Patrick Comerford

These eight days mark the Jewish holiday of Passover, which is celebrated in the early spring, from the 15th until the 22nd day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Passover began this year on Wednesday evening, 5 April 2023 and continues until 13 April 2023.

Passover or Pesach is the most celebrated of all the Jewish holidays. regardless of religious observance. It commemorates the emancipation of the Israelites from slavery in ancient Egypt. Pesach is marked by avoiding leaven, and the highlight of the holiday is the Seder meals that include four cups of wine, eating matzah and bitter herbs, and retelling the story of the Exodus.

During many decades of slavery in Egypt, the pharaohs subjected the Israelites to back-breaking labour and unbearable horrors. God saw their distress and sent Moses to Pharaoh with the message: ‘Let my people go, so that they may worship me’ (Exodus 8: 1; 9: 1).

Despite numerous warnings, Pharaoh refused to heed God’s command. But his resistance was broken by ten plagues, culminating in the death of the first-born. Pharaoh virtually chased his former slaves out of the land. The Israelites left in such a hurry that the bread they baked as provisions for the exodus did not have time to rise.

On that night, 600,000 adult males, and many more women and children, left Egypt and began the trek to Mount Sinai, to religious freedom and to freedom as a people.

Nine days ago, on 29 March, the Jewish American journalist Evan Gershkovich of the Wall Street Journal was arrested by Russia’s security services on false charges and he faces a sentence of up to 20 years in prison.

Evan (31), is the American-son of Soviet-born Jewish exiles who settled in New Jersey,and the grandson of a Ukrainian Jewish Holocaust survivor. He is spending this Passover locked up in Moscow’s notorious Lefortovo prison, denied all contact with the outside world.

When Evan’s mother Ella was 22, she fled the Soviet Union using Israeli documents. She was whisked across the Iron Curtain by her own mother, a Ukrainian nurse and Holocaust survivor who would weep when she talked about the survivors of extermination camps she treated at a Polish military hospital at the end of World War II. Before fleeing Russia, they heard rumours that Soviet Jews were about to be deported to Siberia.

Evan’s father, Mikhail, also left the Soviet Union as part of the same wave of Jewish migration. The couple met in Detroit then moved to New Jersey where Evan and his elder sister Dusya grew up.

The Wall Street Journal asked Jews around the world to raise awareness of Evan’s plight this week by setting a place for Evan at their Seder table and sharing a picture along with the hashtags #FreeEvan and #IStandWithEvan.

Rabbi Angela Buchdahl, the senior rabbi at Central Synagogue in New York, announced on her Facebook page this week that she was leaving an empty chair at her Seder for Evan, and she urged others to do the same.

She wrote: ‘At our festival of freedom, may we remember those for whom the promise of freedom remains unfulfilled. Let us raise up God’s demand for justice as our own: “Let my people go”.’

To learn more about Evan, read this article from the Wall Street Journal: ‘Evan Gershkovich Loved Russia, the Country That Turned on Him.’

חַג פֵּסַח שַׂמֵחַ Chag Pesach Sameach

Shabbat Shalom

07 April 2023

Praying at the Stations of the Cross in

Lent 2023: 7 April 2023 (Station 13)

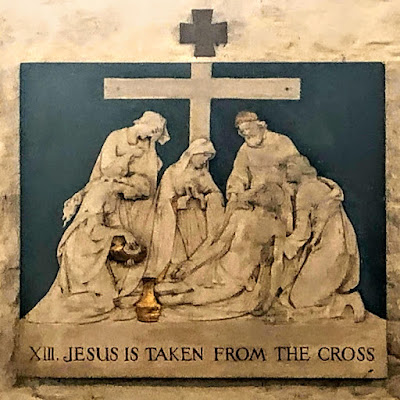

‘Jesus is Taken from the Cross’ … Station XIII in the Stations of the Cross in Saint Dunstan and All Saints’ Church, Stepney (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

Patrick Comerford

We are coming close to the end of Holy Week, the last and closing week of Lent. The services in the Wolverton parishes today (15 April 2022) include ‘Prayers for the Journey’ followed by the Churches Together in Wolverton Walk of Witness, beginning at Holy Trinity Church (10 am), a short service outside the Bath House in Wolverton (11 am) and ‘The Last Hour’ in Holy Trinity (2 pm). The Lord’s Passion is being marked in Saint Mary and Saint Giles Church, Stony Stratford, at 3 pm.

Before today begins, I am taking some time early this morning for prayer, reflection and reading. In these two weeks of Passiontide this year, Passion Week and Holy Week, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, Short reflections on the Stations of the Cross, illustrated by images in Saint Dunstan’s and All Saints’ Church, the Church of England parish church in Stepney, in the East End of London, and the Roman Catholic Church of Saint Francis de Sales in Wolverton;

2, the Gospel reading of the day in the lectionary adapted in the Church of England;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

Station 13, Jesus is taken down from the Cross:

The Thirteenth Station in the Stations of the Cross has a traditional description such as ‘Jesus is taken down from the Cross.’

In the Synoptic Gospels, Saint Matthew, Saint Mark and Saint Luke say Joseph of Arimathea, a member of the council, asked Pilate for the body of Jesus, took his body, and wrapped him in a clean linen cloth (Matthew 27: 28; Mark 15: 43, 46; Luke 23: 50-53); Saint John’s Gospel adds that Nicodemus helped Joseph with the preparation of the body for burial.

The Gospel writers say many women were present as Christ died on the Cross (Matthew 27: 55; Luke 23: 55), and they name his mother Mary (John 19: 25-27), her sister Mary, the wife of Clopas (John 19: 25), Mary Magdalene (Matthew 27: 56; Mark 15: 40, 47; John 19: 25), Mary the mother of James and Joseph (Matthew 27: 56; Mark 15: 40, 47), Mary the mother of the sons of Zebedee (Matthew 27: 56), and Salome (Mark 15: 40).

The only man at the Cross on Good Friday, apart from those who condemned Christ and the two thieves, is Saint John the Beloved Disciple (John 19: 26).

None of the Gospels, however, says that the Virgin Mary held the body of her son when he was taken down from the Cross and before he was buried. Yet this has become a popular image in Passion scenes, from Michelangelo’s Pieta to the statues that dominate Good Friday processions in Italy, Spain and Portugal.

In Station XIII in Stepney, a group of five gather around the body of Christ after he has been taken down from the Cross, his head falling over, his arms and legs limp and lifeless: the Virgin Mary, two other Marys, Saint John and Joseph of Arimathea.

Joseph of Arimathea waits to take custody of the body, while Saint Mary Magdalene with blond tresses and ringlets, prepares the myrrh that she will bring to the tomb on Easter morning.

The words below read: ‘Jesus is Taken from the Cross.’

In Station XIII in Wolverton, three figures gather around the dead body at the foot of the Cross: the Virgin Mary, Saint John and Saint Mary Magdalene, who has fallen to her knees. The cloth draped on the empty arms of the Cross foretells the folded clothes to be seen at the empty tomb early on Sunday morning.

The words below read: ‘Descent from the Cross.’

‘Descent from the Cross’ … Station XIII in the Stations of the Cross in Saint Francis de Sales Church, Wolverton (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

John 18: 1 to 19: 42 (NRSVA):

1 After Jesus had spoken these words, he went out with his disciples across the Kidron valley to a place where there was a garden, which he and his disciples entered. 2 Now Judas, who betrayed him, also knew the place, because Jesus often met there with his disciples. 3 So Judas brought a detachment of soldiers together with police from the chief priests and the Pharisees, and they came there with lanterns and torches and weapons. 4 Then Jesus, knowing all that was to happen to him, came forward and asked them, ‘For whom are you looking?’ 5 They answered, ‘Jesus of Nazareth.’ Jesus replied, ‘I am he.’ Judas, who betrayed him, was standing with them. 6 When Jesus said to them, ‘I am he’, they stepped back and fell to the ground. 7 Again he asked them, ‘For whom are you looking?’ And they said, ‘Jesus of Nazareth.’ 8 Jesus answered, ‘I told you that I am he. So if you are looking for me, let these men go.’ 9 This was to fulfil the word that he had spoken, ‘I did not lose a single one of those whom you gave me.’ 10 Then Simon Peter, who had a sword, drew it, struck the high priest’s slave, and cut off his right ear. The slave’s name was Malchus. 11 Jesus said to Peter, ‘Put your sword back into its sheath. Am I not to drink the cup that the Father has given me?’

12 So the soldiers, their officer, and the Jewish police arrested Jesus and bound him. 13 First they took him to Annas, who was the father-in-law of Caiaphas, the high priest that year. 14 Caiaphas was the one who had advised the Jews that it was better to have one person die for the people.

15 Simon Peter and another disciple followed Jesus. Since that disciple was known to the high priest, he went with Jesus into the courtyard of the high priest, 16 but Peter was standing outside at the gate. So the other disciple, who was known to the high priest, went out, spoke to the woman who guarded the gate, and brought Peter in. 17 The woman said to Peter, ‘You are not also one of this man’s disciples, are you?’ He said, ‘I am not.’ 18 Now the slaves and the police had made a charcoal fire because it was cold, and they were standing round it and warming themselves. Peter also was standing with them and warming himself.

19 Then the high priest questioned Jesus about his disciples and about his teaching. 20 Jesus answered, ‘I have spoken openly to the world; I have always taught in synagogues and in the temple, where all the Jews come together. I have said nothing in secret. 21 Why do you ask me? Ask those who heard what I said to them; they know what I said.’ 22 When he had said this, one of the police standing nearby struck Jesus on the face, saying, ‘Is that how you answer the high priest?’ 23 Jesus answered, ‘If I have spoken wrongly, testify to the wrong. But if I have spoken rightly, why do you strike me?’ 24 Then Annas sent him bound to Caiaphas the high priest.

25 Now Simon Peter was standing and warming himself. They asked him, ‘You are not also one of his disciples, are you?’ He denied it and said, ‘I am not.’ 26 One of the slaves of the high priest, a relative of the man whose ear Peter had cut off, asked, ‘Did I not see you in the garden with him?’ 27 Again Peter denied it, and at that moment the cock crowed.

28 Then they took Jesus from Caiaphas to Pilate’s headquarters. It was early in the morning. They themselves did not enter the headquarters, so as to avoid ritual defilement and to be able to eat the Passover. 29 So Pilate went out to them and said, ‘What accusation do you bring against this man?’ 30 They answered, ‘If this man were not a criminal, we would not have handed him over to you.’ 31 Pilate said to them, ‘Take him yourselves and judge him according to your law.’ The Jews replied, ‘We are not permitted to put anyone to death.’ 32 (This was to fulfil what Jesus had said when he indicated the kind of death he was to die.)

33 Then Pilate entered the headquarters again, summoned Jesus, and asked him, ‘Are you the King of the Jews?’ 34 Jesus answered, ‘Do you ask this on your own, or did others tell you about me?’ 35 Pilate replied, ‘I am not a Jew, am I? Your own nation and the chief priests have handed you over to me. What have you done?’ 36 Jesus answered, ‘My kingdom is not from this world. If my kingdom were from this world, my followers would be fighting to keep me from being handed over to the Jews. But as it is, my kingdom is not from here.’ 37 Pilate asked him, ‘So you are a king?’ Jesus answered, ‘You say that I am a king. For this I was born, and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice.’ 38 Pilate asked him, ‘What is truth?’

After he had said this, he went out to the Jews again and told them, ‘I find no case against him. 39 But you have a custom that I release someone for you at the Passover. Do you want me to release for you the King of the Jews?’ 40 They shouted in reply, ‘Not this man, but Barabbas!’ Now Barabbas was a bandit.

1 Then Pilate took Jesus and had him flogged. 2 And the soldiers wove a crown of thorns and put it on his head, and they dressed him in a purple robe. 3 They kept coming up to him, saying, ‘Hail, King of the Jews!’ and striking him on the face. 4 Pilate went out again and said to them, ‘Look, I am bringing him out to you to let you know that I find no case against him.’ 5 So Jesus came out, wearing the crown of thorns and the purple robe. Pilate said to them, ‘Here is the man!’ 6 When the chief priests and the police saw him, they shouted, ‘Crucify him! Crucify him!’ Pilate said to them, ‘Take him yourselves and crucify him; I find no case against him.’ 7 The Jews answered him, ‘We have a law, and according to that law he ought to die because he has claimed to be the Son of God.’

8 Now when Pilate heard this, he was more afraid than ever. 9 He entered his headquarters again and asked Jesus, ‘Where are you from?’ But Jesus gave him no answer. 10 Pilate therefore said to him, ‘Do you refuse to speak to me? Do you not know that I have power to release you, and power to crucify you?’ 11 Jesus answered him, ‘You would have no power over me unless it had been given you from above; therefore the one who handed me over to you is guilty of a greater sin.’ 12 From then on Pilate tried to release him, but the Jews cried out, ‘If you release this man, you are no friend of the emperor. Everyone who claims to be a king sets himself against the emperor.’

13 When Pilate heard these words, he brought Jesus outside and sat on the judge’s bench at a place called The Stone Pavement, or in Hebrew Gabbatha. 14 Now it was the day of Preparation for the Passover; and it was about noon. He said to the Jews, ‘Here is your King!’ 15 They cried out, ‘Away with him! Away with him! Crucify him!’ Pilate asked them, ‘Shall I crucify your King?’ The chief priests answered, ‘We have no king but the emperor.’ 16 Then he handed him over to them to be crucified.

So they took Jesus; 17 and carrying the cross by himself, he went out to what is called The Place of the Skull, which in Hebrew is called Golgotha. 18 There they crucified him, and with him two others, one on either side, with Jesus between them. 19 Pilate also had an inscription written and put on the cross. It read, ‘Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews.’ 20 Many of the Jews read this inscription, because the place where Jesus was crucified was near the city; and it was written in Hebrew, in Latin, and in Greek. 21 Then the chief priests of the Jews said to Pilate, ‘Do not write, “The King of the Jews”, but, “This man said, I am King of the Jews”.’ 22 Pilate answered, ‘What I have written I have written.’ 23 When the soldiers had crucified Jesus, they took his clothes and divided them into four parts, one for each soldier. They also took his tunic; now the tunic was seamless, woven in one piece from the top. 24 So they said to one another, ‘Let us not tear it, but cast lots for it to see who will get it.’ This was to fulfil what the scripture says,

‘They divided my clothes among themselves,

and for my clothing they cast lots.’

25 And that is what the soldiers did.

Meanwhile, standing near the cross of Jesus were his mother, and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene. 26 When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple whom he loved standing beside her, he said to his mother, ‘Woman, here is your son.’ 27 Then he said to the disciple, ‘Here is your mother.’ And from that hour the disciple took her into his own home.

28 After this, when Jesus knew that all was now finished, he said (in order to fulfil the scripture), ‘I am thirsty.’ 29 A jar full of sour wine was standing there. So they put a sponge full of the wine on a branch of hyssop and held it to his mouth. 30 When Jesus had received the wine, he said, ‘It is finished.’ Then he bowed his head and gave up his spirit.

31 Since it was the day of Preparation, the Jews did not want the bodies left on the cross during the sabbath, especially because that sabbath was a day of great solemnity. So they asked Pilate to have the legs of the crucified men broken and the bodies removed. 32 Then the soldiers came and broke the legs of the first and of the other who had been crucified with him. 33 But when they came to Jesus and saw that he was already dead, they did not break his legs. 34 Instead, one of the soldiers pierced his side with a spear, and at once blood and water came out. 35 (He who saw this has testified so that you also may believe. His testimony is true, and he knows that he tells the truth.) 36 These things occurred so that the scripture might be fulfilled, ‘None of his bones shall be broken.’ 37 And again another passage of scripture says, ‘They will look on the one whom they have pierced.’

38 After these things, Joseph of Arimathea, who was a disciple of Jesus, though a secret one because of his fear of the Jews, asked Pilate to let him take away the body of Jesus. Pilate gave him permission; so he came and removed his body. 39 Nicodemus, who had at first come to Jesus by night, also came, bringing a mixture of myrrh and aloes, weighing about a hundred pounds. 40 They took the body of Jesus and wrapped it with the spices in linen cloths, according to the burial custom of the Jews. 41 Now there was a garden in the place where he was crucified, and in the garden there was a new tomb in which no one had ever been laid. 42 And so, because it was the Jewish day of Preparation, and the tomb was nearby, they laid Jesus there.

Today’s Prayer:

The theme in this week’s prayer diary of the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel) is ‘Good Neighbours in Times of War: a View from Europe.’ This theme was introduced on Sunday by the Ven Dr Leslie Nathaniel, Archdeacon of the East, Germany and Northern Europe, with an adaptation of his contribution to USPG’s Lent Course ‘Who is our neighbour,’ which I have edited for USPG.

The USPG Prayer Diary today (Friday 7 April 2023, Good Friday) invites us to pray:

Let us pray for those who have lost loved ones in the service of others. May we kneel with Mary at the foot of the cross and know love’s endeavour, love’s expense.

The Collect:

Almighty Father,

look with mercy on this your family

for which our Lord Jesus Christ was content to be betrayed

and given up into the hands of sinners

and to suffer death upon the cross;

who is alive and glorified with you and the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

Good Friday 2023 … images from a variety of locations (Photographs: Patrick Comerford)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Patrick Comerford

We are coming close to the end of Holy Week, the last and closing week of Lent. The services in the Wolverton parishes today (15 April 2022) include ‘Prayers for the Journey’ followed by the Churches Together in Wolverton Walk of Witness, beginning at Holy Trinity Church (10 am), a short service outside the Bath House in Wolverton (11 am) and ‘The Last Hour’ in Holy Trinity (2 pm). The Lord’s Passion is being marked in Saint Mary and Saint Giles Church, Stony Stratford, at 3 pm.

Before today begins, I am taking some time early this morning for prayer, reflection and reading. In these two weeks of Passiontide this year, Passion Week and Holy Week, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, Short reflections on the Stations of the Cross, illustrated by images in Saint Dunstan’s and All Saints’ Church, the Church of England parish church in Stepney, in the East End of London, and the Roman Catholic Church of Saint Francis de Sales in Wolverton;

2, the Gospel reading of the day in the lectionary adapted in the Church of England;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

Station 13, Jesus is taken down from the Cross:

The Thirteenth Station in the Stations of the Cross has a traditional description such as ‘Jesus is taken down from the Cross.’

In the Synoptic Gospels, Saint Matthew, Saint Mark and Saint Luke say Joseph of Arimathea, a member of the council, asked Pilate for the body of Jesus, took his body, and wrapped him in a clean linen cloth (Matthew 27: 28; Mark 15: 43, 46; Luke 23: 50-53); Saint John’s Gospel adds that Nicodemus helped Joseph with the preparation of the body for burial.

The Gospel writers say many women were present as Christ died on the Cross (Matthew 27: 55; Luke 23: 55), and they name his mother Mary (John 19: 25-27), her sister Mary, the wife of Clopas (John 19: 25), Mary Magdalene (Matthew 27: 56; Mark 15: 40, 47; John 19: 25), Mary the mother of James and Joseph (Matthew 27: 56; Mark 15: 40, 47), Mary the mother of the sons of Zebedee (Matthew 27: 56), and Salome (Mark 15: 40).

The only man at the Cross on Good Friday, apart from those who condemned Christ and the two thieves, is Saint John the Beloved Disciple (John 19: 26).

None of the Gospels, however, says that the Virgin Mary held the body of her son when he was taken down from the Cross and before he was buried. Yet this has become a popular image in Passion scenes, from Michelangelo’s Pieta to the statues that dominate Good Friday processions in Italy, Spain and Portugal.

In Station XIII in Stepney, a group of five gather around the body of Christ after he has been taken down from the Cross, his head falling over, his arms and legs limp and lifeless: the Virgin Mary, two other Marys, Saint John and Joseph of Arimathea.

Joseph of Arimathea waits to take custody of the body, while Saint Mary Magdalene with blond tresses and ringlets, prepares the myrrh that she will bring to the tomb on Easter morning.

The words below read: ‘Jesus is Taken from the Cross.’

In Station XIII in Wolverton, three figures gather around the dead body at the foot of the Cross: the Virgin Mary, Saint John and Saint Mary Magdalene, who has fallen to her knees. The cloth draped on the empty arms of the Cross foretells the folded clothes to be seen at the empty tomb early on Sunday morning.

The words below read: ‘Descent from the Cross.’

‘Descent from the Cross’ … Station XIII in the Stations of the Cross in Saint Francis de Sales Church, Wolverton (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

John 18: 1 to 19: 42 (NRSVA):

1 After Jesus had spoken these words, he went out with his disciples across the Kidron valley to a place where there was a garden, which he and his disciples entered. 2 Now Judas, who betrayed him, also knew the place, because Jesus often met there with his disciples. 3 So Judas brought a detachment of soldiers together with police from the chief priests and the Pharisees, and they came there with lanterns and torches and weapons. 4 Then Jesus, knowing all that was to happen to him, came forward and asked them, ‘For whom are you looking?’ 5 They answered, ‘Jesus of Nazareth.’ Jesus replied, ‘I am he.’ Judas, who betrayed him, was standing with them. 6 When Jesus said to them, ‘I am he’, they stepped back and fell to the ground. 7 Again he asked them, ‘For whom are you looking?’ And they said, ‘Jesus of Nazareth.’ 8 Jesus answered, ‘I told you that I am he. So if you are looking for me, let these men go.’ 9 This was to fulfil the word that he had spoken, ‘I did not lose a single one of those whom you gave me.’ 10 Then Simon Peter, who had a sword, drew it, struck the high priest’s slave, and cut off his right ear. The slave’s name was Malchus. 11 Jesus said to Peter, ‘Put your sword back into its sheath. Am I not to drink the cup that the Father has given me?’

12 So the soldiers, their officer, and the Jewish police arrested Jesus and bound him. 13 First they took him to Annas, who was the father-in-law of Caiaphas, the high priest that year. 14 Caiaphas was the one who had advised the Jews that it was better to have one person die for the people.

15 Simon Peter and another disciple followed Jesus. Since that disciple was known to the high priest, he went with Jesus into the courtyard of the high priest, 16 but Peter was standing outside at the gate. So the other disciple, who was known to the high priest, went out, spoke to the woman who guarded the gate, and brought Peter in. 17 The woman said to Peter, ‘You are not also one of this man’s disciples, are you?’ He said, ‘I am not.’ 18 Now the slaves and the police had made a charcoal fire because it was cold, and they were standing round it and warming themselves. Peter also was standing with them and warming himself.

19 Then the high priest questioned Jesus about his disciples and about his teaching. 20 Jesus answered, ‘I have spoken openly to the world; I have always taught in synagogues and in the temple, where all the Jews come together. I have said nothing in secret. 21 Why do you ask me? Ask those who heard what I said to them; they know what I said.’ 22 When he had said this, one of the police standing nearby struck Jesus on the face, saying, ‘Is that how you answer the high priest?’ 23 Jesus answered, ‘If I have spoken wrongly, testify to the wrong. But if I have spoken rightly, why do you strike me?’ 24 Then Annas sent him bound to Caiaphas the high priest.

25 Now Simon Peter was standing and warming himself. They asked him, ‘You are not also one of his disciples, are you?’ He denied it and said, ‘I am not.’ 26 One of the slaves of the high priest, a relative of the man whose ear Peter had cut off, asked, ‘Did I not see you in the garden with him?’ 27 Again Peter denied it, and at that moment the cock crowed.

28 Then they took Jesus from Caiaphas to Pilate’s headquarters. It was early in the morning. They themselves did not enter the headquarters, so as to avoid ritual defilement and to be able to eat the Passover. 29 So Pilate went out to them and said, ‘What accusation do you bring against this man?’ 30 They answered, ‘If this man were not a criminal, we would not have handed him over to you.’ 31 Pilate said to them, ‘Take him yourselves and judge him according to your law.’ The Jews replied, ‘We are not permitted to put anyone to death.’ 32 (This was to fulfil what Jesus had said when he indicated the kind of death he was to die.)

33 Then Pilate entered the headquarters again, summoned Jesus, and asked him, ‘Are you the King of the Jews?’ 34 Jesus answered, ‘Do you ask this on your own, or did others tell you about me?’ 35 Pilate replied, ‘I am not a Jew, am I? Your own nation and the chief priests have handed you over to me. What have you done?’ 36 Jesus answered, ‘My kingdom is not from this world. If my kingdom were from this world, my followers would be fighting to keep me from being handed over to the Jews. But as it is, my kingdom is not from here.’ 37 Pilate asked him, ‘So you are a king?’ Jesus answered, ‘You say that I am a king. For this I was born, and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice.’ 38 Pilate asked him, ‘What is truth?’

After he had said this, he went out to the Jews again and told them, ‘I find no case against him. 39 But you have a custom that I release someone for you at the Passover. Do you want me to release for you the King of the Jews?’ 40 They shouted in reply, ‘Not this man, but Barabbas!’ Now Barabbas was a bandit.

1 Then Pilate took Jesus and had him flogged. 2 And the soldiers wove a crown of thorns and put it on his head, and they dressed him in a purple robe. 3 They kept coming up to him, saying, ‘Hail, King of the Jews!’ and striking him on the face. 4 Pilate went out again and said to them, ‘Look, I am bringing him out to you to let you know that I find no case against him.’ 5 So Jesus came out, wearing the crown of thorns and the purple robe. Pilate said to them, ‘Here is the man!’ 6 When the chief priests and the police saw him, they shouted, ‘Crucify him! Crucify him!’ Pilate said to them, ‘Take him yourselves and crucify him; I find no case against him.’ 7 The Jews answered him, ‘We have a law, and according to that law he ought to die because he has claimed to be the Son of God.’

8 Now when Pilate heard this, he was more afraid than ever. 9 He entered his headquarters again and asked Jesus, ‘Where are you from?’ But Jesus gave him no answer. 10 Pilate therefore said to him, ‘Do you refuse to speak to me? Do you not know that I have power to release you, and power to crucify you?’ 11 Jesus answered him, ‘You would have no power over me unless it had been given you from above; therefore the one who handed me over to you is guilty of a greater sin.’ 12 From then on Pilate tried to release him, but the Jews cried out, ‘If you release this man, you are no friend of the emperor. Everyone who claims to be a king sets himself against the emperor.’

13 When Pilate heard these words, he brought Jesus outside and sat on the judge’s bench at a place called The Stone Pavement, or in Hebrew Gabbatha. 14 Now it was the day of Preparation for the Passover; and it was about noon. He said to the Jews, ‘Here is your King!’ 15 They cried out, ‘Away with him! Away with him! Crucify him!’ Pilate asked them, ‘Shall I crucify your King?’ The chief priests answered, ‘We have no king but the emperor.’ 16 Then he handed him over to them to be crucified.

So they took Jesus; 17 and carrying the cross by himself, he went out to what is called The Place of the Skull, which in Hebrew is called Golgotha. 18 There they crucified him, and with him two others, one on either side, with Jesus between them. 19 Pilate also had an inscription written and put on the cross. It read, ‘Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews.’ 20 Many of the Jews read this inscription, because the place where Jesus was crucified was near the city; and it was written in Hebrew, in Latin, and in Greek. 21 Then the chief priests of the Jews said to Pilate, ‘Do not write, “The King of the Jews”, but, “This man said, I am King of the Jews”.’ 22 Pilate answered, ‘What I have written I have written.’ 23 When the soldiers had crucified Jesus, they took his clothes and divided them into four parts, one for each soldier. They also took his tunic; now the tunic was seamless, woven in one piece from the top. 24 So they said to one another, ‘Let us not tear it, but cast lots for it to see who will get it.’ This was to fulfil what the scripture says,

‘They divided my clothes among themselves,

and for my clothing they cast lots.’

25 And that is what the soldiers did.

Meanwhile, standing near the cross of Jesus were his mother, and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene. 26 When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple whom he loved standing beside her, he said to his mother, ‘Woman, here is your son.’ 27 Then he said to the disciple, ‘Here is your mother.’ And from that hour the disciple took her into his own home.

28 After this, when Jesus knew that all was now finished, he said (in order to fulfil the scripture), ‘I am thirsty.’ 29 A jar full of sour wine was standing there. So they put a sponge full of the wine on a branch of hyssop and held it to his mouth. 30 When Jesus had received the wine, he said, ‘It is finished.’ Then he bowed his head and gave up his spirit.

31 Since it was the day of Preparation, the Jews did not want the bodies left on the cross during the sabbath, especially because that sabbath was a day of great solemnity. So they asked Pilate to have the legs of the crucified men broken and the bodies removed. 32 Then the soldiers came and broke the legs of the first and of the other who had been crucified with him. 33 But when they came to Jesus and saw that he was already dead, they did not break his legs. 34 Instead, one of the soldiers pierced his side with a spear, and at once blood and water came out. 35 (He who saw this has testified so that you also may believe. His testimony is true, and he knows that he tells the truth.) 36 These things occurred so that the scripture might be fulfilled, ‘None of his bones shall be broken.’ 37 And again another passage of scripture says, ‘They will look on the one whom they have pierced.’

38 After these things, Joseph of Arimathea, who was a disciple of Jesus, though a secret one because of his fear of the Jews, asked Pilate to let him take away the body of Jesus. Pilate gave him permission; so he came and removed his body. 39 Nicodemus, who had at first come to Jesus by night, also came, bringing a mixture of myrrh and aloes, weighing about a hundred pounds. 40 They took the body of Jesus and wrapped it with the spices in linen cloths, according to the burial custom of the Jews. 41 Now there was a garden in the place where he was crucified, and in the garden there was a new tomb in which no one had ever been laid. 42 And so, because it was the Jewish day of Preparation, and the tomb was nearby, they laid Jesus there.

Today’s Prayer:

The theme in this week’s prayer diary of the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel) is ‘Good Neighbours in Times of War: a View from Europe.’ This theme was introduced on Sunday by the Ven Dr Leslie Nathaniel, Archdeacon of the East, Germany and Northern Europe, with an adaptation of his contribution to USPG’s Lent Course ‘Who is our neighbour,’ which I have edited for USPG.

The USPG Prayer Diary today (Friday 7 April 2023, Good Friday) invites us to pray:

Let us pray for those who have lost loved ones in the service of others. May we kneel with Mary at the foot of the cross and know love’s endeavour, love’s expense.

The Collect:

Almighty Father,

look with mercy on this your family

for which our Lord Jesus Christ was content to be betrayed

and given up into the hands of sinners

and to suffer death upon the cross;

who is alive and glorified with you and the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

Good Friday 2023 … images from a variety of locations (Photographs: Patrick Comerford)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)