Sir Jacob Epstein’s sculpture in bronze of Bishop Edward Sydney Woods in Lichfield Cathedral … the bishop’s daughter, the photographer, Janet Stone, was married in Lichfield Cathedral and was a friend of John Piper (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

I was writing last night about the stained-glass artist the artist Patrick Reyntiens, who has died recently and who collaborated with John Piper in many of his works, including ‘Christ in Majesty,’ the East Window in the Chapel of Saint John’s Hospital, Lichfield.

John Piper and Patrick Reyntiens may have received the commission for the East Window in Saint John’s because John Piper had several connections with Lichfield. He was commissioned by the Dean of Lichfield, Frederic Iremonger (1878-1952), to design the poster for the cathedral’s 750th Anniversary celebrations in 1947. He also designed a textile cover for the chancel reredos, and John Piper and his wife were close friends of the photographer Janet Woods (1912-1998), daughter of Edward Sydney Woods, Bishop of Lichfield, and her husband, the wood engraver Alan Reynolds Stone. Piper also wrote in 1968 about his admiration for the 16th century Herkenrode Glass in Lichfield Cathedral.

John Piper’s friends, Janet and Reynolds Stone, were distinguished personalities in the arts world their own right: she was an accomplished photographer, while he was a celebrated engraver and typographer. They lived at the Old Rectory in Litton Cheney from 1953 until Reynolds’s death in 1979, but Janet spent a brief time living in the Cathedral Close in Lichfield, and the couple were married in Lichfield Cathedral in July 1938.

Janet Clemence (Woods) Stone was born in Cromer, Norfolk, on 1 December 1912. She was in her mid-20s when she moved briefly to Lichfield in 1937, when her father, Edward Sydney Woods (1877-1953), became the 94th Bishop of Lichfield in 1937. He was born on 1 November 1877, the son of the Revd Frank Woods; his mother, Alice Fry, was a granddaughter of the Quaker prison reformer Elizabeth Fry.

Janet’s mother, Clemence Rachel Barclay (1874-1952), was a daughter of Robert Barclay, a member of a well-known Quaker banking family who lived at High Leigh, near Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire. Clemence Barclay, who was also descended from the abolitionist and social reformer Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton, was born at High Leigh, now a well-known conference centre and regularly the venue for the annual conference of the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel).

High Leigh, once the home of the family of Clemence Barclay, mother of the photographer Janet Stone; Clemence Woods died in Lichfield in 1952 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The Woods family was well-known in church circle: one of Janet’s brothers, Frank Woods, would later become the Archbishop of Melbourne, while another brother, Robin Woods, was Bishop of Worcester. Janet shared the qualities that singled her father out for Church leadership – a good-tempered, gregarious nature, personal magnetism, organising powers and a strong, melodious voice.

Janet Woods and Reynolds Stone were married in Lichfield Cathedral in July 1938. At the time, she was such a fine a soprano that for three months, early in her marriage, she trained as an opera singer under the famous Italian teacher Miele. He gave her free lessons because he believed she was better equipped to sing Verdi than anyone he had ever met.

But the training separated her too much from her husband and her household, which had become the centre of her life. Her decision to give up her musical career was a loss to opera but not to British cultural life.

Janet and Reynolds Stone lived at the Old Rectory in the village of Litton Cheney, close to Chesil Beach in Dorset, for 26 years. There, her creative energies went into making a perfect environment where some of the best British artists and writers came to work and to relax.

Their circle drew in many clever and talented people and led to some notable collaborations, including his illustrations for a selection of Benjamin Britten’s songs, his dust-jackets for the books of Iris Murdoch and Cecil Day Lewis and his watercolours and engravings for Another Self and Ancestral Voices by James Lees-Milne. The stream of guests in summer brought Reynolds a large number of close friendships.

Other people in that circle included Sidney Nolan, LP Hartley, Henry Moore and Frances Partridge.

She worked almost entirely in black-and-white. Most of her best portraits were taken at Litton Cheney, with one of her three cameras, a Canon, a Yashica and an old Rolleiflex, the product of hours of patient observation. Some are said to have an extraordinary spiritual depth – such as those of Iris Murdoch, David Jones and, of course, John Piper.

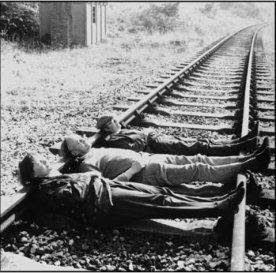

She took beautiful photographs of her four children in their childhood and youth. Humour runs through many of her photographs: Iris Murdoch’s husband, John Bayley (1925-2015), Professor of English Literature at Oxford, is seen lying happily asleep on a railway line; she photographed John Sparrow (1906-1992), Warden of All Souls’ College, Oxford, reading absorbedly with a tea-cosy on his head.

Janet’s mother, Clemence Rachel (Barclay) Woods, died in Lichfield on 14 October 1952; her father, Bishop Edward Woods, died in Lichfield three months later on 11 January 1953. He is commemorated in Lichfield Cathedral by a bust, the work of Jacob Epstein (1958).

After her husband died in 1979, Janet Stone gave up the house and entertaining at Litton Cheney. She died in Salisbury, Wiltshire, on 30 January 1998.

Her life with Reynolds Stone and their home are commemorated in her photographs. Some of these photographs were published in her Thinking Faces (1988). Others were commissioned for books and magazines. She took the author portrait for Kenneth Clark’s book Civilisation (1969), based on his television series. A collection of her prints is now in the archive of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Reynolds Stone was born at Eton on 13 March 1909, where both his father and grandfather were house masters. He read history at Magdalene College Cambridge. During an unofficial apprentice at the Cambridge University Press with Walter Lewis, he began experimenting with engraving on metal and wood. A chance meeting on a train from London to Cambridge with Eric Gill brought an invitation to stay at Gill’s house at Pigotts. There he engraved an alphabet under Gill’s supervision.

His many commissions included engraving his first royal bookplate for the future Queen Mother and headings for the Nonesuch Shakespeare. He was commissioned to engrave the royal arms for the order of service for the coronation of King George VI in 1937, but he was late, and the order of service went to press with an inferior design. However, the reprint contained Stone’s engraving.

He married Janet Woods in Lichfield in 1938, and they first moved to Bucklebury, Berkshire. At this time, he illustrated Rousseau’s Confessions for the Nonesuch Press and The Praise and Happinesse of the Countrie-Life for the Gregynog Press.

He taught himself to cut letters in stone in 1939. During World War II, he worked as an aerial photographic interpreter for the RAF, and he continued to engrave.

Janet and Reynolds Stone moved to the Old Rectory in Litton Cheney in 1953, and he was made CBE that year.

Reynolds engraved the clock device, the court circular, and the royal arms headings for The Times. Other engravings included the royal arms for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, and the coat of arms still seen on the British passport.

He engraved hundreds of bookplates, including those of Benjamin Britten, Peter Pears and Prince Charles, designed the 3d Victory Stamp (1946), and the £5 and £10 notes that were in use until decimalisation. His many memorials in stone and slate include those of Winston Churchill, Ralph Vaughan Williams and TS Eliot in Westminster Abbey.

He illustrated many books, but his magnum opus is the set of engravings, The Old Rectory (1976), published by Warren Editions. His last works included engraved illustrations for A Year of Birds, with poems by Iris Murdoch.

He died on 23 June 1979.

In her memorial address, Iris Murdoch said: ‘Good art shows us reality, which we too rarely see because it is veiled by our selfish cares, anxiety, vanity, pretension. Reynolds as artist, and as man, was a totally unpretentious being. His work, seemingly simple, gives to us that shock of beauty which shows how close, how in a sense ordinary, are the marvels of the world.’

Reynolds Stone, Iris Murdoch and John Bayley … a photograph by Janet Stone

22 December 2021

Praying in Advent 2021:

25, Fyodor Dostoevsky

Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881) by Vasily Perov … Dostoevsky faced a firing squad on 22 December 1849

Patrick Comerford

We are in the final days week of Advent, and there are Christmas sermon, the details of Christmas services to finalise, and Home Communions to organise. Today (22 December2021) is going to be a busy day, but before this busy day begins, I am taking some time early this morning for prayer, reflection and reading.

Each morning in my Advent calendar this year, I have been reflecting in these ways:

1, Reflections on a saint remembered in the calendars of the Church during Advent;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

There is no commemoration in the Church Calendar today [21 December]. But this morning I am reflecting on the life and work of the great Russian writer Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (1821-1881), who was born 200 years ago in 1821, died 140 years ago in 1881, and who has inspired the work and writings of many great theologians.

Dostoevsky’s literary works explore the human condition in the troubled political, social, and spiritual atmospheres of 19th-century Russia, and engage with a variety of philosophical and religious themes. His best-known novels include Crime and Punishment (1866), The Idiot (1869), Demons (1872), and The Brothers Karamazov (1880).

Many regard him as one of the greatest novelists in all of literature, and he is also regarded as a philosopher and the theologian. His work includes some of the most influential literary masterpieces. Notes from Underground (1864) is one of the first works of existentialist literature.

The former Archbishop of Canterbury, Archbishop Rowan Williams, writing in the current edition of The New Statesman (10 December 2021 to 6 January 2022), honestly discusses Dostoevsky’s many ambiguities and weaknesses, including his ‘prejudices and obsessions’ which remain ‘repugnant.’ Yet, he says, Dostoevsky ‘does not have to be a saint or an infallible moral guide’ for us to see the significance of his legacy at the present time.

Dostoevsky was born in Moscow on 11 November 1821 into a Russian Orthodox family of noble ancestry that included many priests, while his father was a military doctor. After graduating, he worked as an engineer and briefly enjoyed a lavish lifestyle, translating books to earn extra money. He wrote his first novel, Poor Folk, in the mid-1840s.

He was arrested in 1849 as part of a literary group that discussed banned books critical of Tsarist Russia. He was sentenced to death, and on this day, 22 December 1849, he and his friends were paraded before a firing squad. Then, as Rowan Williams describes, ‘in a piece of sadistic official theatre, their reprieve was announced at the very last moment.’

His death sentence was commuted, and he spent four years in a Siberian labour camp, followed by six years of compulsory military service in exile. The trauma haunts of almost-execution haunts many pages of his work, and his experience in the prison camp was what Archbishop Williams describes as ‘the seedbed of the most formidable changes in his thinking and sensibility.’

Shortly after his release from prison, Dostoevsky wrote to Natalya Fonvizinia in 1854, ‘If someone were to prove to me that Christ was outside the truth, and it was really the case that the truth lay outside Christ, then I should choose to stay with Christ rather than with the truth.’

In the years that followed years, he worked as a journalist, publishing and editing several magazines and later A Writer’s Diary. He began to travel around western Europe and he developed a gambling addiction that led to financial hardship. For a time, he had to beg for money, but he became the greatst of Russian writers.

His writings influenced a great number of later writers including Russians such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Anton Chekhov, the philosophers Friedrich Nietzsche and Jean-Paul Sartre, theologians from Karl Barth to Rowan Williams, and the emergence of Existentialism.

Dostoevsky’s work is profoundly and explicitly religious, framed in the context of his deep Russian Orthodox faith. By the time of his death, he had developed a unique approach to theology, religious anthropology, and spirituality that continues to exert a profound influence on the Orthodox Church and the Christian world more broadly. He has been described as ‘a prophet forewarned of the politicised humanistic delusions of the 20th century: a prophet crying out in the wilderness.’

His dying wish was to have the Parable of the Prodigal Son be read to his children. The profound meaning of this request is pointed out by Joseph Frank in his biography of Dostoevsky: ‘It was this parable of transgression, repentance, and forgiveness that he wished to leave as a last heritage to his children, and it may well be seen as his own ultimate understanding of the meaning of his life and the message of his work.’

Among Dostoevsky's last words was his quotation of Matthew 3: 14-15: ‘John would have prevented him, saying, “I need to be baptized by you, and do you come to me?” But Jesus answered him, “Let it be so now; for it is proper for us in this way to fulfil all righteousness.” Then he consented.’

He died on 9 February 1881 and was buried in the Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Convent. His gravestone is inscribed with lines from Saint John’s Gospel: ‘Very truly, I tell you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain; but if it dies, it bears much fruit’ (John 12: 24).

His largest work, The Brothers Karamazov, is his magnum opus. It tells the story of the novice Alyosha Karamazov, the non-believer Ivan Karamazov, and the soldier Dmitri Karamazov.

The most famous chapter is ‘The Grand Inquisitor,’ a parable told by Ivan to Alyosha about Christ’s Second Coming in Seville, where Christ is imprisoned by a 90-year-old Grand Inquisitor. Instead of answering the Inquisitor, Christ gives him a kiss, and the Inquisitor subsequently releases him, telling him not to return. Most contemporary critics and scholars agree that Dostoevsky is attacking socialist atheism, represented by the Inquisitor.

The former Archbishop of Canterbury, Archbishop Rowan Williams, took three months off to write his comprehensive book on Dostoevsky’s faith and influence on theology in Dostoevsky: Language, Faith and Fiction (Continuum 2009). In the current edition of The New Statesman, Archbishop Williams, Dostoevsky’s work point to the ‘signs of the transcendent divine stranger whose voice summons everything and everyone into existence.’

Luke 1: 46-56 (NRSVA):

46 And Mary said,

‘My soul magnifies the Lord,

47 and my spirit rejoices in God my Saviour,

48 for he has looked with favour on the lowliness of his servant.

Surely, from now on all generations will call me blessed;

49 for the Mighty One has done great things for me,

and holy is his name.

50 His mercy is for those who fear him

from generation to generation.

51 He has shown strength with his arm;

he has scattered the proud in the thoughts of their hearts.

52 He has brought down the powerful from their thrones,

and lifted up the lowly;

53 he has filled the hungry with good things,

and sent the rich away empty.

54 He has helped his servant Israel,

in remembrance of his mercy,

55 according to the promise he made to our ancestors,

to Abraham and to his descendants for ever.’

56 And Mary remained with her for about three months and then returned to her home.

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (22 December 2021) invites us to pray:

We pray for the Anglican Council of Zimbabwe and the work they are doing to reduce stigma around HIV/AIDS.

Yesterday: Saint Thomas the Apostle

Tomorrow: Archbishop Frederick Temple

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Patrick Comerford

We are in the final days week of Advent, and there are Christmas sermon, the details of Christmas services to finalise, and Home Communions to organise. Today (22 December2021) is going to be a busy day, but before this busy day begins, I am taking some time early this morning for prayer, reflection and reading.

Each morning in my Advent calendar this year, I have been reflecting in these ways:

1, Reflections on a saint remembered in the calendars of the Church during Advent;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

There is no commemoration in the Church Calendar today [21 December]. But this morning I am reflecting on the life and work of the great Russian writer Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (1821-1881), who was born 200 years ago in 1821, died 140 years ago in 1881, and who has inspired the work and writings of many great theologians.

Dostoevsky’s literary works explore the human condition in the troubled political, social, and spiritual atmospheres of 19th-century Russia, and engage with a variety of philosophical and religious themes. His best-known novels include Crime and Punishment (1866), The Idiot (1869), Demons (1872), and The Brothers Karamazov (1880).

Many regard him as one of the greatest novelists in all of literature, and he is also regarded as a philosopher and the theologian. His work includes some of the most influential literary masterpieces. Notes from Underground (1864) is one of the first works of existentialist literature.

The former Archbishop of Canterbury, Archbishop Rowan Williams, writing in the current edition of The New Statesman (10 December 2021 to 6 January 2022), honestly discusses Dostoevsky’s many ambiguities and weaknesses, including his ‘prejudices and obsessions’ which remain ‘repugnant.’ Yet, he says, Dostoevsky ‘does not have to be a saint or an infallible moral guide’ for us to see the significance of his legacy at the present time.

Dostoevsky was born in Moscow on 11 November 1821 into a Russian Orthodox family of noble ancestry that included many priests, while his father was a military doctor. After graduating, he worked as an engineer and briefly enjoyed a lavish lifestyle, translating books to earn extra money. He wrote his first novel, Poor Folk, in the mid-1840s.

He was arrested in 1849 as part of a literary group that discussed banned books critical of Tsarist Russia. He was sentenced to death, and on this day, 22 December 1849, he and his friends were paraded before a firing squad. Then, as Rowan Williams describes, ‘in a piece of sadistic official theatre, their reprieve was announced at the very last moment.’

His death sentence was commuted, and he spent four years in a Siberian labour camp, followed by six years of compulsory military service in exile. The trauma haunts of almost-execution haunts many pages of his work, and his experience in the prison camp was what Archbishop Williams describes as ‘the seedbed of the most formidable changes in his thinking and sensibility.’

Shortly after his release from prison, Dostoevsky wrote to Natalya Fonvizinia in 1854, ‘If someone were to prove to me that Christ was outside the truth, and it was really the case that the truth lay outside Christ, then I should choose to stay with Christ rather than with the truth.’

In the years that followed years, he worked as a journalist, publishing and editing several magazines and later A Writer’s Diary. He began to travel around western Europe and he developed a gambling addiction that led to financial hardship. For a time, he had to beg for money, but he became the greatst of Russian writers.

His writings influenced a great number of later writers including Russians such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Anton Chekhov, the philosophers Friedrich Nietzsche and Jean-Paul Sartre, theologians from Karl Barth to Rowan Williams, and the emergence of Existentialism.

Dostoevsky’s work is profoundly and explicitly religious, framed in the context of his deep Russian Orthodox faith. By the time of his death, he had developed a unique approach to theology, religious anthropology, and spirituality that continues to exert a profound influence on the Orthodox Church and the Christian world more broadly. He has been described as ‘a prophet forewarned of the politicised humanistic delusions of the 20th century: a prophet crying out in the wilderness.’

His dying wish was to have the Parable of the Prodigal Son be read to his children. The profound meaning of this request is pointed out by Joseph Frank in his biography of Dostoevsky: ‘It was this parable of transgression, repentance, and forgiveness that he wished to leave as a last heritage to his children, and it may well be seen as his own ultimate understanding of the meaning of his life and the message of his work.’

Among Dostoevsky's last words was his quotation of Matthew 3: 14-15: ‘John would have prevented him, saying, “I need to be baptized by you, and do you come to me?” But Jesus answered him, “Let it be so now; for it is proper for us in this way to fulfil all righteousness.” Then he consented.’

He died on 9 February 1881 and was buried in the Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Convent. His gravestone is inscribed with lines from Saint John’s Gospel: ‘Very truly, I tell you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain; but if it dies, it bears much fruit’ (John 12: 24).

His largest work, The Brothers Karamazov, is his magnum opus. It tells the story of the novice Alyosha Karamazov, the non-believer Ivan Karamazov, and the soldier Dmitri Karamazov.

The most famous chapter is ‘The Grand Inquisitor,’ a parable told by Ivan to Alyosha about Christ’s Second Coming in Seville, where Christ is imprisoned by a 90-year-old Grand Inquisitor. Instead of answering the Inquisitor, Christ gives him a kiss, and the Inquisitor subsequently releases him, telling him not to return. Most contemporary critics and scholars agree that Dostoevsky is attacking socialist atheism, represented by the Inquisitor.

The former Archbishop of Canterbury, Archbishop Rowan Williams, took three months off to write his comprehensive book on Dostoevsky’s faith and influence on theology in Dostoevsky: Language, Faith and Fiction (Continuum 2009). In the current edition of The New Statesman, Archbishop Williams, Dostoevsky’s work point to the ‘signs of the transcendent divine stranger whose voice summons everything and everyone into existence.’

Luke 1: 46-56 (NRSVA):

46 And Mary said,

‘My soul magnifies the Lord,

47 and my spirit rejoices in God my Saviour,

48 for he has looked with favour on the lowliness of his servant.

Surely, from now on all generations will call me blessed;

49 for the Mighty One has done great things for me,

and holy is his name.

50 His mercy is for those who fear him

from generation to generation.

51 He has shown strength with his arm;

he has scattered the proud in the thoughts of their hearts.

52 He has brought down the powerful from their thrones,

and lifted up the lowly;

53 he has filled the hungry with good things,

and sent the rich away empty.

54 He has helped his servant Israel,

in remembrance of his mercy,

55 according to the promise he made to our ancestors,

to Abraham and to his descendants for ever.’

56 And Mary remained with her for about three months and then returned to her home.

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (22 December 2021) invites us to pray:

We pray for the Anglican Council of Zimbabwe and the work they are doing to reduce stigma around HIV/AIDS.

Yesterday: Saint Thomas the Apostle

Tomorrow: Archbishop Frederick Temple

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)