The Roman Theatre at Verulamium is said to be the only full excavated example of its kind in England (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2024)

Patrick Comerford

During my visits to St Albans over the past week or two, I found myself walking in, out and through sites that are part of the Roman city of Verulamium.

The major ancient Roman route Watling Street passed through the city and Verulamium was the first major town for travellers heading north. Saint Alban, the first martyr in England, was executed in Verulamium during a Roman persecution of Christians in the third or fourth century.

Verulamium was located south-west of the present cathedral city of St Albans in Hertfordshire. A large part of the Roman city has still not been excavated, and is now lies beneath park and agricultural land.

Over the centuries, ploughing on the privately owned agricultural land has done much damage to the site. Parts of mosaic floors have been found on the surface, and ground penetrating radar studies show the outlines of buildings as smudges rather than clearly defined walls like those protected by the parkland.

Saint Alban may have been taken across the River Ver at Saint Michael’s to his execution on the site of St Albans Abbey (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2024)

Part of the Roman city has been built on, and Saint Michael’s Church, which I described on Sunday afternoon, was built in the 10th century on the site of the basilica, the headquarters of Roman Verulamium. Saint Alban may have been tried there before he was taken across the River Ver and executed on a hill outside the town walls, perhaps on the site of St Albans Abbey and the present cathedral.

Other parts of the Roman town were built on during the Middle Ages, but much of the site and its environs are now classified as a scheduled monument.

Before the Romans established their settlement at Verulamium, the area was already the location of a tribal centre belonging to the Catuvellauni, a Celtic people linked to Belgic Gaul. This settlement is usually called Verlamion.

The etymology is uncertain, but the name has been reconstructed as Uerulāmion, meaning ‘the tribe or settlement of the broad hand’ (Uerulāmos). In this pre-Roman form, it was among the first places in Britain recorded by name. The settlement was established ca 20 BCE by Tasciovanus, who minted coins there and died in the year 9 CE.

The Roman settlement of Verulamium was granted the status of municipium around 50 CE, giving its citizens ‘Latin Rights’, a lesser citizenship status than those of a colonia.

It grew to a significant town, and Verulamium was sacked and burnt on the orders of Queen Boudica of the Iceni in 61 CE. A black ash layer has been recorded by archaeologists, confirming the Roman written record.

Verulamium is mentioned in a Latin inscription on a wax tablet, dated to 62 CE, discovered in London during the Bloomberg excavations in 2010-2014.

The rebuilt town grew steadily. By the early third century, it covered an area of about 0.5 sq km (125 acres), behind a deep ditch and wall.

Part of the Roman walls in Verulamium, with St Albans Cathedral on the hill above (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2024)

Verulamium had a forum, basilica and a theatre, much of which were damaged during two fires, one in the year 155 and the other ca 250. One of the few extant Roman inscriptions in Britain is found on the remnants of the forum.

The town was rebuilt in stone rather than timber at least twice over the next 150 years. The occupation by the Romans ended between 400 and 450 CE.

Few remains of the Roman city are visible today, but they include parts of the city walls, a hypocaust still at its original location under a mosaic floor, and the theatre, as well as items in the Museum.

The hypocaust, located within Verulamium Park, was an ancient underfloor heating system that was a marvel of Roman engineering and an example of the first indoor heating systems in Britain.

Roman hypocaust systems allowed hot air to circulate beneath the floor and through the walls of buildings. Floors were raised on brick columns or, as in this case, trenches were cut below the floor to allow the hot air through. The mosaic covering the hypocaust was made of tesserae or small cubes of cut stone or tile, set into a thin layer of fine mortar that was spread over a concrete floor.

The floor is thought to have been part of the reception and meeting rooms of a large town house, built ca 200 CE near Watling Street. The hypocaust was uncovered during excavations in Verulamium Park in the 1930s by Sir Mortimer and Tessa Wheeler. It was decided that it would be best to leave both the mosaic and hypocaust in their original Roman location and today they are on view in modern building open to visitors.

More remains under agricultural land nearby have never been excavated and for a while were seriously threatened by deep ploughing. Recent results of GPR (ground penetrating radar) studies have revealed more damage has been done to most buildings than originally thought, especially in the north-west part of the old Roman city.

The Roman theatre at Verulamium is said to be the only full excavated example of its kind in Britain. This was a theatre with a stage rather than an amphitheatre, and it stands within the grounds of the Gorhambury Estate.

By the eighth century, the Saxon inhabitants of St Albans were aware of their older Roman neighbour, which they knew alternatively as Verulamacæstir or Vaeclingscæstir, ‘the fortress of the followers of Wæcla.’

The city was quarried for building material to build mediaeval St Albans Abbey. Much of the Norman abbey was built from the remains of the Roman city, with Roman brick and stone visible.

St Albans Abbey, now St Albans Cathedral, is near the site of a Roman cemetery outside the city walls. It is not known whether there are Roman remains under the mediaeval abbey, and an archaeological excavation in 1978 did not find any Roman remains on the site of the mediaeval chapter house.

The Verulamium Museum, part of St Albans Museums, is in Verulamium Park, beside Saint Michael’s Church and the site of the Roman basilica. It was established following the excavations in the 1930s by Sir Mortimer Wheeler and Tessa Wheeler. The exhibits include large and colourful mosaics and many other artefacts, such as pottery, jewellery, tools and coins from the Roman period. Many were found in formal excavations, but some, including a coffin with a male skeleton, were unearthed nearby during building work.

Since much of the modern city and its environs are built over Roman remains, it is still common to unearth Roman artefacts several miles away. A complete tile kiln was found in Park Street almost 10 km (6 miles) from Verulamium, and there is a Roman mausoleum 8 km (5 miles) away, near Rothamsted Park .

The excavations at the Roman Theatre of Verulamium with Saint Michael’s Church and the site of the Roman basilica in the background (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2024)

23 January 2024

Daily prayers during

Christmas and Epiphany:

30, 23 January 2024

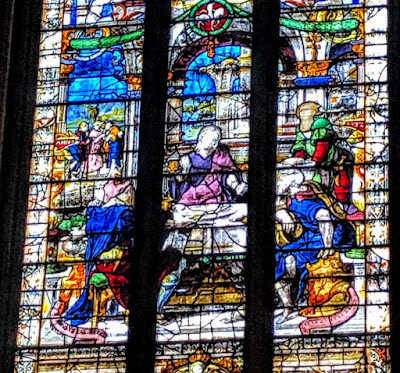

Christ in the home of Mary, Martha and Lazarus … a panel in the Herkenrode glass windows in the Lady Chapel in Lichfield Cathedral (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

The celebrations of Epiphany-tide continue today, and the week began with the Third Sunday of Epiphany (21 January 2024). Today is also the sixth day of the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity.

Christmas is a season that lasts for 40 days that continues from Christmas Day (25 December) to Candlemas or the Feast of the Presentation (2 February) The Gospel reading on Sunday (John 2: 1-11) told of the Wedding at Cana, one of the traditional Epiphany stories.

In keeping with the theme of Sunday’s Gospel reading, my reflections each morning throughout the seven days of this week include:

1, A reflection on one of seven meals Jesus has with family, friends or disciples;

2, the Gospel reading of the day;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

The East Window in Saint Peter and Saint Paul Church, Watford, Northamptonshire, shows Christ in the home of Mary and Martha (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

3, The meal with Mary and Martha (Luke 10: 38-42):

Saint Luke’s story of the meal that Jesus has with his friends Mary and Martha is not found in the other synoptic gospels, and the only other parallel is in the Fourth Gospel, where Jesus visits Mary and Martha after the death of Lazarus.

So the meals Jesus has with Mary and Martha must be understood in the light of the Resurrection, which is prefigured by the raising of Lazarus from the dead.

For many women, and for many men too, the story of the meal with Martha and Mary raises many problems, often created by the agenda with which we now approach this story, but an agenda that may not have been possible to imagine when Saint Luke’s Gospel was written.

Our approach to understanding and explaining this meal very often depends on the way in which I understand Martha and the busy round of activities that have her distracted, and that cause her to complain to Jesus about her sister’s apparent lack of zeal and activity.

These activities in the Greek are described as Martha’s service – she is the deacon at the table: where the NRSV says ‘But Martha was distracted by her many tasks,’ the Greek says: ἡ δὲ Μάρθα περιεσπᾶτο περὶ πολλὴν διακονίαν (But Martha was being distracted by much diaconal work, service at the table).

Quite often, when this story is told, over and over, again and again, it is told as if Martha is getting stroppy about having to empty the dishwasher while Mary is lazing, sitting around, chattering with Jesus.

Does Martha see that Mary should only engage in kitchen work too?

Does she think, perhaps, that only Lazarus should be out at the front of the house, keeping Jesus engaged in lads’ banter about the latest match between Bethany United and Jerusalem City?

Is Jesus being too dismissive of Martha’s complaints?

Or is he defending Mary’s right to engage in a full discussion of the Word, to engage in an alive ministry of the Word?

Martha is presented in this story as the dominant, leading figure. It is she who takes the initiative and who welcomes Jesus into her home (verse 38). It is she who offers the hospitality, who is the host at the meal, who is the head of the household – in fact, Lazarus isn’t even on the stage for this scene, and Mary is merely ‘her sister’ – very much the junior partner in the household.

Yet it is Mary, the figure on the margins, who offers the sort of hospitality that Jesus commends and praises.

Mary simply listens to Jesus, sitting at his feet, like a student would sit at the feet of a great rabbi or teacher, waiting and willing to learn what is being taught.

Martha is upset about this, and comes out from the back and asks Jesus to pack off Mary to the kitchen where she can help Martha.

But perhaps Martha was being too busy with her household tasks.

I was once invited to dinner by people I knew as good friends. And for a long time I was left on my own with the other guest as the couple busied themselves with things in the kitchen – they had decided to do the washing up before bringing out the coffee … the wife knew that if she left the washing up until later, the husband would shirk his share of the task.

But being left on our own was a little embarrassing. Part of the joy of being invited to someone’s home for dinner is the conversation around the table.

When I have been on retreats, at times, in Greek Orthodox monasteries, conversation at the table has been discouraged by a monk reading, usually from the writings of the Early Fathers, from the Patristic writings.

But a good meal, good table fellowship, good hospitality is not just about the food that is served, but about the conversation around the table too.

One commentator suggests that Martha has gone overboard in her duties of hospitality. She has spent too much time preparing the food, and has failed to pay real attention to her guest.

On the other hand, Mary has chosen her activity (verse 42). It does not just happen by accident. Mary has chosen to offer Jesus the real hospitality that a guest should be offered. She talks to Jesus, and real conversation is about both talking and listening.

If she is sent back into the kitchen, then – in the absence of Lazarus, indeed, in the notable absence of the disciples – Jesus would be left without hospitality, without words of welcome, without conversation.

Perhaps Martha might have been better off if she had a more simple lifestyle, if she had prepared just one dish for her guest and for her family – might I be bold enough to suggest, if she had been content for them to sup on bread and wine alone.

She could have joined Mary in her hospitality, in welcoming Jesus to their home and to their table; they could have been in full communion with one another.

In this way, Martha will experience what her sister is experiencing, but which she is too busy to notice – their visitor’s invitation into the hospitality of God.

One commentator, Brendan Byrne, points out the subtle point being made in this story:

‘Frenetic service, even service of the Lord, can be a deceptive distraction from what the Lord really wants. Luke has already warned that the grasp of the word can be choked by the cares and worries of life … Here the cares and worries seem well justified – are they not in the service of the Lord? But precisely therein lies the power of the temptation, the great deceit. True hospitality – even that given directly to the Lord – attends to what the guest really wants.’

Christ in the House of Martha and Mary by Diego Velázquez (1630)

Christ in the House of Martha and Mary by Diego Velázquez (1630)

Mark 3: 31-35 (NRSVA):

31 Then his mother and his brothers came; and standing outside, they sent to him and called him. 32 A crowd was sitting around him; and they said to him, ‘Your mother and your brothers and sisters are outside, asking for you.’ 33 And he replied, ‘Who are my mother and my brothers?’ 34 And looking at those who sat around him, he said, ‘Here are my mother and my brothers! 35 Whoever does the will of God is my brother and sister and mother.’

‘Christ at the home of Martha and Mary,’ Georg Friedrich Stettner (1639)

Today’s Prayers (Tuesday 23 January 2024):

The theme this week in ‘Pray With the World Church,’ the Prayer Diary of the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel), is: ‘Provincial Programme on Capacity Building in Paraná.’ This theme was introduced on Sunday by Christina Takatsu Winnischofer, Igreja Episcopal Anglicana do Brasil.

The USPG Prayer Diary today (23 January 2024) invites us to pray in these words:

Heavenly Father, we pray for all the clergy and laity in the Province of Brazil. May You strengthen them in will, knowledge and health so that they can reach out to their communities.

The Collect:

Almighty God,

whose Son revealed in signs and miracles

the wonder of your saving presence:

renew your people with your heavenly grace,

and in all our weakness

sustain us by your mighty power;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

The Post-Communion Prayer:

Almighty Father,

whose Son our Saviour Jesus Christ is the light of the world:

may your people,

illumined by your word and sacraments,

shine with the radiance of his glory,

that he may be known, worshipped, and obeyed

to the ends of the earth;

for he is alive and reigns, now and for ever.

Additional Collect:

God of all mercy,

your Son proclaimed good news to the poor,

release to the captives,

and freedom to the oppressed:

anoint us with your Holy Spirit

and set all your people free

to praise you in Christ our Lord.

Yesterday’s reflection (The Feeding of the Multitude)

Continued tomorrow (The meal with Zacchaeus)

The Risen Christ with Mary of Bethany (left) and Mary Magdalene (right) … a stained glass window in Saint Nicholas’s Church, Adare, Co Limerick (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Patrick Comerford

The celebrations of Epiphany-tide continue today, and the week began with the Third Sunday of Epiphany (21 January 2024). Today is also the sixth day of the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity.

Christmas is a season that lasts for 40 days that continues from Christmas Day (25 December) to Candlemas or the Feast of the Presentation (2 February) The Gospel reading on Sunday (John 2: 1-11) told of the Wedding at Cana, one of the traditional Epiphany stories.

In keeping with the theme of Sunday’s Gospel reading, my reflections each morning throughout the seven days of this week include:

1, A reflection on one of seven meals Jesus has with family, friends or disciples;

2, the Gospel reading of the day;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

The East Window in Saint Peter and Saint Paul Church, Watford, Northamptonshire, shows Christ in the home of Mary and Martha (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

3, The meal with Mary and Martha (Luke 10: 38-42):

Saint Luke’s story of the meal that Jesus has with his friends Mary and Martha is not found in the other synoptic gospels, and the only other parallel is in the Fourth Gospel, where Jesus visits Mary and Martha after the death of Lazarus.

So the meals Jesus has with Mary and Martha must be understood in the light of the Resurrection, which is prefigured by the raising of Lazarus from the dead.

For many women, and for many men too, the story of the meal with Martha and Mary raises many problems, often created by the agenda with which we now approach this story, but an agenda that may not have been possible to imagine when Saint Luke’s Gospel was written.

Our approach to understanding and explaining this meal very often depends on the way in which I understand Martha and the busy round of activities that have her distracted, and that cause her to complain to Jesus about her sister’s apparent lack of zeal and activity.

These activities in the Greek are described as Martha’s service – she is the deacon at the table: where the NRSV says ‘But Martha was distracted by her many tasks,’ the Greek says: ἡ δὲ Μάρθα περιεσπᾶτο περὶ πολλὴν διακονίαν (But Martha was being distracted by much diaconal work, service at the table).

Quite often, when this story is told, over and over, again and again, it is told as if Martha is getting stroppy about having to empty the dishwasher while Mary is lazing, sitting around, chattering with Jesus.

Does Martha see that Mary should only engage in kitchen work too?

Does she think, perhaps, that only Lazarus should be out at the front of the house, keeping Jesus engaged in lads’ banter about the latest match between Bethany United and Jerusalem City?

Is Jesus being too dismissive of Martha’s complaints?

Or is he defending Mary’s right to engage in a full discussion of the Word, to engage in an alive ministry of the Word?

Martha is presented in this story as the dominant, leading figure. It is she who takes the initiative and who welcomes Jesus into her home (verse 38). It is she who offers the hospitality, who is the host at the meal, who is the head of the household – in fact, Lazarus isn’t even on the stage for this scene, and Mary is merely ‘her sister’ – very much the junior partner in the household.

Yet it is Mary, the figure on the margins, who offers the sort of hospitality that Jesus commends and praises.

Mary simply listens to Jesus, sitting at his feet, like a student would sit at the feet of a great rabbi or teacher, waiting and willing to learn what is being taught.

Martha is upset about this, and comes out from the back and asks Jesus to pack off Mary to the kitchen where she can help Martha.

But perhaps Martha was being too busy with her household tasks.

I was once invited to dinner by people I knew as good friends. And for a long time I was left on my own with the other guest as the couple busied themselves with things in the kitchen – they had decided to do the washing up before bringing out the coffee … the wife knew that if she left the washing up until later, the husband would shirk his share of the task.

But being left on our own was a little embarrassing. Part of the joy of being invited to someone’s home for dinner is the conversation around the table.

When I have been on retreats, at times, in Greek Orthodox monasteries, conversation at the table has been discouraged by a monk reading, usually from the writings of the Early Fathers, from the Patristic writings.

But a good meal, good table fellowship, good hospitality is not just about the food that is served, but about the conversation around the table too.

One commentator suggests that Martha has gone overboard in her duties of hospitality. She has spent too much time preparing the food, and has failed to pay real attention to her guest.

On the other hand, Mary has chosen her activity (verse 42). It does not just happen by accident. Mary has chosen to offer Jesus the real hospitality that a guest should be offered. She talks to Jesus, and real conversation is about both talking and listening.

If she is sent back into the kitchen, then – in the absence of Lazarus, indeed, in the notable absence of the disciples – Jesus would be left without hospitality, without words of welcome, without conversation.

Perhaps Martha might have been better off if she had a more simple lifestyle, if she had prepared just one dish for her guest and for her family – might I be bold enough to suggest, if she had been content for them to sup on bread and wine alone.

She could have joined Mary in her hospitality, in welcoming Jesus to their home and to their table; they could have been in full communion with one another.

In this way, Martha will experience what her sister is experiencing, but which she is too busy to notice – their visitor’s invitation into the hospitality of God.

One commentator, Brendan Byrne, points out the subtle point being made in this story:

‘Frenetic service, even service of the Lord, can be a deceptive distraction from what the Lord really wants. Luke has already warned that the grasp of the word can be choked by the cares and worries of life … Here the cares and worries seem well justified – are they not in the service of the Lord? But precisely therein lies the power of the temptation, the great deceit. True hospitality – even that given directly to the Lord – attends to what the guest really wants.’

Christ in the House of Martha and Mary by Diego Velázquez (1630)

Christ in the House of Martha and Mary by Diego Velázquez (1630)Mark 3: 31-35 (NRSVA):

31 Then his mother and his brothers came; and standing outside, they sent to him and called him. 32 A crowd was sitting around him; and they said to him, ‘Your mother and your brothers and sisters are outside, asking for you.’ 33 And he replied, ‘Who are my mother and my brothers?’ 34 And looking at those who sat around him, he said, ‘Here are my mother and my brothers! 35 Whoever does the will of God is my brother and sister and mother.’

‘Christ at the home of Martha and Mary,’ Georg Friedrich Stettner (1639)

Today’s Prayers (Tuesday 23 January 2024):

The theme this week in ‘Pray With the World Church,’ the Prayer Diary of the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel), is: ‘Provincial Programme on Capacity Building in Paraná.’ This theme was introduced on Sunday by Christina Takatsu Winnischofer, Igreja Episcopal Anglicana do Brasil.

The USPG Prayer Diary today (23 January 2024) invites us to pray in these words:

Heavenly Father, we pray for all the clergy and laity in the Province of Brazil. May You strengthen them in will, knowledge and health so that they can reach out to their communities.

The Collect:

Almighty God,

whose Son revealed in signs and miracles

the wonder of your saving presence:

renew your people with your heavenly grace,

and in all our weakness

sustain us by your mighty power;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

The Post-Communion Prayer:

Almighty Father,

whose Son our Saviour Jesus Christ is the light of the world:

may your people,

illumined by your word and sacraments,

shine with the radiance of his glory,

that he may be known, worshipped, and obeyed

to the ends of the earth;

for he is alive and reigns, now and for ever.

Additional Collect:

God of all mercy,

your Son proclaimed good news to the poor,

release to the captives,

and freedom to the oppressed:

anoint us with your Holy Spirit

and set all your people free

to praise you in Christ our Lord.

Yesterday’s reflection (The Feeding of the Multitude)

Continued tomorrow (The meal with Zacchaeus)

The Risen Christ with Mary of Bethany (left) and Mary Magdalene (right) … a stained glass window in Saint Nicholas’s Church, Adare, Co Limerick (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)