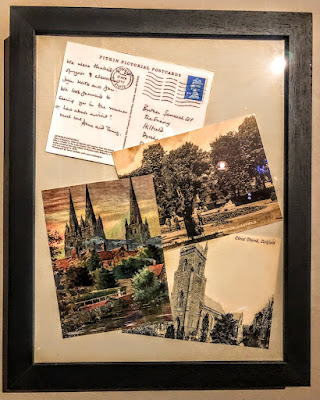

Framed postcards from Lichfield at a window in the Hedgehog Vintage Inn (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

There was a time when I sent postcards to friends and family from all my destinations, whether I was on holidays or on working trips.

And the postcards I received often ended up as bookmarks, along with theatre tickets and restaurant receipts, souvenirs of places I had visited or reminders that people had thought of me when they were away.

Two of us are in Heathrow Airport this evening, hoping to catch a plane to Budapest within the next hour or so for the first leg of a working week in Budapest and Helsinki. Charlotte and I are travelling with two other people from the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel) and the Anglican Diocese of Europe, visiting Hungary and Finland to see church-based projects working with Ukrainian refugees.

This is hardly going to be the sort of trip for sending postcards back home. But then, I think, I stopped sending postcards a long time ago. If I buy postcards these days, they are usually as keepsakes, pretty reminders of places I have visited and enjoyed.

Stamped and sent postcards are now such a rarity that they have become collectors’ items, and provide interesting discussions for local history groups.

In Lichfield, the late Dave Gallagher amassed a large collection of postcards that introduced many of the discussions on the Facebook group, ‘You’re probably from Lichfield if …’

After dinner in the Hedgehog Vintage Inn in Lichfield, I have often sat beneath two interesting collections of postcards. One collection includes a postcard showing the house in Lichfield where Samuel Johnson was born and another depicting Samuel Johnson’s statue in the Market Place.

A second collection of postcards includes Lichfield Cathedral, Beacon Gardens and Christ Church, Lichfield, and the back of one postcard has a personal message to Brother Samuel SSF, congratulating him on becoming the Guardian of Hilfield Priory in Dorchester. It is dated 17 March 1992 and signed ‘Anne and Tony.’

Sitting under those photographs in Lichfield again last summer, Charlotte quickly identified the senders of the signed postcard as Anne and Tony Barnard. This is a Pitkin postcard, and Canon Anthony Nevin (Tony) Barnard is the author of the Pitkin Guide to Lichfield Cathedral, as well as a book on Saint Chad and the Lichfield Gospels and a children’s guide to Lichfield.

Tony and Anne Barnard are now living in retirement in Barton under Needwood. I got to know them while he was the Canon Chancellor of Lichfield Cathedral and they were both involved in USPG. They were regular participants in the USPG annual conference in High Leigh and Swanwick, and we took part together in training days in Birmingham Cathedral for USPG volunteers and speakers.

When I met them again in September at the Annual Celebration and Reunion of former USPG staff and mission personnel at Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Square, I told them of how, only a few weeks earlier, Charlotte and I sat beneath the postcard they had sent from Lichfield Cathedral 30 years earlier.

They shared happy memories of visiting the Diocese of Kuching when it was twinned with the Diocese of Lichfield and of visiting Charlotte when she was placed there with USPG.

As we now head off to Budapest and Helsinki on behalf of USPG, I am thinking of how events in life can come full circle over just a few years.

Framed postcards from Lichfield at a window in the Hedgehog Vintage Inn (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Framed postcards from Lichfield at a window in the Hedgehog Vintage Inn (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

05 January 2023

Praying at Christmas through poems

and with USPG: 5 January 2023

The visit of the Magi in the sixth century Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

Christmas is not a season of 12 days, despite the popular Christmas song. Christmas is a 40-day season that lasts from Christmas Day (25 December) to Candlemas or the Feast of the Presentation (2 February).

Throughout the 40 days of this Christmas Season, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, Reflecting on a seasonal or appropriate poem;

2, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary, ‘Pray with the World Church.’

For many, the Christmas season comes to a close tomorrow with the Feast of the Epiphany. And so, for my Christmas poem this morning I have chosen ‘The Magi’ by WB Yeats.

William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) is one of the foremost figures of 20th century literature and was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival as well as a co-founder of the Abbey Theatre. He received the Nobel Prize for Literature 100 years ago in 1923 for ‘inspired poetry, which in a highly artistic form gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation.’

Yeats was the grandson and great-grandson of Church of Ireland rectors, and was named after his grandfather, the Revd William Butler Yeats (1806-1862), who died in Sandymount Castle, Dublin, a month before Christmas in 1862.

Yeats was born in 1865 at ‘Georgeville,’ 5 Sandymount Avenue, and was baptised in Saint Mary’s Church, Donnybrook. His brother Jack was a celebrated painter, while his artist sisters Elizabeth and Susan Mary – Lollie and Lily – were part of the Arts and Crafts Movement, and are buried in Saint Nahi’s Churchyard in Dundrum, Co Dublin.

The house at 10 Ashfield Terrace (now 418 Harold’s Cross Road), where WB Yeats lived during some of his schooldays (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The house at 10 Ashfield Terrace (now 418 Harold’s Cross Road), where WB Yeats lived during some of his schooldays (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Yeats was educated first in England and then at the High School in Harcourt Street, Dublin. But he spent much of his childhood in Co Sligo, which he regarded as his spiritual home. From an early age was fascinated by both Irish legends and the occult – topics that feature in the first phase of his work, although his poetry later became more physical and realistic.

In later life, Yeats largely renounced the transcendental beliefs of his youth, and in Senate debates in the 1920s he defended the place and teachings of the Church of Ireland, the Church of his birth.

He died in France in 1939 at the Hôtel Idéal Séjour, in Menton, and was buried in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. In 1948, his body was returned to Ireland and he was buried in the Church of Ireland churchyard in Drumcliffe, Co Sligo. His epitaph comes from the last lines of ‘Under Ben Bulben,’ one of his final poems:

Cast a cold Eye

On Life, on Death.

Horseman, pass by!

No 5 Woburn Walk … the Bloomsbury home of WB Yeats from 1895 to 1919 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

The ‘unsatisfied ones’

Yeats wrote the short poem ‘The Magi’ in 1914 while he was living in Bloomsbury, London. In this eight-line poem, Yeats follows the journey of the Magi or the ‘unsatisfied ones’ and their unrequited search for meaning in the ‘uncontrollable mystery on the bestial floor.’ The religious imagery in ‘The Magi’ helps to convey the themes of desire and dissatisfaction.

Although ‘The Magi’ is a short poem, its meaning is amplified by its rich diction and syntax. The magi seem almost otherworldly as they ‘appear and disappear in the blue depth of the sky’ and are constantly in the poet’s head (‘Now as at all times I can see in the mind’s eye’).

His use of repetition reinforces his imagery of the Magi, who are described twice as ‘unsatisfied’ twice (lines 2 and 7). He uses a series of ‘S’-sounding words such as: stones, stiff, still fixed, helms of silver hovering side by side, and unsatisfied. These are the characteristics of the magi, who are unchanging with ‘stiff, painted clothes.’ In religious art, the wise men are usually shown wearing fine, rich, royal clothing.

The Magi are weary and ‘pale’ with ‘ancient faces’ that resemble ‘rain-beaten stones’ and are forever waiting, ‘all their eyes still fixed, hoping to find once more’ the events that will satisfy their quest for meaning.

Yeats repeats the word ‘all’ when he describes the Magi, alluding, perhaps, to humanity as a whole: ‘With all their ancient faces’ … ‘all their helms of silver’ … ‘all their eyes still fixed.’ And, perhaps, he uses the wise men, the ‘unsatisfied ones,’ to allude to his belief that humanity has yet to discover meaning and fulfilment in Christ’s time on earth.

Christ’s first coming has left us even more dissatisfied and more fervent in our search for meaning. We cannot be fulfilled until ‘the uncontrollable mystery’ arrives, or the second coming of Christ, when the world is brought to the fulfilment of God’s promises for creation.

Yeats has the Magi not only witness the birth of Christ, but also see his death on Calvary. Yet, despite witnessing these events, they are left unfulfilled, ‘being by Calvary’s turbulence unsatisfied.’ As the wise men in ‘The Magi’ are waiting with their ‘eyes still fixed,’ upon the bright star, they are not going to be satisfied until they are led again to the ‘uncontrollable mystery on the bestial floor.’

The bestial or beastly floor is the stable in Bethlehem in the Christmas story. Or, perhaps, it is our world today. It is not the place we would expect as the birthplace of a king. The grubbiness of that stable birthplace – whether it is the stable floor or our earthly dwelling – leads to the cruelty of the crucifixion and of our world, remembered down through the centuries.

Yeats uses the plight of the magi to point out the plight in humanity. They still hopeful of find answers, hope to find the Christ Child as the answer to their quest. Is birth more fulfilling than death? Is Yeats waiting for the promise of a new birth, for himself, for Ireland, for the world? Is there a hint of apocalyptic hope, or doom?

We are all seekers, searching for the answer to this mystery, this contradiction between our hopes for divine, loving deliverance and our knowledge of the cruelties of the world and the stark reality of the human predicament. We too are Magi still searching, and the mystery continues. It may be beyond our comprehension, but our acceptance of it is the beginning of faith.

I think it is interesting to compare this poem by Yeats with TS Eliot’s ‘Journey of the Magi.’ But apart from the very different mood at the ending of each poem, the poetic imaginings are different from each other.

Yeats’s Magi are archetypal, mythic and elite figures, ‘the pale unsatisfied ones’ still searching for the meaning of ‘uncontrollable mystery on the bestial floor’ ... which some interpreters say foreshadows Christ’s Second Coming. They are ‘unsatisfied’ with the Death on Calvary and yearn back to the scene of Birth, whereas Eliot’s Magus has found the sought-for Birth ‘satisfactory.’

Yeats’s Magi seem acutely aware that something mysterious and uncontrolled and new has taken place. Yet they keep returning – at least in thought and imagination – to try to comprehend what may be incomprehensible. How is it they remain, ‘by Calvary’s turbulence unsatisfied,’ and so have to return to the mystery of the birth? On the other hand, Eliot’s Magi are more like ordinary people, complaining of the rigours of the journey, and yet pushing on to reach their goal, the preliminary goal of the ‘temperate valley,’ full of symbols, but yielding no information. They still push onwards, arriving

… at evening, not a moment too soon

Finding the place; it was (you may say) satisfactory.

But then there are those final lines, the end of their old ways and old privileges:

this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

And yet one writes:

I would do it again but …

Yeats’s Magi hope to find the mystery underlying the coming turbulence. But Eliot’s Magi foresee the coming turbulence, and while dreading it want what the promises it holds out.

The Adoration of the Magi, depicted in the 19th century Oberammergau altarpiece in the Lady Chapel in Lichfield Cathedral (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The Adoration of the Magi, depicted in the 19th century Oberammergau altarpiece in the Lady Chapel in Lichfield Cathedral (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The Magi, by WB Yeats

Now as at all times I can see in the mind’s eye,

In their stiff, painted clothes, the pale unsatisfied ones

Appear and disappear in the blue depth of the sky

With all their ancient faces like rain-beaten stones,

And all their helms of silver hovering side by side,

And all their eyes still fixed, hoping to find once more,

Being by Calvary’s turbulence unsatisfied,

The uncontrollable mystery on the bestial floor.

The Magi arriving at the crib outside Saint Mary’s Church, Askeaton, Co Limerick (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

USPG Prayer Diary:

The theme in the USPG Prayer Diary this week is ‘Refugee Response in Finland.’ This theme was introduced on Sunday by the Revd Tuomas Mäkipää, Chaplain at Saint Nicholas’ Anglican Church in Helsinki, who tells how a USPG grant is helping to support Ukrainian refugees.

The USPG Prayer Diary invites us to pray today in these words:

Let us pray for all who are anxious about the future. May they be comforted by God’s embracing love.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

The Adoration of the Magi … a stained glass window in the Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, Kilmallock, Co Limerick (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

Christmas is not a season of 12 days, despite the popular Christmas song. Christmas is a 40-day season that lasts from Christmas Day (25 December) to Candlemas or the Feast of the Presentation (2 February).

Throughout the 40 days of this Christmas Season, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, Reflecting on a seasonal or appropriate poem;

2, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary, ‘Pray with the World Church.’

For many, the Christmas season comes to a close tomorrow with the Feast of the Epiphany. And so, for my Christmas poem this morning I have chosen ‘The Magi’ by WB Yeats.

William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) is one of the foremost figures of 20th century literature and was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival as well as a co-founder of the Abbey Theatre. He received the Nobel Prize for Literature 100 years ago in 1923 for ‘inspired poetry, which in a highly artistic form gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation.’

Yeats was the grandson and great-grandson of Church of Ireland rectors, and was named after his grandfather, the Revd William Butler Yeats (1806-1862), who died in Sandymount Castle, Dublin, a month before Christmas in 1862.

Yeats was born in 1865 at ‘Georgeville,’ 5 Sandymount Avenue, and was baptised in Saint Mary’s Church, Donnybrook. His brother Jack was a celebrated painter, while his artist sisters Elizabeth and Susan Mary – Lollie and Lily – were part of the Arts and Crafts Movement, and are buried in Saint Nahi’s Churchyard in Dundrum, Co Dublin.

The house at 10 Ashfield Terrace (now 418 Harold’s Cross Road), where WB Yeats lived during some of his schooldays (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The house at 10 Ashfield Terrace (now 418 Harold’s Cross Road), where WB Yeats lived during some of his schooldays (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)Yeats was educated first in England and then at the High School in Harcourt Street, Dublin. But he spent much of his childhood in Co Sligo, which he regarded as his spiritual home. From an early age was fascinated by both Irish legends and the occult – topics that feature in the first phase of his work, although his poetry later became more physical and realistic.

In later life, Yeats largely renounced the transcendental beliefs of his youth, and in Senate debates in the 1920s he defended the place and teachings of the Church of Ireland, the Church of his birth.

He died in France in 1939 at the Hôtel Idéal Séjour, in Menton, and was buried in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. In 1948, his body was returned to Ireland and he was buried in the Church of Ireland churchyard in Drumcliffe, Co Sligo. His epitaph comes from the last lines of ‘Under Ben Bulben,’ one of his final poems:

Cast a cold Eye

On Life, on Death.

Horseman, pass by!

No 5 Woburn Walk … the Bloomsbury home of WB Yeats from 1895 to 1919 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

The ‘unsatisfied ones’

Yeats wrote the short poem ‘The Magi’ in 1914 while he was living in Bloomsbury, London. In this eight-line poem, Yeats follows the journey of the Magi or the ‘unsatisfied ones’ and their unrequited search for meaning in the ‘uncontrollable mystery on the bestial floor.’ The religious imagery in ‘The Magi’ helps to convey the themes of desire and dissatisfaction.

Although ‘The Magi’ is a short poem, its meaning is amplified by its rich diction and syntax. The magi seem almost otherworldly as they ‘appear and disappear in the blue depth of the sky’ and are constantly in the poet’s head (‘Now as at all times I can see in the mind’s eye’).

His use of repetition reinforces his imagery of the Magi, who are described twice as ‘unsatisfied’ twice (lines 2 and 7). He uses a series of ‘S’-sounding words such as: stones, stiff, still fixed, helms of silver hovering side by side, and unsatisfied. These are the characteristics of the magi, who are unchanging with ‘stiff, painted clothes.’ In religious art, the wise men are usually shown wearing fine, rich, royal clothing.

The Magi are weary and ‘pale’ with ‘ancient faces’ that resemble ‘rain-beaten stones’ and are forever waiting, ‘all their eyes still fixed, hoping to find once more’ the events that will satisfy their quest for meaning.

Yeats repeats the word ‘all’ when he describes the Magi, alluding, perhaps, to humanity as a whole: ‘With all their ancient faces’ … ‘all their helms of silver’ … ‘all their eyes still fixed.’ And, perhaps, he uses the wise men, the ‘unsatisfied ones,’ to allude to his belief that humanity has yet to discover meaning and fulfilment in Christ’s time on earth.

Christ’s first coming has left us even more dissatisfied and more fervent in our search for meaning. We cannot be fulfilled until ‘the uncontrollable mystery’ arrives, or the second coming of Christ, when the world is brought to the fulfilment of God’s promises for creation.

Yeats has the Magi not only witness the birth of Christ, but also see his death on Calvary. Yet, despite witnessing these events, they are left unfulfilled, ‘being by Calvary’s turbulence unsatisfied.’ As the wise men in ‘The Magi’ are waiting with their ‘eyes still fixed,’ upon the bright star, they are not going to be satisfied until they are led again to the ‘uncontrollable mystery on the bestial floor.’

The bestial or beastly floor is the stable in Bethlehem in the Christmas story. Or, perhaps, it is our world today. It is not the place we would expect as the birthplace of a king. The grubbiness of that stable birthplace – whether it is the stable floor or our earthly dwelling – leads to the cruelty of the crucifixion and of our world, remembered down through the centuries.

Yeats uses the plight of the magi to point out the plight in humanity. They still hopeful of find answers, hope to find the Christ Child as the answer to their quest. Is birth more fulfilling than death? Is Yeats waiting for the promise of a new birth, for himself, for Ireland, for the world? Is there a hint of apocalyptic hope, or doom?

We are all seekers, searching for the answer to this mystery, this contradiction between our hopes for divine, loving deliverance and our knowledge of the cruelties of the world and the stark reality of the human predicament. We too are Magi still searching, and the mystery continues. It may be beyond our comprehension, but our acceptance of it is the beginning of faith.

I think it is interesting to compare this poem by Yeats with TS Eliot’s ‘Journey of the Magi.’ But apart from the very different mood at the ending of each poem, the poetic imaginings are different from each other.

Yeats’s Magi are archetypal, mythic and elite figures, ‘the pale unsatisfied ones’ still searching for the meaning of ‘uncontrollable mystery on the bestial floor’ ... which some interpreters say foreshadows Christ’s Second Coming. They are ‘unsatisfied’ with the Death on Calvary and yearn back to the scene of Birth, whereas Eliot’s Magus has found the sought-for Birth ‘satisfactory.’

Yeats’s Magi seem acutely aware that something mysterious and uncontrolled and new has taken place. Yet they keep returning – at least in thought and imagination – to try to comprehend what may be incomprehensible. How is it they remain, ‘by Calvary’s turbulence unsatisfied,’ and so have to return to the mystery of the birth? On the other hand, Eliot’s Magi are more like ordinary people, complaining of the rigours of the journey, and yet pushing on to reach their goal, the preliminary goal of the ‘temperate valley,’ full of symbols, but yielding no information. They still push onwards, arriving

… at evening, not a moment too soon

Finding the place; it was (you may say) satisfactory.

But then there are those final lines, the end of their old ways and old privileges:

this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

And yet one writes:

I would do it again but …

Yeats’s Magi hope to find the mystery underlying the coming turbulence. But Eliot’s Magi foresee the coming turbulence, and while dreading it want what the promises it holds out.

The Adoration of the Magi, depicted in the 19th century Oberammergau altarpiece in the Lady Chapel in Lichfield Cathedral (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The Adoration of the Magi, depicted in the 19th century Oberammergau altarpiece in the Lady Chapel in Lichfield Cathedral (Photograph: Patrick Comerford) The Magi, by WB Yeats

Now as at all times I can see in the mind’s eye,

In their stiff, painted clothes, the pale unsatisfied ones

Appear and disappear in the blue depth of the sky

With all their ancient faces like rain-beaten stones,

And all their helms of silver hovering side by side,

And all their eyes still fixed, hoping to find once more,

Being by Calvary’s turbulence unsatisfied,

The uncontrollable mystery on the bestial floor.

The Magi arriving at the crib outside Saint Mary’s Church, Askeaton, Co Limerick (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

USPG Prayer Diary:

The theme in the USPG Prayer Diary this week is ‘Refugee Response in Finland.’ This theme was introduced on Sunday by the Revd Tuomas Mäkipää, Chaplain at Saint Nicholas’ Anglican Church in Helsinki, who tells how a USPG grant is helping to support Ukrainian refugees.

The USPG Prayer Diary invites us to pray today in these words:

Let us pray for all who are anxious about the future. May they be comforted by God’s embracing love.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

The Adoration of the Magi … a stained glass window in the Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, Kilmallock, Co Limerick (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)