Visiting Comberford Hall, between Lichfield and Tamworth, in rural Staffordshire

2025:

‘Diversity in Sarawak’, pp 20-21 in

Pray with the World Church: Prayers And Reflections from The Anglican Communion, 1 June 2025 – 29 November 2025 (London: USPG, 2025, 64 pp)

Book review:

Church Going: A Stonemason’s Guide to the Churches of the British Isles, by Andrew Ziminski (London, Profile Books, 2024), in the

Irish Theological Quarterly (Maynooth), Volume 90 Issue 2, April 2025, pp 239-240.

Nine photographs (pp 7, 26, 36, 38, 38, 46, 47, 49, 49) in

Co. Clare Visitor Guide, ed Sally Davies (Smarttraveller365, 2025), 64 pp.

One photograph (p 42) in

County Kerry Visitor Guide, ed Sally Davies (Smarttraveller365, 2025), 76 pp.

Photograph of Saint Peter's Church, Kuching, in

Herald Malaysia (1 July 2025).

2024:

Προλογος / Foreword, pp 5-8 in Panos Karagiorgos,

Ελληνικα Δημοτικα Τραγουδια,

Greek Folk Songs (Thessaloniki, Εκδοτικος Οικος Κ & Μ Σταμουλη, 2024, 203 pp ISBN: 978-960-656-200-6).

‘The Lamport Crucifix’, in: Catriona Finlayson (ed),

50 Years of the Lamport Hall Preservation Trust (Lamport, Northamptonshire, 2024, 100 pp), pp 54-57, with photographs

‘Bourke’s House’, in: Denis O’Shaughnessy (ed),

The Story of Athlunkard Street, 1824-2024 (Limerick, 2024, 206 pp), pp 10-13.

‘Foreword’ (pp iv-v) and photograph (p 181) in: Rod Smith,

Clancarty – the high times and humble of a noble Irish family (Tauranga, New Zealand: Eyeglass Press, 2024, xviii + 341 pp, ISBN 978-0-473-70863-4)

Patrick Comerford and Sarah Friedman,

Milton Keynes & District Reform Synagogue: an introduction (6 pp pamphlet, with six photographs, Milton Keynes, 17 November 2024)

‘Did St Patrick Bring Christianity to Ireland’,

Conversations (Dublin: Dominican Publications, ed Bernard Treacy), Vol 1 No 2, March/April 2024, pp 77-80, ISSN 2990-8388.

Book Review:

Towards a Theology of Liturgy: A Collection of Essays on West Syrian Liturgical Theology, Fr Dr KM Koshy Vaidyan, Kottayam: Mashikkoottu, 2023, 232 pp, ISBN 978-81-966011-5-7, in

The Journal of Malankara Orthodox Theological Studies (Orthodox Theological Seminary, Kerala, India), Vol viii No 2 (July-December 2023), pp 113-115 (published February 2024).

‘Richard Rawle, the Vicar of Tamworth who became a Bishop in Trinidad’,

Tamworth Heritage Magazine, Vol 2 No 1, Winter 2024 (January 2024), ed Chris Hills (ISSN 2753-4162 9772 7534 16209), pp 11-14 (with photographs)

‘William Wailes, stained glass artist’,

Tamworth Heritage Magazine, Vol 2 No 1, Winter 2024 (January 2024), ed Chris Hills (ISSN 2753-4162 9772 7534 16209), pp 17-18 (with four photographs)

Photograph, ‘Forgiveness and love in the face of death and mass murder … a fading rose on the fence at Birkenau’, p 202 in Frank Callery,

Ceangailte Tied Appendixes of Pain (Kilkenny: O’Mega Publications), 250 pp, forthcoming poetry collection

Photograph (Bryce House, February 2025) in ‘Garnish Island Calendar 2025’ (produced by Deirdre Goyvaerts for Scoil Fhiachna National School, Glengarriff, Co Cork, 2024)

Photograph, ‘The Liberties College’, illustrating

feature by Mary Phelan in

The Liberty (local newspaper, Dublin), 2 November 2024.

2023:

‘The Sephardic family roots and heritage of John Desmond Bernal, Limerick scientist’, pp 60-66 in

The Old Limerick Journal, ed Tom Donovan (Limerick: Limerick Museum, ISBN: 9781916294394, 72 pp), No 58, Winter 2023, with nine photographs, 1 December 2023.

‘Church-goers in Limerick During War and Revolution’, Chapter 6, pp 83-89, in

Histories of Protestant Limerick, 1912-1923, ed Seán William Gannon and Brian Hughes (Limerick: Limerick City & County Council, 2023, ISBN 978-1-999-6911-6, 132 pp); with three photographs, pp 70-71.

‘The ‘Wexford Carol’ and the mystery surrounding some old and popular Christmas carols’, pp 72-77 in

Christmas and the Irish: a miscellany, ed Salvador Ryan (Dublin: Wordwell Books, 2023, ISBN: 978-1-913934-93-4, 403 pp, €25), with photograph on p 71.

‘Molly Bloom’s Christmas Card: where Joycean fiction meets a real-life family’ is published in

Christmas and the Irish: a miscellany, ed Salvador Ryan (Dublin: Wordwell Books, 2023, ISBN: 978-1-913934-93-4, 403 pp, €25), pp 151-155, including a photograph on p 155.

‘‘We Three Kings of Orient are’: an Epiphany carol with Irish links’, pp 103-107 in

Christmas and the Irish: a miscellany, ed Salvador Ryan (Dublin: Wordwell Books, 2023, ISBN: 978-1-913934-93-4, 403 pp, €25).

<< Ο Sir Richard Church και οι Ιρλανδοι Φιλελληνες στον Πολεμο των Ελληνων για την Ανεξαρτησια >>, pp 53-75, in Πανος Καραγιώργος και Patrick Comerford,

Ο Φιλελληνισμος και η Ελληνικη Επανασταση του 1821 (Θεσσαλονικη: Εκδοτικος Οικος Κ κ Σταμουλη, 2023, 78 pp), ISBN: 978-960-656-115-9.

Who is Our Neighbour? (London: USPG, 2023, ISBN: 2631-4995, 48 pp), editor and Introduction, pp 5-6; a six-session study course for Lent 2023.

Daily reading (26 March 2023), ‘Mercy: Be merciful … do not judge …’, Christian Aid online resources

Photograph (p 137) in: Jack Kavanagh,

Always Ireland, An Insider’s Tour of the Emerald Isle (Washington DC: National Geographic, 2023), 336 pp, hb, ISBN 978-1-4262-2216-0, $35 in the US (March 2023).

Cover photograph: Tim Vivian,

A Doorway into Thanks: Further Reflections on Scripture (Austin Macauley Publishers, London, Cambridge, New York, Sharjah), ISBN: 9781685620004, $14.95 in the US (April 2023)

Three photographs (pp 78, 165, 355) in: Hellgard Leckebusch,

Singing our Song, the Memoirs of Hellgard Leckebusch (1944-2023), eds, Silke Püttmann and Kenneth Ferguson (Mettmann, NRW, Germany: Silke Püttmann, May 2023, e-book).

2022:

‘Barbara Heck and Philip Embury: Founders of American Methodism’, pp 109-111, in David Bracken, ed,

Of Limerick Saints and Sinners (Dublin: Veritas, 2022, ISBN: 9781800970311), 266 pp.

‘Mother Mary Whitty: Sign of the Cross in Korea’, pp 213-215, in David Bracken, ed,

Of Limerick Saints and Sinners (Dublin: Veritas, 2022, ISBN: 9781800970311, 266 pp).

‘Lichfield’s Hidden Writers’ (with Jono Oates),

CityLife in Lichfield, August 2022, p 34.

‘For the Life of the World: Toward a Social Ethos of the Orthodox Church’

Studies in Christian Ethics, 35 (2), May 2022 (SAGE: Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC, Melbourne, ISBN 0953-9468), pp 342-359.

‘Saint Patrick: the myths, the legends and his relevance to Ireland today,’

Reality (Redemptorist Communications), March 2022 (Vol 88 No 2 ISSN 0034-0960), pp 12-16.

‘Study 4: Celtic Spirituality: A View from the Church of Ireland’,

Living Stones, Living Hope, USPG Lent Study Course 2022 (London: USPG, 2022, ISBN: 2631-4995), pp 29-34.

Book Review:

Fifty Catholic Churches to See Before You Die. By Elena Curti. Leominster: Gracewing, 2000. Pp 280. Price £14.99 (pbk). ISBN 978-0-85244-962-2, in

The Irish Theological Quarterly (Pontifical University Maynooth), Vol 87 No 1 (February 2022), pp 78-80.

2021:

‘The Meade dynasty in Victorian Dublin and their family roots in Kilbreedy, Co Limerick’, pp 30-32 in

ABC News (2021), annual magazine of Askeaton/Ballysteen Community Council Muinitir na Tíre, ed Geraldine O’Brien and Teresa Wallace.

‘Returning to a place of spiritual sanctuary in the chapel of Saint John’s Hospital, Lichfield’

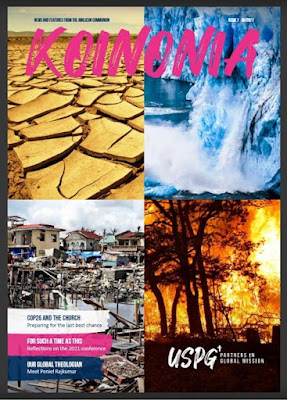

Koinonia (Kansas City MO, December 2021), pp 22-25.

‘Albert Grant, the Victorian Fraudster Born in Poverty in Dublin’ (Chapter 23, pp 104-107),

Birth and the Irish: a miscellany, Salvador Ryan, ed (Dublin: Wordwell Books, 2021, 288 pp, ISBN: 978-1-913934-61-3).

‘Six Boys from Ballaghadereen with the Same Parents … but who was Born the Legitimate Heir?’ (Chapter 32, pp 144-148),

Birth and the Irish: a miscellany, Salvador Ryan, ed (Dublin: Wordwell Books, 2021, 288 pp, ISBN: 978-1-913934-61-3).

‘A Reflection on the Crises in Afghanistan following the Fall of Kabul’,

Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review (Vol 110, No 440, Winter 2021, pp 458-469).

Book Review:

The Churchwardens’ Accounts of the Parishes of St Bride, St Michael Le Pole and St Stephen, Dublin, 1663-1702. Edited by WJR Wallace. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2020. Pp. 208. Price €50.00 (hbk). ISBN 978-1-84682-835-5, in

The Irish Theological Quarterly, (Pontifical University Maynooth) Vol 86 No 2 (May 2021), pp 213-215.

Photographs in: Michael Christopher Keane,

The Crosbies of Cork, Kerry, Laois and Leinster (2021, viii + 321 pp), ISBN: 9781527297418.

Photograph, illustrating Dr Dani Scarratt and Alison Woof, ‘Coming to our senses’ (pp 21-27),

Case Quarterly No 60 (2021), pp 21-27 (Centre for Christian Apologetics, Scholarship and Education, New College, University of New South Wales, Sydney).

Photograph: Saint Mary’s Cathedral, Limerick, cover photograph,

Old Limerick Journal (No 56, Winter 2021), ed Tom Donovan, published by the Limerick Museum.

2020:

‘The banking heir who claimed a title and whose father was Vicar of Askeaton’,

ABC News 2020, annual magazine of the Askeaton/Ballysteen Community Council Muintir na Tíre (Askeaton, December 2020), pp 72-74.

‘Saint Mary’s, The Parish Church that Looks Like Part of the College’,

We Remember Maynooth: A College across Four Centuries, eds Salvador Ryan and John-Paul Sheridan (Dublin: Messenger Publishing, 2020, 512 pp), ISBN 9781788122634, pp 36-38.

‘A Day in the Sun in mid-November 1987 with RTÉ and the Cardinal’,

We Remember Maynooth: A College across Four Centuries, eds Salvador Ryan and John-Paul Sheridan (Dublin: Messenger Publishing, 2020, 512 pp), ISBN 9781788122634, pp 366-370.

Book Review,

The Lost Art of Scripture: Rescuing the Sacred Texts, Karen Armstrong, London: The Bodley Head, 2019, pp 549 pp, £25, ISBN 978-1-847-92431-5, in

Search, A Church of Ireland Journal, Vol 43, No 3 Autumn 2020 (October 2020), pp 231-232.

Book Review,

Irish Theological Quarterly, Vol 85, No 3 (Pontifical University Maynooth, August 2020), pp 323-325:

Irish Anglicanism, 1969-2009: Essays to mark the 150th anniversary of the Disestablishment of the Church of Ireland, Edited by Kenneth Milne and Paul Harron. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2019. Pp. 304. Price €35.00 (hbk). ISBN 978-1-84682-819-5.

‘Are ‘conservative evangelicals’ really conservative and evangelical?’

Search, a Church of Ireland journal, Vol 43 No 1 (Spring 2020), pp 5-13.

2019:

‘Chichester Phillips: the MP for Askeaton who gave Ireland its first Jewish Cemetery’,

ABC News 2019 (pp 61-63), the annual magazine of Askeaton/Ballysteen Community Council Muintir na Tíre (December 2019)

‘Wellington: the Irish hero at Waterloo who introduced Catholic Emancipation’, Hugh Baker and John McCullen (eds),

Drogheda Grammar School, 1669-2019 (Drogheda: Drogheda Grammar School, 2019, xii + 236 pp), pp 31-37.

‘John Leslie, the ‘oldest bishop in Christendom’, Chapter 15, pp 50-52, Salvador Ryan (ed),

Marriage and the Irish (Dublin: Wordwell, 2019).

‘Four Victorian weddings and a funeral’ Chapter 47, pp 163-165, Salvador Ryan (ed),

Marriage and the Irish (Dublin: Wordwell, 2019).

Book Review,

The Future of Religious Minorities in the Middle East, John Eibner (ed), Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2018, pp 276. ISBN 978-14985-6196-9, in

Search: A Church of Ireland Journal Vol 42.2, Summer 2019 (June 2019), pp 151-152.

2018:

‘Once in Royal David’s City’: celebrating two anniversaries of a favourite Christmas carol’

Reality Vol 83, No 10 (December 2018), (Dublin: Redemptorist Communications, ed Brendan McConvery CSsR) pp 24-27.

‘A curious link between Askeaton and a plot to kill two kings,’ in

ABC News 2018 (December 2018), the annual magazine of Askeaton/Ballysteen Community Council Munitir na Tíre, pp 14-15.

‘Introduction,’ in Robert Wyse Jackson,

Life in the Church of Ireland, 1600-1800, ed John Wyse Jackson (Whitegate, Co Clare: Ballinakella Press, 2018), 256 pp, ISBN 10: 0946538557 ISBN 13: 9780946538553.

‘Pilgrimage visit to Lichfield Cathedral’,

Koinonia, Vol 11, No 36, Trinity I (Kansas City, Missouri, July 2018), pp 20-23.

‘F.J.A. Hort (1828–92), the Dublin-born member of the Cambridge triumvirate and translating the Revised Version of the Bible’, Salvador Ryan and Liam M Tracey (eds),

The Cultural Reception of the Bible: explorations in theology, literature and the arts (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2018, ISBN: 978-1-84682-725-9), pp 189-198.

‘Preaching and Celebrating, Word and Sacrament: Inseparable Signs of the Church’, pp 77-90, in

Perspectives on Preaching: A Witness of the Irish Church, ed Maurice Elliott, Patrick McGlinchey (Dublin: Church of Ireland Publishing, 2018), 242 pp.

‘Ballyragget Castle: A ‘sleeping giant’ with hidden potential’, illustrated feature in

From Tullabarry to Béal Átha Raghdad (Ballyragget, Co Kilkenny: Ballyragget Heritage Festival, 2018), pp 5-8.

2017:

Book reviews:

Jesus: A Very Brief History, Helen K Bond, London, SPCK, 2017, pp 88, ISBN 9780281075997;

Thomas Aquinas: A Very Brief History, Brian Davies, London, SPCK, 2017, pp 137, ISBN 9780281076116;

Florence Nightingale: A Very Brief History, Lynn McDonald, London, SPCK, 2017, pp 127, ISBN 9780281076451; in

Search, A Church of Ireland Journal, Vol 40.3, Autumn 2017 (October 2017), pp 234-236.

‘To praise eternity in time and place … searching for a spirituality of place’,

Ruach No 4 (Michaelmas 2017, Weeford, ed Revd Dr Jason Philips, Ms Lynne Mills), pp 50-56.

‘Marking the Reformation: 500 years on – an Irish Anglican perspective’, in the

Methodist Newsletter, Vol 45, No 487 (Senior Editor, Lynda Neilands; Editor, Peter Mercer), June 2017, pp 24-25.

‘Going to the movies with Harry Potter and Noah’,

Ruach No 3 (Trinity 2017, Weeford, ed Revd Dr Jason Philips, Ms Lynne Mills) pp 28-31.

‘Thomas Cranmer: the Cambridge reformer who shaped the Anglican Reformation’,

Reality, May 2017, pp 38-40 (Dublin: Redemptorist Communications), ed Brendan McConvery CSsR.

‘In the Harrowing of Hell, Christ reaches down and lifts us up with him in his Risen Glory’,

Koinonia (Kansas City MO) vol 10 no 33, Easter 2017 (April 2017), pp 10-13.

2016:

‘Abide with me’: the funeral hymn of a former curate in Co Wexford, Chapter 28 in

Death and the Irish: a miscellany, ed Salvador Ryan (Dublin: Wordwell, 2016, ISBN-13 978-0993351822), pp 108-111.

‘Bringing the bodies home: JJ Murphy and the ‘Pickled Earl’,’ Chapter 40 in

Death and the Irish: a miscellany, ed Salvador Ryan (Dublin: Wordwell, 2016, ISBN-13 978-0993351822), pp 151-154.

‘500 years after Wittenberg, what was Luther’s impact on the Anglican Reformation?’

Koinonia (Kansas MO), Vol 10, No 32 (December 2016), pp 12-16.

‘The Orthodox Church as experienced by an Anglican visitor to Greece,’

Search: A Church of Ireland journal, Vol 39.3 (Autumn 2016), pp 210-218.

‘

Remembering World War I’: an introuction (pp 1-3) to ‘A Service of the Word for a Commemoration of the First World War in a local church’, on-line liturgical resource (Dublin: Church of Ireland, 2016, 16 pp).

Book review:

Ethics at the Beginning of Life, A phenomenological critique, James Mumford, Oxford: Oxford University Press (Oxford Studies in Theological Ethics series) 2015. 212 pages. ISBN 978-0-19874505-1; in

Search, A Church of Ireland Journal, Vol 39.3, Autumn 2016 (October 2016), pp 233-235.

Photograph in: Mairéad Carew,

Tara, The Guidebook (Dublin: Discovery Programme, Royal Irish Academy, 2016), p 88.

‘John Alcock’ in David Wallington (ed),

Friends of Lichfield Cathedral, 79th Annual Report (Lichfield, 2016), pp 28-31.

‘O Come All Ye Faithful – the Christmas carol with forgotten links with Lichfield Cathedral’, in David Wallington (ed),

Friends of Lichfield Cathedral, 79th Annual Report (Lichfield, 2016), pp 42-48.

‘Samuel Johnson: a literary giant and a pious Anglican layman’,

Koinonia, vol 9 no 30, Lent/Easter 2016 (March 2016), pp 22-26.

Book Review:

The God We Worship, an exploration of liturgical theology, Nicholas Wolterstorff, Grand Rapids, Michigan, and Cambridge, Eerdmans, 2015, pb, xi + 192 pp, ISBN: 978-0-8028-7249-4, in

Search, A Church of Ireland Journal Vol 39.1, Spring 2016 (March 2016), pp 68-69.

‘The Eucharist or Holy Communion in the Church of Ireland and Anglicanism’,

Reality Vol 81, No 1, January/February 2016, pp 14-17 (Dublin: Redemptorist Communications), ed Brendan McConvery CSsR.

Photograph in:

Peaks Postings, vol 10, issue 1, the magazine of the Presbytery of the Peaks, Virginia (January 2016).

2015:

‘Why are faith groups so concerned about civil legislation?’, pp 48-50 in

Yes We Do, ed Denis Staunton (ebook, Dublin: Irish Times Books, 2015)

‘O come, all ye faithful’: the story of the most popular Christmas carol,

Koinonia, Vol 9 No 29, Advent/Christmas 2015 (Kansas City MO, December 2015), pp 24-27.

‘Henry Bate Dudley (1745-1824): the ‘fighting parson’ who retained an affection for his County Wexford parish’,

Journal of the Wexford Historical Society, No 25, 2014-2015 (Wexford, 2015), pp 44-62.

Photograph in: Professor M Harunur Rashid,

Cambridge: Look Back in Love (Dhaka, Bangladesh: MetaKave Publications, 2015).

Hooker’s understanding of justification – finding the Anglican ‘middle way’,

Koinonia, vol 8, no 28, Trinity I and II 2015 (Kansas City MO, September 2015), pp 5-7.

‘Why are faith groups so concerned about civil legislation?’ pp 48-50 in

Yes We Do, ed Denis Staunton (Dublin: Irish Times Books, 2015, eBook).

‘Richard Church (1784-1873): An Irish Anglican in the Greek Struggle for Independence’

Treasures of Ireland, Vol III, To the Ends of the Earth, Salvador Ryan (ed), (Dublin: Veritas, 2015), pp 117-120.

‘The Dublin Family Who Became Missionary Martyrs in China,’

Treasures of Ireland, Vol III, To the Ends of the Earth, Salvador Ryan (ed), (Dublin: Veritas, 2015), pp 142-145.

‘Introducing Spirituality and Cinema … Who are these like stars appearing?’

Koinonia, Lent/Easter 2015, Vol 8, No 27 (Kansas City MO, April 2015), pp 14-18.

‘I do not like thee, Doctor Fell … but you are a child of Lichfield Cathedral,’

Friends of Lichfield Cathedral, 78th Annual Report, 2015 (ed, David Wallington), pp 42-47.

2014:

‘Half a century after his death, TS Eliot remains the greatest Anglo-Catholic poet’,

Koinonia, Christmas/Epiphany 2014-2015, Vol 8, No 27 (Kansas City MO, December 2014), pp 13-17.

‘Seeing ‘the glory of the Lord’ in Kempe’s carvings on the triptych in the Lady Chapel’, Spring Edition of

Three Spires (Lichfield) and

Friends of Lichfield Cathedral, 77th Annual Report, 2014 (ed, David Wallington), pp 31-36.

‘Mid-Lent is passed and Easter’s near, The greatest day of all the year’ … John Betjeman, an Anglo-Catholic Poet,

Koinonia, Vol 7, No 25, Lent/Easter 2014 (Kansas City MO, April 2014), pp 12-16.

‘A one-name study that disentangles myths about the origins of the Comerford family’,

Ireland Region Newsletter, Guild of One-Name Studies, pp 1-5, April 2014.

Book review:

The Lion’s World: a journey into the heart of Narnia, Rowan Williams, London, SPCK, 2012, xiii + 152 pp, paperback, £8.99, ISBN 978-0-281-06895-1; in

Search, A Church of Ireland Journal Vol 37, No 1, Spring 2014 (March 2014), pp 71-72.

‘The corner kiosk: An essential part of the Greek way of life,’

Neos Kosmos / Νέος Κόσμος (Melbourne, 3 January 2014).

2013:

‘Josiah Hort (1674?-1751), Bishop of Ferns: ‘A Rake, a Bully, a Pimp, or Spy’ and ‘Bp Judas’,’

Journal of the Wexford Historical Society, No 24, 2012-2013 (Wexford, 2013), pp 94-114, ISSN 0790-1828.

‘An Anglican apologist and a literary giant: recalling CS Lewis 50 years after his death’,

Koinonia, vol 7 No 24, Christmas, 2013 (Kansas, Missouri, December 2013), pp 5-9.

‘The Centenary of the Anglican Church, Bucharest: 1913-2013’,

Romanian Studies (Bucharest: Centre for Romanian Studies, 10 December 2013),

https://www.romanianstudies.org/2013/12/10/the-rev-canon-patrick-comerford-on-the-centenary-of-the-anglican-church-bucharest-1913-2013/#more-5581

‘Crete’s icon writers: a living tradition offering new opportunities for mission’

Koinonia, vol 7 No 24, (Christmas 2013 (Kansas, Missouri, December 2013), pp 20-21.

‘Agia Irini: a newly-restored Byzantine monastery in Crete’,

Koinonia vol 6 no 23, Trinity II, 2013 (Kansas, Missouri, October 2013), pp 12-13.

‘Comerford Monuments in Callan and the Search for a Family’s Origins’, Chapter 2 (pp 23-39) in

Callan 800 (1207-2007) History & Heritage, Companion Volume, ed Joseph Kennedy (Callan: Callan Heritage Society), 2013.

‘Bale’s Books and Bedell’s Bible: Early Anglican Translations of Word and Liturgy into Irish’, Salvador Ryan and Brendan Leahy (eds),

Treasures of Irish Christianity, Volume II, A People of the Word (Dublin: Veritas, 2013, ISBN 978–1–84730–431–5), pp 124-128.

‘Thou my high tower’: The Celtic Revival and Hymn Writers in the Church of Ireland,’ in Salvador Ryan and Brendan Leahy (eds),

Treasures of Irish Christianity, Volume II, A People of the Word (Dublin: Veritas, 2013, ISBN 978–1–84730–431–5), pp 203-206.

'Deacons, the Diaconate and Diakonia: The Church of Ireland experience,’ pp 6-11 in ‘Companion Papers to Truly Called … Two’ (Edinburgh: Scottish Episcopal Church), April 2013.

‘Being an Anglican in a pluralist and suffering world’,

Oscailt (Dublin, vol 9, no 3, March 2013), pp 2-7.

‘The Finest Expressions of Anglican Piety at its Best: Lent and Easter with George Herbert’,

Koinonia, vol 6, no 21, Lent 2013 (Kansas, Missouri, March 2013), pp 14-18.

‘An Irish Anglican Response to Vatican II,’

Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, vol 101, no 404, Winter 2012/2013 (Dublin, February 2013), pp 441-448.

Photograph in: ‘Serbian Theological Seminarians in Great Britain: Cuddesdon Theological College 1917–1919: Appendices and Supplements I’, in

Serbian Theology in the Twentieth Century: Research Problems and Results, vol 14, Proceedings of the Scientific Conference (PBF/FOT Belgrade, 24 May 2013), ed B Šijaković, Belgrade: Faculty of Orthodox Theology 2013, 52-127: 111.

2012:

Two photographs in: Maurice Curtis,

Portobello (Dublin: The History Press, 2012), 128 pp, ISBN: 9781845887377, p. 25.

‘Anglo-Catholicism’,

Koinonia, Vol 5, No 19, Trinity 2, 2012 (Kansas, Missouri, January 2012), p 3.

‘Finding hope in Greece in the midst of economic and financial crises’,

Koinonia, Vol 5, No 19, Trinity 2, 2012 (Kansas, Missouri, January 2012), pp 3-6.

‘In Retrospect: Gonville Aubie ffrench-Beytagh’,

Search, a Church of Ireland Journal, 35/1, Spring 2012 (February 2012), pp 47-54.

Book Review:

The Works of Love: incarnation, ecology and poetry, John F Deane, Dublin, Columba Press, Paperback, 416 pp, €19.99 / £16.99, ISBN 9781856077095), in

Search – a Church Ireland Journal Vol 35, No 1, Spring 2012 (February 2012), pp 63-65.

Book review:

Letters from Abroad: The Grand Tour Correspondence of Richard Pococke & Jeremiah Milles, Vol. 1: Letters from the Continent (1733-1734), edited by Rachel Finnegan. Piltown, Co Kilkenny, Pococke Press, 2011. Pb, 336 pp, ISBN: 978-0-9569058-0-2), €18; in

Astene Bulletin, Notes and Queries, No 50, Winter 2011-12 (London: Association for the Study of Travel in Egypt and the Near East, February 2012).

2011:

‘Advent, a time of preparation for the coming of Christ’,

Koinonia, Vol 5, No 13, Advent 2011 (Kansas, Missouri, December 2011), pp 3-6.

‘James Comerford (1817–1902): rediscovering a Wexford–born Victorian stuccodore’s art’,

Journal of the Wexford Historical Society, No 23 (2011-2012), pp 4-32 (Wexford, November 2011).

‘The springtime of the Fast has dawned, the flower of repentance has begun to Open’,

Koinonia, Vol 4, No 13, Lent 2011 (Kansas, Missouri, March 2011) pp 10-13.

Photographs of Saint Edan’s Cathedral, Ferns, Co Wexford, in:

Madoc 24/1, illustrating René Broens, ‘Madoc in Madoc’ (pp 13-21); specialist journal on the Middle Ages, edited in Utrecht and published in Hilversum by Uitgeverij Verlorem.

2010:

‘Anglo–Catholicism: Relevant after 175 years?’,

Koinonia, vol 4, No 12, Christmas 2010 (Kansas City, Missouri, December 2010), pp 13-23.

Photograph and text: ‘Memorial plaque to … Henry Wallop …’,

Enniscorthy, A History, ed Colm Tóibín (Wexford: Wexford County Council Public Library Services, 2010, ISBN 978-0-9560574-7-1), pp 122-123.

‘Bishop Joseph Stock (

ca 1740-1813) and the Clergy of the Diocese of Killala and Achonry during the 1798 Rising’,

Victory or Glorious Defeat?: Biographies of Participants in the Great Rebellion of 1798 (Westport: Carrowbaun Press, Dublin: Original Writing, 2010, ISBN: 978–1–907179–75–4), pp 113-145.

‘Heroism and Zeal’: Pioneers of the Irish Christian Missions to China,

China and the Irish (Mandarin translation, Beijing: People’s Publishing House, 2010, ISBN 978–7–01–009194–5), pp 77-92.

Photographs in: René Broens, ‘Madoc in Madoc,

Madoc 24/1 (Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verlorem, August 2010), pp 13-21, specialist journal on the Middle Ages.

2009:

A Romantic Myth? Kilcronaghan’s link to ‘Zorba the Greek’ (Tobermore: Kilcronaghan Community Association, in association with Magherafelt Arts Trust, January 2009), pamphlet.

‘Celebrating the Oxford Movement’, Chapter 1 (pp 7-34) in

Celebrating the Oxford Movement (Belfast: Affirming Catholicism Ireland, 2009), ACI Occasional Papers 1.

Contributor to:

Health Services Intercultural Guide: Responding to the needs of diverse religious communities and cultures in healthcare settings (Dublin: Health Service Executive, 2009, 226 pp, ISBN: 978-1-906218-21-8), April 2009.

2008:

Book Review (‘House of Gold’):

St Paul’s Ephesus: Texts and Archaeology, by Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, Liturgical Press/Michael Glazier, 289 pp, $29.95, ISBN 978-0814652596,

Dublin Review of Books, December 2008.

The Anglo–Catholic Movement: more relevant today than ever? (Dublin: Saint Bartholomew’s Parish, 2008), 24 pp pamphlet.

Reflections of the Bible in the Quran: a comparison of Scriptural Traditions in Christianity and Islam (Dublin: National Bible Society of Ireland, 2008), ISBN: 978 0 9548 6723. (Bedell–Boyle lecture series, Bedell-Boyle lecture in the Milltown Institute for Philosophy and Theology, Dublin, 2006).

‘Foreword’,

Mainland Chinese Students and Immigrants and their Engagement with Christianity, Churches and Irish Society (Dublin: Agraphon Press for Dublin University Far Eastern Mission and China Education and Cultural Liaison Committee, 2008).

‘Matching prayer life and spirituality with temperament and personality’,

Search 31/1 (January 2008), pp 37-45.

‘The Fifth Sunday of Epiphany’,

A Year of Sermons at Saint Patrick’s Dublin, ed, Robert MacCarthy (Dublin: Typemasters, 2008), pp 19-22.

‘The Spirituality of Icons’, in

Panhellenic Society of Iconographers and Dimitris Kolioussis, ed Richard Gordon (Derry: Gordonart Publications, 2008), exhibition catalogue, January 2008 (Exhibition catalogue, in collaboration with the Hellenic Foundation for Culture and Christ Church Cathedral Dublin).

2007:

Embracing Difference: The Church of Ireland in a Plural Society (Dublin: Church of Ireland Publishing, 2007), 88 pp, ISBN-10: 190488413X, ISBN-13: 978-1904884132.

(Anonymously):

Guidelines for Interfaith Events and Dialogue, the Committee for Christian Unity and the Bishops of the Church of Ireland, 32 pp pamphlet (Dublin: Church of Ireland Publishing, 2007).

‘Anglican-Orthodox Dialogue: open door or distant object?’,

Search 30/2 (Dublin, 2007) pp 141-152.

‘Prayer, spirituality and liturgy in the Orthodox tradition’,

Affirming Catholicism Ireland Newsletter, Epiphany 2007 (January 2007).

‘Sir Richard Church and the Irish Philhellenes in the Greek War of Independence’, opening chapter in

The Lure of Greece, eds JV Luce, C Morris, C Souyoudzoglou-Haywood (Dublin and Athens: Hinds/Irish Institute of Hellenic Studies, Athens, in association with the Department of Classics, TCD, 2007), pp 1-18.

‘The Hon Percy Jocelyn (1764–1843): Bishop of Ferns and the “most idle of all reverend idlers”,’ chapter in

The Wexford Man: Essays in Honour of Nicky Furlong (ed Bernard Browne), festschrift to Nicky Furlong (Dublin: Geography Publications, 2007), pp 39-47.

2006:

From Mission to Independence: Four Irish bishops in China (Dublin and Shanghai: Dublin University Far Eastern Mission, 2006), 24 pp pamphlet.

‘Pastoral issues in Muslim-Christian relations’,

Search 29/2 (Dublin, 2006), pp 152-157.

‘The Reconstruction of Theological Thinking – what are the implications for the Church in China?’,

Search 29/1 (Dublin, 2006), pp 13-22.

(Anonymously)

The Hand of History (Dublin and Belfast: CMS Ireland, 2006), study pack on Christian-Muslim dialogue.

2005:

‘Edmund Comerford (d. 1509) and William Comerford (ca 1486–1539): the last pre-Reformation Bishop of Ferns and his ‘nephew’, the Dean of Ossory’,

Journal of the Wexford Historical Society, Vol 20 (Wexford, 2005), pp 156-172.

‘The Bishop of Meath and the Ratoath impostor: Thomas Lewis O’Beirne (1748–1823) and Laurence Hynes Halloran (1765–1831)’,

Ríocht na Midhe, Journal of the Meath Archaeological and Historical Society, vol 16 (Navan, 2005), pp 69-82.

2003:

‘Cead Mile Failte to Repentance and Reconciliation’, chapter in

Untold Stories: Protestants in the Republic of Ireland 1922–2002, eds C Murphy, L Adair (Dublin: Liffey Press, 2003).

‘Just war and jihad: whose holy war in Iraq?’,

Search 26/2 (Dublin, 2003), pp 65-73.

‘The Fethard Boycott’,

The Encyclopaedia of Ireland, ed Brian Lalor (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan / New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003). Encyclopaedia entry on the Fethard-on-Sea boycott in Co Wexford.

2002:

‘A Schism or a Tradition? The Church of Ireland and the Nonjurors’,

Search 25/2 (Dublin, 2002), pp 100-111.

‘An innovative people: the laity, 1780–1830’, chapter in

The laity and the Church of Ireland, 1000–2000: All Sorts and Conditions, eds. R Gillespie, WG Neely (Dublin: Four Courts, 2002).

‘Understanding Islam – A Year after 11 September’, Doctrine and Life 52/2 (Dublin: Dominican Publications, 2002), pp 396-404.

‘Vienna plays pivotal role in promoting dialogue with Islamic world’,

Euro–Med dialogue between Cultures and Civilizations: the Role of the Media, eds E Brix, M Weiss (Vienna: Diplomatic Academy, Favorita Papers, special ed, 2002), pp 32-34.

2001:

‘A Brief History of Christianity’, Part 2 of

Christianity, ed Patsy McGarry (Dublin: Veritas, 2001); co–authors Hans Küng, Desmond Tutu, Mary Robinson, &c.

‘Bishop Ricards and Dean Croghan: The contrasting tale of two Wexford missionaries in South Africa’,

Journal of the Wexford Historical Society (Wexford, 2001), pp 21-44.

‘Pilgrimage to Patmos: Jerusalem of the Aegean and Mount Athos of the islands’,

Spirituality 7/37 (Dublin: Dominican Publications, 2001), pp 210-213.

2000:

‘Apartheid, Myth and Reality’,

Tribute to Nelson Mandela, ed Louise Asmal (Dublin: IAAM, 2000), pp 11-13.

‘Defining Greek and Turk: Uncertainties in the Search for European and Muslim identities’,

Cambridge Review of International Affairs 13/2 (Cambridge: Centre of International Studies, University of Cambridge, 2000), pp 240-253.

.

‘Genealogies, Myth-making, and Christmas,

Doctrine and Life 50/11 (Dublin: Domincan Publications, 2000), pp 552–556.

‘Simon Butler and the forgotten role of the Church of Ireland during the 1798 Rising’,

Journal of the Butler Society (Kilkenny, 2000), pp 271-279.

1999:

‘Edward Nangle (1799–1883): the Achill Missionary in a New Light’,

Search 22/2 (Dublin, 1999), pp 123-136.

‘Edward Nangle (1799–1883): the Achill Missionary in a new light, Part II’,

Cathar na Mairt, Journal of the Westport Historical Society, 19 (Westport, 1999), pp 8-22.

‘From India to Brazil: Nicholas Comerford, a seventeenth-century Kilkenny cartographer’,

Old Kilkenny Review, Journal of the Kilkenny Archaeological Society (Kilkenny, 1999), pp 92-102.

‘Star Wars: new age theology or exploiting the children?’,

Doctrine and Life 49/8 (Dublin: Dominican Publications, 1999), pp 494-498.

‘The other Christian traditions’, chapter in

Memory & Mission: Christianity in Wexford 600 to 2000 AD, ed Walter Forde (Wexford: Diocese of Ferns, 1999).

1998:

‘1798: Learning from the Commemorations’,

Doctrine and Life 48/7 (Dublin: Dominican Publications, 1998), pp 405-412.

‘Edward Nangle (1799-1883): the Achill Missionary in a New Light, Part I’,

Cathar na Mairt, Journal of the Westport Historical Society, 18 (Westport, 1998), pp 21-29.

‘Not Forgive and Forget, but Remember and be Reconciled’, Chapter in

From Heritage to Hope: Christian Perspectives on the 1798 Bicentenary, ed Walter Forde (Gorey: Byrne-Perry, 1998).

‘Remembering can unite’, chapter in

From Heritage to Hope: Christian Perspectives on the 1798 Bicentenary, ed Walter Forde (Gorey: Byrne-Perry, 1998).

‘The Church of Ireland in County Kilkenny and the Diocese of Ossory during the 1798 rising’,

Old Kilkenny Review, Journal of the Kilkenny Archaeological Society (Kilkenny, 1998), pp 144-182.

1997:

‘Church of Ireland Clergy and the 1798 Rising’, chapter in

Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter: The Clergy and 1798, ed Liam Swords (Dublin: Columba, 1997).

‘Co Wexford in 1798: Understanding the role of Church of Ireland clergy and laity’,

Search 20/1 (Dublin, 1997), pp 32-41.

‘Euseby Cleaver, Bishop of Ferns, and the clergy of the Church of Ireland in the 1798 Rising in Co Wexford’,

Journal of the Wexford Historical Society (Wexford, 1997), pp 66-94.

1996:

‘Islam and Muslims in Ireland: Moving from Encounter to Understanding’,

Search 19/2 (Dublin, 1996), pp 89-93.

‘A Bitter Legacy?’, chapter in

The Great Famine: A Church of Ireland Perspective, ed Kenneth Milne (Dublin: APCK, 1996).

1994:

‘Arafat visit heralds a new era for Palestinians’, paper in

Prerequisites for Peace in the Middle East (Elsinore, Denmark: UN Department of Public Information, 1994).

‘John Comerford of Ballybur, 1598-1667: Tracing his later life’,

Old Kilkenny Review, Journal of the Kilkenny Archaeological Society (Kilkenny, 1994), pp 23-36.

1992:

Saint Maelruain: Tallaght’s Own Saint (Dublin: Tallaght Parish, 1992). Pamphlet marking parish commemoration of Saint Maelruain.

1991:

‘Compassionate and Passionate – Colin O’Brien Winter (1928–1981)’,

Search 14/2 (Dublin, 1991), pp 34–41.

‘In Prosperity and Adversity’, short story in

True to Type, ed Fergus Brogan (Dublin: Sugarloaf/Irish Times Books, 1991); short story in collection of short stories by Irish Times writers in tribute to the Revd Stephen Hilliard.

‘Zephania Kameeta: Namibia’s Black Liberation Theologian’,

Doctrine and Life 41/3 (Dublin: Dominican Publications, 1991), pp 133-141.

1989:

Desmond Tutu: Black Africa’s Man of Destiny (Hyperion Books, 1989, ISBN: 1853900052), 32 pp.

1988:

Desmond Tutu: Black Africa’s Man of Destiny (Citadel Series 6, 1988).

1987:

Desmond Tutu: Black Africa’s Man of Destiny (Dublin: Veritas; and Athlone: St Paul Publications, 1987, ISBN: 9781853900051), 32 pp Launched by Minister for Foreign Affairs, Brian Lenihan.

1984:

Do You Want To Die for NATO? (Dublin and Cork: Mercier Press, 1984). Launched by Senator Brendan Ryan.

1983:

‘The Storm that Threatens: A comment’,

The Furrow (Maynooth) 34/10 (1983), pp 620-625.

‘ML King’,

Dawn Train (Dublin, an Irish journal of nonviolence), No 2, Spring 1983 (special edition, ‘Parents of Nonviolence’), pp 3-5.

‘Dietrich Bonhoeffer’,

Dawn Train (Dublin, an Irish journal of nonviolence), No 2, Spring 1983 (special edition, ‘Parents of Nonviolence’), pp 6-7.

1981:

‘Political theology, theological politics: Nuclear Insanity’,

Springs (Birmingham and Dublin: Student Christian Movement) 1981.

1976:

Paper and illustration in

Eamon de Valera, ed PT O’Mahony (Dublin: Irish Times Books 1976).

1973:

‘The Early Society of Friends … in Kilkenny’

Old Kilkenny Review (Kilkenny, 1973).

Journalism:

The Irish Times: Staff journalist, 1974-2002; Foreign Desk Editor, 1994-2002; continuing to contribute as occasional feature writer and leader writer.

The Wexford People: Staff journalist, 1972-1974; Contributor to

Wexford People,

Enniscorthy Guardian,

Gorey Guardian,

New Ross Standard,

Wicklow People,

Ireland’s Own. Latest contributions, 2022 (news and features).

Lichfield Mercury: freelance journalist, 1970-1973.

Rugeley Mercury: freelance journalist, 1970-1973.

Tamworth Herald: freelance journalist, 1970-1973.

Editor,

What’s On In Wexford (Wexford Junior Chamber), 1973-1974.

Editor,

Unity, quarterly magazine, Irish School of Ecumenics, Trinity College Dublin, in the 1990s.

Features and reports in:

Athens News;

CityLife Lichfield;

Church of Ireland Gazette, features and editorial writer;

Church Review (Dublin and Glendalough), monthly feature;

Church Times;

Diocesan Magazine (Cashel, Ferns and Ossory), monthly feature;

EnetEnglish, an online news service from

Eleftherotypia;

Horse and Hound;

Ireland’s Own;

Lichfield Gazette;

Newslink (Limerick and Killaloe); MultiKulti.gr; Neos Kosmos (

Real Corfu); photographs in

Limerick Leader (2018, 2020, 2022) and

Clare Echo (2022).

Last updated: 1 July 2025

Ramadan bread on sale as sunset draws in Kuşadasi (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Ramadan bread on sale as sunset draws in Kuşadasi (Photograph: Patrick Comerford) ‘The springtime of the Fast has dawned, the flower of repentance has begun to Open’ … an image in the journal Koinonia, Lent 2011, Vol 4, Issue 13, Kansas City, MO

‘The springtime of the Fast has dawned, the flower of repentance has begun to Open’ … an image in the journal Koinonia, Lent 2011, Vol 4, Issue 13, Kansas City, MO Sunset in the Aegean at Ladies Beach in Kuşadasi … practising Muslims are expected to fast from sunrise to sunset each day during Ramadan (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Sunset in the Aegean at Ladies Beach in Kuşadasi … practising Muslims are expected to fast from sunrise to sunset each day during Ramadan (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)