‘Every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven … brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old’ (Matthew 13: 52) … newspapers at a kiosk in Rethymnon in Crete (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

We are continuing in Ordinary Time in the Church, and the week began with the Sixth Sunday after Trinity (Trinity VI, 27 July 2025). The calendar of the Church of England in Common Worship today remembers Ignatius of Loyola (1556), founder of the Society of Jesus or Jesuits.

Before today begins, I am taking some quiet time this morning to give thanks, for reflection, prayer and reading in these ways:

1, today’s Gospel reading;

2, a reflection on the Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary;

4, the Collects and Post-Communion prayer of the day.

‘The kingdom of heaven is like a net that was thrown into the sea and caught fish of every kind’ (Matthew 13: 47) … fishing boats and nets by the harbour in Iraklion (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Matthew 13: 47-53 (NRSVA):

[Jesus said:] 47 ‘Again, the kingdom of heaven is like a net that was thrown into the sea and caught fish of every kind; 48 when it was full, they drew it ashore, sat down, and put the good into baskets but threw out the bad. 49 So it will be at the end of the age. The angels will come out and separate the evil from the righteous 50 and throw them into the furnace of fire, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.

51 ‘Have you understood all this?’ They answered, ‘Yes.’ 52 And he said to them, ‘Therefore every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven is like the master of a household who brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old.’ 53 When Jesus had finished these parables, he left that place.

‘When [the net] was full, they drew it ashore, sat down, and put the good [fish] into baskets’ (Matthew 13: 48) … a sign outside a fish shop in Rethymnon (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

This morning’s reflection:

We have more weeping and gnashing of teeth in this morning’s Gospel reading (Matthew 13: 47-53), more separating of the righteous and the evil, and more people being thrown into the furnace of fire.

But we also have some more images of what the kingdom of heaven is like:

• Casting a net into the sea (verse 47);

• Catching an abundance of fish (verse 47);

• Drawing the abundance of fish ashore, and realising there is too much there for personal needs (verse 48);

• Writing about it so that others can enjoy the benefit and rewards of treasures new and old (verse 52).

So there are, perhaps, four or five times as many active images of the kingdom than there are passive images.

And we hear that ‘every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven is like the master of a household who brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old’ (Matthew 13: 52).

When the Revd Stephen Hilliard was leaving The Irish Times to enter full-time parish ministry, the then deputy editor, Ken Gray, joked that he was moving from being a ‘column of the Times’ to being a ‘pillar of the Church.’

Later, when I asked Stephen to define the different challenges of journalism and parish ministry, I was told: ‘In many ways they’re the same. We’re supposed to be comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable.’

Nadine Gordimer, in a lecture in London, once argued that a writer’s highest calling is to bear witness to the evils of conflicts and injustice. But that is the calling of a priest too.

When I was moving from journalism in The Irish Times, another colleague asked me, in a tongue-in-cheek way, whether I was moving from being one of the Scribes to being one of the Pharisees.

In my 30 or more years as a full-time journalist and writer, I had tried to work at the point where faith meets the major concerns of the world.

Since leaving The Irish Times back in 2002, I continue to write regularly in other formats too. My daily blog has been a daily exercise: I continue to write occasionally for The Irish Times, the Wexford People, and for local and church-based newspapers and magazines, as well as contributing regularly to books and journals.

But, just as ministry is never exercised as a personal right but always in communion with the Church, so too journalists and writers never write for themselves, but need to heed the needs of editors and readers.

There is a time to be silent in ministry, and there is a time to be silent as a writer. I am humbled whenever I listen to Leonard Cohen’s song, If it be your will. He ended many of his concerts singing this poem, which for me is about submission to God’s will, accepting God’s will, leaving God in control of my spirit. It is a song that I hope is heard at my funeral (later rather than sooner):

If it be your will

That I speak no more

And my voice be still

As it was before

I will speak no more

I shall abide until

I am spoken for

If it be your will

If it be your will

That a voice be true

From this broken hill

I will sing to you

From this broken hill

All your praises they shall ring

If it be your will

To let me sing

From this broken hill

All your praises they shall ring

If it be your will

To let me sing

If it be your will

If there is a choice

Let the rivers fill

Let the hills rejoice

Let your mercy spill

On all these burning hearts in hell

If it be your will

To make us well

And draw us near

And bind us tight

All your children here

In their rags of light

In our rags of light

All dressed to kill

And end this night

If it be your will

If it be your will.

Until then, I shall continue to write.

‘Every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven … brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old’ (Matthew 13: 52) … catching up with the news in ‘The Irish Times’

Today’s Prayers (Thursday 31 July 2025):

The theme this week (27 to 2 August) in Pray with the World Church, the prayer diary of the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel), is ‘Reunited at Last’. This theme was introduced yesterday with a programme update from Raja Moses, Programme Coordinator, Diocese of Durgapur, Church of North India.

The USPG prayer diary today (Thursday 31 July 2025) invites us to pray:

Lord, please strengthen parents and families whose loved ones have been taken. In their darkest moments, give courage, hope and the support they need to bring their children home.

The Collect:

Merciful God,

you have prepared for those who love you

such good things as pass our understanding:

pour into our hearts such love toward you

that we, loving you in all things and above all things,

may obtain your promises,

which exceed all that we can desire;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

Post Communion Prayer:

God of our pilgrimage,

you have led us to the living water:

refresh and sustain us

as we go forward on our journey,

in the name of Jesus Christ our Lord.

Additional Collect:

Creator God,

you made us all in your image:

may we discern you in all that we see,

and serve you in all that we do;

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

‘Every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven … brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old’ (Matthew 13: 52) … newspapers on sale in Athens (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

‘Every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven … brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old’ (Matthew 13: 52)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Showing posts with label Jesuits. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Jesuits. Show all posts

31 July 2025

Daily prayer in Ordinary Time 2025:

83, Thursday 31 July 2025

Labels:

Athens,

boats,

Crete 2025,

Greece 2025,

India,

Iraklion,

Jesuits,

Journalism,

Leonard Cohen,

Mission,

Newspapers,

Prayer,

Rethymnon,

Saint Matthew's Gospel,

The Irish Times,

USPG,

Wexford People,

Writing

22 June 2025

Farm Street Church in

Mayfair, the Jesuit church

displays ‘Gothic Revival

at its most sumptuous’

Inside Farm Street Church or the Church of the Immaculate Conception, the Jesuit-run church in Mayfair, facing the liturgical east end (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Patrick Comerford

When I was in London a few days ago, I visited half or dozen or so churches and chapels in Bloomsbury, Fitzrovia and Mayfair, and for the first time ever visited Farm Street Church or the Church of the Immaculate Conception, the Jesuit-run church in Mayfair.

Farm Street Church and has been described by Sir Simon Jenkins as ‘Gothic Revival at its most sumptuous.’ I cannot explain why I have never visited this church until now, with its interior work by Pugin, Goldie, Salviati and Eric Gill, its stained glass by Hardman of Birmingham, Evie Hone and Patrick Pollen, and its reputation for musical excellence.

Farm Street Church has been well-known for different reasons for over 175 years, including as a community welcoming converts to Roman Catholicism, famous writers, and for challenging preaching and beautiful music and art. Many people have regularly travelled long distances to worship in the church and to seek help and advice from the Jesuit community there.

Farm Street Church was designed by Joseph John Scoles, and his façade was inspired by Beauvais Cathedral (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

When the Jesuits first began looking for a site for a church in London in the 1840s, they found the site in the mews of a back street. The name Farm Street comes from Hay Hill Farm which, in the 18th century, extended from Hill Street east beyond Berkeley Square. Pope Gregory XVI approved building the church in 1843.

The Superior of the English Jesuits at the time was Father Randal Lythgoe. He originally wanted to build a church that could hold 900 people. But this was too expensive, and the church was built with a capacity of 475. It cost £5,800 to build, and this was met by private donations. Father Lythgoe laid the foundation stone in 1844. The church opened for use in 1846 and the church was officially opened by Bishop Nicholas Wiseman, later the first Archbishop of Westminster on 31 July 1849, the feast of the Jesuit founder Saint Ignatius Loyola.

The architect was Joseph John Scoles (1798-1863), who also designed the Church of Saint Francis Xavier, Liverpool, Saint Ignatius Church, Preston, and the Church of Saint James the Less and Saint Helen, Colchester. He was father of Canon Ignatius Scoles, an architect and Jesuit priest, who designed Saint Wilfrid’s Church, Preston, and the church hall at Saint James the Less and Saint Helen, Colchester.

Thomas Jackson was the builder and Henry Taylor Bulmer designed the original interior decorations. Before the official opening, The Builder described the church on 2 June 1849 as ‘a very successful specimen of modern Gothic’.

Inside Farm Street Church, facing the liturgical west, the organ and the rose window (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Because of the limited size of the plot, the church was orientated north-south rather than east-west. The plan of the church is longitudinal, consisting of a nave, aisles with chapels and the sanctuary with side chapels. The overall style is a mixture of Decorated and Flamboyant Gothic, with the west front derived from Beauvais Cathedral, and the east window from Carlisle Cathedral.

The style is Decorated Gothic and Scoles in his design of the façade was inspired by the west front of Beauvais Cathedral. The Caen stone high altar high altar was designed by AWN Pugin, with an inscription requesting prayers for the altar’s benefactor, Monica Tempest. The front panels depict the sacrifices of Abel, Noah, Melchizedek and Abraham. The reredos contains images of the 24 elders in the Book of Revelation (see Revelation 4: 10);

Above Pugin’s high altar are two Venetian mosaic panels by Antonio Salviati (1816-1890) depicting the Annunciation and the Coronation of the Virgin Mary, added in 1875, shortly after Salviati had oepned studios in London. The sanctuary walls are lined with alabaster and marble by George Goldie (1864).

The polychrome statue of Our Lady of Farm Street, by Mayer of Munich, was donated in 1868. The figure is 6 ft high, carved in wood and decorated with gilt in the engraved style.

The words of the Ave Maria (see Luke 1: 26-28) are continued along the upper walls in the church in a series of roundels completed by Filomena Monteiro in 1996.

AWN Pugin’s high altar and the two Venetian mosaic panels by Antonio Salviati (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Originally, the church had a nave, sanctuary with side chapels and only three bays of aisles. Rich furnishings were gradually installed to embellish the church. The side chapels on the south side are dedicated to Saint Aloysius, Saint Joseph and Saint Francis Xavier.

After a fire in the Blessed Sacrament Chapel in 1858, Henry Clutton rebuilt it as the Sacred Heart Chapel (1858-1863), with the assistance of John Francis Bentley (1839-1902), later the architect of Westminster Cathedral. Bentley’s other churches included Holy Rood Church, Watford.

The sanctuary floor was raised in 1864, with the east window raised correspondingly. The side aisles were added as neighbouring land became available. Clutton built the south aisle in 1876-1878, with three chapels and a porch to Farm Street. Alfred Edward Purdie added the red brick presbytery in 1886-1888, and also designed furnishings for several chapels in the 1880s and in 1905.

William Henry Romaine-Walker (1854-1940) built the north aisle in 1898–1903, with five chapels divided by internal buttresses that enclosed confessionals. The chapels and the north aisle continued to be furnished in 1903-1909: the Calvary Chapel, the Altar of the English Martyrs, the Altar of Our Lady and Saint Stanislaus, the Altar of Saint Thomas the Apostle, and the Altar of Our Lady of Sorrows.

The sanctuary walls are lined with alabaster and marble by George Goldie (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

At the same time as the north aisle was built, an additional entrance to Mount Street Gardens was added and the north-east side chapel was reconfigured by Walker as the Chapel of Saint Ignatius. The liturgical east façade became visible and accessible with the demolition of Saint George’s workhouse, which had directly abutted the site boundary, and the laying out of public gardens.

The church was remodelled in 1951 by Adrian Gilbert Scott, following the bomb damage caused during World War II. The church became the parish church of Mayfair in the Diocese of Westminster in 1966 – until then, Baptisms and weddings could not be celebrated in the church.

There were several attempts to reorder the sanctuary without altering AWN Pugin’s high altar. Broadbent, Hastings, Reid & New extended the sanctuary floor in 1980, installed a forward altar, moved the pulpit eastwards to the chancel arch, and removed the altar rail gates to the Calvary Chapel while keeping the rails.

At the same time, the roof was repaired at a cost of over £86,000. In 1987, the roof was painted to a scheme by Austin Winkley. In 1992 a fibreglass cast of Pugin’s high altar was installed as a forward altar, but has since been replaced.

The most recent restoration campaign was completed in 2007 and involved conserving the stonework on the exterior, in the sanctuary and in the Sacred Heart Chapel.

The new altar, solemnly dedicated in 2019, was carved in Carrara marble by Paul Jakeman of London and features a frieze of bunches of grapes, calling to mind the Eucharist.

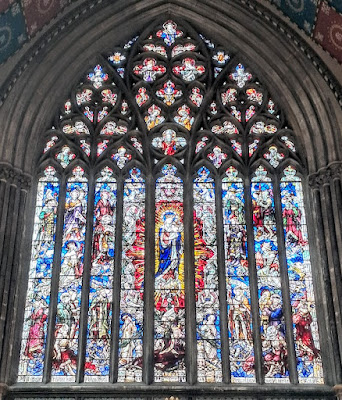

The original East Window was replaced in 1912 by a new window by John Hardman of Birmingham (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

The great window in the chancel at the litrugical east end of the church was based on the east window in Carlisle Cathedral, with the theme of the Jesse Tree, tracing the family tree of Jesus back to the father of King David. The original was tarnished by pollution, and was replaced in 1912 by a new one by John Hardman of Birmingham. The old window was then cleaned and repaired and then moved to Saint Agnes Church in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec.

Hardman modified the original design of the Jesse Tree in the window to make the Madonna with the Christ Child the central figure.

The rose window at the liturgical west end by the Irish artist Evie Hone (1894-1955) depicts the instruments of Christ’s Passion. She also designed the window in the Lourdes Chapel depicting the Assumption. She once had a workshop in the courtyard at Marlay Park in Rathfarnham.

The window in the Calvary Chapel by Patrick Pollen (1928-2010), who worked with Evie Hone and Catherine O’Brien at An Túr Gloine, depicts three Jesuit English martyrs and saints: Edmund Campion, Robert Southwell and Nicholas Owen.

The window by Patrick Pollen depicting three Jesuit English martyrs: Edmund Campion, Robert Southwell and Nicholas Owen (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

In his book England’s Thousand Best Churches (1999), Sir Simon Jenkins says, ‘Not an inch of wall surface is without decoration, and this in the austere 1840s, not the colourful late-Victorian era. The right aisle carries large panels portraying the Stations of the Cross. The left aisle has side chapels and confessionals, ingeniously carved within the piers. In the west window above the gallery is excellent modern glass by Evie Hone of 1953, with the richness of colour of a Burne-Jones.’

The church opened its doors to LGBT Catholics in 2013 after the ‘Soho Masses’ came to an end after six years at the nearby Church of Our Lady of the Assumption and Saint Gregory. Archbishop Vincent Nichols attended the first of these Masses in Farm Street.

The parish also has a focus on service to the disadvantaged, especially the homeless, refugees, trafficked people and people who suffer because of the faith, and supports Jesuit and Catholic projects in the Middle East, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

William Henry Romaine-Walker built the north aisle in 1898–1903, with five chapels divided by internal buttresses (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Farm Street Church has developed a reputation for its music over the years. In the 19th century, the choir consisted only of men and boys drawn from the local Roman Catholic schools.

Between 1881 and 1916, the organist was John Francis Brewer, son of the architectural illustrator Henry William Brewer, who was just 18 when appointed.

After World War I, the choir wasunder the direction of Father John Driscoll and then Fernand Laloux, and the organist was Guy Weitz, a Belgian who had been a pupil of Charles-Marie Widor and Alexandre Guilmant. One of Weitz’s most notable students was Nicholas Danby (1935-1997) who succeeded him as the church organist in 1967. Danby’s main achievement at Farm Street was re-establishing the choir in the early 1970s, following a period of change in the late 1960s, as a fully professional ensemble.

A number of recordings were made of the music at Farm Street church were made in the 1990s. A CD of organ music was recorded at Farm Street in 2000 by David Graham and included the music of Guy Weitz. Today, the repertoire at Farm Street includes 16th century polyphony, the Viennese classical composers, 19th century romantics, 20th century and contemporary music as well as Gregorian chant.

The sanctuary was reordered on several occasions without altering AWN Pugin’s high altar (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

The Mount Street Jesuit Centre was launched in 2004 to provide adult Christian formation through prayer, worship, theological education and social justice. It offers non-residential retreats and courses in spirituality and provides a full-time GP service for homeless people.

When Heythrop College formally closed in 2019, the London Jesuit Centre was launched at the Mount Street Jesuit Centre. It includes a reading room of the Heythrop Library, with access to about 8,000 books and indirect access to most of the collection of Heythrop College. The London Jesuit Centre also provides teaching courses, spirituality, retreats and research. and residential and non-residential retreats.

The Month, a monthly review published by the Jesuits at Farm Street, was founded by Frances Margaret Taylor (1832-1900) in 1864, but closed in 2001. Thinking Faith was launched as an online journal in 2008 and publishes theological papers as well as papers on philosophy, spirituality, the arts, poetry, culture, Biblical studies, political and social issues and current affairs.

King Charles III attended a special Advent service at Farm Street Church organised by Aid to the Church in Need (ACN), a charity that supports persecuted Christians.

• Mass times on Sundays are at 8 am, 9:30 and 11, with a young adults Mass at 7 pm. Weekday Masses, Monday to Friday, are at 8 am, 1:05 pm and 6 pm. Saturday Masses are at 10 am and 6 pm (Saturday Vigil).

The Homeless Jesus, a sculpture in Farm Street Church by Timothy Schmalz (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Stations XIII and XIV in the Stations of the Cross in Farm Street Church (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

The polychrome statue of Our Lady of Farm Street, by Mayer of Munich, was donated in 1868 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

The liturgical east façade facing Mount Street Gardens became accessible with the demolition of Saint George’s workhouse (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Patrick Comerford

When I was in London a few days ago, I visited half or dozen or so churches and chapels in Bloomsbury, Fitzrovia and Mayfair, and for the first time ever visited Farm Street Church or the Church of the Immaculate Conception, the Jesuit-run church in Mayfair.

Farm Street Church and has been described by Sir Simon Jenkins as ‘Gothic Revival at its most sumptuous.’ I cannot explain why I have never visited this church until now, with its interior work by Pugin, Goldie, Salviati and Eric Gill, its stained glass by Hardman of Birmingham, Evie Hone and Patrick Pollen, and its reputation for musical excellence.

Farm Street Church has been well-known for different reasons for over 175 years, including as a community welcoming converts to Roman Catholicism, famous writers, and for challenging preaching and beautiful music and art. Many people have regularly travelled long distances to worship in the church and to seek help and advice from the Jesuit community there.

Farm Street Church was designed by Joseph John Scoles, and his façade was inspired by Beauvais Cathedral (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

When the Jesuits first began looking for a site for a church in London in the 1840s, they found the site in the mews of a back street. The name Farm Street comes from Hay Hill Farm which, in the 18th century, extended from Hill Street east beyond Berkeley Square. Pope Gregory XVI approved building the church in 1843.

The Superior of the English Jesuits at the time was Father Randal Lythgoe. He originally wanted to build a church that could hold 900 people. But this was too expensive, and the church was built with a capacity of 475. It cost £5,800 to build, and this was met by private donations. Father Lythgoe laid the foundation stone in 1844. The church opened for use in 1846 and the church was officially opened by Bishop Nicholas Wiseman, later the first Archbishop of Westminster on 31 July 1849, the feast of the Jesuit founder Saint Ignatius Loyola.

The architect was Joseph John Scoles (1798-1863), who also designed the Church of Saint Francis Xavier, Liverpool, Saint Ignatius Church, Preston, and the Church of Saint James the Less and Saint Helen, Colchester. He was father of Canon Ignatius Scoles, an architect and Jesuit priest, who designed Saint Wilfrid’s Church, Preston, and the church hall at Saint James the Less and Saint Helen, Colchester.

Thomas Jackson was the builder and Henry Taylor Bulmer designed the original interior decorations. Before the official opening, The Builder described the church on 2 June 1849 as ‘a very successful specimen of modern Gothic’.

Inside Farm Street Church, facing the liturgical west, the organ and the rose window (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Because of the limited size of the plot, the church was orientated north-south rather than east-west. The plan of the church is longitudinal, consisting of a nave, aisles with chapels and the sanctuary with side chapels. The overall style is a mixture of Decorated and Flamboyant Gothic, with the west front derived from Beauvais Cathedral, and the east window from Carlisle Cathedral.

The style is Decorated Gothic and Scoles in his design of the façade was inspired by the west front of Beauvais Cathedral. The Caen stone high altar high altar was designed by AWN Pugin, with an inscription requesting prayers for the altar’s benefactor, Monica Tempest. The front panels depict the sacrifices of Abel, Noah, Melchizedek and Abraham. The reredos contains images of the 24 elders in the Book of Revelation (see Revelation 4: 10);

Above Pugin’s high altar are two Venetian mosaic panels by Antonio Salviati (1816-1890) depicting the Annunciation and the Coronation of the Virgin Mary, added in 1875, shortly after Salviati had oepned studios in London. The sanctuary walls are lined with alabaster and marble by George Goldie (1864).

The polychrome statue of Our Lady of Farm Street, by Mayer of Munich, was donated in 1868. The figure is 6 ft high, carved in wood and decorated with gilt in the engraved style.

The words of the Ave Maria (see Luke 1: 26-28) are continued along the upper walls in the church in a series of roundels completed by Filomena Monteiro in 1996.

AWN Pugin’s high altar and the two Venetian mosaic panels by Antonio Salviati (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Originally, the church had a nave, sanctuary with side chapels and only three bays of aisles. Rich furnishings were gradually installed to embellish the church. The side chapels on the south side are dedicated to Saint Aloysius, Saint Joseph and Saint Francis Xavier.

After a fire in the Blessed Sacrament Chapel in 1858, Henry Clutton rebuilt it as the Sacred Heart Chapel (1858-1863), with the assistance of John Francis Bentley (1839-1902), later the architect of Westminster Cathedral. Bentley’s other churches included Holy Rood Church, Watford.

The sanctuary floor was raised in 1864, with the east window raised correspondingly. The side aisles were added as neighbouring land became available. Clutton built the south aisle in 1876-1878, with three chapels and a porch to Farm Street. Alfred Edward Purdie added the red brick presbytery in 1886-1888, and also designed furnishings for several chapels in the 1880s and in 1905.

William Henry Romaine-Walker (1854-1940) built the north aisle in 1898–1903, with five chapels divided by internal buttresses that enclosed confessionals. The chapels and the north aisle continued to be furnished in 1903-1909: the Calvary Chapel, the Altar of the English Martyrs, the Altar of Our Lady and Saint Stanislaus, the Altar of Saint Thomas the Apostle, and the Altar of Our Lady of Sorrows.

The sanctuary walls are lined with alabaster and marble by George Goldie (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

At the same time as the north aisle was built, an additional entrance to Mount Street Gardens was added and the north-east side chapel was reconfigured by Walker as the Chapel of Saint Ignatius. The liturgical east façade became visible and accessible with the demolition of Saint George’s workhouse, which had directly abutted the site boundary, and the laying out of public gardens.

The church was remodelled in 1951 by Adrian Gilbert Scott, following the bomb damage caused during World War II. The church became the parish church of Mayfair in the Diocese of Westminster in 1966 – until then, Baptisms and weddings could not be celebrated in the church.

There were several attempts to reorder the sanctuary without altering AWN Pugin’s high altar. Broadbent, Hastings, Reid & New extended the sanctuary floor in 1980, installed a forward altar, moved the pulpit eastwards to the chancel arch, and removed the altar rail gates to the Calvary Chapel while keeping the rails.

At the same time, the roof was repaired at a cost of over £86,000. In 1987, the roof was painted to a scheme by Austin Winkley. In 1992 a fibreglass cast of Pugin’s high altar was installed as a forward altar, but has since been replaced.

The most recent restoration campaign was completed in 2007 and involved conserving the stonework on the exterior, in the sanctuary and in the Sacred Heart Chapel.

The new altar, solemnly dedicated in 2019, was carved in Carrara marble by Paul Jakeman of London and features a frieze of bunches of grapes, calling to mind the Eucharist.

The original East Window was replaced in 1912 by a new window by John Hardman of Birmingham (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

The great window in the chancel at the litrugical east end of the church was based on the east window in Carlisle Cathedral, with the theme of the Jesse Tree, tracing the family tree of Jesus back to the father of King David. The original was tarnished by pollution, and was replaced in 1912 by a new one by John Hardman of Birmingham. The old window was then cleaned and repaired and then moved to Saint Agnes Church in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec.

Hardman modified the original design of the Jesse Tree in the window to make the Madonna with the Christ Child the central figure.

The rose window at the liturgical west end by the Irish artist Evie Hone (1894-1955) depicts the instruments of Christ’s Passion. She also designed the window in the Lourdes Chapel depicting the Assumption. She once had a workshop in the courtyard at Marlay Park in Rathfarnham.

The window in the Calvary Chapel by Patrick Pollen (1928-2010), who worked with Evie Hone and Catherine O’Brien at An Túr Gloine, depicts three Jesuit English martyrs and saints: Edmund Campion, Robert Southwell and Nicholas Owen.

The window by Patrick Pollen depicting three Jesuit English martyrs: Edmund Campion, Robert Southwell and Nicholas Owen (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

In his book England’s Thousand Best Churches (1999), Sir Simon Jenkins says, ‘Not an inch of wall surface is without decoration, and this in the austere 1840s, not the colourful late-Victorian era. The right aisle carries large panels portraying the Stations of the Cross. The left aisle has side chapels and confessionals, ingeniously carved within the piers. In the west window above the gallery is excellent modern glass by Evie Hone of 1953, with the richness of colour of a Burne-Jones.’

The church opened its doors to LGBT Catholics in 2013 after the ‘Soho Masses’ came to an end after six years at the nearby Church of Our Lady of the Assumption and Saint Gregory. Archbishop Vincent Nichols attended the first of these Masses in Farm Street.

The parish also has a focus on service to the disadvantaged, especially the homeless, refugees, trafficked people and people who suffer because of the faith, and supports Jesuit and Catholic projects in the Middle East, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

William Henry Romaine-Walker built the north aisle in 1898–1903, with five chapels divided by internal buttresses (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Farm Street Church has developed a reputation for its music over the years. In the 19th century, the choir consisted only of men and boys drawn from the local Roman Catholic schools.

Between 1881 and 1916, the organist was John Francis Brewer, son of the architectural illustrator Henry William Brewer, who was just 18 when appointed.

After World War I, the choir wasunder the direction of Father John Driscoll and then Fernand Laloux, and the organist was Guy Weitz, a Belgian who had been a pupil of Charles-Marie Widor and Alexandre Guilmant. One of Weitz’s most notable students was Nicholas Danby (1935-1997) who succeeded him as the church organist in 1967. Danby’s main achievement at Farm Street was re-establishing the choir in the early 1970s, following a period of change in the late 1960s, as a fully professional ensemble.

A number of recordings were made of the music at Farm Street church were made in the 1990s. A CD of organ music was recorded at Farm Street in 2000 by David Graham and included the music of Guy Weitz. Today, the repertoire at Farm Street includes 16th century polyphony, the Viennese classical composers, 19th century romantics, 20th century and contemporary music as well as Gregorian chant.

The sanctuary was reordered on several occasions without altering AWN Pugin’s high altar (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

The Mount Street Jesuit Centre was launched in 2004 to provide adult Christian formation through prayer, worship, theological education and social justice. It offers non-residential retreats and courses in spirituality and provides a full-time GP service for homeless people.

When Heythrop College formally closed in 2019, the London Jesuit Centre was launched at the Mount Street Jesuit Centre. It includes a reading room of the Heythrop Library, with access to about 8,000 books and indirect access to most of the collection of Heythrop College. The London Jesuit Centre also provides teaching courses, spirituality, retreats and research. and residential and non-residential retreats.

The Month, a monthly review published by the Jesuits at Farm Street, was founded by Frances Margaret Taylor (1832-1900) in 1864, but closed in 2001. Thinking Faith was launched as an online journal in 2008 and publishes theological papers as well as papers on philosophy, spirituality, the arts, poetry, culture, Biblical studies, political and social issues and current affairs.

King Charles III attended a special Advent service at Farm Street Church organised by Aid to the Church in Need (ACN), a charity that supports persecuted Christians.

• Mass times on Sundays are at 8 am, 9:30 and 11, with a young adults Mass at 7 pm. Weekday Masses, Monday to Friday, are at 8 am, 1:05 pm and 6 pm. Saturday Masses are at 10 am and 6 pm (Saturday Vigil).

The Homeless Jesus, a sculpture in Farm Street Church by Timothy Schmalz (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Stations XIII and XIV in the Stations of the Cross in Farm Street Church (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

The polychrome statue of Our Lady of Farm Street, by Mayer of Munich, was donated in 1868 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

The liturgical east façade facing Mount Street Gardens became accessible with the demolition of Saint George’s workhouse (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

22 April 2025

Saint Mary Major, where

Pope Francis is being

buried, is one of the Papal

basilicas in Rome

The Basilica of Saint Mary Major … Pope Francis is to be buried there on Saturday (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

Pope Francis is to be buried in the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore or the Basilica of Saint Mary Major in Rome after his funeral in Saint Peter’s Basilica on Saturday. Pope Francis had long made the arrangements for his funeral and, despite some media comments, Saint Mary Major is not so unusual a choice for his funeral.

The high altar, by tradition, is reserved for Mass celebrated by the Pope, who is the archpriest of the basilica, and it is the burial place of a number of previous popes, Pope Sixtus V and Pope Pius V. The crypt is the burial place of Saint Jerome, who translated the Bible into Latin. It is also an appropriate place for the burial of the first Jesuit Pope: after his ordination as a priest, Saint Ignatius of Loyola celebrated his first Mass there on 25 December 1538.

Saint Mary Major is also the largest church in Rome dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Of all the great churches in Rome, it has the most successful blend of different architectural styles, and has magnificent mosaics.

Saint Mary Major contains a successful blend of different architectural styles (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore or Basilica of Saint Mary Major is a Papal basilica, along with Saint John Lateran, Saint Peter’s, and Saint Paul outside the Walls.

Under the Lateran Treaty signed in 1929 by the Holy See and Italy, Saint Mary Major stands on Italian sovereign territory and not the territory of the Vatican City State. However, the Vatican fully owns the basilica, and in Italian law it enjoys full diplomatic immunity.

This ancient basilica enshrines the image of Salus Populi Romani, depicting the Virgin Mary as the protector of the Roman people.

The Basilica is sometimes known as Our Lady of the Snows, with a feast day on 5 August. The church has also been called Saint Mary of the Crib because of a relic of the crib or Bethlehem brought to the church in the time of Pope Theodore I (640-649).

A popular story says that during the reign of Pope Liberius, a Roman patrician named John and his wife, who had no heirs and decided to donate their possessions to the Virgin Mary. They prayed about how to hand over their property, and on the night of 5 August, at the height of summer, snow fell on the summit of the Esquiline Hill. That night, this childless couple resolved to build a basilica in honour of the Virgin Mary on the place that was covered in snow.

However, this story only dates from the 14th century and has no historical basis. Even in the early 13th century, a tradition had common currency that Pope Liberius had built the basilica in his own name, and for long it was known as the Liberian Basilica. The feast of the dedication was inserted for the first time into the General Roman Calendar as late as 1568.

But the legend of the snowfall and the bequest it inspired is still commemorated each year on 5 August when white rose petals are dropped from the dome during Mass and the Second Vespers of the feast.

The canopied high altar in Saint Mary Major is reserved for Mass said by the Pope (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Despite appearances, the earliest building on the site was the Liberian Basilica or Santa Maria Liberiana, named after Pope Liberius (352-366). It is said Pope Liberius transformed a palace of the Sicinini family into a church, which was known as the Sicinini Basilica.

A century later, Pope Sixtus III (432-440) replaced this first church with a new church dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Santa Maria Maggiore, one of the first churches built in honour of the Virgin Mary, was built in the immediate aftermath of the Council of Ephesus in 431, which proclaimed the Virgin Mary the Mother of God.

The present church retains the core of this structure, despite several later building projects and damage caused by an earthquake in 1348, and Saint Mary Major was restored, redecorated and extended by successive popes, including Eugene III (1145-1153), Nicholas IV (1288-1292), Clement X (1670-1676), and Benedict XIV (1740-1758).

When the Popes returned to Rome after the papal exile in Avignon, the Lateran Palace was in such a sad state of disrepair, and Saint Mary Major and its buildings provided a temporary Palace for the Popes. Later they moved to the Palace of the Vatican on the other side of the River Tiber.

Between 1575 and 1630, the interior of Santa Maria Maggiore underwent a broad renovation encompassing all its altars. In the 1740s, Pope Benedict XIV commissioned Ferdinando Fuga to build the present façade and to modify the interior. The 12th-century façade was masked during this rebuilding project, with a screening loggia added in 1743. However, Fuga did not damage the mosaics of the façade.

Although Saint Mary Major is immense in area, it was built to plan. The design of the basilica was typical for Rome at that time. It has a tall and wide nave, an aisle on either side. and a semi-circular apse at the end of the nave, with beautiful mosaics on the triumphal arch and nave.

The Athenian marble columns supporting the nave may have come from the first basilica, or from another antique Roman building. They include 36 marble and four granite columns that were pared down or shortened to make them identical by Ferdinando Fuga, who provided them with identical gilt-bronze capitals.

The 16th century coffered ceiling, designed by Giuliano da Sangallo, is said to be gilded with the first gold brought back from the Americas by Christopher Columbus and presented by Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain to Pope Alexander VI.

The canopied high altar is reserved for Mass said by the Pope, the basilica’s archpriest and a small number of priests. Customarily, the Pope celebrates Mass there each year on the feast of the Assumption (15 August). Pope Francis visited Saint Mary Major a day after his election.

The Coronation of Mary depicted in the apse mosaic (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The unique treasure in Saint Mary Major must be the fifth century mosaics, commissioned by Pope Sixtus III. The mosaics include some of the oldest depictions of the Virgin Mary in Christian art, celebrating the declaration of her as the Theotokos or Mother of God at the Council of Ephesus in 431. The nave mosaics recount four cycles of sacred history featuring Abraham, Jacob, Moses and Joshua; seen together, they tell of God’s promise to the Jewish people and his assistance as they strive to reach it.

The story, which is not told in chronological order, starts on the left-hand wall near the triumphal arch with the Sacrifice of Melchisedek. The next scenes illustrate earlier episodes from the life of Abraham. The stories continue with Jacob, with whom God renews the promise made to Abraham, Moses, who liberates the people from slavery, and Joshua, who leads them into the Promised Land.

The journey concludes with the two final panels. These frescoes date from the restoration commissioned by Cardinal Pinelli and show David leading the Ark of the Covenant into Jerusalem and the Temple of Jerusalem built by Solomon.

Christ’s childhood, as told in apocryphal Gospels, is illustrated in four images in the triumphal arch. The first, in the upper left, shows the Annunciation, with the Virgin Mary robed like a Roman princess. The story continues with the Annunciation to Joseph, the Adoration of the Magi and the Massacre of the Innocents. The upper right illustrates the Presentation in the Temple, the Flight into Egypt and the meeting between the Holy Family and the Governor of Sotine. The last scene represents the Magi before Herod.

At the bottom of the arch, Bethlehem is depicted on the left and Jerusalem on the right. Between these scenes, the empty throne waiting for the Second Coming is flanked by Saint Peter and Saint Paul. Together they will form the church of which Peter is the leader, and Sixtus III is his successor.

In the 13th century, Pope Nicholas IV, the first Franciscan pope, decided to destroy the old apse and build the present one, placing it several meters back in order to create a transept for the choir between the arch and the apse. The decoration of the apse is the work of the Franciscan friar Jacopo Torriti, and the work was paid for by Cardinals Giacomo and Pietro Colonna.

Torriti’s mosaic, dating from 1295, is divided into two parts. The central medallion in the apse shows the Coronation of the Virgin Mary, while the lower band illustrates the most important moments of her life. In the centre of the medallion, enclosed by concentric circles, Christ and Mary are seated on a large oriental throne. Christ is enthroned like a young emperor and he is placing a jewelled crown on her head; she is dressed in a colourful veil, like a Roman empress. The sun, the moon and a choir of angels are arranged around their feet, while Saint Peter, Saint Paul, and Saint Francis of Assisi along with Pope Nicholas IV flank them on the left. On the right, Torriti portrays Saint John the Baptist, Saint John the Evangelist, Saint Anthony and the donor, Cardinal Colonna.

In the lower apse, mosaic scenes to the left and the right show the life of the Virgin Mary, while the central panel represents the Dormition, telling the story in a way that is typical of Byzantine iconography rather than western narratives. She is lying on a bed, as angels prepare to lift her soul to Heaven, the apostles watch astonished and Christ takes her soul into his arms. Torriti embellishes the scene with two small Franciscan figures and a lay person wearing a 13th century cap.

The Crypt of the Nativity is said to contain wooden relics from the Crib in Bethlehem (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Under the High Altar, the Crypt of the Nativity or Bethlehem Crypt has a crystal reliquary designed by Giuseppe Valadier and said to contain wooden relics from the Crib of the Christ Child in Bethlehem.

The statue in the crypt of Pope Pius IX in prayer is by Ignazio Jacometti, ca 1880, and is over the tomb of Saint Jerome (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The crypt is also the burial place of Saint Jerome, who translated the Bible into Latin or Vulgate version and died in 420. Above his burial place is a kneeling statue of Pope Pius IX, who proclaimed the dogma of the Immaculate Conception on 8 December 1854 and who ordered the reconstruction of the crypt.

In the right transept, the Sistine Chapel or chapel of the Blessed Sacrament, is named after Pope Sixtus V. This chapel, which was designed by Domenico Fontana, includes the tombs of Pope Sixtus V and Pope Pius V. After his ordination as a priest, Saint Ignatius of Loyola celebrated his first Mass in this chapel on 25 December 1538.

Just outside the Sistine Chapel is the tomb of Gian Lorenzo Bernini and his family.

The Assumption of Mary was painted inside the cupola of the Borghese Chapel by Galileo’s friend Ludovico Cardi (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The celebrated icon of the Virgin Mary in the Borghese Chapel is known as Salus Populi Romani, or Health of the Roman People. The icon is said to have saved the people of Rome from the plague. Tradition attributes the icon to Saint Luke the Evangelist, and this richly decorated chapel was designed for Pope Paul V Borghese.

The Assumption of Mary was painted inside the cupola of the chapel by Ludovico Cardi nicknamed Il Cigoli. Above the clouds, the Virgin Mary is seen being transported towards Heaven. The moon beneath her feet is painted as it was seen through the telescope of Galileo, who was a friend of Cigoli.

The floor of the church is paved in opus sectile mosaic, featuring the Borghese heraldic arms of an eagle and a dragon.

The 1995 rose window symbolises the link between the Old Covenant and the New Covenant (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

In 1995, a new, rose window in stained glass was created for the main façade by Giovanni Hajnal. It reaffirms the declaration of the Second Vatican Council that Mary, the exalted daughter of Zion, is the link that unites the Church as the New Covenant to the Old Testament and the Covenant with the Children of Israel. To symbolise the Old Testament, Hajnal used the two tablets of the Ten Commandments and the seven-branched Menorah or candlestick, and for the New Testament he used the Cross, the Host and the Chalice of the Eucharist.

The 14th century campanile or bell tower is the highest in Rome at 75 metres. It was erected by Pope Gregory XI after his return from Avignon.

Outside, the column in Piazza Santa Maria Maggiore came from the Basilica of Constantine in the Forum and was designed by Carlo Maderno. It was erected in 1615 and has since become the model for numerous Marian columns throughout the Catholic world.

The church is served by Redemptorist and Dominican priests. In the portico, there is a fine statue by Bernini and Lucenti of King Philip IV of Spain, one of the benefactors of the church. The King of Spain is ex officio a lay canon of the basilica. In a similar manner, the President of France is ex officio an honorary canon of Saint John Lateran.

The development of the city has taken away the impact of Santa Maria Major’s commanding position on the summit of the Esquiline Hill, but the church is still considered by many to be the most beautiful church in Rome after Saint Peter’s.

Inside the Baptistery in Saint Mary Major (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

Pope Francis is to be buried in the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore or the Basilica of Saint Mary Major in Rome after his funeral in Saint Peter’s Basilica on Saturday. Pope Francis had long made the arrangements for his funeral and, despite some media comments, Saint Mary Major is not so unusual a choice for his funeral.

The high altar, by tradition, is reserved for Mass celebrated by the Pope, who is the archpriest of the basilica, and it is the burial place of a number of previous popes, Pope Sixtus V and Pope Pius V. The crypt is the burial place of Saint Jerome, who translated the Bible into Latin. It is also an appropriate place for the burial of the first Jesuit Pope: after his ordination as a priest, Saint Ignatius of Loyola celebrated his first Mass there on 25 December 1538.

Saint Mary Major is also the largest church in Rome dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Of all the great churches in Rome, it has the most successful blend of different architectural styles, and has magnificent mosaics.

Saint Mary Major contains a successful blend of different architectural styles (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore or Basilica of Saint Mary Major is a Papal basilica, along with Saint John Lateran, Saint Peter’s, and Saint Paul outside the Walls.

Under the Lateran Treaty signed in 1929 by the Holy See and Italy, Saint Mary Major stands on Italian sovereign territory and not the territory of the Vatican City State. However, the Vatican fully owns the basilica, and in Italian law it enjoys full diplomatic immunity.

This ancient basilica enshrines the image of Salus Populi Romani, depicting the Virgin Mary as the protector of the Roman people.

The Basilica is sometimes known as Our Lady of the Snows, with a feast day on 5 August. The church has also been called Saint Mary of the Crib because of a relic of the crib or Bethlehem brought to the church in the time of Pope Theodore I (640-649).

A popular story says that during the reign of Pope Liberius, a Roman patrician named John and his wife, who had no heirs and decided to donate their possessions to the Virgin Mary. They prayed about how to hand over their property, and on the night of 5 August, at the height of summer, snow fell on the summit of the Esquiline Hill. That night, this childless couple resolved to build a basilica in honour of the Virgin Mary on the place that was covered in snow.

However, this story only dates from the 14th century and has no historical basis. Even in the early 13th century, a tradition had common currency that Pope Liberius had built the basilica in his own name, and for long it was known as the Liberian Basilica. The feast of the dedication was inserted for the first time into the General Roman Calendar as late as 1568.

But the legend of the snowfall and the bequest it inspired is still commemorated each year on 5 August when white rose petals are dropped from the dome during Mass and the Second Vespers of the feast.

The canopied high altar in Saint Mary Major is reserved for Mass said by the Pope (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Despite appearances, the earliest building on the site was the Liberian Basilica or Santa Maria Liberiana, named after Pope Liberius (352-366). It is said Pope Liberius transformed a palace of the Sicinini family into a church, which was known as the Sicinini Basilica.

A century later, Pope Sixtus III (432-440) replaced this first church with a new church dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Santa Maria Maggiore, one of the first churches built in honour of the Virgin Mary, was built in the immediate aftermath of the Council of Ephesus in 431, which proclaimed the Virgin Mary the Mother of God.

The present church retains the core of this structure, despite several later building projects and damage caused by an earthquake in 1348, and Saint Mary Major was restored, redecorated and extended by successive popes, including Eugene III (1145-1153), Nicholas IV (1288-1292), Clement X (1670-1676), and Benedict XIV (1740-1758).

When the Popes returned to Rome after the papal exile in Avignon, the Lateran Palace was in such a sad state of disrepair, and Saint Mary Major and its buildings provided a temporary Palace for the Popes. Later they moved to the Palace of the Vatican on the other side of the River Tiber.

Between 1575 and 1630, the interior of Santa Maria Maggiore underwent a broad renovation encompassing all its altars. In the 1740s, Pope Benedict XIV commissioned Ferdinando Fuga to build the present façade and to modify the interior. The 12th-century façade was masked during this rebuilding project, with a screening loggia added in 1743. However, Fuga did not damage the mosaics of the façade.

Although Saint Mary Major is immense in area, it was built to plan. The design of the basilica was typical for Rome at that time. It has a tall and wide nave, an aisle on either side. and a semi-circular apse at the end of the nave, with beautiful mosaics on the triumphal arch and nave.

The Athenian marble columns supporting the nave may have come from the first basilica, or from another antique Roman building. They include 36 marble and four granite columns that were pared down or shortened to make them identical by Ferdinando Fuga, who provided them with identical gilt-bronze capitals.

The 16th century coffered ceiling, designed by Giuliano da Sangallo, is said to be gilded with the first gold brought back from the Americas by Christopher Columbus and presented by Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain to Pope Alexander VI.

The canopied high altar is reserved for Mass said by the Pope, the basilica’s archpriest and a small number of priests. Customarily, the Pope celebrates Mass there each year on the feast of the Assumption (15 August). Pope Francis visited Saint Mary Major a day after his election.

The Coronation of Mary depicted in the apse mosaic (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The unique treasure in Saint Mary Major must be the fifth century mosaics, commissioned by Pope Sixtus III. The mosaics include some of the oldest depictions of the Virgin Mary in Christian art, celebrating the declaration of her as the Theotokos or Mother of God at the Council of Ephesus in 431. The nave mosaics recount four cycles of sacred history featuring Abraham, Jacob, Moses and Joshua; seen together, they tell of God’s promise to the Jewish people and his assistance as they strive to reach it.

The story, which is not told in chronological order, starts on the left-hand wall near the triumphal arch with the Sacrifice of Melchisedek. The next scenes illustrate earlier episodes from the life of Abraham. The stories continue with Jacob, with whom God renews the promise made to Abraham, Moses, who liberates the people from slavery, and Joshua, who leads them into the Promised Land.

The journey concludes with the two final panels. These frescoes date from the restoration commissioned by Cardinal Pinelli and show David leading the Ark of the Covenant into Jerusalem and the Temple of Jerusalem built by Solomon.

Christ’s childhood, as told in apocryphal Gospels, is illustrated in four images in the triumphal arch. The first, in the upper left, shows the Annunciation, with the Virgin Mary robed like a Roman princess. The story continues with the Annunciation to Joseph, the Adoration of the Magi and the Massacre of the Innocents. The upper right illustrates the Presentation in the Temple, the Flight into Egypt and the meeting between the Holy Family and the Governor of Sotine. The last scene represents the Magi before Herod.

At the bottom of the arch, Bethlehem is depicted on the left and Jerusalem on the right. Between these scenes, the empty throne waiting for the Second Coming is flanked by Saint Peter and Saint Paul. Together they will form the church of which Peter is the leader, and Sixtus III is his successor.

In the 13th century, Pope Nicholas IV, the first Franciscan pope, decided to destroy the old apse and build the present one, placing it several meters back in order to create a transept for the choir between the arch and the apse. The decoration of the apse is the work of the Franciscan friar Jacopo Torriti, and the work was paid for by Cardinals Giacomo and Pietro Colonna.

Torriti’s mosaic, dating from 1295, is divided into two parts. The central medallion in the apse shows the Coronation of the Virgin Mary, while the lower band illustrates the most important moments of her life. In the centre of the medallion, enclosed by concentric circles, Christ and Mary are seated on a large oriental throne. Christ is enthroned like a young emperor and he is placing a jewelled crown on her head; she is dressed in a colourful veil, like a Roman empress. The sun, the moon and a choir of angels are arranged around their feet, while Saint Peter, Saint Paul, and Saint Francis of Assisi along with Pope Nicholas IV flank them on the left. On the right, Torriti portrays Saint John the Baptist, Saint John the Evangelist, Saint Anthony and the donor, Cardinal Colonna.

In the lower apse, mosaic scenes to the left and the right show the life of the Virgin Mary, while the central panel represents the Dormition, telling the story in a way that is typical of Byzantine iconography rather than western narratives. She is lying on a bed, as angels prepare to lift her soul to Heaven, the apostles watch astonished and Christ takes her soul into his arms. Torriti embellishes the scene with two small Franciscan figures and a lay person wearing a 13th century cap.

The Crypt of the Nativity is said to contain wooden relics from the Crib in Bethlehem (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Under the High Altar, the Crypt of the Nativity or Bethlehem Crypt has a crystal reliquary designed by Giuseppe Valadier and said to contain wooden relics from the Crib of the Christ Child in Bethlehem.

The statue in the crypt of Pope Pius IX in prayer is by Ignazio Jacometti, ca 1880, and is over the tomb of Saint Jerome (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The crypt is also the burial place of Saint Jerome, who translated the Bible into Latin or Vulgate version and died in 420. Above his burial place is a kneeling statue of Pope Pius IX, who proclaimed the dogma of the Immaculate Conception on 8 December 1854 and who ordered the reconstruction of the crypt.

In the right transept, the Sistine Chapel or chapel of the Blessed Sacrament, is named after Pope Sixtus V. This chapel, which was designed by Domenico Fontana, includes the tombs of Pope Sixtus V and Pope Pius V. After his ordination as a priest, Saint Ignatius of Loyola celebrated his first Mass in this chapel on 25 December 1538.

Just outside the Sistine Chapel is the tomb of Gian Lorenzo Bernini and his family.

The Assumption of Mary was painted inside the cupola of the Borghese Chapel by Galileo’s friend Ludovico Cardi (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The celebrated icon of the Virgin Mary in the Borghese Chapel is known as Salus Populi Romani, or Health of the Roman People. The icon is said to have saved the people of Rome from the plague. Tradition attributes the icon to Saint Luke the Evangelist, and this richly decorated chapel was designed for Pope Paul V Borghese.

The Assumption of Mary was painted inside the cupola of the chapel by Ludovico Cardi nicknamed Il Cigoli. Above the clouds, the Virgin Mary is seen being transported towards Heaven. The moon beneath her feet is painted as it was seen through the telescope of Galileo, who was a friend of Cigoli.

The floor of the church is paved in opus sectile mosaic, featuring the Borghese heraldic arms of an eagle and a dragon.

The 1995 rose window symbolises the link between the Old Covenant and the New Covenant (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

In 1995, a new, rose window in stained glass was created for the main façade by Giovanni Hajnal. It reaffirms the declaration of the Second Vatican Council that Mary, the exalted daughter of Zion, is the link that unites the Church as the New Covenant to the Old Testament and the Covenant with the Children of Israel. To symbolise the Old Testament, Hajnal used the two tablets of the Ten Commandments and the seven-branched Menorah or candlestick, and for the New Testament he used the Cross, the Host and the Chalice of the Eucharist.

The 14th century campanile or bell tower is the highest in Rome at 75 metres. It was erected by Pope Gregory XI after his return from Avignon.

Outside, the column in Piazza Santa Maria Maggiore came from the Basilica of Constantine in the Forum and was designed by Carlo Maderno. It was erected in 1615 and has since become the model for numerous Marian columns throughout the Catholic world.

The church is served by Redemptorist and Dominican priests. In the portico, there is a fine statue by Bernini and Lucenti of King Philip IV of Spain, one of the benefactors of the church. The King of Spain is ex officio a lay canon of the basilica. In a similar manner, the President of France is ex officio an honorary canon of Saint John Lateran.

The development of the city has taken away the impact of Santa Maria Major’s commanding position on the summit of the Esquiline Hill, but the church is still considered by many to be the most beautiful church in Rome after Saint Peter’s.

Inside the Baptistery in Saint Mary Major (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

09 March 2025

Saint Aloysius Church in

Somers Town, a church

that reflects the liturgical

changes of Vatican II

Saint Aloysius Church, near Euston Station, was designed in the 1960s by John Newton of Burles Newton and Partners (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Patrick Comerford

Saint Aloysius Church, the Roman Catholic parish church in Somers Town, stands at the corner of Phoenix Road and Eversholt Street, south of Camden Town in London. Some people seems to walk past without realising the building is a church, yet it is familiar to many commuters and train passengers because it is only a short walk from Euston Station.

Saint Aloysius Church is just a short stroll from Saint Mary’s Church, Somers Town, also on Eversholt Street, and which I was writing about last Sunday (2 March 2025).

Saint Aloysius was built in the mid-1960s to replace one of the earliest churches of the Catholic Revival in London. The church is noteworthy for its modern design with its conspicuous brick drum and it still has many of its original 1960s fittings.

A broad flight of concrete steps leads up to the main entrance of Saint Aloysius Church (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

As the district of Somers Town was being developed in the late 18th century, it became a centre for French émigré clergy in London in the aftermath of the French Revolution, and Abbé Chantrel established a chapel there in 1798.

The early chapel was replaced in 1808 by a new and larger building in the classical style built for Abbé Carron on Phoenix Road.

The area needed a larger church by the 1960s. The site next to the old church was given by the French religious order, the Faithful Companions of Jesus, and a new convent was built for them on the site of the old church and presbytery.

The coat-of-arms of the Gonzaga family on the frosted glass of the church doors (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

The church is named after the Jesuit saint and aristocrat, Saint Aloysius Gonzaga (1568-1591) from Milan. Aloysius is the Latin form of his Italian given name, Luigi. He was still a student preparing for ordination in Rome when he died while caring for the victims of a serious epidemic. He was beatified in 1605 and canonised a saint in 1726.

James Joyce, who was educated by the Jesuits at Clongowes Wood College, Co Kildare, and Belvedere College, Dublin, chose Aloysius Gonzaga as his confirmation name in 1891.

The site of Saint Aloysius Church is largely enclosed on three sides, with its principal frontage on Phoenix Road and a smaller frontage on Eversholt Street. The natural level of the site was 6 ft below pavement level and the architect took advantage of this to provide a parish hall and some car parking space underneath the church.

The church, with a hall and youth centre beneath and a presbytery attached to it, was designed by John Newton of Burles Newton and Partners of London, Southend and Manchester. This was one of the most active architectural practices working for the Catholic Church at that time, and they designed many Catholic churches in London and the south-east at the time.

Many visitors say Saint Aloysius Church feels welcoming because its shape seems to embrace the congregation (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

The church was built in 1966-1967 according to the liturgical advances introduced with the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s, including the celebration of the Mass facing the people. The foundation stone was laid by Cardinal Heenan on 15 October 1967. The contractors were Marshall-Andrew and the consulting engineers were Ove Arup.

A broad flight of concrete steps leads up to the main entrance at the right hand end of the podium, with a sunken area to the remainder allowing light to the windows of the lower hall.

There are four large rectangular windows in the main front elevation of the podium with a small copper drum over the Baptistry beside the entrance. The frosted glass on the main doors includes representations of the Gonzaga family’s coat-of-arms and of Saint Aloysius Gonzaga.

The oval raised roof is designed so that worship is more focused on the centre of the church (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Inside, the church is a beautiful space, with the glazed narthex leading directly into the body of the church. Many visitors say it feels welcoming because its shape seems to embrace the congregation. The subtle lighting and the colourful stained glass and mosaics contrast with the starkness of the concrete. Inside, there is ceramic work by Adam Kossowski and windows by the Whitefriars studio and Goddard and Gibbs, both since closed.

The oval raised roof is designed so that worship is more focused on the centre of the church, with the circular rooflight pushed to the east of the oval over the altar.

The main body of the church is an elliptical brick drum with a continuous concrete clerestory set on a raised flat-roofed brick podium that is bookended by the taller presbytery and narthex. The juxtaposition of straight and curved elements is effective.

The Baptistry windows are by the Whitefriars studio (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

The drum clerestory has abstract stained glass by the Whitefriars studio, the successors of James Powell and Sons, which also provided the Baptistry windows.

The space under the drum includes the sanctuary and the main seating area and it is supported on concrete columns with a continuous ambulatory, off which open the Lady Chapel and Blessed Sacrament Chapel, the Baptistry and the confessionals.

The large windows in the north wall depicting the Glorious Mysteries of the Rosary are by Goddard and Gibbs and were added in the 1990s.

Four of the five large windows in the north wall depicting the Glorious Mysteries of the Rosary … by Goddard and Gibbs and added in the 1990s (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

To the right of the sanctuary is a recess for the reserved sacrament with a ceramic mural by the exiled Polish artist Adam Kossowski (1905-1986). The church has several fibreglass statues by Gordon Bedingfield.

The floor of the church is Genoa Green terrazzo, the walls are faced with grey Tyrolean plaster, and the ceiling of the drum has Parana pine boarding. The wooden benches are original. The small early 19th-century chamber organ probably came from the earlier church.

Saint Aloysius Church is in the Deanery of Camden in the Diocese of Westminster. The Parish Priest is Canon Jeremy Trood. Previous parish priests include the late Bruce Kent of Pax Christi and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), Bishop Victor Guazzelli appointed Bruce Kent as parish priest oin 1977 but allowied him enough space to engage in his work in the peace movement. But he resigned from the parish when he became the general secretary of CND in 1980.

The ceramic mural by the Polish artist Adam Kossowski (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

• The Parish Mass times are: Sunday (Saturday 6 pm), 10:30 am, 6 pm; Holy Days 9:30 am and 7 pm; weekdays Monday-Tuesday, Thursday-Friday, 9: 30am. Adoration and Benediction, Saturday 5 pm to 5:40 pm.

The Day of Pentecost in one of the Goddard and Gibbs windows in the north wall by, added in the 1990s (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Patrick Comerford

Saint Aloysius Church, the Roman Catholic parish church in Somers Town, stands at the corner of Phoenix Road and Eversholt Street, south of Camden Town in London. Some people seems to walk past without realising the building is a church, yet it is familiar to many commuters and train passengers because it is only a short walk from Euston Station.

Saint Aloysius Church is just a short stroll from Saint Mary’s Church, Somers Town, also on Eversholt Street, and which I was writing about last Sunday (2 March 2025).

Saint Aloysius was built in the mid-1960s to replace one of the earliest churches of the Catholic Revival in London. The church is noteworthy for its modern design with its conspicuous brick drum and it still has many of its original 1960s fittings.

A broad flight of concrete steps leads up to the main entrance of Saint Aloysius Church (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

As the district of Somers Town was being developed in the late 18th century, it became a centre for French émigré clergy in London in the aftermath of the French Revolution, and Abbé Chantrel established a chapel there in 1798.

The early chapel was replaced in 1808 by a new and larger building in the classical style built for Abbé Carron on Phoenix Road.

The area needed a larger church by the 1960s. The site next to the old church was given by the French religious order, the Faithful Companions of Jesus, and a new convent was built for them on the site of the old church and presbytery.

The coat-of-arms of the Gonzaga family on the frosted glass of the church doors (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

The church is named after the Jesuit saint and aristocrat, Saint Aloysius Gonzaga (1568-1591) from Milan. Aloysius is the Latin form of his Italian given name, Luigi. He was still a student preparing for ordination in Rome when he died while caring for the victims of a serious epidemic. He was beatified in 1605 and canonised a saint in 1726.

James Joyce, who was educated by the Jesuits at Clongowes Wood College, Co Kildare, and Belvedere College, Dublin, chose Aloysius Gonzaga as his confirmation name in 1891.

The site of Saint Aloysius Church is largely enclosed on three sides, with its principal frontage on Phoenix Road and a smaller frontage on Eversholt Street. The natural level of the site was 6 ft below pavement level and the architect took advantage of this to provide a parish hall and some car parking space underneath the church.

The church, with a hall and youth centre beneath and a presbytery attached to it, was designed by John Newton of Burles Newton and Partners of London, Southend and Manchester. This was one of the most active architectural practices working for the Catholic Church at that time, and they designed many Catholic churches in London and the south-east at the time.

Many visitors say Saint Aloysius Church feels welcoming because its shape seems to embrace the congregation (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

The church was built in 1966-1967 according to the liturgical advances introduced with the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s, including the celebration of the Mass facing the people. The foundation stone was laid by Cardinal Heenan on 15 October 1967. The contractors were Marshall-Andrew and the consulting engineers were Ove Arup.

A broad flight of concrete steps leads up to the main entrance at the right hand end of the podium, with a sunken area to the remainder allowing light to the windows of the lower hall.

There are four large rectangular windows in the main front elevation of the podium with a small copper drum over the Baptistry beside the entrance. The frosted glass on the main doors includes representations of the Gonzaga family’s coat-of-arms and of Saint Aloysius Gonzaga.

The oval raised roof is designed so that worship is more focused on the centre of the church (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

Inside, the church is a beautiful space, with the glazed narthex leading directly into the body of the church. Many visitors say it feels welcoming because its shape seems to embrace the congregation. The subtle lighting and the colourful stained glass and mosaics contrast with the starkness of the concrete. Inside, there is ceramic work by Adam Kossowski and windows by the Whitefriars studio and Goddard and Gibbs, both since closed.

The oval raised roof is designed so that worship is more focused on the centre of the church, with the circular rooflight pushed to the east of the oval over the altar.

The main body of the church is an elliptical brick drum with a continuous concrete clerestory set on a raised flat-roofed brick podium that is bookended by the taller presbytery and narthex. The juxtaposition of straight and curved elements is effective.

The Baptistry windows are by the Whitefriars studio (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

The drum clerestory has abstract stained glass by the Whitefriars studio, the successors of James Powell and Sons, which also provided the Baptistry windows.

The space under the drum includes the sanctuary and the main seating area and it is supported on concrete columns with a continuous ambulatory, off which open the Lady Chapel and Blessed Sacrament Chapel, the Baptistry and the confessionals.

The large windows in the north wall depicting the Glorious Mysteries of the Rosary are by Goddard and Gibbs and were added in the 1990s.

Four of the five large windows in the north wall depicting the Glorious Mysteries of the Rosary … by Goddard and Gibbs and added in the 1990s (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

To the right of the sanctuary is a recess for the reserved sacrament with a ceramic mural by the exiled Polish artist Adam Kossowski (1905-1986). The church has several fibreglass statues by Gordon Bedingfield.

The floor of the church is Genoa Green terrazzo, the walls are faced with grey Tyrolean plaster, and the ceiling of the drum has Parana pine boarding. The wooden benches are original. The small early 19th-century chamber organ probably came from the earlier church.

Saint Aloysius Church is in the Deanery of Camden in the Diocese of Westminster. The Parish Priest is Canon Jeremy Trood. Previous parish priests include the late Bruce Kent of Pax Christi and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), Bishop Victor Guazzelli appointed Bruce Kent as parish priest oin 1977 but allowied him enough space to engage in his work in the peace movement. But he resigned from the parish when he became the general secretary of CND in 1980.

The ceramic mural by the Polish artist Adam Kossowski (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

• The Parish Mass times are: Sunday (Saturday 6 pm), 10:30 am, 6 pm; Holy Days 9:30 am and 7 pm; weekdays Monday-Tuesday, Thursday-Friday, 9: 30am. Adoration and Benediction, Saturday 5 pm to 5:40 pm.

The Day of Pentecost in one of the Goddard and Gibbs windows in the north wall by, added in the 1990s (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2025)

03 December 2024

Daily prayer in Advent 2024:

3, Tuesday 3 December 2024

‘Blessed are the eyes that see what you see!’ (Luke 10: 23) … street art in Plaza de Judería in Malaga (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

The Season of Advent – and the real countdown to Christmas – began on Sunday with the First Sunday of Advent (1 December 2024). The Calendar of the Church of England in Common Worship today (3 December) remembers Saint Francis Xavier (1552), Missionary, Apostle of the Indies.

Before the day begins, I am taking some quiet time this morning to give thanks, to reflect, to pray and to read in these ways:

1, today’s Gospel reading;

2, a short reflection;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary;

4, the Collects and Post-Communion prayer of the day.

‘Blessed are the eyes that see what you see!’ (Luke 10: 23) … what do we see in our own eyes?

Luke 10: 21-24 (NRSVA):

21 At that same hour Jesus rejoiced in the Holy Spirit and said, ‘I thank you, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, because you have hidden these things from the wise and the intelligent and have revealed them to infants; yes, Father, for such was your gracious will. 22 All things have been handed over to me by my Father; and no one knows who the Son is except the Father, or who the Father is except the Son and anyone to whom the Son chooses to reveal him.’

23 Then turning to the disciples, Jesus said to them privately, ‘Blessed are the eyes that see what you see! 24 For I tell you that many prophets and kings desired to see what you see, but did not see it, and to hear what you hear, but did not hear it.’

‘Blessed are the eyes that see what you see!’ (Luke 10: 23) … street art in Brick Lane in the East End, London (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Today’s reflection: