With Charlotte Hunter during a recent visit to Dublin

Patrick Comerford

Some years ago, I wrote a paper for the journal Ruach on belonging in time and space, through family and place. Using words from John Betjeman, ‘To praise eternity in time and place,’ I discussed my own search for ‘a spirituality of place’ (‘To praise eternity in time and place … searching for a spirituality of place’ Ruach, No 4 (Michaelmas 2017), pp 50-56).

I maintain a family history website that connects me with people across the globe who share my surname and its variants, including Comerford, Commerford and Comberford. This website allows many people to develop a shared identity, not only because of a shared family name, but because they believe that they have found an identity that is rooted in time and place.

Many of us feel rootless, both in time and place. We do not know where we are because we do not know where we have come from, and so question where we are going. Despite shared cultures, that have many similar and familiar expressions, identity with place is a feeling that varies from one country to the next.

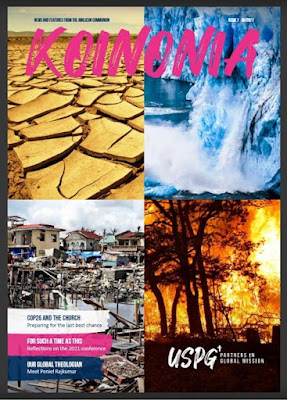

So, it was with particular personal interest that I read a feature on place and belonging that I could identify with by my dear friend Charlotte Hunter in the current edition of Koinonia (Issue 7, 10/2021, p 22), the magazine of the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel):

First Belonging – from Sarawak to England and Back

Charlotte Hunter writes of her time on USPG’s Journey with Us programme

Having been accepted on ‘Journey with Us’ in November 2015, my 12-month placement was with the Anglican Diocese of Kuching in Malaysia. It was no coincidence that I ended up in my mother’s original city. This gave me the chance to connect with the Anglican church and with my family history on a deeper level. Since then, I have chosen to stay in Kuching for several months every year, still in the neighbourhood of my mother’s birth.

My claim to being a member of the Kuching community may seem tenuous. Though a daughter of a Sarawakian-Chinese mother, I am also a product of a Northern Irish father. Though there were extended visits to Kuching as a child I was born and raised in England, and English is my mother tongue. However, in Kuching there exists for me a physical rootedness to my identity in the form of a traditional style shophouse on Carpenter Street, in the heart of the old town, from which my maternal family flows.

You may ask why this is important to me, and the answer may be that because my identity is split along the fault lines of race, culture, and continents, I’ve always felt a need for something physical, something definitive, to help me see in part who I am. This extends to the bricks and mortar of the house in which my mother was born, to the portrait of my late uncle – hung now with the photos of his parents – to my cousin at work in the family trade of watch repair, bent over his microscope as his father had done before him, and our grandfather before him, and our great grandfather before him … ‘The poetry of the everyday’, I believe it’s called.

There’s a continuity present that stretches outwards to the rest of our quarter, in particular to the thin triangle formed between the family shophouse, the temple, and Lau Ya Keng food court. The food court has been a daily part of family life reaching back to my mother's childhood, and during those extended visits, part of mine too. I now feel a deep-seated recognition of the smell of kerosene from the mobile cookers mingled with freshly brewed coffee, while the sound of torrential rain pounds on corrugated metal roofs. It was in here that my uncle and I last spoke before his final illness, where he whispered to me in his failing voice: ‘I used to bring you here for satay when you were a little girl, and now you are bringing me’.

One cousin tells me I have a tendency to romanticise life in these parts, and I fear she is right. After all, for all the familiarity there is the unfamiliarity – what the writer Amin Maalouf describes as ‘being estranged from the very traditions to which I belong’. I think about the metal grille across the front of the shophouse which, when the shop is closed, needs to be pulled back to let anyone in or out. I have never been able to manage it.

Not because it is heavy or stuck, but like a mortice key in a tricky lock, it takes a sleight of hand gained through habitude to make it shift – something I do not possess. On more pensive, introspective days, it becomes a symbol for the alienation I know exists between myself and this society in which I both belong, and cannot one hundred percent belong. I speak none of the local languages, without which no person can ever truly inhabit a society, and for all my extended childhood visits, ultimately, I was socialised in England. The consequence is that there are social and cultural complexities within both my family and the wider community which I might never understand.

Nonetheless, the feeling of belonging is stronger than any sense of non-belonging. Were anyone to ask me where my first point of identity lies, I would say right here, among these narrow streets and dark, dilapidated shophouses, in the chaos and in the heat. I would say I belong to one house in particular – the place where I’ve found the steadfastness I’ve always needed, the wellspring where four generations of my family have lived, worked, married, been born, and died. When the time comes, throw my ashes in the back yard. I’ll be home.

This is an edited version of an article first written for KINO magazine, published March 2020.

30 October 2021

Praying in Ordinary Time 2021:

154, Saint John’s Church, Wall

Saint John’s Church, Wall, stands on the site of a Roman temple dedicated to the goddess Minerva (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

Before the day begins, I am taking a little time this morning for prayer, reflection and reading. Each morning in the time in the Church Calendar known as Ordinary Time, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, photographs of a church or place of worship;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

My theme for this week is churches in Lichfield, where I spent part of the week before last in a retreat of sorts, following the daily cycle of prayer in Lichfield and visiting the chapel in Saint John’s Hospital and other churches.

In this series, I have already visited Lichfield Cathedral (15 March), Holy Cross Church (26 March), the chapel in Saint John’s Hospital (14 March), the Church of Saint Mary and Saint George, Comberford (11 April), Saint Bartholomew’s Church, Farewell (2 September) and the former Franciscan Friary in Lichfield (12 October).

This week’s theme of Lichfield churches, which I began with Saint Chad’s Church on Sunday, included Saint Mary’s Church on Monday, Saint Michael’s Church on Tuesday, Christ Church, Leomansley, on Wednesday, Wade Street Church on Thursday, and the chapel of Dr Milley’s Hospital yesterday.

This theme continues this morning (30 October 2021) with Saint John’s Church, Wall.

Saint John’s Church, Wall, was designed by WB Moffatt and Sir Gilbert Scott (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Wall is a small village just south of Lichfield, close to the A5 and the junction of the Roman roads Watling Street and Rynkild Street. Today, it is best known for the ruins of the Roman settlement at Letocetum, although it is not as well-visited as other Roman ruins throughout England.

In the first century AD, A fort was built in the upper area of the village near to the present church in 50s or 60s and Watling Street was built to the south in the 70s. By the second century, the settlement covered about 30 acres west of the later Wall Lane.

In the late third or early fourth century, the eastern part of the settlement of approximately six acres, between the present Wall Lane and Green Lane and straddling Watling Street, was enclosed with a stone wall surrounded by an earth rampart and ditches. Civilians continued to live inside the settlement and on its outskirts in the late fourth century.

The settlement declined rapidly soon after the Romans left Britain in AD 410 and the focus of settlement shifted to Lichfield. After the Romans left, Wall never developed beyond a small village.

The earliest mediaeval settlement may have been on the higher ground around Wall. Close to the church, Wall House on Green Lane probably stands on the site of the mediaeval manor house, while Wall Hall stands on the site of a 17th century house. The Trooper Inn was in business by 1851. In the 1950s, 10 council houses were built on a road called The Butts. The re-routing of the A5 around Wall, as the Wall by-pass in 1965, relieved the village of traffic, re-establishing its quiet nature.

The parish church in Wall was built in 1837 and was consecrated as the Parish Church of Saint John in 1843. The church is set at the top of a rise and is said to stand on the site of a Roman temple dedicated to the goddess Minerva, and later used for Mithraic worship. But even before the Romans, this may have been the site of Celtic temple dedicated to the god Cernunnos, who was the equivalent of the Roman Pan.

The site for the church was donated by John Mott of Wall House in 1840, along with an endowment of £700, and a further grant of £500 came from Robert Hill, a previous owner of Wall House.

The church is the work of William Bonython Moffatt (1812-1887) and his partner, the great Victorian architect Sir Gilbert Scott (1811-1878).

The church is built of pale yellow, chisel finished sandstone. There are tiled roofs on corbelled eaves with verge parapets. The church has a west steeple, nave and chancel. The steeple is a square tower of approximately three stages on a plinth with two-stage diagonal buttresses, and is chamfered in at the last stage to form an octagonal base for the short spire.

There is a single stage of small lucarnes and a small slit trefoil-headed window over the pointed west door.

The nave is of four bays on a plinth and is divided by two stage buttresses. There are two-light, square-headed trefoil-light windows to each bay.

The chancel is lower than the nave but has similar details and consists of one short bay. At the east end, there is a three-light, labelled pointed, Perpendicular-style window with panel tracery.

The interior is plain-finished, with a plastered nave, a single hammer beam and arch braced roof with double purlins and exposed rafters. There is a narrow, pointed chancel arch.

The church was built as a district chapel for the Parish of Saint Michael in Lichfield, and the finished chapel was consecrated by the Bishop of Hereford in May 1843 on behalf of the Bishop of Lichfield.

Charles Eamer Kempe (1837-1907), the Victorian stained glass designer and manufacturer, and his studios produced over 4,000 windows along with designs for altars and altar frontals, furniture and furnishings, lichgates and memorials that helped to define a later 19th century Anglican style. Many of Kempe’s works can be seen in Lichfield Cathedral, Christ Church, Lichfield, and the Chapel of Saint John’s Hospital, Lichfield. He also designed the reredos in the Lady Chapel, Lichfield.

Kempe’s window in Saint John’s Church, Wall, shows the Risen Christ meeting Mary Magdalene in the Garden on the morning of the Resurrection, and addressing her: ‘Mary.’ Peter and John who arrived at the empty tomb that Easter morning can be seen as two small figures in the background.

The dedication on the window reads: ‘To the glory of God and in loving memory of Georgina Charlotte Harrison, AD MCMIX (1909).’

South Side:

The windows on the south side, beginning at the west end, beside the entrance, depict:

1, Saint John the Baptist and the Prophet Isaiah: Both Saint John the Baptist and the Prophet Isaiah, who herald the promised coming of Christ as the Son of Man, are depicted holding staffs. The dedication reads: ‘To the glory of God & as a thank offering this window has been erected by HS and CAS.’

2, The Risen Christ meets Mary Magdalene.

3, Saint John the Divine and Saint Luke: This window may also be the work of CE Kempe. The left light shows Saint John the Evangelist holding a parchment with the opening verse of his Gospel: ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the word was with God, and the word was God.’ The window’s dedication reads: ‘To the glory of God and in loving memory of Anne Bradburne AD 1899.’

4, Saint Peter and Saint Paul: Saint Peter is on the left holding the keys of the kingdom, while his stole is inscribed with the Greek word Άγιος (‘Holy,’ ‘Saint’ or ‘Saintly’). Saint Paul, on the right, is holding a sword, the symbol of his martyrdom. The dedication reads: ‘To the Glory of God & in loving memory of the Rev W Williams, formerly vicar of this parish.’ The Revd William Williams was the Vicar of Wall for 12 years from 1864 to 1876.

The East End window:

The East Window above the altar shows Christ as the Good Shepherd. There are three sets of initials in the top of the window: Alpha (Α) and Omega (Ω), the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet, and a title of Christ in the Book of Revelation; IHS, representing the name Jesus, spelt ΙΗΣΟΥΣ in Greek capitals (Ιησουσ); and the Chi Rho symbol (XP), representing the Greek word ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ (Χριστός, Christ). On either side of Christ are the Virgin Mary (left) and Saint John the Divine (right).

The North Side:

The windows on the north side, from left to right, beginning at the west end or entrance, depict:

1, Abel and Enoch: The first window on the north side shows Abel and Enoch. Abel on the left is holding a lamb, while Enoch is one of the early prophets. The Letter to the Hebrews praises the faith of Abel and Enoch (see Hebrew 11: 4-6). The dedication reads: ‘To the glory of God & in memory of Ann Danks of Fosseway in this parish, died Sep 3 1877.’

2, Noah and Abraham: Noah (left) is holding the ark in his arms, while Abraham is holding a rather unwieldy knife representing his intended sacrifice of Isaac. This window is without any dedication or inscription.

3, Moses and Elias: This window, with Moses on the left and Elijah (or Elias) on the right has the dedication: ‘To the glory of God and in loving memory of Louisa Ann Mott & Henrietta Ley.’ Moses and Elijah represent the Law and the Prophets, and at the Transfiguration they are seen on either side of Christ.

The West End:

The two, single-light windows at the west end, at either side of the entrance, depict the Lamb of God (north) and the Holy Spirit (south).

The Church of Saint John the Baptist is at Green Lane, Wall, Staffordshire, WS14 0AS. It is uited with the Parish of Saint Michael, Greenhill. The Sunday services are normally at 10 a.m. each week. The benefice is awaiting a new rector, but in the past Sunday services have included Holy Communion on the first, second and fourth Sundays, Morning Worship on the third Sunday, and ‘Wall praise’ on the fifth Sunday, described as ‘a serviced for all the family.’

The East Window in Saint John’s Church, Wall, depicts Christ as the Good Shepherd (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Luke 14: 1, 7-11 (NRSVA):

1 On one occasion when Jesus was going to the house of a leader of the Pharisees to eat a meal on the sabbath, they were watching him closely.

7 When he noticed how the guests chose the places of honour, he told them a parable. 8 ‘When you are invited by someone to a wedding banquet, do not sit down at the place of honour, in case someone more distinguished than you has been invited by your host; 9 and the host who invited both of you may come and say to you, “Give this person your place”, and then in disgrace you would start to take the lowest place. 10 But when you are invited, go and sit down at the lowest place, so that when your host comes, he may say to you, “Friend, move up higher”; then you will be honoured in the presence of all who sit at the table with you. 11 For all who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted.’

The Risen Christ meets Mary Magdalene … a window by CE Kempe in Saint John’s Church, Wall (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (30 October 2021) invites us to pray:

We pray for those who build bridges between those of different faiths and none, and for those with whom we share a common faith in Jesus as Lord. Give us unity of mind and spirit.

Saint John the Divine and Saint Luke … this window in Saint John’s Church, Wall, may also be the work of CE Kempe (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Looking down at the Roman site of Letocetum from the West Door of Saint John’s Church, Wall, south of Lichfield (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

Before the day begins, I am taking a little time this morning for prayer, reflection and reading. Each morning in the time in the Church Calendar known as Ordinary Time, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, photographs of a church or place of worship;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

My theme for this week is churches in Lichfield, where I spent part of the week before last in a retreat of sorts, following the daily cycle of prayer in Lichfield and visiting the chapel in Saint John’s Hospital and other churches.

In this series, I have already visited Lichfield Cathedral (15 March), Holy Cross Church (26 March), the chapel in Saint John’s Hospital (14 March), the Church of Saint Mary and Saint George, Comberford (11 April), Saint Bartholomew’s Church, Farewell (2 September) and the former Franciscan Friary in Lichfield (12 October).

This week’s theme of Lichfield churches, which I began with Saint Chad’s Church on Sunday, included Saint Mary’s Church on Monday, Saint Michael’s Church on Tuesday, Christ Church, Leomansley, on Wednesday, Wade Street Church on Thursday, and the chapel of Dr Milley’s Hospital yesterday.

This theme continues this morning (30 October 2021) with Saint John’s Church, Wall.

Saint John’s Church, Wall, was designed by WB Moffatt and Sir Gilbert Scott (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Wall is a small village just south of Lichfield, close to the A5 and the junction of the Roman roads Watling Street and Rynkild Street. Today, it is best known for the ruins of the Roman settlement at Letocetum, although it is not as well-visited as other Roman ruins throughout England.

In the first century AD, A fort was built in the upper area of the village near to the present church in 50s or 60s and Watling Street was built to the south in the 70s. By the second century, the settlement covered about 30 acres west of the later Wall Lane.

In the late third or early fourth century, the eastern part of the settlement of approximately six acres, between the present Wall Lane and Green Lane and straddling Watling Street, was enclosed with a stone wall surrounded by an earth rampart and ditches. Civilians continued to live inside the settlement and on its outskirts in the late fourth century.

The settlement declined rapidly soon after the Romans left Britain in AD 410 and the focus of settlement shifted to Lichfield. After the Romans left, Wall never developed beyond a small village.

The earliest mediaeval settlement may have been on the higher ground around Wall. Close to the church, Wall House on Green Lane probably stands on the site of the mediaeval manor house, while Wall Hall stands on the site of a 17th century house. The Trooper Inn was in business by 1851. In the 1950s, 10 council houses were built on a road called The Butts. The re-routing of the A5 around Wall, as the Wall by-pass in 1965, relieved the village of traffic, re-establishing its quiet nature.

The parish church in Wall was built in 1837 and was consecrated as the Parish Church of Saint John in 1843. The church is set at the top of a rise and is said to stand on the site of a Roman temple dedicated to the goddess Minerva, and later used for Mithraic worship. But even before the Romans, this may have been the site of Celtic temple dedicated to the god Cernunnos, who was the equivalent of the Roman Pan.

The site for the church was donated by John Mott of Wall House in 1840, along with an endowment of £700, and a further grant of £500 came from Robert Hill, a previous owner of Wall House.

The church is the work of William Bonython Moffatt (1812-1887) and his partner, the great Victorian architect Sir Gilbert Scott (1811-1878).

The church is built of pale yellow, chisel finished sandstone. There are tiled roofs on corbelled eaves with verge parapets. The church has a west steeple, nave and chancel. The steeple is a square tower of approximately three stages on a plinth with two-stage diagonal buttresses, and is chamfered in at the last stage to form an octagonal base for the short spire.

There is a single stage of small lucarnes and a small slit trefoil-headed window over the pointed west door.

The nave is of four bays on a plinth and is divided by two stage buttresses. There are two-light, square-headed trefoil-light windows to each bay.

The chancel is lower than the nave but has similar details and consists of one short bay. At the east end, there is a three-light, labelled pointed, Perpendicular-style window with panel tracery.

The interior is plain-finished, with a plastered nave, a single hammer beam and arch braced roof with double purlins and exposed rafters. There is a narrow, pointed chancel arch.

The church was built as a district chapel for the Parish of Saint Michael in Lichfield, and the finished chapel was consecrated by the Bishop of Hereford in May 1843 on behalf of the Bishop of Lichfield.

Charles Eamer Kempe (1837-1907), the Victorian stained glass designer and manufacturer, and his studios produced over 4,000 windows along with designs for altars and altar frontals, furniture and furnishings, lichgates and memorials that helped to define a later 19th century Anglican style. Many of Kempe’s works can be seen in Lichfield Cathedral, Christ Church, Lichfield, and the Chapel of Saint John’s Hospital, Lichfield. He also designed the reredos in the Lady Chapel, Lichfield.

Kempe’s window in Saint John’s Church, Wall, shows the Risen Christ meeting Mary Magdalene in the Garden on the morning of the Resurrection, and addressing her: ‘Mary.’ Peter and John who arrived at the empty tomb that Easter morning can be seen as two small figures in the background.

The dedication on the window reads: ‘To the glory of God and in loving memory of Georgina Charlotte Harrison, AD MCMIX (1909).’

South Side:

The windows on the south side, beginning at the west end, beside the entrance, depict:

1, Saint John the Baptist and the Prophet Isaiah: Both Saint John the Baptist and the Prophet Isaiah, who herald the promised coming of Christ as the Son of Man, are depicted holding staffs. The dedication reads: ‘To the glory of God & as a thank offering this window has been erected by HS and CAS.’

2, The Risen Christ meets Mary Magdalene.

3, Saint John the Divine and Saint Luke: This window may also be the work of CE Kempe. The left light shows Saint John the Evangelist holding a parchment with the opening verse of his Gospel: ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the word was with God, and the word was God.’ The window’s dedication reads: ‘To the glory of God and in loving memory of Anne Bradburne AD 1899.’

4, Saint Peter and Saint Paul: Saint Peter is on the left holding the keys of the kingdom, while his stole is inscribed with the Greek word Άγιος (‘Holy,’ ‘Saint’ or ‘Saintly’). Saint Paul, on the right, is holding a sword, the symbol of his martyrdom. The dedication reads: ‘To the Glory of God & in loving memory of the Rev W Williams, formerly vicar of this parish.’ The Revd William Williams was the Vicar of Wall for 12 years from 1864 to 1876.

The East End window:

The East Window above the altar shows Christ as the Good Shepherd. There are three sets of initials in the top of the window: Alpha (Α) and Omega (Ω), the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet, and a title of Christ in the Book of Revelation; IHS, representing the name Jesus, spelt ΙΗΣΟΥΣ in Greek capitals (Ιησουσ); and the Chi Rho symbol (XP), representing the Greek word ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ (Χριστός, Christ). On either side of Christ are the Virgin Mary (left) and Saint John the Divine (right).

The North Side:

The windows on the north side, from left to right, beginning at the west end or entrance, depict:

1, Abel and Enoch: The first window on the north side shows Abel and Enoch. Abel on the left is holding a lamb, while Enoch is one of the early prophets. The Letter to the Hebrews praises the faith of Abel and Enoch (see Hebrew 11: 4-6). The dedication reads: ‘To the glory of God & in memory of Ann Danks of Fosseway in this parish, died Sep 3 1877.’

2, Noah and Abraham: Noah (left) is holding the ark in his arms, while Abraham is holding a rather unwieldy knife representing his intended sacrifice of Isaac. This window is without any dedication or inscription.

3, Moses and Elias: This window, with Moses on the left and Elijah (or Elias) on the right has the dedication: ‘To the glory of God and in loving memory of Louisa Ann Mott & Henrietta Ley.’ Moses and Elijah represent the Law and the Prophets, and at the Transfiguration they are seen on either side of Christ.

The West End:

The two, single-light windows at the west end, at either side of the entrance, depict the Lamb of God (north) and the Holy Spirit (south).

The Church of Saint John the Baptist is at Green Lane, Wall, Staffordshire, WS14 0AS. It is uited with the Parish of Saint Michael, Greenhill. The Sunday services are normally at 10 a.m. each week. The benefice is awaiting a new rector, but in the past Sunday services have included Holy Communion on the first, second and fourth Sundays, Morning Worship on the third Sunday, and ‘Wall praise’ on the fifth Sunday, described as ‘a serviced for all the family.’

The East Window in Saint John’s Church, Wall, depicts Christ as the Good Shepherd (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Luke 14: 1, 7-11 (NRSVA):

1 On one occasion when Jesus was going to the house of a leader of the Pharisees to eat a meal on the sabbath, they were watching him closely.

7 When he noticed how the guests chose the places of honour, he told them a parable. 8 ‘When you are invited by someone to a wedding banquet, do not sit down at the place of honour, in case someone more distinguished than you has been invited by your host; 9 and the host who invited both of you may come and say to you, “Give this person your place”, and then in disgrace you would start to take the lowest place. 10 But when you are invited, go and sit down at the lowest place, so that when your host comes, he may say to you, “Friend, move up higher”; then you will be honoured in the presence of all who sit at the table with you. 11 For all who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted.’

The Risen Christ meets Mary Magdalene … a window by CE Kempe in Saint John’s Church, Wall (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (30 October 2021) invites us to pray:

We pray for those who build bridges between those of different faiths and none, and for those with whom we share a common faith in Jesus as Lord. Give us unity of mind and spirit.

Saint John the Divine and Saint Luke … this window in Saint John’s Church, Wall, may also be the work of CE Kempe (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Looking down at the Roman site of Letocetum from the West Door of Saint John’s Church, Wall, south of Lichfield (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)