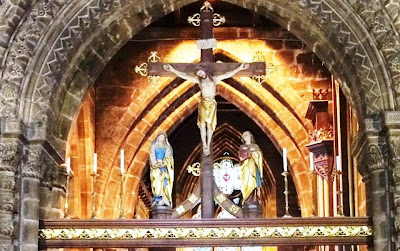

The reredos over the High Altar in Saint Chad’s was designed by William Tapper (1910) (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2014)

Patrick Comerford

One of the pleasures in travelling for work is taking an early flight at the beginning of a visit, or the last flight back, allowing an extra morning or afternoon for a walk in the countryside or along a beach, or an opportunity to visit historic churches, houses and buildings

Recently, while I was in England for the annual conference of Us, the Anglican mission agency previously known as USPG, I spent a morning in Newport, a small Essex village, photographing the old mediaeval timber-framed, pre-Tudor houses and pubs.

A few weeks earlier, I was in rural Staffordshire, researching the links between the Archbishops of Dublin and the mediaeval parish church in Penkridge, halfway between Wolverhampton and Stafford. Later in the day, as I was returning to Lichfield, I time to revisit and wander through the county town of Stafford, visiting its Tudor-era Ancient High House and two parish churches in the town centre, Saint Mary’s and Saint Chad’s

Off the beaten track

The Market Square in Stafford, a middle-size English town in the English Midlands (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2014)

Stafford is in the heart of the English Midlands, but is off the usual beaten track for Irish visitors and tourists. This middle-size English town has a population of about 56,000, making it smaller than neighbouring Staffordshire towns like Stoke-on-Trent, Tamworth, Newcastle-under-Lyme and Burton-upon-Trent, but larger than Lichfield and Cannock.

The Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy, who was born in Glasgow to Irish parents, grew up in Stafford and many of her poems describe her experiences and memories there. In 1916, JRR Tolkien, author of The Lord of the Rings, lived near Stafford, and the area around Little Haywood inspired some of his works. Stafford’s past residents also include Izaak Walton (1594-1683), author of The Compleat Angler and biographer of the Richard Hooker, George Herbert and John Donne.

The streets in the heart of Stafford have the atmosphere of a cathedral close (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2014)

The name Stafford means a river crossing by a landing place, and the town stands in the marshy valley of the River Sow, a tributary of the Trent. Stafford was probably founded around 700 by Saint Bertelin, a Mercian prince who is said to have built a hermitage close to the site of the present Collegiate Church of Saint Mary.

But the town’s civic history dates from 913, when Alfred the Great’s daughter Æthelflæd founded a new town as she and her brother, King Edward the Elder of Wessex, continued their father’s push to unify England in a single kingdom. So Stafford celebrated its 1,100th anniversary last year.

After the Norman Conquest, the region was parcelled out among the followers of William the Conqueror. Stafford and the surrounding countryside passed to Robert de Tonei, ancestor of the Stafford family, who built the castle and took their new family name from the town.

A royal charter created the Borough of Stafford in 1206 and King John endowed the new parish church as a “Royal Peculiar” with a dean and college of 13 prebendaries or canons.

The Dublin-born playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1751-1816) was MP for Stafford for quarter of a century (1780-1806). He was said to have paid the voters of Stafford five guineas each at the election in 1780, so his first speech in the House of Commons was a defence against the charge of bribery.

House in the heart of the town

The Shire Hall … Stafford’s civic history dates from 913 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2014)

Stafford Castle on a hilltop on the edge of the town is in ruins since the 19th century. In the town centre, the Shire Hall was built in 1798 as a court house and office of the Mayor and Clerk of Stafford. Today, it is houses an art gallery, with a café and library.

The Ancient High House is the largest timber-framed townhouse in England (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2014)

However, the most impressive civic building in the heart of Stafford today is the Tudor-style Ancient High House in Greengate Street, the main street. This house, now a local museum, is the largest timber-framed townhouse in England.

The Ancient High House was built in 1594 by the Dorrington family, using local oak from nearby Doxey Wood. Many of the original timbers bear carpenters’ marks that indicate the frame was pre-assembled on the ground and the joints numbered to aid on-site construction.

A copy of Sir Anthony van Dyck’s triptych of King Charles I in the Ancient High House, which became the royalist headquarters (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2014)

At the outbreak of the English Civil War, this was the townhouse of the Sneyd family of Keele Hall. Immediately after the outbreak of the Civil War, Charles I visited Stafford in 1643 and he made the High House the temporary headquarters of his royalists.

Prince Rupert fired two accurate shots at the spire of Saint Mary’s from the Ancient High House (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2014)

King Charles and his nephew, Prince Rupert of the Rhine, were guests of Captain Richard Sneyd in the house, and the king attended nearby Saint Mary’s Collegiate Church. Local lore recalls that when the king and Prince Rupert were walking in the garden of the High House, Prince Rupert fired two shots through the weather vane of Saint Mary’s to prove the accuracy of his pistol, hitting the tail of the cockerel twice.

A copy of the death warrant for King Charles I, signed by John Bradshaw, who became MP for Stafford in 1658 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2014)

Stafford later fell to the Parliamentarians, and the regicide John Bradshaw, who was a judge at the trial of Charles I, was elected MP for Stafford in 1658. Some decades later, William Howard, 1st Viscount Stafford, was beheaded in 1680 for his alleged role in the Titus Oates plot against King Charles II. The charges were false but the judgment was not reversed until 1685, five years after his execution. He was beatified as a Roman Catholic martyr by Pope Pius XI in 1929.

Two churches in one

Saint Mary’s was once two churches in one, divided by a screen (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2014)

The Ancient High House is close to both Saint Mary’s Collegiate Church and Saint Chad’s Church, which is the oldest building in Stafford today.

Saint Mary’s was once linked with Saint Bertelin’s Chapel, and the foundations of the early chapel can be seen at the west end of the church. Saint Mary’s was rebuilt in the 13th and 14th centuries in a cruciform layout with an aisled nave, chancel and clerestory.

In 1258, Roger de Meyland, Bishop of Lichfield, broke open the doors of Saint Mary’s and entered with an armed troop to claim authority over the “Royal Peculiar.” A pitched battle was fought inside the church, blood was shed and some of the canons were wounded.

Until the Reformation, Saint Mary’s was two churches in one, divided by a screen. The nave served as the parish church of Stafford while the chancel was used by the dean and the 13 canons of the College of Saint Mary whose duty was to say Mass daily for living and dead members of the royal family. The dividing screens survived the dissolution of the college in 1548 and remained until 1841.

Until 1593, the octagonal tower was topped by a spire said to be one of the highest in England. A storm that year blew it down, causing major damage to the south transept and the spire was never rebuilt. That year too, Izaak Walton was baptised in the church on 21 September 1593. He was related by marriage to both Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and the nonjuror Bishop Thomas Ken.

When Stafford fell to the Parliamentarians in 1642, Saint Mary’s became a barracks and stables. By 1777, the church was in such poor state that it was closed. Some repairs were carried out on the tower, roof, parapets and windows, but by 1837 the church was in a dilapidated condition once again. Archdeacon George Hodson demanded a full report from the churchwardens and in 1840 George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878) was commissioned to restore the church.

Scott was deeply influenced by AWN Pugin’s articles in the Dublin Review on church architecture. Pugin was working on Alton Towers and at Saint Giles in Cheadle at the time. When Scott’s restoration was completed in 1844, Pugin described it as “the best restoration which has been effected in modern times.”

In 1929, the Revd Lionel Lambert (1869-1948) challenged the authority of the Bishop of Lichfield, claiming the church was still the Royal Free Chapel of Saint Mary. The legal battle was not as bruising as the pitched battle in 1254, but the Bishop of Lichfield was victorious this time, although Lambert remained rector of Stafford until he retired in 1944.

Today, Saint Mary’s serves as the civic church of Stafford.

Stafford’s oldest building

Saint Chad’s Church is the oldest building in Stafford (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2014)

Nearby, opposite the Ancient High House and in the middle of a busy High Street, Saint Chad’s Church is the oldest building in Stafford, with a story stretching back to the 12th century, and perhaps even back to the time of Saint Chad, the first Bishop of Lichfield (669-672).

Saint Chad’s is a gateway into the past and to centuries of worship (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2014)

Saint Chad’s is a gateway into the past and to centuries of worship, and parishioners describe the church as a “hidden gem” in the centre of Stafford.

An inscription names Orm as the founder of Saint Chad’s: Orm vocatur qui me condidit (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2014)

Saint Chad’s was built about 1150-1190 and an inscription names the founder as Orm: Orm vocatur qui me condidit (“He who made me is called Orm”). Orm was a major landowner of Danish origin and the dragons in the carvings are a pun on his name “Orm” or “Worm.”

The dragons in the carvings are a pun on the Danish name of Orm, the founder of Saint Chad’s (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2014)

The chief glory of Saint Chad’s is the western crossing arch with its five orders of chevrons and beakheads, dating from ca 1150. The main part of the church is richly decorated, and the church preserves some important Norman carvings with unique features.

The carvings may be the work of stonemasons from the Middle East, and local legends tell of Saracen stonemasons in Staffordshire and the ‘Black Men’ of Biddulph (Photographs: Patrick Comerford, 2014)

The carvings in the archways and on the pillars may be the work of stonemasons from the Middle East who came to England during the Crusades. Local legends tell of Saracen stonemasons in Staffordshire and the “Black Men” of Biddulph. There are similarities to carvings on the pilgrim route to Santiago de Compostela and architectural historians see Moorish influences. Several foliate faces or “Green Men” illustrate the new fascination with nature and the changing ideas of the times when the church was built.

The ‘Green Men’ in Saint Chad’s illustrate a new fascination at the time the church was built (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2014)

Much of this stonework was covered up in the 17th and 18th centuries as the church was given a neo-classical style.

The Norman decorations were rediscovered when Saint Chad’s was restored from a forgotten and ruinous state in the mid-19th century. The restoration was carried out by Henry Griffiths, Robert Ward and George Gilbert Scott, who also built the Norman-Romanesque front and donated the statue of Saint Chad in the central niche. At the same time, Scott was carrying out extensive restorations of Lichfield Cathedral.

The furnishings and decorations in Saint Chad’s include a beautiful reredos over the High Altar designed by William Tapper (1910) and a rood beam with a large crucifix and figures of the Virgin Mary and Saint John (1922).

The architectural historian, Sir Nikolaus Pevsner, was never quite satisfied with Scott’s work on these two churches. But Saint Mary’s and Saint Chad’s remain landmarks in the heart of Stafford.

As I caught the bus from Stafford back through Rugeley to Lichfied, I was impressed how these churches stand as witnesses to the faith of their founders and a testament to those who built and maintained them and worshiped in Stafford throughout the ages.

The rood beam in Saint Chad’s, with a large crucifix and figures of the Virgin Mary and Saint John (1922) (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2014)

Canon Patrick Comerford is Lecturer in Anglicanism, Liturgy and Church History, the Church of Ireland Theological Institute. This essay and these photographs were first published in August 2014 in the Church Review (Dublin and Glendalough).

03 August 2014

‘Among the calamities of war may be justly

numbered the diminution of the love of truth’

The Feeding of the Multitude … a modern Coptic icon

Patrick Comerford

Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin

3 August 2014

The Seventh Sunday after Trinity

11 a.m.: The Cathedral Eucharist

Readings:

Isaiah 55: 1-5; Psalm 145: 8-9, 15-22; Romans 9: 1-5; Matthew 14: 13-21.

May I speak to you in the name of + the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit, Amen.

This morning’s Gospel reading (Matthew 14: 13-21) is so familiar that – like all familiar stories – we sometimes become immune to its impact and its implications.

It is so familiar perhaps because this story, the First Feeding Miracle or the “the Feeding of the 5,000,” is the only miracle found in each of the four Gospels (Matthew 14: 13-21; Mark 6:31-44; Luke 9: 10-17; and John 6: 5-15).

In addition, there is a second feeding miracle, “The Feeding of the 4,000,” found only in this Gospel (Matthew 15: 32-39) and in Saint Mark’s Gospel (Mark 8: 1-9), but not in Saint Luke’s or Saint John’s.

In the first feeding miracle in Saint Matthew’s Gospel, Christ feeds 5,000 with five loaves and two fish (Matthew 14: 17), and in the second miracle 4,000 are fed with seven loaves and a few small fish (see Matthew 15: 34).

When the Early Church read these Gospel stories of the feeding of the multitudes, they too would have shared other familiar images that shaped how they responded.

They would have thought how Christ frequently refers to himself as bread: “the true bread from heaven” (John 6: 32), “the bread of God” (John 6: 33), “the bread of life” (John 6:35, 48), and “the living bread that came down from heaven. Whoever eats of this bread will live forever; and the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh” (John 6: 51).

This morning’s reading is filled with Eucharistic symbolism: Christ takes, blesses, breaks and gives the bread, just as at the Last Supper, when he takes, blesses, breaks and gives the bread, saying: “Take, eat; this is my body” (Matthew 26: 26).

But in reading about the feeding in the wilderness, early Christians would also recall the Feeding in the Wilderness in the Exodus story.

The slaves who are liberated and flee tyranny in Egypt, cross through the waters of the Red Sea and find themselves wandering in the wilderness, relying on God miraculously for food (see Exodus 16; Deuteronomy 8: 3-16; Psalm 78: 24-25; Psalm 105: 40; Wisdom 16: 20-21).

The image of God who hears the cry of the poor, has compassion for them, and feeds the hungry is an image of God that resonates throughout the Old Testament. It sustains the exiles in Babylon, and it informs the Psalmist, who writes this morning: “The eyes of all wait upon you, O Lord, and you give them their food in due season. You open wide your hand, and satisfy the needs of every living creature” (Psalm 145: 16-17).

These verses were so loved throughout the history of Christianity that they became the opening words of the grace in Trinity College Dublin and virtually every Cambridge and Oxford college (Oculi omnium in te sperant Domine or Oculi omnium ad te spectant, Domine).

In this morning’s Gospel, the tyrant Herod has beheaded John the Baptist, and Christ leaves, taking a boat across the water to a deserted place. Herod fears the crowds, but instead of seeking Herod they find Jesus in the deserted place on the other side of the water. And there he feeds them in the deserted place, the waste land.

We often think of deserted places and waste lands as desolate places that are life-threatening rather than life-enhancing. No wonder TS Eliot’s The Waste Land is written in the wake of the destruction and the desolation of World War I, with imagery that recalls the burial of the dead, the fire, the thunder, the water of war.

We have already embarked on a rollover of commemorations of World War I. Over the next four years, we will remember the fire and the thunder of war, and the burial of the dead, the desolation and the destruction, the sacrilegious waste of life, the dehumanisation of humanity.

World War I began on 28 July 1914 when Austria declared war on Serbia, and Ireland entered the war on 4 August when the United Kingdom declared war on Germany.

Drawing on a phrase first used by HG Wells that August, it was soon described as the war to end all wars, or in the words of Woodrow Wilson, the war to “make the world safe for democracy.”

Last Monday night, at the unveiling of the Tree of Remembrance and the opening of the “Lives Remembered” exhibition in Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, the author Jennifer Johnston reminded us “we have just been through the most terrible century and we must hope there is not another like it.”

But as Walter Lippmann wrote in Newsweek, “the delusion is that whatever war we are fighting is the war to end war.”

How long have we known that war never ends war, that war only brings the delusion of peace? The Roman orator and historian Tacitus, who lived at the time of the Gospel writers, condemns those who plunder, slaughter and steal and falsely call the result Empire, for “they make a wasteland, and they call it peace” (Auferre, trucidare, rapere, falsis nominibus imperium; atque, ubi solitudinem faciunt, pacem appellant).

Ever since, writer after writer has described war as the failure of politics, war as the failure of diplomacy. Despite World I, World War II, the Korean War, the Cold War, the Vietnam War, the Six-Day War … an endless list of wars, we continue to become embroiled in war after war: the Gulf wars, the Iraq wars, the wars in former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Sudan, Libya, Afghanistan …the wars today in Ukraine, Russia, Syria and Gaza.

I have tried to use simple math to estimate the number of people killed in war in the first 14 years of this century. It is said 20 million people died in World War I, with another two million killed in the Ottoman genocides of Greeks, Armenians and Assyrians; 55 million people were killed in World War II, including the victims of the Holocaust.

In my calculations, I lost count of the victims of war in the first 14 years of this century, but we have already passed the highest estimate for World War I, and it seems we are soon going to pass the total for World War II.

And the principle casualties, time and again, are not the failed politicians, the failed diplomats, or even the poor soldiers, but civilians, children, the young and the elderly, women and men,. And truth.

‘Among the calamities of war may be justly numbered the diminution of the love of truth’ … John Myatt’s mural of Samuel Johnson on a wall in Bird Street, Lichfield (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2013)

Æschylus, one of the three great tragic playwrights in ancient Greece, alongside Sophocles and Euripides, is sometimes attributed with saying: “In war, truth is the first casualty” (cf Romans 9: 1). However, the saying may originate with the 18th century Anglican saint, Samuel Johnson from Lichfield, who wrote: “Among the calamities of war may be justly numbered the diminution of the love of truth, by the falsehoods which interest dictates and credulity encourages” [The Idler, No 30, 11 November 1758].

Israel’s Ambassador to the US, Ron Derner, told a Christian lobby group in Washington a few days ago: “Some are shamelessly accusing Israeli of genocide and would put us in the dock for war crimes. But the truth is that the Israeli Defence Forces should be given the Nobel Peace Prize ... a Nobel Peace Prize for fighting with unimaginable restraint.”

Yet, night after night, on television screens and impartial news outlets, I see the wounded, injured, maimed and battered children, frightened, screaming and even mute in shock and terror, brought by inconsolate and despairing parents to hospitals deprived of adequate facilities and medicine.

Whoever argues that criticising Israel when it fails to be a sign of the covenant (cf Romans 9: 3-4) has never read the Old Testament prophets and their condemnations of Israel and its political leaders. These Old Testament prophets can hardly be labelled dismissively as anti-Israeli or anti-Semitic.

I am shameless in my accusations when I describe Gaza as a waste land and a wilderness. The crowds cannot flee in fear from the tyrant, for they are hemmed in and under siege, barraged by flares at night and bombarded by missiles by day, irrespective of whether they support Hamas or not, children or adults, fighters or civilians. Like the crowd in our Gospel reading, they are being told to go away. But there is nowhere for them to go, not even the sea.

The Psalmist tells us this morning that God is gracious and full of compassion (Psalm 145: 8). Christ has compassion for the people caught in the wilderness, between the tyrant and the sea (verse 14). He cures their sick (verse 14), he refuses to dismiss them (verse 16), he tells us, the Disciples, despite our pleading that we are unable to do anything (verse 17), to feed them (verse 16). And he feeds them, like the slaves fleeing tyranny are fed in the wilderness.

He feeds them with a foretaste of the Heavenly Banquet. He tells them they are counted in rather than counted out.

And in counting them, we still only count 5,000 … when the Gospel writer tells us there were 5,000 men, as well as women and children (verse 21) … 5,000, 10,000, 20,000? God’s compassion for those who are caught in the wilderness is far greater than our calculations or imaginations.

As the Prophet Isaiah reminds us this morning, “everyone who thirsts” is met with God’s compassion, even when they are without money (Isaiah 55: 1), even when they are from nations that we do not know (verse 5).

And in the midst of the desolation created by war, wars of the past that failed to end war, and wars today that are waged without compassion and create waste lands and desolation, I continue to have faith and hope.

TS Eliot ends The Waste Land with obscure words he believed were the equivalent of “The peace of God which passes all understanding” (Philippians 4: 7). I believe, as the Psalmist says this morning, that “the Lord is loving to everyone, and his compassion is over all his works … The Lord upholds all those who fall; he lifts up those who are bowed down” (Psalm 145: 9, 15).

As you respond to the invitation to the Eucharist this morning, hear Christ’s words that “the bread I will give for the life of the world is my flesh” (John 6: 51).

And so, may all we think, say and do be to the praise, honour and glory of God, + Father, Son and Holy Spirit, Amen.

Collect:

Lord of all power and might,

the author and giver of all good things:

Graft in our hearts the love of your name,

increase in us true religion,

nourish us with all goodness,

and of your great mercy keep us in the same;

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

Post Communion Prayer:

Lord God,

whose Son is the true vine and the source of life,

ever giving himself that the world may live:

May we so receive within ourselves

the power of his death and passion

that, in his saving cup,

we may share his glory and be made perfect in his love;

for he is alive and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit,

now and for ever.

Hymns (New English Hymnal):

453: Stand up! – stand up for Jesus!

302: O Thou, who at thy Eucharist didst pray

305: Soul of my Saviour, sanctify my breast

476: Ye servants of God, your Master proclaim

Canon Patrick Comerford is lecturer in Anglicanism, Liturgy and Church History, the Church of Ireland Theological Institute, and a canon of Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin. This sermon was preached at the Cathedral Eucharist on Sunday 3 August 2014.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)