‘The Sign of the Bible’ at No 35 Stonegate, York, was the family home and worshop of John Ward Knowles (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Patrick Comerford

John Ward Knowles (1838-1931) was a talented York-based stained-glass manufacturer and glazier at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, and a commentator on local art and music.

Knowles is particularly known for his restoration of ‘The ‘Pricke of Conscience’ window in All Saints’ Church, North Street, in 1861 at the start of his long career, and he re-leaded the window in 1877. I am looking at the story of this window in my reflections in my prayer diary each morning for three days – today, tomorrow and Tuesday.

Knowles – appropriately, it seems to me – worked from a house known ‘The Sign of the Bible’ at No 35 Stonegate, York.

John Ward Knowles was born in York in 1838, and after his training moved in 1869 to premises at The Star Inn, No 41 Stonegate, previously the house of a hosier named Robinson.

The Olde Starre Inn, in one of the alleys off Stonegate, claims to be the oldest public house in York and dates back to 1644, the year of the Parliamentarian siege of York. The ‘old star’ is said to be King Charles I. The Cromwellians used the tenth century cellar as a hospital and a mortuary during the Civil War.

Knowles moved into No 35 Stonegate after he and Jane Annakind were married in 1874, and this remained the Knowles family home for the 120 years.

The chained printer’s devil at No 33 Stonegate is a traditional symbol of a printer (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Stonegate runs north east from Saint Helen’s Square to Petergate, and is one of the most architecturally varied streets in York. The name Stonegate first appears on records in 1118. Around 2 metres below the street’s pavement lies the Roman Via Praetoria, which connected the basilica at the centre of the fortress to the bridge over the River Ouse and the civilian settlement on the other side of the river.

From mediaeval times, the top of the street was under the jurisdiction of York Minster and was home to trades and crafts such as goldsmiths, printers and glass painters.

The chained red devil high up on the wall outside No 33 Stonegate is a traditional symbol of a printer. The printer’s devils were boys who used to fetch and carry type.

Mulberry Hall at 17-19 Stonegate dates from 1434 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Another curious house on the street, Mulberry Hall at 17-19 Stonegate, dates from 1434. Almost 600 years old, this timber framed building has been a shop since the 18th century and until 2016 was a prominent china and porcelain shop. Since then it has been occupied by a year-round Christmas shop.

A sign on the street indicates the way to Coffee Yard, next to Mulberry Hall. There the writer and publisher Thomas Gent had his premises in the 18th century. Gent wrote one of the first histories of York and married into a printing family, but ruined the business after repeatedly arguing with many of his customers, including the Dean and Chapter of York.

The York Archaeological Society examined the buildings in Coffee Yard in the 1980s prior to development, and discovered the remains of a 14th century building beneath the relatively modern façade of a derelict office block.

This was first built as a hostel for the monks of Nostell Priory, near Wakefield, ca 1360. The building was rebuilt as it might have appeared in 1483, and was named Barley Hall after the chair of York Civic Trust, Professor Maurice Barley.

The Golden Bible at No 35, dated 1682 … a traditional sign for a bookshop (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

The home JW Knowles acquired at No 35 Stonegate had been a bookshop since 1682. The earliest part of the house facing onto Stonegate is a three-storey, timber-framed range built in the 15th century.

The Golden Bible, dated 1682, hangs above the doorway of No 35. This is a traditional sign for a bookshop. In the 17th century, a two-storey, timber-framed building, was built at the rear, possibly as a workshop. The courtyard that separated the two ranges was filled in ca 1700 with a brick-built link block.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the shop was said to be York’s premier bookshop. The ‘Sign of the Bible’ also had a printing press and in 1759 John Hinxman published the first two volumes of Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy.

The young Princess Victoria of Kent, visited No 35 Stonegate in September 1835, and it is said the future Queen Victoria took tea in the back parlour.

After Knowles moved into No 35 in 1874, he began to renovate the building that became a hub of artistic endeavour with workshops producing stained glass and other kinds of church decoration, including beautiful embroideries and tapestry work produced by his daughters.

Knowles created a confection of Victorian Tudor detailing on the façade of No 35. But, apart from the jettying and the gable on to Stonegate, his creation bore little relation to the original 15th century building. Every surface is covered with ornament and the date of 1682 has been added, the year that Francis Hildyard opened his bookshop, ‘The Sign of the Bible.’

Although much of the original 17th and 18th century interior remains, including a number of panelled rooms and a fine staircase, the blend of historic fabric and 19th century interventions are distinctly Victorian.

The house has a large collection of stained glass, some of it in the upper panels in the ground-floor shopfront and in the oriel window on the first floor.

Three women saints – Saint Barbara, Saint Cecilia and Saint Agnes – in a window by JW Knowles (1891) in Saint Olave’s Church, York (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Knowles’s major works include the restoration of the Saint Cuthbert Window in York Minster in 1887, when he created 10 of the 75 episodes from the life of the saint. His other important commissions can be seen in many York churches, including Saint Olave’s, Saint Lawrence’s, and Saint Margaret’s.

The mediaeval Saint Lawrence was demolished leaving only its tower now stands in the church yard. JG Hall of Canterbury designed an ambitious new church, built in 1881-1883. The church contains a large collection of late 19th and early 20th century stained glass, much of it by Knowles, including three windows in the apse (1895) and the north transept window (1906). His windows in Saint Margaret, Walmgate, date from 1926 and 1930.

Knowles continued to live at No 35 Stonegate and to work in stained glass until he died at the age of 93 in 1931. No 35 retains much of Knowles’s work, including a collection of priceless late Victorian and Edwardian stained glass.

His sons continued the business until 1953. In the spirit of the Arts and Crafts movement of William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, JW Knowles & Sons carried out all forms of decorative work for churches, including embroidery and tapestries created by his daughters. It became York’s leading firm of glass painters, stained glass restorers and church decorators.

John Ward’s son, John Alder Knowles (1881-1961), continued the family business in the 1930s. Before the outbreak of World War I, he researched glass-manufacturing methods in North America, including the work of Louis Comfort Tiffany, who made Art Nouveau stained glass windows and electric lamps with multi-coloured stained-glass shades. Back in York, he joined the family firm in 1912. He produced some prototype Tiffany-style lamps but they were never a commercial success.

JA Knowles was active in the British Society of Master Glass-Painters and edited the Journal of Stained Glass (1926-1939) and Essays in the History of the York School of Glass-painting. The stained-glass workshop closed in 1953, although the property remained in the family until 1999.

The archives of JW Knowles & Son have been the Borthwick Institute at the University of York since 1977, with further additions in 1991, 1999 and 2008. The archives also contain the research papers of John Alder Knowles.

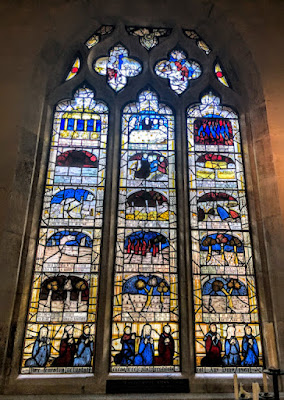

‘The Pricke of Conscience’ window, depicting the 15 signs of the End of the World – the most important mediaeval stained glass in All Saints’ Church, North Street, York – was restored by JW Knowles and is the subject of my prayer diary these mornings (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

09 October 2022

Praying in Ordinary Time with USPG:

Sunday 9 October 2022

‘The Pricke of Conscience’ window, depicting the 15 signs of the End of the World … the most important mediaeval stained glass in All Saints’ Church, North Street, York (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022; click on images for full-screen viewing)

Patrick Comerford

Today is the Seventeenth Sunday after Trinity (Trinity XVII). Later this morning, I hope to attend the Parish Eucharist in the Church of Saint Mary and Saint Giles in Stony Stratford.

But, before today gets busy, I am taking some time this morning for reading, prayer and reflection.

During the last two weeks, I was reflecting each morning on a church, chapel, or place of worship in York, where I stayed in mid-September. This week I am reflecting on the windows in one of those churches: All Saints’ Church, North Street, York.

In my prayer diary this week I am reflecting in these ways:

1, One of the readings for the morning;

2, A reflection on the windows in All Saints’ Church, North Street, York;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary, ‘Pray with the World Church.’

The north aisle and Lady Chapel in All Saints’ Church contains the early 15th century window depicting ‘The Pricke Of Conscience’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022; click on images for full-screen viewing)

Luke 17: 11-19 (NRSVA):

11 On the way to Jerusalem Jesus was going through the region between Samaria and Galilee. 12 As he entered a village, ten lepers approached him. Keeping their distance, 13 they called out, saying, ‘Jesus, Master, have mercy on us!’ 14 When he saw them, he said to them, ‘Go and show yourselves to the priests.’ And as they went, they were made clean. 15 Then one of them, when he saw that he was healed, turned back, praising God with a loud voice. 16 He prostrated himself at Jesus’ feet and thanked him. And he was a Samaritan. 17 Then Jesus asked, ‘Were not ten made clean? But the other nine, where are they? 18 Was none of them found to return and give praise to God except this foreigner?’ 19 Then he said to him, ‘Get up and go on your way; your faith has made you well.’

The three panels at the base of the ‘Pricke of Conscience’ window depict the donors, the Henryson and Hessle families, prominent families in York who were related by marriage (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022; click on images for full-screen viewing)

‘The Pricke of Conscience’ window, All Saints Church, York (Part 1):

All Saints’ Church, North Street, York, which I described in this prayer diary recently (28 September 2022), is said to be ‘York’s finest mediaeval church.’ It dates from the 11th century and stands near the River Ouse.

The church has an important collection of mediaeval stained glass, including ‘The Pricke of Conscience’ window, depicting the 15 signs of the End of the World; the window depicting the Corporal Works of Mercy (see Matthew 25: 31ff); the Great East Window, originally in the north wall; the Lady Chapel Window; the Saint James the Great Window; the Saint Thomas Window; and the Coats-of-Arms window.

All Saints’ Church, on North Street, York, is known particularly for the early 15th century window depicting ‘The Pricke Of Conscience’ or ‘The Fifteen Signs of Doom’ Window, which I am looking at on these three days (Sunday, Monday and Tuesday).

This remarkable stained-glass or painted window is near the east end of the north aisle in All Saints’ Church. It consists of three lights with six image panels in each light, totalling 18 panels. There is light tracery also above.

The window dates from ca 1410-1420 and is based on an anonymous 14th century Middle English poem, ‘The Pricke of Conscience.’ The poem describes the final 15 days of the world, each panel contributing to a paraphrase of the poem.

The bottom-most row of three panels features the donors of the window, members of the Henryson and Hessle families who paid for the window. They were prominent families in York and were related by marriage. The other 15 panels depict the signs of the end of days – the countdown to the Apocalypse or Last Judgment of humanity.

This window is a fine example of the growing wealth and education of families in England in the early 15th century. The inscriptions are in Middle English and not in Latin. It is interesting that such literacy and literature was embedded in a painted window.

A knowledge of the poem and an ability to read English were needed to appreciate the window, which may suggest a degree of educational and social elitism. But the window could also have even been used as an aid in developing literacy.

Parishioners would have been familiar with the 15 signs of the end of the world and the images would be well known and recognisable. Indeed, it also teaches responsibility towards society, and it tells people that all are equal at the Last Judgment and to reflect on this earthly life.

The window was carefully restored in the 19th century by the talented York-based stained-glass manufacturer and glazier, John Ward Knowles (1838-1931), also a commentator on local art and music.

Knowles restored this window in 1861 at the start of his long career, and re-leaded it in 1877. He worked from ‘The Sign of the Bible’ at No 35 Stonegate. Following his marriage to Jane Annakind in 1874, this was the Knowles family home for the 120 years. He renovated the building which became a hub of artistic endeavour with workshops producing stained glass and other kinds of church decoration, including beautiful embroideries and tapestry work produced by the Knowles daughters.

The building still retains much of Knowles’s work, including a collection of priceless late Victorian and Edwardian stained glass. Knowles continued to live and work there until he died at the age of 93 in 1931. His sons continued the business until 1953.

‘The Pricke of Conscience’ window in All Saints’ Church was cleaned again in 1966. However, many of the inscriptions for each scene in the window have been lost over time.

The full window consists of three lights with 18 panels arranged in six equal rows.

The three panels at the base of the window depict the donors, the Henryson and Hessle families, who were prominent families in York and were related by marriage. These kneeling figures include William Hessle with his mother and father. He was a judge who was made a Baron of the Exchequer in 1421.

These donors then believed the world was going to end in the year 1500, and the positions of their faces and hands express shock and terror at the sequence of events at the Last Judgment.

The panelling behind them is painted with golden stars, indicating the style of interior decoration in churches in the early 15th century.

The inscription below the donors appears to date from the 19th century restoration.

Above the panel at the base of the window depicting the donors, there are 15 panels in five rows illustrating the poem. Reading from left to right, and from bottom to top, the first nine panels illustrate the physical destruction of the earth, while the last six panels in the window are concerned with ‘The death of All Living Things and the Fate of Humanity.’

I plan to look at these 15 panels in my reflections tomorrow (Monday) and the day after (Tuesday).

The faces and hands of the donors of ‘The Pricke of Conscience Window’ express their shock and terror at the events of the Last Judgment (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022; click on images for full-screen viewing)

Today’s Prayer (Sunday 9 October 2022, Trinity XVII):

The Collect:

Almighty God,

you have made us for yourself,

and our hearts are restless till they find their rest in you:

pour your love into our hearts and draw us to yourself,

and so bring us at last to your heavenly city

where we shall see you face to face;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

The Post Communion Prayer:

Lord, we pray that your grace

may always precede and follow us,

and make us continually to be given to all good works;

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

The theme in the USPG Prayer Diary this week is ‘Day of the Girl Child.’ This theme is introduced this morning by the Revd Benjamin Inbaraj, Director of the CSI-SEVA department, which runs the Church of South India’s social ministries. He writes:

Indian society has historically suppressed the social and economic development of girls. It is in this context that the CSI has launched the campaign for girl children. The Church, as a pioneering movement of the Kingdom of God, must dedicate itself to this cause.

The Church of South India’s Focus 9/99 programme trains clergy and congregations in child rights and child protection. We also make sure to listen to the voices of young children, both boys and girls. One recent example of this is our Children’s Synod. As part of the CSI’s Platinum Jubilee celebrations, we held a two-day event for children from across South India. Around 300 children took part in the Synod, discussing important topics like how they would like to participate in church, Sunday school and educational institutions. The children then gave recommendations to church representatives on these subjects, which will feed into a conference on Child-Friendly Churches.

To support the work of USPG’s church partners, visit www.uspg.org.uk/donate

The USPG Prayer Diary invites us to pray today in these words:

Joyful God,

let us give praise and thanks

for the wonders of your creation.

May we give thanks for all you provide.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

William Hessle kneeling in prayer with his mother and father … he became a Baron of the Exchequer in 1421 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022; click on images for full-screen viewing)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Further reading:

AB Barton, A Guide to the Church of All Saints, North Street, York (York, nd, post-2000).

Mary Chisholm, ‘All Saints’ Church, York: Pricke Of Conscience Window – Morality In Stained Glass 15th-C Style,’ Exploring Building History, <https://www.exploringbuildinghistory.co.uk/all-saints-york-pricke-of-conscience-window-morality-in-stained-glass-15th-c-style/> [Accessed 5 October 2022].

EA Gee, ‘The Painted Glass of All Saints’ Church, North Street, York’, Archaeologia 102 (1969), pp 158-162.

‘Pricke of Conscience Window’, The Stained Glass of All Saints, All Saints’ Church, North Street, York <https://www.allsaints-northstreet.org.uk/stainedglass.html> [accessed 5 October 2022].

Roger Rosewell, ‘The Pricke of Conscience of the Fifteen Signs of Doom Window in the Church of All Saints, North Street, York’, Vidimus, Issue 45 <https://vidimus.org/issues/issue-45/feature/> [accessed 5 October 2022].

The panelling behind the donors is painted with golden stars, indicating interior decoration in the early 15th century (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022; click on images for full-screen viewing)

Patrick Comerford

Today is the Seventeenth Sunday after Trinity (Trinity XVII). Later this morning, I hope to attend the Parish Eucharist in the Church of Saint Mary and Saint Giles in Stony Stratford.

But, before today gets busy, I am taking some time this morning for reading, prayer and reflection.

During the last two weeks, I was reflecting each morning on a church, chapel, or place of worship in York, where I stayed in mid-September. This week I am reflecting on the windows in one of those churches: All Saints’ Church, North Street, York.

In my prayer diary this week I am reflecting in these ways:

1, One of the readings for the morning;

2, A reflection on the windows in All Saints’ Church, North Street, York;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary, ‘Pray with the World Church.’

The north aisle and Lady Chapel in All Saints’ Church contains the early 15th century window depicting ‘The Pricke Of Conscience’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022; click on images for full-screen viewing)

Luke 17: 11-19 (NRSVA):

11 On the way to Jerusalem Jesus was going through the region between Samaria and Galilee. 12 As he entered a village, ten lepers approached him. Keeping their distance, 13 they called out, saying, ‘Jesus, Master, have mercy on us!’ 14 When he saw them, he said to them, ‘Go and show yourselves to the priests.’ And as they went, they were made clean. 15 Then one of them, when he saw that he was healed, turned back, praising God with a loud voice. 16 He prostrated himself at Jesus’ feet and thanked him. And he was a Samaritan. 17 Then Jesus asked, ‘Were not ten made clean? But the other nine, where are they? 18 Was none of them found to return and give praise to God except this foreigner?’ 19 Then he said to him, ‘Get up and go on your way; your faith has made you well.’

The three panels at the base of the ‘Pricke of Conscience’ window depict the donors, the Henryson and Hessle families, prominent families in York who were related by marriage (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022; click on images for full-screen viewing)

‘The Pricke of Conscience’ window, All Saints Church, York (Part 1):

All Saints’ Church, North Street, York, which I described in this prayer diary recently (28 September 2022), is said to be ‘York’s finest mediaeval church.’ It dates from the 11th century and stands near the River Ouse.

The church has an important collection of mediaeval stained glass, including ‘The Pricke of Conscience’ window, depicting the 15 signs of the End of the World; the window depicting the Corporal Works of Mercy (see Matthew 25: 31ff); the Great East Window, originally in the north wall; the Lady Chapel Window; the Saint James the Great Window; the Saint Thomas Window; and the Coats-of-Arms window.

All Saints’ Church, on North Street, York, is known particularly for the early 15th century window depicting ‘The Pricke Of Conscience’ or ‘The Fifteen Signs of Doom’ Window, which I am looking at on these three days (Sunday, Monday and Tuesday).

This remarkable stained-glass or painted window is near the east end of the north aisle in All Saints’ Church. It consists of three lights with six image panels in each light, totalling 18 panels. There is light tracery also above.

The window dates from ca 1410-1420 and is based on an anonymous 14th century Middle English poem, ‘The Pricke of Conscience.’ The poem describes the final 15 days of the world, each panel contributing to a paraphrase of the poem.

The bottom-most row of three panels features the donors of the window, members of the Henryson and Hessle families who paid for the window. They were prominent families in York and were related by marriage. The other 15 panels depict the signs of the end of days – the countdown to the Apocalypse or Last Judgment of humanity.

This window is a fine example of the growing wealth and education of families in England in the early 15th century. The inscriptions are in Middle English and not in Latin. It is interesting that such literacy and literature was embedded in a painted window.

A knowledge of the poem and an ability to read English were needed to appreciate the window, which may suggest a degree of educational and social elitism. But the window could also have even been used as an aid in developing literacy.

Parishioners would have been familiar with the 15 signs of the end of the world and the images would be well known and recognisable. Indeed, it also teaches responsibility towards society, and it tells people that all are equal at the Last Judgment and to reflect on this earthly life.

The window was carefully restored in the 19th century by the talented York-based stained-glass manufacturer and glazier, John Ward Knowles (1838-1931), also a commentator on local art and music.

Knowles restored this window in 1861 at the start of his long career, and re-leaded it in 1877. He worked from ‘The Sign of the Bible’ at No 35 Stonegate. Following his marriage to Jane Annakind in 1874, this was the Knowles family home for the 120 years. He renovated the building which became a hub of artistic endeavour with workshops producing stained glass and other kinds of church decoration, including beautiful embroideries and tapestry work produced by the Knowles daughters.

The building still retains much of Knowles’s work, including a collection of priceless late Victorian and Edwardian stained glass. Knowles continued to live and work there until he died at the age of 93 in 1931. His sons continued the business until 1953.

‘The Pricke of Conscience’ window in All Saints’ Church was cleaned again in 1966. However, many of the inscriptions for each scene in the window have been lost over time.

The full window consists of three lights with 18 panels arranged in six equal rows.

The three panels at the base of the window depict the donors, the Henryson and Hessle families, who were prominent families in York and were related by marriage. These kneeling figures include William Hessle with his mother and father. He was a judge who was made a Baron of the Exchequer in 1421.

These donors then believed the world was going to end in the year 1500, and the positions of their faces and hands express shock and terror at the sequence of events at the Last Judgment.

The panelling behind them is painted with golden stars, indicating the style of interior decoration in churches in the early 15th century.

The inscription below the donors appears to date from the 19th century restoration.

Above the panel at the base of the window depicting the donors, there are 15 panels in five rows illustrating the poem. Reading from left to right, and from bottom to top, the first nine panels illustrate the physical destruction of the earth, while the last six panels in the window are concerned with ‘The death of All Living Things and the Fate of Humanity.’

I plan to look at these 15 panels in my reflections tomorrow (Monday) and the day after (Tuesday).

The faces and hands of the donors of ‘The Pricke of Conscience Window’ express their shock and terror at the events of the Last Judgment (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022; click on images for full-screen viewing)

Today’s Prayer (Sunday 9 October 2022, Trinity XVII):

The Collect:

Almighty God,

you have made us for yourself,

and our hearts are restless till they find their rest in you:

pour your love into our hearts and draw us to yourself,

and so bring us at last to your heavenly city

where we shall see you face to face;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

The Post Communion Prayer:

Lord, we pray that your grace

may always precede and follow us,

and make us continually to be given to all good works;

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

The theme in the USPG Prayer Diary this week is ‘Day of the Girl Child.’ This theme is introduced this morning by the Revd Benjamin Inbaraj, Director of the CSI-SEVA department, which runs the Church of South India’s social ministries. He writes:

Indian society has historically suppressed the social and economic development of girls. It is in this context that the CSI has launched the campaign for girl children. The Church, as a pioneering movement of the Kingdom of God, must dedicate itself to this cause.

The Church of South India’s Focus 9/99 programme trains clergy and congregations in child rights and child protection. We also make sure to listen to the voices of young children, both boys and girls. One recent example of this is our Children’s Synod. As part of the CSI’s Platinum Jubilee celebrations, we held a two-day event for children from across South India. Around 300 children took part in the Synod, discussing important topics like how they would like to participate in church, Sunday school and educational institutions. The children then gave recommendations to church representatives on these subjects, which will feed into a conference on Child-Friendly Churches.

To support the work of USPG’s church partners, visit www.uspg.org.uk/donate

The USPG Prayer Diary invites us to pray today in these words:

Joyful God,

let us give praise and thanks

for the wonders of your creation.

May we give thanks for all you provide.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

William Hessle kneeling in prayer with his mother and father … he became a Baron of the Exchequer in 1421 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022; click on images for full-screen viewing)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Further reading:

AB Barton, A Guide to the Church of All Saints, North Street, York (York, nd, post-2000).

Mary Chisholm, ‘All Saints’ Church, York: Pricke Of Conscience Window – Morality In Stained Glass 15th-C Style,’ Exploring Building History, <https://www.exploringbuildinghistory.co.uk/all-saints-york-pricke-of-conscience-window-morality-in-stained-glass-15th-c-style/> [Accessed 5 October 2022].

EA Gee, ‘The Painted Glass of All Saints’ Church, North Street, York’, Archaeologia 102 (1969), pp 158-162.

‘Pricke of Conscience Window’, The Stained Glass of All Saints, All Saints’ Church, North Street, York <https://www.allsaints-northstreet.org.uk/stainedglass.html> [accessed 5 October 2022].

Roger Rosewell, ‘The Pricke of Conscience of the Fifteen Signs of Doom Window in the Church of All Saints, North Street, York’, Vidimus, Issue 45 <https://vidimus.org/issues/issue-45/feature/> [accessed 5 October 2022].

The panelling behind the donors is painted with golden stars, indicating interior decoration in the early 15th century (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022; click on images for full-screen viewing)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)