Children at the Ukrainian Space daycare programme in Budapest celebrate Western Epiphany and Ukrainian Christmas (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

Patrick Comerford

Amber Jackson from the diocese communications team in the Diocese of Europe and Patrick Comerford from USPG are visiting Anglican chaplaincies in Hungary and Finland to see how they are supporting Ukrainian refugees with funding from the joint Ukraine appeal.

Patrick Comerford visits the Ukrainian Space daycare programme in central Budapest

The Feast of the Epiphany in the Western Church coincides with the Ukrainian Orthodox celebrations of Christmas Eve.

The children at the Ukrainian Space daycare programme in the heart of Budapest marked the coincidence this week of these two days with a nativity puppet show that began with the story of the Three Kings from the East following the star to Bethlehem.

On their way, they meet King Herod, a despotic ruler who pretends he too wants to pay homage to the new-born child while he harbours a plot to kill innocent children.

The Ukrainian children and parents could hardly have failed to recognise the comparison between the evil intentions of Herod and Putin’s plots that have forced them to flee their own home country. Nor could they have failed to compare the journey of the Wise Men from the East and the journey refugee families have made in the past year from Ukraine in the East to seek safety in Hungary and other countries to the West of Ukraine.

The Ukrainian Space daycare programme in Budapest offers schooling in Ukrainian to about 20 children between the ages of 8 and 16. The project also provides parental networking opportunities, psychological counselling, and language tuition for all ages in Hungarian, English and other Western languages.

The project has received grants from the Bishop’s Refugee Appeal in the Diocese in Europe and USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel), through the efforts of the Revd Dr Frank Hegedus, the priest and chaplain at Saint Margaret’s Anglican Church in Budapest.

The director of Ukrainian Space, Vladimir Pukish, speaks of how the needs of schoolgoing children were identified immediately as Ukrainian refugees began to pour into Hungary when Russia invaded Ukraine a year ago and war broke out.

He says most of the children are attending Hungarian schools in the morning and often keep up with their Ukrainian education back home through online facilities. The project helps them to integrate into local schools.

Father Frank explains how grants channelled through Saint Margaret’s have also provided food and drinks for children and parents during regular breaks and given the children opportunities for sightseeing views to museums and other centres in Budapest.

Grants have also helped meet staff costings, psychological support and pet therapy.

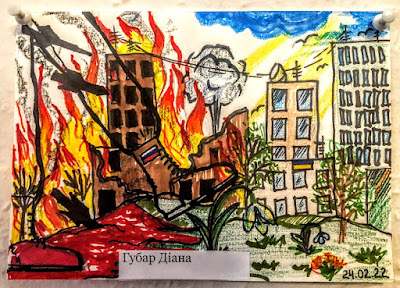

A collection of paintings on the walls illustrate the horrors of war these children have witnessed, but also depict their hope for the future.

Many refugees have already moved on from Hungary to other countries. I asked how many families hoped to go home when the war ends. ‘They have nothing to go back for,’ Father Frank explains, with sadness in his eyes. ‘They have lost not just their homes, but their entire towns and cities.’

(Revd Canon Professor) Patrick Comerford is a former Trustee of USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel) and blogs at www.patrickcomerford.com

Children’s paintings illustrate the horrors of war they have seen in Ukraine (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

07 January 2023

‘No-one expected the war to go on for this long’:

a shelter in Budapest helps Ukrainian refugees

‘No-one expected the war to go on for this long,’ Ákos Surányi, head of staff, Menedékház (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

Patrick Comerford

Amber Jackson from the diocese communications team in the Diocese in Europe and Patrick Comerford from USPG are visiting Anglican chaplaincies in Hungary and Finland to see how they are supporting Ukrainian refugees with funding from the joint Ukraine appeal.

Patrick Comerford visits a centre for homeless people in Budapest that has provided shelter for Ukrainian refugees

Ever since the Russians invaded Ukraine a year ago, refugees have been pouring across the borders of Hungary and other neighbouring countries, seeking shelter and compassion.

The Menedékház Foundation, on the outskirts of Budapest, was in a strong position to deal with the crisis from the very beginning.

Menedékház is a refuge or home for homeless families with children, and for the past 12 years it has been housed in a former army barracks half an hour from the centre of the Hungarian capital.

The head of staff, Ákos Surányi, who showed us around the facilities, says Menedékház was expecting a large number of refugee families and children when the war began, and it was well-placed to deal with the crisis as it began to unfold.

Ákos explains how the foundation has been responding for years to the needs of elderly and disabled people and families who lose their family homes and of homeless people on the streets of Budapest.

Within weeks of the war breaking out last year, Menedékház was coping with the first wave of refugees from Eastern Ukraine. They included both ethnic Ukrainians and Russian-speaking refugees from places like Donbas and Donetsk.

Doctors, nurses, teachers and other professionals volunteered their expertise, and local people donated hampers and food. Grants came from the Bishop’s Refugee Appeal in the Diocese in Europe and USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel), through the efforts of the Revd Dr Frank Hegedus, the priest and chaplain at Saint Margaret’s Anglican Church in Budapest.

Russian-speakers and Ukrainians came together in sharing their compassion for each other, understanding they were all victims of the war.

About 20 families found shelter and accommodation with Menedékház before many of the people in this first group of refugees were able to move on to other countries like Germany, Italy and the UK.

By May, a second group of up to 150 refugees from western Ukraine were being helped by the foundation.

‘No-one expected the war to go on for this long,’ Ákos says. ‘All refugees want to move on, and there are no refugees here now,’ he explains. But they are ready to take more refugee families again.

His optimism is admirable. As he explains, Menedékház is facing imminent closure. The war has also brought spiraling fuel costs and rapidly rising gas, insurance and electricity bills. The war has also played havoc with Hungary’s inflation, and the foundation is facing increasing rent demands and bills that have increased eight-fold.

Despite its success in coping with refugees from Ukraine over the past year, he predicts Menedékház is facing a major financial crisis within weeks, possibly by March. In the face of this uncertainty and possible closure, the centre continues its projects with homeless families and disabled people and with marginalised teenage boys from deprived areas in inner city Budapest.

‘As long as Menedékház continues its work, it has the support of Saint Margaret’s,’ Father Frank says with hope.

(Revd Canon Professor) Patrick Comerford is a former Trustee of USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel) and blogs at www.patrickcomerford.com

Hope springs eternal … a wall painting in the shelter at Menedékház Foundation, Budapest (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

Patrick Comerford

Amber Jackson from the diocese communications team in the Diocese in Europe and Patrick Comerford from USPG are visiting Anglican chaplaincies in Hungary and Finland to see how they are supporting Ukrainian refugees with funding from the joint Ukraine appeal.

Patrick Comerford visits a centre for homeless people in Budapest that has provided shelter for Ukrainian refugees

Ever since the Russians invaded Ukraine a year ago, refugees have been pouring across the borders of Hungary and other neighbouring countries, seeking shelter and compassion.

The Menedékház Foundation, on the outskirts of Budapest, was in a strong position to deal with the crisis from the very beginning.

Menedékház is a refuge or home for homeless families with children, and for the past 12 years it has been housed in a former army barracks half an hour from the centre of the Hungarian capital.

The head of staff, Ákos Surányi, who showed us around the facilities, says Menedékház was expecting a large number of refugee families and children when the war began, and it was well-placed to deal with the crisis as it began to unfold.

Ákos explains how the foundation has been responding for years to the needs of elderly and disabled people and families who lose their family homes and of homeless people on the streets of Budapest.

Within weeks of the war breaking out last year, Menedékház was coping with the first wave of refugees from Eastern Ukraine. They included both ethnic Ukrainians and Russian-speaking refugees from places like Donbas and Donetsk.

Doctors, nurses, teachers and other professionals volunteered their expertise, and local people donated hampers and food. Grants came from the Bishop’s Refugee Appeal in the Diocese in Europe and USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel), through the efforts of the Revd Dr Frank Hegedus, the priest and chaplain at Saint Margaret’s Anglican Church in Budapest.

Russian-speakers and Ukrainians came together in sharing their compassion for each other, understanding they were all victims of the war.

About 20 families found shelter and accommodation with Menedékház before many of the people in this first group of refugees were able to move on to other countries like Germany, Italy and the UK.

By May, a second group of up to 150 refugees from western Ukraine were being helped by the foundation.

‘No-one expected the war to go on for this long,’ Ákos says. ‘All refugees want to move on, and there are no refugees here now,’ he explains. But they are ready to take more refugee families again.

His optimism is admirable. As he explains, Menedékház is facing imminent closure. The war has also brought spiraling fuel costs and rapidly rising gas, insurance and electricity bills. The war has also played havoc with Hungary’s inflation, and the foundation is facing increasing rent demands and bills that have increased eight-fold.

Despite its success in coping with refugees from Ukraine over the past year, he predicts Menedékház is facing a major financial crisis within weeks, possibly by March. In the face of this uncertainty and possible closure, the centre continues its projects with homeless families and disabled people and with marginalised teenage boys from deprived areas in inner city Budapest.

‘As long as Menedékház continues its work, it has the support of Saint Margaret’s,’ Father Frank says with hope.

(Revd Canon Professor) Patrick Comerford is a former Trustee of USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel) and blogs at www.patrickcomerford.com

Hope springs eternal … a wall painting in the shelter at Menedékház Foundation, Budapest (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

Praying through poems and

with USPG: 7 January 2023

‘Clap quickly your wings, be elated, / Keep swishing, you’re fondly awaited’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

Christmas is not a season of 12 days, despite the popular Christmas song. Christmas is a 40-day season that lasts from Christmas Day (25 December) to Candlemas or the Feast of the Presentation (2 February).

Throughout the 40 days of this Christmas Season, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, Reflecting on a seasonal or appropriate poem;

2, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary, ‘Pray with the World Church.’

oday is Christmas Day in the Calendar of the Ukrainian Orthodox calendar. I arrived in Budapest late on Thursday night and Charlotte and I are spending some days visiting Saint Margaret’s Anglican Church and Father Frank Hegedus with the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel) and the Diocese in Europe to see how the church and church agencies in Hungary are working with refugees from Ukraine.

TMy choice of a seasonal poem this morning is ‘Angel From Heaven’ by Sándor Márai (1900-1989). This is the name of one of the most popular Christmas carols in Hungary and Márai’s poem of the same name was written just after the 1956 revolution, and one of the most popular poems about the 1956 revolution.

After the revolution was crushed by Soviet troops, 200,000 Hungarians fled to the West; those who stayed behind faced arrest or worse, and hundreds were executed. Márai, like many others, was outraged by the brutality of the Soviets, and the inaction of the West.

In its sentimentality, his poem ‘Angel From Heaven’ is not typical of Márai’s work. It is more emotional than most of his poems, and more emotional than much of his writing about World War II.

Sándor Márai was born in 1900 in the Austro-Hungarian town of Kassa, now Košice, the largest city in east Slovakia.

Márai published his first story when he was 15, and he was still a teenager when he experienced world war, epidemic, revolution and exile. He lived in Paris and Berlin and was in Budapest during World War II. When the Communists came to power in 1948, he went into exile in New York. His love for Magyar, the Hungarian language, never wavered, despite his fluency in German..

He reflects on the siege of Budapest in 1944, when the Russians and Germans fought over the capital and 35,000 civilians died, in his Book of Verses.

In his writing he chides his fellow Hungarian for not resisting the Nazis more forcefully, but he also borders on antisemitism when he deplores those Jews he sees as working as thugs for the Communists.

Funeral Oration is considered Márai’s poetic masterpiece. His appropriation of the earliest literary text in Hungarian, dating from the 12th century, is Márai’s attempt to underpin the place of Hungarian literature. He cites his country’s great creative figures, including the composer Bartók, the painter Rippl-Rónai, and the writers Arany, Babits and Krúdy.

Márai died by suicide in San Diego at the age of 88 on 22 February 1989. His ashes were scattered in the Pacific.

‘Angel from Heaven, do rush, don’t rest, / Hurry to smouldering Budapest’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Angel from heaven (translated by Leslie A Kery)

Angel from Heaven, do rush, don’t rest,

Hurry to smouldering Budapest.

Go to where, among the Russian tanks,

The silent bells give no sound of thanks.

Where there’s no Christmas sparkle to please,

Where nuts painted gold don't hang on trees,

There’s nothing but hunger, shivers, cold,

Do speak so they will grasp what you told.

Split with your voice the night asunder:

Angel, carry news of the wonder:

Clap quickly your wings, be elated,

Keep swishing, you’re fondly awaited.

Don’t speak of the world from whence you came,

Where candles are burning, bright the flame,

Tables are spread, the houses have heat,

Priests with their fine words console, entreat,

Crinkling of paper, gifts given, sent,

Wise words to ponder, clever intent.

Sparklers are sparkling upon the trees:

Angel, do speak of the wonder please!

This is world wonder, relate, explain:

A poor people’s tree had burst into flame;

A Christmas tree in the Silent Night,

And many cross themselves at the sight.

It’s watched by the folk of continents,

Some grasp it, for some it makes no sense.

Far too much for some to hold at bay.

They’re shaking their heads, they shudder, pray,

For those aren’t sweets that hang on the tree:

’Tis Christ of the people: Hungary.

And many pass by and some advance:

The soldier, who pierced him with a lance,

The Pharisee, who sold him for a price,

Then one, who when asked, denied him thrice,

One, whose hand had shared the bowl with Him,

Who for silver coins had offered Him,

And whilst abusing, wielded the lash,

Had drank his blood and he ate his flesh –

The crowd is standing around, they stare,

But to address Him there’s none to dare.

Silent victim, no accusal tried,

Just watches like Christ did crucified.

Strange tree of Christmas, who brought this tree,

Devil or Angel, who could it be,

Those, who for his robe are tossing dice,

Know not what they do, know not the price,

Just sniff and yelp, want to bring to light

The mystery, the secret of this night,

Strange is this Christmas, strange things are these:

The Magyar Nation hangs on the trees.

The world talks wonder, to that they’re glued,

Priests drone of gumption and fortitude.

Statesmen produce farewell addresses,

His Holiness then duly blesses.

All kinds of people, all ranks – a sea –,

Question why all of this had to be.

Not perished as asked – can’t comprehend.

Why not in silence await the end?

Why had the skies turned from fair to rough?

Because a people had cried ‘Enough!’

Many can’t grasp it, though they had tried,

What rose up here like an ocean tide?

Why was world order shaking and strained?

A nation cried out. Then silence reigned.

Many are asking: what was the cause?

Who made from bones and the flesh the laws?

More and more ask it, there seems no end

Haltingly, for they can’t comprehend –

Those, for whom Freedom bequest had brought,

Ask it: is Freedom so great a thought?

Angel, bring down the word from the skies:

New life from blood will always arise.

Quite a few times and even some more,

Child met donkey and shepherd before,

If by the manger, on littered earth,

One life had given another birth,

‘Tis they who’ll mind that wonder and will

Stand with breath bated as sentry still,

For bright the star is, dawn breaks as well:

Angel from heaven … tell them, do tell.

‘For bright the star is, dawn breaks as well: / Angel from heaven … tell them, do tell’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

USPG Prayer Diary:

The theme in the USPG Prayer Diary this week is ‘Refugee Response in Finland.’ This theme was introduced on Sunday by the Revd Tuomas Mäkipää, Chaplain at Saint Nicholas’ Anglican Church in Helsinki, who tells how a USPG grant is helping to support Ukrainian refugees.

The USPG Prayer Diary invites us to pray today in these words:

Let us give thanks for Saint Nicholas’ Chaplaincy and its work with refugees. May our support for those displaced by war never grow weary.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

‘One … Who for silver coins had offered Him’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

Christmas is not a season of 12 days, despite the popular Christmas song. Christmas is a 40-day season that lasts from Christmas Day (25 December) to Candlemas or the Feast of the Presentation (2 February).

Throughout the 40 days of this Christmas Season, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, Reflecting on a seasonal or appropriate poem;

2, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary, ‘Pray with the World Church.’

oday is Christmas Day in the Calendar of the Ukrainian Orthodox calendar. I arrived in Budapest late on Thursday night and Charlotte and I are spending some days visiting Saint Margaret’s Anglican Church and Father Frank Hegedus with the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel) and the Diocese in Europe to see how the church and church agencies in Hungary are working with refugees from Ukraine.

TMy choice of a seasonal poem this morning is ‘Angel From Heaven’ by Sándor Márai (1900-1989). This is the name of one of the most popular Christmas carols in Hungary and Márai’s poem of the same name was written just after the 1956 revolution, and one of the most popular poems about the 1956 revolution.

After the revolution was crushed by Soviet troops, 200,000 Hungarians fled to the West; those who stayed behind faced arrest or worse, and hundreds were executed. Márai, like many others, was outraged by the brutality of the Soviets, and the inaction of the West.

In its sentimentality, his poem ‘Angel From Heaven’ is not typical of Márai’s work. It is more emotional than most of his poems, and more emotional than much of his writing about World War II.

Sándor Márai was born in 1900 in the Austro-Hungarian town of Kassa, now Košice, the largest city in east Slovakia.

Márai published his first story when he was 15, and he was still a teenager when he experienced world war, epidemic, revolution and exile. He lived in Paris and Berlin and was in Budapest during World War II. When the Communists came to power in 1948, he went into exile in New York. His love for Magyar, the Hungarian language, never wavered, despite his fluency in German..

He reflects on the siege of Budapest in 1944, when the Russians and Germans fought over the capital and 35,000 civilians died, in his Book of Verses.

In his writing he chides his fellow Hungarian for not resisting the Nazis more forcefully, but he also borders on antisemitism when he deplores those Jews he sees as working as thugs for the Communists.

Funeral Oration is considered Márai’s poetic masterpiece. His appropriation of the earliest literary text in Hungarian, dating from the 12th century, is Márai’s attempt to underpin the place of Hungarian literature. He cites his country’s great creative figures, including the composer Bartók, the painter Rippl-Rónai, and the writers Arany, Babits and Krúdy.

Márai died by suicide in San Diego at the age of 88 on 22 February 1989. His ashes were scattered in the Pacific.

‘Angel from Heaven, do rush, don’t rest, / Hurry to smouldering Budapest’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Angel from heaven (translated by Leslie A Kery)

Angel from Heaven, do rush, don’t rest,

Hurry to smouldering Budapest.

Go to where, among the Russian tanks,

The silent bells give no sound of thanks.

Where there’s no Christmas sparkle to please,

Where nuts painted gold don't hang on trees,

There’s nothing but hunger, shivers, cold,

Do speak so they will grasp what you told.

Split with your voice the night asunder:

Angel, carry news of the wonder:

Clap quickly your wings, be elated,

Keep swishing, you’re fondly awaited.

Don’t speak of the world from whence you came,

Where candles are burning, bright the flame,

Tables are spread, the houses have heat,

Priests with their fine words console, entreat,

Crinkling of paper, gifts given, sent,

Wise words to ponder, clever intent.

Sparklers are sparkling upon the trees:

Angel, do speak of the wonder please!

This is world wonder, relate, explain:

A poor people’s tree had burst into flame;

A Christmas tree in the Silent Night,

And many cross themselves at the sight.

It’s watched by the folk of continents,

Some grasp it, for some it makes no sense.

Far too much for some to hold at bay.

They’re shaking their heads, they shudder, pray,

For those aren’t sweets that hang on the tree:

’Tis Christ of the people: Hungary.

And many pass by and some advance:

The soldier, who pierced him with a lance,

The Pharisee, who sold him for a price,

Then one, who when asked, denied him thrice,

One, whose hand had shared the bowl with Him,

Who for silver coins had offered Him,

And whilst abusing, wielded the lash,

Had drank his blood and he ate his flesh –

The crowd is standing around, they stare,

But to address Him there’s none to dare.

Silent victim, no accusal tried,

Just watches like Christ did crucified.

Strange tree of Christmas, who brought this tree,

Devil or Angel, who could it be,

Those, who for his robe are tossing dice,

Know not what they do, know not the price,

Just sniff and yelp, want to bring to light

The mystery, the secret of this night,

Strange is this Christmas, strange things are these:

The Magyar Nation hangs on the trees.

The world talks wonder, to that they’re glued,

Priests drone of gumption and fortitude.

Statesmen produce farewell addresses,

His Holiness then duly blesses.

All kinds of people, all ranks – a sea –,

Question why all of this had to be.

Not perished as asked – can’t comprehend.

Why not in silence await the end?

Why had the skies turned from fair to rough?

Because a people had cried ‘Enough!’

Many can’t grasp it, though they had tried,

What rose up here like an ocean tide?

Why was world order shaking and strained?

A nation cried out. Then silence reigned.

Many are asking: what was the cause?

Who made from bones and the flesh the laws?

More and more ask it, there seems no end

Haltingly, for they can’t comprehend –

Those, for whom Freedom bequest had brought,

Ask it: is Freedom so great a thought?

Angel, bring down the word from the skies:

New life from blood will always arise.

Quite a few times and even some more,

Child met donkey and shepherd before,

If by the manger, on littered earth,

One life had given another birth,

‘Tis they who’ll mind that wonder and will

Stand with breath bated as sentry still,

For bright the star is, dawn breaks as well:

Angel from heaven … tell them, do tell.

‘For bright the star is, dawn breaks as well: / Angel from heaven … tell them, do tell’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

USPG Prayer Diary:

The theme in the USPG Prayer Diary this week is ‘Refugee Response in Finland.’ This theme was introduced on Sunday by the Revd Tuomas Mäkipää, Chaplain at Saint Nicholas’ Anglican Church in Helsinki, who tells how a USPG grant is helping to support Ukrainian refugees.

The USPG Prayer Diary invites us to pray today in these words:

Let us give thanks for Saint Nicholas’ Chaplaincy and its work with refugees. May our support for those displaced by war never grow weary.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

‘One … Who for silver coins had offered Him’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)