The Boulevard Saint-Michel is the central axis of the Latin Quarter in Paris (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2024)

Patrick Comerford

The Hotel Europe-Saint-Séverin, where we have been staying in Paris this week, is on the corner of rue St Séverin and The Boulevard Saint-Michel. The boulevard is the central axis of the Latin Quarter and marks the boundary between the 5th and 6th arrondissements. It has long been a centre of student life and activism, but tourism is also a major commercial focus of the street, where designer shops have gradually replaced many small bookshops.

The boulevard Saint-Michel is named in literature and song, from James Joyce’s Ulysses, Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage and Ernest Hemmingway’s The Sun Also Rises to Peter Sarstedt’s 1969 hit ‘Where do you go to my lovely?’

You live in a fancy apartment

Off the Boulevard St Michel

Where you keep your Rolling Stones records

And a friend of Sacha Distel, yes, you do

Could that ‘fancy apartment off the Boulevard Saint Michel’ have been on rue St Séverin, I found myself wondering in an idle moment this morning.

The boulevard Saint-Michel and the boulevard Saint-Germain were two important parts of Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s renovation of Paris on the Left Bank between 1853 and 1870.

Initially, the Boulevard Saint-Michel was known as the boulevard de Sébastopol Rive Gauche, but its name was changed in 1867. The name comes from the gate of the same name destroyed in 1679 and the later Saint-Michel market in the same area.

Many streets in the area disappeared when the Boulevard Saint-Michel was created, although rue St Séverin, where we have been staying, managed to survive.

The Boulevard Saint-Michel marks the boundary between the 5th and 6th arrondissements in Paris (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2024)

I laugh at the stories about the French politician Ferdinand Lop, who stood as a satirical candidate in many elections, and who once made an election promise to extend the Boulevard Saint-Michel to the sea. Asked at which end it would be extended, he answered with panache: ‘It will be extended to the sea at both ends.’

Ferdinand Lop (1891-1974) was a Jewish journalist, draughtsman, English language teacher at the Berlitz School, writer, poet and humourist. He was born Ferdinand Samuel Lop in Marseille on 10 October 1891, and was also known as Samuel Ferdinand-Lop.

Ferdinand Lop was one of three children of Joseph Lop, a prosperous ship chandler, and Benjamine Reine Montel (1871-1956) a schoolteacher in Marseille.

During World War I, Ferdinand relocated to the relative safety of Annecy, in the French Alps but continued to make speeches from a boat on the lake. His eccentric character and zany ideas have been attributed by some to a bout of Spanish flu in 1918.

Lop stood repeatedly as a satirical candidate for the French Presidency and for the Académie française. His humorous and satirical speeches won him a loyal cult following among university students in Paris. During the French Fourth Republic (1946-1958), he stood for election on his offbeat platform, Le Front Lopulaire, with promises that included:

• eliminating poverty after 10 pm;

• building a bridge 300 metres wide, to shelter vagrants;

• extending the roadstead of Brest to Montmartre;

• extending the Boulevard Saint-Michel to the sea – in both directions;

• installing a slide in the Place de la Sorbonne for students;

• nationalising brothels to give prostitutes the benefits of public servant status;

• reducing pregnancy from nine to seven months;

• installing moving pavements to make life easier for wanderers;

• providing a pension to the widow of the unknown soldier;

• relocating Paris to the countryside, for fresh air;

• removing the last coach from Paris métro trains.

Ferdinand Lop wrote numerous booklets, often with evocative titles, including Thoughts and aphorisms (1951), Pétain and history: What I would have said in my inaugural speech at the Académie française if I had been elected (1957), History of the Latin Quarter (1960-1963), Where is France going? (1961) and Antimaxims (1973).

Ferdinand Lop married Sonia Seligman, the daughter of a rabbi, on 18 January 1923 in Paris. He died on 29 October 1974 in Saint-Sébastien-de-Morsent, where he is buried.

One brother, George Lop, was a musician and director of the opera in Montpelier in the 1930s. He was an active Communist politically, and under the Vichy regime he was sent to an internment camp in the Pyrenees. His other brother, Alfred Lop (1898-1971), was a painter and art teacher in Paris. But he was ashamed to be identified with his brother Ferdinand and sold most of his paintings as Alfred Lop-Montel.

Ferdinand Lop promised to extend the Boulevard Saint-Michel ‘to the sea, at both ends’

08 February 2024

Daily prayer in Ordinary

Time with French

saints and writers

6: 8 February 2024

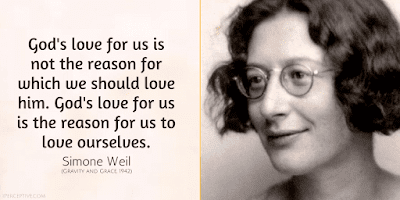

Simone Weil (1909-1943) (Artwork credit: Philosophize This!)

Patrick Comerford

We are in Ordinary Time, the time between Candlemas and the 40 days of Lent, which begins next week on Ash Wednesday.

Charlotte and I are spending two days in Paris. So, in these 11 days in Ordinary Time, my reflections each morning are drawing on the lives of 11 French saints and spiritual writers.

As this series of reflections began, I admitted I am often uncomfortable with many aspects of French spirituality, and that I need to broaden my reading in French spirituality. So, I have turned to 11 figures or writers you might not otherwise expect. They include men and women, Jews and Christians, immigrants and emigrants, monks and philosophers, Catholics and Protestants, and even a few Anglicans.

Before our visit to Paris ends later today, I am taking some quiet time early this morning for reflection, prayer and reading in these ways:

1, A reflection on a French saint or writer in spirituality;

2, today’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

Simone de Beauvoir once said she envied Simone Weil for ‘having a heart that could beat right across the world’

French saints and writers: 6, Simon Weil (1909-1943):

Simone Adolphine Weil (1909-1943) was a philosopher, mystic, teacher, trade unionist and political activist. During her life, Weil became increasingly religious and inclined towards mysticism, although most of her writings did not attract much attention until after her death. By the end of the 20th century, she was widely regarded as an influential writer on religious and spiritual matters.

Simone Weil was born in Paris on 3 February 1909. Her father, Bernard Weil (1872-1955), was a medical doctor from an agnostic Jewish family who moved from Alsace to Paris after the German annexation of Alsace-Lorraine. Her mother, Salomea (Selma) Reinherz (1879-1965), was born into a Jewish family in Rostov-on-Don and grew up in Belgium.

As a teenager, she attended the Lycée Henri IV in the Latin Quarter, close to where we are staying this week. In her late teens, she became involved in the workers’ movement. She wrote political tracts, marched in demonstrations and advocated workers’ rights, and identified as a Marxist, pacifist and trade unionist.

She studied philosophy at the École Normale Supérieure, also in the Latin Quarter and where her contemporaries included Simone de Beauvoir. Later, while teaching philosophy at a girls’ school in Le Puy, she became involved in local political activity. But she never formally joined the French Communist Party and in her 20s she became increasingly critical of Marxism.

She visited Germany in 1932 to help activists, but considered them no match for the Nazis. When Hitler took power in 1933, she helped activists fleeing Germany.

She took part in the French general strike of 1933. Later that year, she arranged for Leon Trotsky to stay at her parents’ apartment in Paris and argued against him both in print and in person, suggesting that élite communist bureaucrats could be just as oppressive as the worst capitalists. She spent more than a year working as a labourer, mostly in car factories, so that she could better understand the working class.

Although she was born into a secular household and raised in agnosticism, from 1935 Simon Weil was attracted to Christianity. The first of three pivotal religious experiences was being moved by the beauty of villagers singing hymns in a procession she saw during a holiday in Portugal.

Despite her professed pacifism, she travelled to the Spanish Civil War in 1936 to join the Republicans, and joined the anarchist Durruti Column. But she was clumsy and near-sighted and after a few weeks burnt herself over a cooking fire. Her parents followed her to Spain, and helped her leave to recuperate in Assisi. A month later, her unit was almost wiped out at Perdiguera in October 1936, and every woman in the group was killed.

While she was in Assisi in the spring of 1937, she experienced a religious ecstasy in the Basilica of Santa Maria degli Angeli, the church where Saint Francis of Assisi had prayed. There she felt compelled to kneel and she prayed for the first time in her life.

She was attracted to Catholicism, spent Holy Week and Easter in 1938 in the Benedictine abbey in Solesmes. There she had a third, more powerful revelation while reciting George Herbert’s poem Love III, after which ‘Christ himself came down and took possession of me.’

She was completely unprepared for this encounter with Christ. Having never read the mystics, she had never conceived of the possibility of a ‘real contact, person to person, here below, between a human being and God. This experience led her to rethink many of her intellectual positions, and also raised the question of baptism.

From then on, her writings became more mystical and spiritual, but retained their focus on social and political issues. But she decided not to be baptised at the time, preferring to remain outside due to ‘the love of those things that are outside Christianity.’

During World War II, she lived for a time in Marseille, receiving spiritual direction from Joseph-Marie Perrin, a Dominican Friar. At that time, she also met the French Catholic writer Gustave Thibon, who later edited some of her work. She was also interested in other religious traditions, including the Greek and Egyptian mysteries, the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita in Hinduism, and Mahayana Buddhism.

Although she was reluctant to leave France, Simone Weil travelled to the US with her family in 1942 for the sake of her parents’ safety; As Jews, they were in danger under the Vichy regime. She lived in an apartment Riverside Drive from July to November, and then returned to Europe to join the French Resistance in London. She was assigned to desk work in London, but this gave her time to write one of her best-known works, The Need for Roots.

She may have been recruited by the Special Operations Executive, with plans to send her back to France as a clandestine wireless operator. Preparations were underway in May 1943 to send her to Thame Park in Oxfordshire for training. But the plan was cancelled soon after, as her failing health became known.

Towards the end of her life, she was working on a tragedy, Venice Saved. The play explores the realisation of her own thoughts on tragedy. The play depicts the plot by a group of Spanish mercenaries to sack Venice in 1618 and how it fails when one conspirator, Jaffier, betrays them to the Venetian authorities, because he feels compassion for the city’s beauty.

The central character is a figure of affliction, a central theme in her religious metaphysics. The play offers a unique insight into her broader philosophical interest in truth and justice.

She was diagnosed with tuberculosis, started to eat less, and even refused food on many occasions. She was probably baptised during this period. As her health quickly deteriorated, she was moved to a sanatorium at Grosvenor Hall in Ashford, Kent, and she died on 24 August 1943 from cardiac failure at the age of 34. The coroner’s report said she had killed herself ‘by refusing to eat whilst the balance of her mind was disturbed.’ Others more kindly say ‘she died of an excess of love.’

Simone Weil's best-known works were published posthumously. It has been said she ‘was maybe the greatest example of living one’s philosophy that has ever existed.’

Maurice Schumann said that since her death there was ‘hardly a day when the thought of her life did not positively influence his own and serve as a moral guide.’ Albert Camus described her as ‘the only great spirit of our times.’ Simone de Beauvoir once said she envied her for ‘having a heart that could beat right across the world.’

In the aftermath of 9/11, Archbishop Rowan Williams, noted the importance of Simon Weil’s concept of ‘the void,’ calling it a ‘breathing space,’ a moment, created by catastrophe, when we are open to God and others. Like her, Archbishop Williams believes that all too often we waste these moments by filling them up with our attempts to make God fit our agendas, in religious language that is ‘formal or self-serving.’

In Waiting for God, Simone Weil says the three forms of implicit love of God are: love of neighbour; love of the beauty of the world; and love of religious ceremonies. Love of neighbour occurs when the strong treat the weak as equals, when people give personal attention to those that otherwise seem invisible, anonymous, or non-existent, and when people look at and listen to the afflicted as they are, without explicitly thinking about God.

Simone Weil recalled that after reading George Herbert’s poem Love III ‘Christ himself came down and took possession of me’

Mark 7: 24-30 (NRSVA):

24 From there he set out and went away to the region of Tyre. He entered a house and did not want anyone to know he was there. Yet he could not escape notice, 25 but a woman whose little daughter had an unclean spirit immediately heard about him, and she came and bowed down at his feet. 26 Now the woman was a Gentile, of Syrophoenician origin. She begged him to cast the demon out of her daughter. 27 He said to her, ‘Let the children be fed first, for it is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs.’ 28 But she answered him, ‘Sir, even the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs.’ 29 Then he said to her, ‘For saying that, you may go – the demon has left your daughter.’ 30 So she went home, found the child lying on the bed, and the demon gone.

Albert Camus described Simone Weil as ‘the only great spirit of our times’

Today’s Prayers (Thursday 8 February 2024):

The theme this week in ‘Pray With the World Church,’ the Prayer Diary of the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel), is ‘Gender Justice in Christ.’ This theme was introduced on Sunday by Ellen McMibanga, Zambia Anglican Council Outreach Programme.

The USPG Prayer Diary today (8 February 2024) invites us to pray in these words:

Thank you, Lord, that we have been made equally by you. May we be unwavering in our support for establishing and upholding justice in our homes, churches and communities.

The Collect:

Almighty God,

you have created the heavens and the earth

and made us in your own image:

teach us to discern your hand in all your works

and your likeness in all your children;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who with you and the Holy Spirit reigns supreme over all things,

now and for ever.

The Post-Communion Prayer:

God our creator,

by your gift

the tree of life was set at the heart of the earthly paradise,

and the bread of life at the heart of your Church:

may we who have been nourished at your table on earth

be transformed by the glory of the Saviour’s cross

and enjoy the delights of eternity;

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

Additional Collect:

Almighty God,

give us reverence for all creation

and respect for every person,

that we may mirror your likeness

in Jesus Christ our Lord.

Yesterday’s Reflection (Canon Frederic Anstruther Cardew, 1866-1942)

Continued Tomorrow (André and Magda Trocmé)

In her dying weeks, Simone Weil was working on ‘Venice Saved’, a play exploring her interests in truth and justice

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Patrick Comerford

We are in Ordinary Time, the time between Candlemas and the 40 days of Lent, which begins next week on Ash Wednesday.

Charlotte and I are spending two days in Paris. So, in these 11 days in Ordinary Time, my reflections each morning are drawing on the lives of 11 French saints and spiritual writers.

As this series of reflections began, I admitted I am often uncomfortable with many aspects of French spirituality, and that I need to broaden my reading in French spirituality. So, I have turned to 11 figures or writers you might not otherwise expect. They include men and women, Jews and Christians, immigrants and emigrants, monks and philosophers, Catholics and Protestants, and even a few Anglicans.

Before our visit to Paris ends later today, I am taking some quiet time early this morning for reflection, prayer and reading in these ways:

1, A reflection on a French saint or writer in spirituality;

2, today’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

Simone de Beauvoir once said she envied Simone Weil for ‘having a heart that could beat right across the world’

French saints and writers: 6, Simon Weil (1909-1943):

Simone Adolphine Weil (1909-1943) was a philosopher, mystic, teacher, trade unionist and political activist. During her life, Weil became increasingly religious and inclined towards mysticism, although most of her writings did not attract much attention until after her death. By the end of the 20th century, she was widely regarded as an influential writer on religious and spiritual matters.

Simone Weil was born in Paris on 3 February 1909. Her father, Bernard Weil (1872-1955), was a medical doctor from an agnostic Jewish family who moved from Alsace to Paris after the German annexation of Alsace-Lorraine. Her mother, Salomea (Selma) Reinherz (1879-1965), was born into a Jewish family in Rostov-on-Don and grew up in Belgium.

As a teenager, she attended the Lycée Henri IV in the Latin Quarter, close to where we are staying this week. In her late teens, she became involved in the workers’ movement. She wrote political tracts, marched in demonstrations and advocated workers’ rights, and identified as a Marxist, pacifist and trade unionist.

She studied philosophy at the École Normale Supérieure, also in the Latin Quarter and where her contemporaries included Simone de Beauvoir. Later, while teaching philosophy at a girls’ school in Le Puy, she became involved in local political activity. But she never formally joined the French Communist Party and in her 20s she became increasingly critical of Marxism.

She visited Germany in 1932 to help activists, but considered them no match for the Nazis. When Hitler took power in 1933, she helped activists fleeing Germany.

She took part in the French general strike of 1933. Later that year, she arranged for Leon Trotsky to stay at her parents’ apartment in Paris and argued against him both in print and in person, suggesting that élite communist bureaucrats could be just as oppressive as the worst capitalists. She spent more than a year working as a labourer, mostly in car factories, so that she could better understand the working class.

Although she was born into a secular household and raised in agnosticism, from 1935 Simon Weil was attracted to Christianity. The first of three pivotal religious experiences was being moved by the beauty of villagers singing hymns in a procession she saw during a holiday in Portugal.

Despite her professed pacifism, she travelled to the Spanish Civil War in 1936 to join the Republicans, and joined the anarchist Durruti Column. But she was clumsy and near-sighted and after a few weeks burnt herself over a cooking fire. Her parents followed her to Spain, and helped her leave to recuperate in Assisi. A month later, her unit was almost wiped out at Perdiguera in October 1936, and every woman in the group was killed.

While she was in Assisi in the spring of 1937, she experienced a religious ecstasy in the Basilica of Santa Maria degli Angeli, the church where Saint Francis of Assisi had prayed. There she felt compelled to kneel and she prayed for the first time in her life.

She was attracted to Catholicism, spent Holy Week and Easter in 1938 in the Benedictine abbey in Solesmes. There she had a third, more powerful revelation while reciting George Herbert’s poem Love III, after which ‘Christ himself came down and took possession of me.’

She was completely unprepared for this encounter with Christ. Having never read the mystics, she had never conceived of the possibility of a ‘real contact, person to person, here below, between a human being and God. This experience led her to rethink many of her intellectual positions, and also raised the question of baptism.

From then on, her writings became more mystical and spiritual, but retained their focus on social and political issues. But she decided not to be baptised at the time, preferring to remain outside due to ‘the love of those things that are outside Christianity.’

During World War II, she lived for a time in Marseille, receiving spiritual direction from Joseph-Marie Perrin, a Dominican Friar. At that time, she also met the French Catholic writer Gustave Thibon, who later edited some of her work. She was also interested in other religious traditions, including the Greek and Egyptian mysteries, the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita in Hinduism, and Mahayana Buddhism.

Although she was reluctant to leave France, Simone Weil travelled to the US with her family in 1942 for the sake of her parents’ safety; As Jews, they were in danger under the Vichy regime. She lived in an apartment Riverside Drive from July to November, and then returned to Europe to join the French Resistance in London. She was assigned to desk work in London, but this gave her time to write one of her best-known works, The Need for Roots.

She may have been recruited by the Special Operations Executive, with plans to send her back to France as a clandestine wireless operator. Preparations were underway in May 1943 to send her to Thame Park in Oxfordshire for training. But the plan was cancelled soon after, as her failing health became known.

Towards the end of her life, she was working on a tragedy, Venice Saved. The play explores the realisation of her own thoughts on tragedy. The play depicts the plot by a group of Spanish mercenaries to sack Venice in 1618 and how it fails when one conspirator, Jaffier, betrays them to the Venetian authorities, because he feels compassion for the city’s beauty.

The central character is a figure of affliction, a central theme in her religious metaphysics. The play offers a unique insight into her broader philosophical interest in truth and justice.

She was diagnosed with tuberculosis, started to eat less, and even refused food on many occasions. She was probably baptised during this period. As her health quickly deteriorated, she was moved to a sanatorium at Grosvenor Hall in Ashford, Kent, and she died on 24 August 1943 from cardiac failure at the age of 34. The coroner’s report said she had killed herself ‘by refusing to eat whilst the balance of her mind was disturbed.’ Others more kindly say ‘she died of an excess of love.’

Simone Weil's best-known works were published posthumously. It has been said she ‘was maybe the greatest example of living one’s philosophy that has ever existed.’

Maurice Schumann said that since her death there was ‘hardly a day when the thought of her life did not positively influence his own and serve as a moral guide.’ Albert Camus described her as ‘the only great spirit of our times.’ Simone de Beauvoir once said she envied her for ‘having a heart that could beat right across the world.’

In the aftermath of 9/11, Archbishop Rowan Williams, noted the importance of Simon Weil’s concept of ‘the void,’ calling it a ‘breathing space,’ a moment, created by catastrophe, when we are open to God and others. Like her, Archbishop Williams believes that all too often we waste these moments by filling them up with our attempts to make God fit our agendas, in religious language that is ‘formal or self-serving.’

In Waiting for God, Simone Weil says the three forms of implicit love of God are: love of neighbour; love of the beauty of the world; and love of religious ceremonies. Love of neighbour occurs when the strong treat the weak as equals, when people give personal attention to those that otherwise seem invisible, anonymous, or non-existent, and when people look at and listen to the afflicted as they are, without explicitly thinking about God.

Simone Weil recalled that after reading George Herbert’s poem Love III ‘Christ himself came down and took possession of me’

Mark 7: 24-30 (NRSVA):

24 From there he set out and went away to the region of Tyre. He entered a house and did not want anyone to know he was there. Yet he could not escape notice, 25 but a woman whose little daughter had an unclean spirit immediately heard about him, and she came and bowed down at his feet. 26 Now the woman was a Gentile, of Syrophoenician origin. She begged him to cast the demon out of her daughter. 27 He said to her, ‘Let the children be fed first, for it is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs.’ 28 But she answered him, ‘Sir, even the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs.’ 29 Then he said to her, ‘For saying that, you may go – the demon has left your daughter.’ 30 So she went home, found the child lying on the bed, and the demon gone.

Albert Camus described Simone Weil as ‘the only great spirit of our times’

Today’s Prayers (Thursday 8 February 2024):

The theme this week in ‘Pray With the World Church,’ the Prayer Diary of the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel), is ‘Gender Justice in Christ.’ This theme was introduced on Sunday by Ellen McMibanga, Zambia Anglican Council Outreach Programme.

The USPG Prayer Diary today (8 February 2024) invites us to pray in these words:

Thank you, Lord, that we have been made equally by you. May we be unwavering in our support for establishing and upholding justice in our homes, churches and communities.

The Collect:

Almighty God,

you have created the heavens and the earth

and made us in your own image:

teach us to discern your hand in all your works

and your likeness in all your children;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who with you and the Holy Spirit reigns supreme over all things,

now and for ever.

The Post-Communion Prayer:

God our creator,

by your gift

the tree of life was set at the heart of the earthly paradise,

and the bread of life at the heart of your Church:

may we who have been nourished at your table on earth

be transformed by the glory of the Saviour’s cross

and enjoy the delights of eternity;

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

Additional Collect:

Almighty God,

give us reverence for all creation

and respect for every person,

that we may mirror your likeness

in Jesus Christ our Lord.

Yesterday’s Reflection (Canon Frederic Anstruther Cardew, 1866-1942)

Continued Tomorrow (André and Magda Trocmé)

In her dying weeks, Simone Weil was working on ‘Venice Saved’, a play exploring her interests in truth and justice

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)