Patrick Comerford

John Henry Newman is to be declared a Doctor of the Church, Pope Leo has announced in recent days. He is the 38th Doctor of the Church recognised by the Vatican, and the third to be associated with England, after the Venerable Bede and Saint Anselm of Canterbury.

John Henry Newman (1801-1890) is celebrated in the calendar of the Church of England today (11 August), the anniversary of his death in 1890, but in the Roman Catholic Church on 9 October, the anniversary of his reception into that Church in 1845.

Newman was one of the most influential figures in Church life in both England and Ireland in the 19th century. He is remembered in England as the most prominent member of the Oxford Movement, reconnecting Anglicanism with its Catholic roots and heritage, and in Ireland as the founding rector of the newly-formed Catholic University of Ireland in 1854. He was also the founding figure in the Newman University Church which built on Saint Stephen’s Green, Dublin, in 1855-1856.

John Henry Newman was born at 80 Old Broad Street on 21 February 1801 and was baptised in Saint Benet Fink on 9 April 1801 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Newman was canonised a saint in Rome six years ago [13 October 2019], and was beatified 15 years ago on 19 September 2010 by Pope Benedict XVI during his four-day visit to England.

The future Cardinal John Henry Newman was born at 80 Old Broad Street, London, on 21 February 1801 and was baptised in Saint Benet Fink Church on 9 April 1801. At an early stage in life he was seen as evangelical background in the Church of England. He studied at Trinity College Oxford, and became a Fellow of Oriel College, Oxford, in 1822. He was ordained deacon in Christ Church, Oxford, in 1824, priest in 1825.

Newman remained a fellow of Oriel College from 1822 to 1845. During those years he was also the college chaplain (1826-1831, 1833-1835) and Vicar of the University Church of Saint Mary the Virgin (1828-1843).

Tom Tower and the Quad at Christ Church, Oxford, where Newman was ordained (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Newman went on a holiday in Italy in 1832 with his friend Richard Hurrell Froude (1801-1836) of Oriel College and his father. He left them in Rome as he travelled on to Sicily, but there he became gravely ill with a fever. When he recovered, the weather delayed his return to England and he was forced to stay on board his ship for a further three weeks.

During those weeks, he wrote one of his best-known and best-loved poems and hymns, ‘Lead, kindly light, amid the encircling gloom’. The poem expresses his sense of complete uncertainty and disorientation, and reveals his sense of groping in the darkness, pleading with God to lead and guide him.

The University Church of Saint Mary, where Newman was Vicar during his days in Oxford (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

On the Sunday he returned to Oxford, 14 July 1833, Newman heard John Keble (1792-1866), Professor of Poetry at Oxford, preach his famous ‘Assize Sermon’ in Newman’s own church, the University Church of Saint Mary the Virgin.

Keble’s sermon was an attack on state interference in church affairs, prompted by government moves to reform the diocesan structures of the Church of Ireland, and is now regarded as the beginning of the Oxford Movement.

Newman became the driving force behind the Oxford Movement, alongside Keble and Edward Bouverie Pusey (1800-1882), and Oriel is pre-eminently the college of the Oxford Movement, the first phase of which lasted from 1833-1845. Its proponents produced the Tracts for the Times, a series of 90 tracts that gave them the name ‘Tractarians’, and Newman wrote 27 of the tracts.

Besides Newman, Keble and Pusey, other figures of the movement associated with Oriel included Robert Wilberforce (1802-1857), Richard Hurrell Froude (1803-36), GA Denison (1805-1896), Thomas Mozley (1806-1893), Charles Marriott (1811-1858) and RW Church (1815-1890). Richard Whately (1787-1863) was a fellow of Oriel (1811-1821) and Drummond Professor of Political Economy in Oxford (1830-1831) before becoming Archbishop of Dublin (1831-1863).

Oriel College is pre-eminently the college of the first phase of the Oxford Movement (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Many of the Tractarians met in the Rectory in Calverton, near Stony Stratford, including Newman, Pusey, and Edward Manning, and some of the Tracts for the Times were planned if not written at Calverton. At the time, the Revd the Hon Charles George Perceval (1796-1858) was the Rector of Calverton. He was of Irish descent, a devout High Churchman and a supporter of the Tractarians. He came to Calverton in 1821 at the relatively young age of 24, and was a younger brother of George Perceval (1794-1874), who became the 6th Earl of Egmont in 1841.

Meanwhile, Newman was gaining a reputation as a poet and his edited collection, Lyra Apostolica, including ‘Lead, kindly light’, was published in 1836.

In a seminal exposition of Anglicanism in his Prophetical Office of the Church (1837), Newman maintained that the essential points of Anglicanism are its doctrine, its sacramental system and its legitimate claims to be the Catholic Church in England. However, he reached a turning point in 1841 with Tract 90, in which he tried to reconcile the 39 Articles with the decrees of the Council of Trent and the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church.

Newman was censured by the university and was silenced by the Bishop of Oxford. He resigned from Saint Mary’s in 1843, and after considerable hesitation became a Roman Catholic and was received into the Roman Catholic Church by Dominic Barbieri on 9 October 1845.

He defended this decision in his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine. Five years later, the Roman Catholic hierarchy was officially founded in England and Wales. Newman founded the Oratory of Saint Philip Neri in Birmingham, and remained at the Oratory in Birmingham for the rest of his life – apart from a few short years in Dublin.

At the time of Newman’s move, Roman Catholicism in England was going through a traumatic transition. Until the early 19th century, it was dominated by the old landed recusant families – the sort of families who would later figure in Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisted. But it was changing with the increasing influx of poor Irish immigrants, and Birmingham became the heart of the Irish slums in the English Midlands.

Newman House, where Newman was Rector of the Catholic University of Ireland, and Newman University Church on Saint Stephen’s Green, Dublin (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2024)

In 1854, Newman moved to Dublin, and for four years he was rector of the newly-founded but short-lived Catholic University of Ireland. His plans for a university were frustrated, yet his stay in Ireland saw him publish his The Idea of a University.

Newman lived at Mount Salus in Dalkey during the autumn of 1854 while he was establishing the Catholic University in Dublin. He wrote, ‘Tastes so differ that I do not like to talk, but I think this is one of the most beautiful places I ever saw.’

His college chapel survives as Newman University Church on Saint Stephen’s Green, beside Newman House, the Department of Foreign Affairs at Iveagh House, and the former sites of the Methodist Centenary Church and Wesley College.

The University Church was designed by John Hungerford Pollen, who was invited to Dublin by Newman as Professor of Fine Art. Newman rejected Pugin’s Gothic style, seeing in it echoes of the pagan forests of Northern Europe; but he also associated the classical style with his Anglican past and Greek and Roman paganism. And so, he favoured the Byzantine style for his university church.

Pollen’s design is the only successful Byzantine-style church in Ireland, and shows the influence of John Ruskin’s Stones of Venice.

Newman House on Saint Stephen’s Green now houses the Museum of Literature Ireland and backs onto the Iveagh Gardens.

Newman University Church, Saint Stephen’s Green, Dublin … celebrating John Henry Newman today (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2024)

Practical organisation was not among Newman’s gifts, and after four unhappy years in Dublin he returned to Birmingham. Little did he know that his efforts to establish a university in Ireland would eventually bear fruit in University College Dublin. The Literary and Historical Society (L&H), which he founded, remains one of the best-known university debating societies in Ireland.

Back in England, a controversy in 1863 and 1864 involving the Anglican social reformer, Charles Kingsley, led Newman to publish his Apologia pro Vita Sua, earning his place as one the greatest Catholic minds of his time. His other great works include The Dream of Gerontius (1865) and the Grammar of Assent (1870).

Newman was not uncritical of his new Church. His opposition to the Pope’s retention of temporal powers led to a breach in his friendship with Cardinal Manning (1801-1892), another former evangelical Anglican and subsequent Tractarian who had been Archdeacon of Chichester and then became Archbishop of Westminster in 1865 and a cardinal in 1875.

Yet Newman retained many Anglican friends throughout his life, including Richard Church, Dean of Saint Paul’s Cathedral, London, and a nephew of Sir Richard Church, the Cork-born liberator of Greece. He read Anthony Trollope’s Barchester Towers on the recommendation of Pollen. When Newman heard of Kinglsley’s death he acknowledged Kingsley’s role in prompting his Apologia, his defence of the Athanasian Creed, and how he had preached kindly about Newman in Chester Cathedral, and added: ‘I said Mass for his soul as soon as I heard of his death.’

A copy of the portrait of Newman as a cardinal, by Sir John Everett Milais, in Newman University Church, Dublin (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

A copy of the portrait of Newman as a cardinal, by Sir John Everett Milais, in Newman University Church, Dublin (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)Although never a bishop, Newman was made a cardinal by Pope Leo XIII in 1879 at the suggestion of the Duke of Norfolk. He chose as his motto Cor ad Cor Loquitor, ‘Heart Speaks to Heart’.

When he died on 27 February 1891, Newman was buried in Rednall Hill, Birmingham, in the same grave as his lifelong friend, Ambrose St John, who lived with Newman as his companion for 32 years. To thwart attempts to make a cult of his remains, Newman ordered that he should be buried in a rich compost so that his corpse would decompose rapidly. When his body was exhumed some years ago in an attempt to retrieve relics, nothing was found except the brass plate and handles of his coffin.

Was Newman a pious Anglo-Catholic who prefigured those Anglican priests who moved to Rome in recent years?

Or was he essentially an Anglican who continued to resist Papal encroachments on the Church and on the conscience of the individual?

What has been called the ‘battle for Newman’s legacy’ took on a new intensity at the time of his beatification with John Cornwell’s book, Newman’s Unquiet Grave: the reluctant saint.

Pope Benedict once claimed that Newman was a faithful supporter of the papal magesterium and pontifical dogmas on many issues, and was an opponent of Catholic dissent. However, John Cornwell portrayed Newman as a dissident when it came to papal authority, infallibility, the downgrading of the laity and the primacy of papal dogma over individual conscience.

‘I shall drink to the Pope if you please,’ Newman once wrote, ‘… still to conscience first and the Pope afterwards.’ He once wrote of the ageing Pope Pius IX: ‘He becomes a god, has no one to contradict him, does not know fact, and does cruel things without meaning it.’

Newman’s hymns include ‘Praise to the Holiest in the height’ and ‘Firmly I Believe’, both from his poem ‘The Dream of Gerontius’. A third, well-loved Newman hymn, ‘Lead, kindly light’, shows how he was never a man for easy answers or the ready acceptance of imposed dogma and authority.

The timber relief of Cardinal John Henry Newman by Sean McDonnell in the Church of the Assumption, Dalkey (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Newman is remembered in the Church of the Assumption in Dalkey, Co Dublin, with a sculpted timber relief by Sean McDonnell. In the same niche is a plaque with the closing words from a sermon Newman preached on 19 February 1843, two years before he became a Roman Catholic: ‘May he support us all the day long, till the shades lengthen and the evening comes; and the busy world is hushed, and the fever of life is over, and our work is done. Then in his mercy may he give us a safe lodging, and a holy rest and peace at the last.’

The legacy of the Oxford Movement continues to inform life at Oriel College, Oxford. The college traditions include singing the ancient hymn Phos Hilaron (‘Hail Gladdening Light’) on feast days and other special occasions.

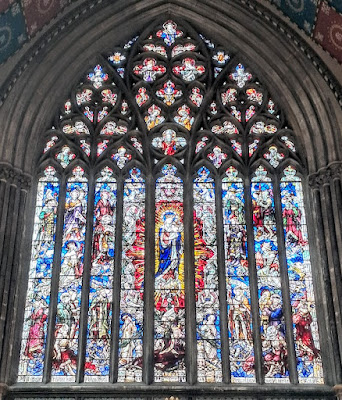

The space once used by both Whately and Newman was rebuilt in 1991 as an oratory and memorial to Newman and the Oxford Movement. A stained-glass window designed by Vivienne Haig and realised by Douglas Hogg was installed in 2001.

Newman has also given his name to one of the five quads at Keble College, Oxford: Liddon, the largest, named after Henry Parry Liddon; Pusey, named after Edward Bouverie Pusey; Hayward, named after Charles Hayward; De Breyne, named after Andre de Breyne; and Newman, previously the Fellows’ Garden.

A well-known prayer by John Henry Newman has been adapted in prayer books throughout the Anglican Communion:

Support us, O Lord,

all the day long of this troublous life,

until the shadows lengthen and the evening comes,

the busy world is hushed,

the fever of life is over

and our work is done.

Then, Lord, in your mercy grant us a safe lodging,

a holy rest, and peace at the last;

through Christ our Lord. Amen.

The oriel above the chapel entrance in Oriel College once formed part of a set of rooms occupied by Archbishop Richard Whately and by Cardinal John Henry Newman (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)