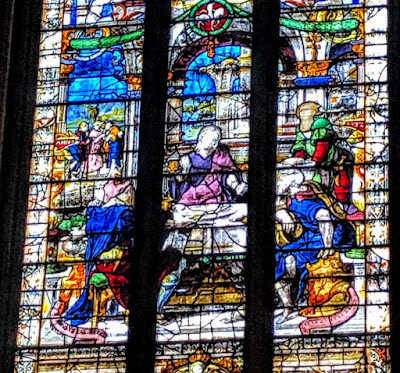

Christ in the home of Mary, Martha and Lazarus … a panel in the Herkenrode glass windows in the Lady Chapel in Lichfield Cathedral (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

Patrick Comerford

During my ‘mini-retreat’ in Lichfield this week, I have been staying at the Hedgehog Vintage Inn on the northern edges of the cathedral city, close to the junction of Stafford Road and Cross in Hand Lane.

It has been a pleasant, 20-minute stroll along Beacon Street into the cathedral each day, to join in the Mid-Day Eucharist and Evening Prayer or Choral Evensong.

The Hedgehog stands in its own grounds, in a tranquil, semi-rural setting. Since I last stayed here, the house, bar and dining area have been refurbished, but it still retains all the charm of a country house that has become a boutique hotel.

A new framed display near the bar recalls that this was once Lyncroft House, and that it was the home of the Italian-born composer Muzio Clementi (1752-1832), who rented the house from the Earl of Lichfield after his last public performance in 1828, and moved to Lichfield with his wife and family. He is buried in Westminster Abbey.

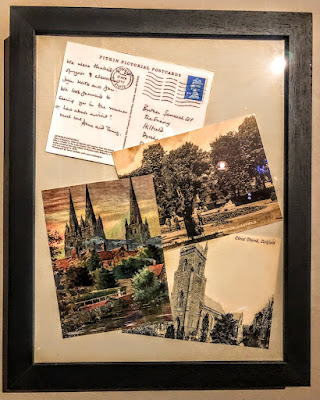

Framed postcards from Lichfield at a window in the Hedgehog Vintage Inn (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

In the window area, where I have been sitting for a drink each evening after dinner are two framed collections of postcards. One collection includes postcards showing the house in Lichfield where Samuel Johnson was born, and another depicts Samuel Johnson’s statue in the Market Place.

A second collection of postcards includes Lichfield Cathedral, Beacon Gardens and Christ Church, Lichfield, and the back of a postcard with a personal message to Brother Samuel SSF, congratulating him on becoming the Guardian of Hilfield Priory in Dorchester.

The image on the other side of the postcard cannot be seen, but the caption says it is a photograph by Sonia Halliday and Laura Lushington of a panel in the central East Window in the Lady Chapel in Lichfield Cathedral.

The windows of the Lady Chapel contain some of the finest mediaeval Flemish Painted Glass. They date from the 1530s and were reinstalled in 2015. The seven Renaissance Herkenrode glass windows represent the greatest collection of unrestored 16th century Flemish glass anywhere.

The windows were bought by Lichfield Cathedral to replace the mediaeval stained destroyed during the English Civil War in the mid-17th century. The glass came from the Abbey of Herkenrode, now in Belgium, in 1801. They were bought by Sir Brooke Boothby when the abbey was dissolved during the Napoleonic Wars, and they were then sold on to the cathedral for the same price and were brought to England in 1803.

The postcard to Brother Samuel is obviously illustrated with the panel above the altar in the Lady Chapel showing Christ as the guest in the home of Mary, Martha and Lazarus in Bethany. I have been sitting under this panel in the Lady Chapel each day this week.

Autumn sunshine at the Hedgehog in Lichfield (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

14 October 2021

Praying in Ordinary Time 2021:

138, Saint Mary’s Church, Ennis

Saint Mary’s, the Friary Church in Ennis, Co Clare, was designed by William Reginald Carroll and incorporates an earlier church by Patrick Sexton (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

I returned from Lichfield late last night after a three-day break this week, staying at the Hedgehog Vintage Inn on Stafford Road, enjoying walks in the countryside, following the daily cycle of prayer in Lichfield Cathedral, meeting some old friends, and finding some ‘down time.’

I am on my way back to Askeaton, Co Limerick, later today. But, before the day begins, I am taking a little time this morning for prayer, reflection and reading. Each morning in the time in the Church Calendar known as Ordinary Time, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, photographs of a church or place of worship;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

My theme for these few weeks is churches in the Franciscan (and Capuchin) tradition. My photographs this morning (14 October 2021) are from Saint Mary’s, the Friary Church in Ennis, Co Clare.

A plaque in the church remembers past members of the Franciscan community in Ennis (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The old Franciscan Friary in Ennis, Co Clare, is now an archaeological site managed by the Office of Public Works. But the Franciscans maintain a living presence in the town in their friary just around the corner, on Francis Street.

Following a decree under the Penal Laws requiring priests who were members of religious orders to leave Ireland, at least four Franciscan friars in the Ennis area decided to register as parish clergy after 1697, and the friars continued to live among they people in Co Clare.

After living a hidden life outside the town for a time in the 17th and 18th century, the Franciscans began to return to Ennis, and they were living again as a community in Lysaght’s Lane by 1800.

The friars then moved to Bow Lane, where they opened a new chapel and friary on 12 December 1830.

The Franciscan Provincial threatened to close the friary in Ennis in 1853 unless conditions were improved. The Franciscan community in Ennis responded by buying the present site at Willow Bank House on Francis Street and in 1854 Patrick Sexton designed a new chapel.

The architect Patrick Sexton was active in Ennis from the 1850s until at least 1880. His new cruciform chapel was built by the Ennis builder William Carroll between June 1854 and December 1855.

The first Mass in the new church was celebrated on 1 January 1856, and the church was dedicated as the Church of the Immaculate Conception on 10 September 1856.

At the end of the 19th century, a new friary church, designed by William Reginald Carroll (1850-1910) and incorporating Sexton’s earlier church, was built in the Gothic Revival style in 1892.

The Ennis-born architect and civil engineer William Reginald Carroll was born in 1850, a younger son of William Carroll, who had built the earlier church in the 1850s.

Carroll designed the new friary church in Ennis in the 14th-century Gothic style, with a nave, apse, two side chapels and a tower. The altar was designed by the Dublin-based monumental sculptor, James Pearse (1839-1900), father of the 1916 leader, Padraic Pearse (1879-1916).

Pearse, who also designed the reredos in Saint Mary’s Cathedral, Limerick, was born in London in 1839. He was brought to Dublin from Birmingham by Charles William Harrison around 1860 as the foreman of his monumental sculpture workshop at 178 Great Brunswick Street. Pearse, who was a Unitarian, died suddenly in 1900 in Birmingham while he was visiting his brother.

The church was built by a local builder, Dan Shanks, at a cost of £11,000, and was dedicated on 11 June 1892.

The church is a T-plan, gable-fronted church, with a polygonal apse, a tower to the west, and a connecting block that leads to the neighbouring friary.

A statue of the Virgin Mary stands in a niche on the façade and is flanked by lancet windows with stone tracery, and with a quatrefoil and hood moulding above. Paired lancet windows are set between the buttresses.

Inside, the church has an open timber roof, with tongue and groove sheeting. There are four polished granite columns with carved stylised ivy capitals that divide the nave from the transepts. The stained-glass windows are by Earley.

The foundation stone of the earlier church on the site is set in the grotto beside the church.

The architect William Reginal Carroll moved from Ennis to Ewell in Surrey around 1899 and soon after to Belgium, living first in Bruges and then in Brussels. He died at his home in Brussels on 8 April 1910.

Meanwhile, a new friary was completed in 1877, and the Franciscan house in Ennis remained the official novitiate of the Irish province until 1902.

The friary site includes the site of the birthplace of William Mulready (1786-1863), the Ennis-born artist who studied at the Royal Academy and designed the first penny postage envelope, introduced by the Royal Mail at the same time as the ‘Penny Black’ stamp in May 1840.

Inside the church designed by William Reginald Carroll in the 14th-century Gothic style (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Luke 11: 47-54 (NRSVA):

[Jesus said:] 47 ‘Woe to you! For you build the tombs of the prophets whom your ancestors killed. 48 So you are witnesses and approve of the deeds of your ancestors; for they killed them, and you build their tombs. 49Therefore also the Wisdom of God said, “I will send them prophets and apostles, some of whom they will kill and persecute”, 50 so that this generation may be charged with the blood of all the prophets shed since the foundation of the world, 51 from the blood of Abel to the blood of Zechariah, who perished between the altar and the sanctuary. Yes, I tell you, it will be charged against this generation. 52 Woe to you lawyers! For you have taken away the key of knowledge; you did not enter yourselves, and you hindered those who were entering.’

53 When he went outside, the scribes and the Pharisees began to be very hostile towards him and to cross-examine him about many things, 54 lying in wait for him, to catch him in something he might say.

The altar was designed by the Dublin-based monumental sculptor, James Pearse (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (14 October 2021) invites us to pray:

Let us pray for the Church of South India’s Focus 9/99 programme, centring children in the life of the Church.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

A rose window in a side transept (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Patrick Comerford

I returned from Lichfield late last night after a three-day break this week, staying at the Hedgehog Vintage Inn on Stafford Road, enjoying walks in the countryside, following the daily cycle of prayer in Lichfield Cathedral, meeting some old friends, and finding some ‘down time.’

I am on my way back to Askeaton, Co Limerick, later today. But, before the day begins, I am taking a little time this morning for prayer, reflection and reading. Each morning in the time in the Church Calendar known as Ordinary Time, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, photographs of a church or place of worship;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

My theme for these few weeks is churches in the Franciscan (and Capuchin) tradition. My photographs this morning (14 October 2021) are from Saint Mary’s, the Friary Church in Ennis, Co Clare.

A plaque in the church remembers past members of the Franciscan community in Ennis (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The old Franciscan Friary in Ennis, Co Clare, is now an archaeological site managed by the Office of Public Works. But the Franciscans maintain a living presence in the town in their friary just around the corner, on Francis Street.

Following a decree under the Penal Laws requiring priests who were members of religious orders to leave Ireland, at least four Franciscan friars in the Ennis area decided to register as parish clergy after 1697, and the friars continued to live among they people in Co Clare.

After living a hidden life outside the town for a time in the 17th and 18th century, the Franciscans began to return to Ennis, and they were living again as a community in Lysaght’s Lane by 1800.

The friars then moved to Bow Lane, where they opened a new chapel and friary on 12 December 1830.

The Franciscan Provincial threatened to close the friary in Ennis in 1853 unless conditions were improved. The Franciscan community in Ennis responded by buying the present site at Willow Bank House on Francis Street and in 1854 Patrick Sexton designed a new chapel.

The architect Patrick Sexton was active in Ennis from the 1850s until at least 1880. His new cruciform chapel was built by the Ennis builder William Carroll between June 1854 and December 1855.

The first Mass in the new church was celebrated on 1 January 1856, and the church was dedicated as the Church of the Immaculate Conception on 10 September 1856.

At the end of the 19th century, a new friary church, designed by William Reginald Carroll (1850-1910) and incorporating Sexton’s earlier church, was built in the Gothic Revival style in 1892.

The Ennis-born architect and civil engineer William Reginald Carroll was born in 1850, a younger son of William Carroll, who had built the earlier church in the 1850s.

Carroll designed the new friary church in Ennis in the 14th-century Gothic style, with a nave, apse, two side chapels and a tower. The altar was designed by the Dublin-based monumental sculptor, James Pearse (1839-1900), father of the 1916 leader, Padraic Pearse (1879-1916).

Pearse, who also designed the reredos in Saint Mary’s Cathedral, Limerick, was born in London in 1839. He was brought to Dublin from Birmingham by Charles William Harrison around 1860 as the foreman of his monumental sculpture workshop at 178 Great Brunswick Street. Pearse, who was a Unitarian, died suddenly in 1900 in Birmingham while he was visiting his brother.

The church was built by a local builder, Dan Shanks, at a cost of £11,000, and was dedicated on 11 June 1892.

The church is a T-plan, gable-fronted church, with a polygonal apse, a tower to the west, and a connecting block that leads to the neighbouring friary.

A statue of the Virgin Mary stands in a niche on the façade and is flanked by lancet windows with stone tracery, and with a quatrefoil and hood moulding above. Paired lancet windows are set between the buttresses.

Inside, the church has an open timber roof, with tongue and groove sheeting. There are four polished granite columns with carved stylised ivy capitals that divide the nave from the transepts. The stained-glass windows are by Earley.

The foundation stone of the earlier church on the site is set in the grotto beside the church.

The architect William Reginal Carroll moved from Ennis to Ewell in Surrey around 1899 and soon after to Belgium, living first in Bruges and then in Brussels. He died at his home in Brussels on 8 April 1910.

Meanwhile, a new friary was completed in 1877, and the Franciscan house in Ennis remained the official novitiate of the Irish province until 1902.

The friary site includes the site of the birthplace of William Mulready (1786-1863), the Ennis-born artist who studied at the Royal Academy and designed the first penny postage envelope, introduced by the Royal Mail at the same time as the ‘Penny Black’ stamp in May 1840.

Inside the church designed by William Reginald Carroll in the 14th-century Gothic style (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Luke 11: 47-54 (NRSVA):

[Jesus said:] 47 ‘Woe to you! For you build the tombs of the prophets whom your ancestors killed. 48 So you are witnesses and approve of the deeds of your ancestors; for they killed them, and you build their tombs. 49Therefore also the Wisdom of God said, “I will send them prophets and apostles, some of whom they will kill and persecute”, 50 so that this generation may be charged with the blood of all the prophets shed since the foundation of the world, 51 from the blood of Abel to the blood of Zechariah, who perished between the altar and the sanctuary. Yes, I tell you, it will be charged against this generation. 52 Woe to you lawyers! For you have taken away the key of knowledge; you did not enter yourselves, and you hindered those who were entering.’

53 When he went outside, the scribes and the Pharisees began to be very hostile towards him and to cross-examine him about many things, 54 lying in wait for him, to catch him in something he might say.

The altar was designed by the Dublin-based monumental sculptor, James Pearse (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (14 October 2021) invites us to pray:

Let us pray for the Church of South India’s Focus 9/99 programme, centring children in the life of the Church.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

A rose window in a side transept (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)