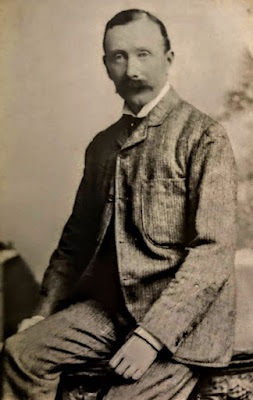

James Charles Comerford (1842-1907) of Ardavon House, Rahdrum … a contemporary of Charles Stewart Parnell, and father of Máire Comerford

Patrick Comerford

One of the presents I received this Christmas is a book I had searched for in vain in the bookshops in Limerick in recent weeks: Máire Comerford’s memoirs edited by Hilary Dully, On Dangerous Ground: A Memoir of the Irish Revolution.

This book was published a few weeks ago by Lilliput Press, and includes many of her memories, including her recollections of her branch of the Comerford family.

Máire Comerford was known as the ‘Jean d’Arc’ of Irish Republicanism and in later years she worked as a journalist with the Irish Press.

When I was in my teens, when Máire was retired and living in Saint Nessan’s in Sandyford, she was very supportive of my initial research into the history of the Comerford family. The Comerford family in Ballybur and Kilkenny and the Langton family of Kilkenny and Ballinakill were closely inter-related over many generations, and she told me how her branch of the Comerford family of Ballinakill, Co Laois, and Rathdrum, Co Wicklow, and my branch of the family from Bunclody, Co Wexford, were closely related.

Máire grew up in Co Wicklow and Co Wexford, so I have been interested in recent days to read how she recalled her family story, and her relationship with both the Comerford and the Esmonde family.

I was particularly interested in her recollection of the Comerford family history, when she recalls:

‘Our Comerford branch came to Rathdrum from Ballinakill in County Offaly [recte County Laois]. Kilkenny, like Galway, had its ‘Tribes’; but the Catholic tribes like the Walshes and the Comerfords, were evicted from the city of Kilkenny and ordered to live in Ballinakill. All this happened a very long time before our story began in Rathdrum. In a quiet way, the Comerfords belonged to a class of Irish person who seemed relatively unaffected by the Penal Laws against Catholics; people engaged in primary industries – brewers, millers, wool merchants – who thrived relative to the many Irish people who depended for their livelihood on the land and nothing else.’

Her father, James Charles Comerford (1842-1907), of Ardavon, Rathdrum, inherited the Comerford mills in Rathdrum. He grew up as a close friend of Charles Stewart Parnell, they rode horses together, they played cricket together, and James Comerford was Parnell’s election agent.

But, she recalls, ‘My mother, Eva Esmonde, was judged to have come down in the world when she married my father. On her equally Catholic but prouder side, there was a pedigree – supplied by request from the senior Esmonde family members to the editors of Debrett, and likewise to Burke …’

She describes her family as ‘Castle Catholics’ and ‘in essence West Britons.’ There is once childhood memory of being ‘ordered to the back of the class when the Irish lesson was on. I learnt what it to be a ‘West Briton’.’

When Máire’s father, James Charles Comerford, died on 3 October 1907, there was time of arbitration in the Comerford, and eventually her widowed mother, Eva Comerford, ‘brought us back to her native Wexford.’ She was the widowed mother of four children: Mary Eva (Máire), (Colonel) Thomas James Comerford (1894-1959), Dympna Helen Mulligan (1897-1977), and Alexander E (‘Sandy’) Comerford (1900-1966), later of Malahide, Co Dublin.

There are interesting accounts too of the various houses in Co Wexford where Eva Comerford lived with her young family. But perhaps more about these houses and these family stories in later postings on this blog.

• Máire Comerford, On Dangerous Ground: A Memoir of the Irish Revolution, edited by Hilary Dully (Dublin: Lilliput Press, 2021), xvii + 334 pp

28 December 2021

With the Saints through Christmas (3):

28 December 2021, the Holy Innocents

The Killing of the Holy Innocents, by Giotto (ca 1304-1306), in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

Patrick Comerford

Our Christmas celebrations continue this week, the season does not end even after the ’12 Days of Christmas.’ This is a season that continues for 40 days until the Feast of the Presentation or Candlemas (2 February).

I am in Askeaton after yesterday’s Baptism in Saint Mary’s Church, and I have started working on next Sunday’s services and sermons in Askeaton and Tarbert. But, before this day begins, I am taking some time early this morning for prayer, reflection and reading.

I am continuing my Prayer Diary on my blog each morning, reflecting in these ways:

1, Reflections on a saint remembered in the calendars of the Church during Christmas;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

It is theologically important to remind ourselves in the days after Christmas Day of the important link between the Incarnation and bearing witness to the Resurrection faith.

Saint Stephen’s Day on Sunday (26 December), Holy Innocents’ Day today (28 December), and the commemoration of Thomas à Beckett tomorrow (29 December) are reminders that Christmas, far from being surrounded by sanitised images of the crib, angels and wise men, is followed by martyrdom and violence. Close on the joy of Christmas comes the cost of following Christ. A popular expression, derived from William Penn, says: ‘No Cross, No Crown.’

The Church Calendar today (28 December) recalls the massacre of the Holy Innocents, who are sometimes revered as the first Christian martyrs. The Eastern Orthodox Church celebrates the feast tomorrow (29 December).

These dates have nothing to do with the chronological order of the event. Instead, the feast is kept within the octave of Christmas because the Holy Innocents gave their life for the new-born Saviour. Saint Stephen the first martyr (martyr by will, love and blood, 26 December), Saint John the Evangelist (27 December, martyr by will and love), and these first flowers of the Church (martyrs by blood alone) accompany the Christ Child entering this world on Christmas Day.

This commemoration first appears as a feast of the western church at the end of the fifth century, and the earliest commemorations were connected with the Feast of the Epiphany (6 January), bringing together the murder of the Innocents and the visit of the Magi.

The story of the massacre of the Innocents is the biblical narrative of infanticide by King Herod the Great (Matthew 2: 16-18). According to Saint Matthew’s Gospel, Herod ordered the execution of all young male children in the village of Bethlehem to save him from losing his throne to a new-born king whose birth had been announced to him by the Magi:

16 When Herod saw that he had been tricked by the wise men, he was infuriated, and he sent and killed all the children in and around Bethlehem who were two years old or under, according to the time that he had learned from the wise men. 17 Then was fulfilled what had been spoken through the prophet Jeremiah:

18 ‘A voice was heard in Ramah,

wailing and loud lamentation,

Rachel weeping for her children;

she refused to be consoled, because they are no more.’

In Saint Matthew’s Gospel, the visiting magi from the east arrive in Judea in search of the new-born king of the Jews, having “observed his star at its rising” (Matthew 2: 2). Herod directs them to Bethlehem, and asks them to let him know who this king is when they find him. They find the Christ Child and honour him, but an angel tells them not to alert Herod, and they return home by another way. Meanwhile, Joseph has taken Mary and the child and they have escaped to Egypt.

Saint Matthew’s Gospel provides the only account of the Massacre. This incident is not mentioned in the other three gospels, nor is it mentioned by the Jewish historian Josephus, who records Herod’s murder of his own sons. When the Emperor Augustus heard that Herod had ordered the murder of his own sons, he remarked: “It is better to be Herod’s pig, than his son.”

Saint Matthew’s story recalls passages in Hosea referring to the exodus, and in Jeremiah referring to the Babylonian exile, and the accounts in Exodus of the birth of Moses and the slaying of the first-born children by Pharaoh.

Estimates of the number of infants at the time in Bethlehem, a town with a total population of about 1,000, would be about 20. But Byzantine liturgy estimated 14,000 Holy Innocents were murdered, while an early Syrian list of saints put the number at 64,000. Coptic sources raise the number to 144,000 and place the event on 29 December.

Later, the Church of Saint Paul’s Outside the Walls in Rome was said to possess the bodies of several of the Holy Innocents. Some of these relics were transferred by Pope Sixtus V to the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore.

In many cathedrals in England, Germany and France, the boy bishops who were elected on the feast of Saint Nicholas (6 December) officiated on the feasts of Saint Nicholas and the Holy Innocents. The boy bishop wore a mitre and other episcopal insignia, sang the collect, preached, and gave the blessing. He sat in the bishop’s throne or cathedra in the cathedral while the choir-boys sang in the stalls of the canons, when they directed the choir on these two days and had their solemn procession.

The Reconciliation monument in the ruins of Coventry Cathedral … the ‘Coventry Carol’ recalls a mother’s lament for her doomed child (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

The Coventry Carol, an English Christmas carol from the 16th century and performed as part of a mystery play, depicts the Massacre of the Innocents in Bethlehem. The carol is traditionally sung a cappella, and there is a modern setting of the carol by Professor Kenneth Leighton (1929-1988).

The lyrics represent a mother’s lament for her doomed child:

Lully, lullay, Thou little tiny Child,

Bye, bye, lully, lullay.

Lullay, thou little tiny Child,

Bye, bye, lully, lullay.

O sisters too, how may we do,

For to preserve this day

This poor youngling for whom we do sing

Bye, bye, lully, lullay.

Herod, the king, in his raging,

Charged he hath this day

His men of might, in his own sight,

All young children to slay.

That woe is me, poor Child for Thee!

And ever mourn and sigh,

For thy parting neither say nor sing,

Bye, bye, lully, lullay.

Also dating from the 16th century, or perhaps even earlier from the late 14th century, is the hymn ‘Unto us is born a son.’ It has been translated by both George R Woodward and Percy Dearmer. Woodward’s version of this hymn has been sung regularly at the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols in Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin, including the third stanza:

This did Herod sore affray,

And grievously bewilder;

So he gave the word to slay,

And slew the little childer.

A detail from The Killing of the Holy Innocents, by Giotto (ca 1304-1306), in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

Matthew 2: 13-18 (NRSVA):

13 Now after they had left, an angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream and said, ‘Get up, take the child and his mother, and flee to Egypt, and remain there until I tell you; for Herod is about to search for the child, to destroy him.’ 14 Then Joseph got up, took the child and his mother by night, and went to Egypt, 15 and remained there until the death of Herod. This was to fulfil what had been spoken by the Lord through the prophet, ‘Out of Egypt I have called my son.’

16 When Herod saw that he had been tricked by the wise men, he was infuriated, and he sent and killed all the children in and around Bethlehem who were two years old or under, according to the time that he had learned from the wise men. 17 Then was fulfilled what had been spoken through the prophet Jeremiah:

18 ‘A voice was heard in Ramah,

wailing and loud lamentation,

Rachel weeping for her children;

she refused to be consoled, because they are no more.’

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (28 December 2021, The Holy Innocents) invites us to pray:

On this day, may we cherish our young people and provide them with the guidance and knowledge to navigate our complex and challenging world.

The Collect of the Day:

Heavenly Father,

whose children suffered at the hands of Herod:

By your great might frustrate all evil designs,

and establish your reign of justice, love and peace;

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

Yesterday: Saint John the Evangelist

Tomorrow: Saint Thomas Becket

A detail from the Killing of the Holy Innocents, by Giotto (ca 1304-1306), in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Patrick Comerford

Our Christmas celebrations continue this week, the season does not end even after the ’12 Days of Christmas.’ This is a season that continues for 40 days until the Feast of the Presentation or Candlemas (2 February).

I am in Askeaton after yesterday’s Baptism in Saint Mary’s Church, and I have started working on next Sunday’s services and sermons in Askeaton and Tarbert. But, before this day begins, I am taking some time early this morning for prayer, reflection and reading.

I am continuing my Prayer Diary on my blog each morning, reflecting in these ways:

1, Reflections on a saint remembered in the calendars of the Church during Christmas;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

It is theologically important to remind ourselves in the days after Christmas Day of the important link between the Incarnation and bearing witness to the Resurrection faith.

Saint Stephen’s Day on Sunday (26 December), Holy Innocents’ Day today (28 December), and the commemoration of Thomas à Beckett tomorrow (29 December) are reminders that Christmas, far from being surrounded by sanitised images of the crib, angels and wise men, is followed by martyrdom and violence. Close on the joy of Christmas comes the cost of following Christ. A popular expression, derived from William Penn, says: ‘No Cross, No Crown.’

The Church Calendar today (28 December) recalls the massacre of the Holy Innocents, who are sometimes revered as the first Christian martyrs. The Eastern Orthodox Church celebrates the feast tomorrow (29 December).

These dates have nothing to do with the chronological order of the event. Instead, the feast is kept within the octave of Christmas because the Holy Innocents gave their life for the new-born Saviour. Saint Stephen the first martyr (martyr by will, love and blood, 26 December), Saint John the Evangelist (27 December, martyr by will and love), and these first flowers of the Church (martyrs by blood alone) accompany the Christ Child entering this world on Christmas Day.

This commemoration first appears as a feast of the western church at the end of the fifth century, and the earliest commemorations were connected with the Feast of the Epiphany (6 January), bringing together the murder of the Innocents and the visit of the Magi.

The story of the massacre of the Innocents is the biblical narrative of infanticide by King Herod the Great (Matthew 2: 16-18). According to Saint Matthew’s Gospel, Herod ordered the execution of all young male children in the village of Bethlehem to save him from losing his throne to a new-born king whose birth had been announced to him by the Magi:

16 When Herod saw that he had been tricked by the wise men, he was infuriated, and he sent and killed all the children in and around Bethlehem who were two years old or under, according to the time that he had learned from the wise men. 17 Then was fulfilled what had been spoken through the prophet Jeremiah:

18 ‘A voice was heard in Ramah,

wailing and loud lamentation,

Rachel weeping for her children;

she refused to be consoled, because they are no more.’

In Saint Matthew’s Gospel, the visiting magi from the east arrive in Judea in search of the new-born king of the Jews, having “observed his star at its rising” (Matthew 2: 2). Herod directs them to Bethlehem, and asks them to let him know who this king is when they find him. They find the Christ Child and honour him, but an angel tells them not to alert Herod, and they return home by another way. Meanwhile, Joseph has taken Mary and the child and they have escaped to Egypt.

Saint Matthew’s Gospel provides the only account of the Massacre. This incident is not mentioned in the other three gospels, nor is it mentioned by the Jewish historian Josephus, who records Herod’s murder of his own sons. When the Emperor Augustus heard that Herod had ordered the murder of his own sons, he remarked: “It is better to be Herod’s pig, than his son.”

Saint Matthew’s story recalls passages in Hosea referring to the exodus, and in Jeremiah referring to the Babylonian exile, and the accounts in Exodus of the birth of Moses and the slaying of the first-born children by Pharaoh.

Estimates of the number of infants at the time in Bethlehem, a town with a total population of about 1,000, would be about 20. But Byzantine liturgy estimated 14,000 Holy Innocents were murdered, while an early Syrian list of saints put the number at 64,000. Coptic sources raise the number to 144,000 and place the event on 29 December.

Later, the Church of Saint Paul’s Outside the Walls in Rome was said to possess the bodies of several of the Holy Innocents. Some of these relics were transferred by Pope Sixtus V to the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore.

In many cathedrals in England, Germany and France, the boy bishops who were elected on the feast of Saint Nicholas (6 December) officiated on the feasts of Saint Nicholas and the Holy Innocents. The boy bishop wore a mitre and other episcopal insignia, sang the collect, preached, and gave the blessing. He sat in the bishop’s throne or cathedra in the cathedral while the choir-boys sang in the stalls of the canons, when they directed the choir on these two days and had their solemn procession.

The Reconciliation monument in the ruins of Coventry Cathedral … the ‘Coventry Carol’ recalls a mother’s lament for her doomed child (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

The Coventry Carol, an English Christmas carol from the 16th century and performed as part of a mystery play, depicts the Massacre of the Innocents in Bethlehem. The carol is traditionally sung a cappella, and there is a modern setting of the carol by Professor Kenneth Leighton (1929-1988).

The lyrics represent a mother’s lament for her doomed child:

Lully, lullay, Thou little tiny Child,

Bye, bye, lully, lullay.

Lullay, thou little tiny Child,

Bye, bye, lully, lullay.

O sisters too, how may we do,

For to preserve this day

This poor youngling for whom we do sing

Bye, bye, lully, lullay.

Herod, the king, in his raging,

Charged he hath this day

His men of might, in his own sight,

All young children to slay.

That woe is me, poor Child for Thee!

And ever mourn and sigh,

For thy parting neither say nor sing,

Bye, bye, lully, lullay.

Also dating from the 16th century, or perhaps even earlier from the late 14th century, is the hymn ‘Unto us is born a son.’ It has been translated by both George R Woodward and Percy Dearmer. Woodward’s version of this hymn has been sung regularly at the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols in Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin, including the third stanza:

This did Herod sore affray,

And grievously bewilder;

So he gave the word to slay,

And slew the little childer.

A detail from The Killing of the Holy Innocents, by Giotto (ca 1304-1306), in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

Matthew 2: 13-18 (NRSVA):

13 Now after they had left, an angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream and said, ‘Get up, take the child and his mother, and flee to Egypt, and remain there until I tell you; for Herod is about to search for the child, to destroy him.’ 14 Then Joseph got up, took the child and his mother by night, and went to Egypt, 15 and remained there until the death of Herod. This was to fulfil what had been spoken by the Lord through the prophet, ‘Out of Egypt I have called my son.’

16 When Herod saw that he had been tricked by the wise men, he was infuriated, and he sent and killed all the children in and around Bethlehem who were two years old or under, according to the time that he had learned from the wise men. 17 Then was fulfilled what had been spoken through the prophet Jeremiah:

18 ‘A voice was heard in Ramah,

wailing and loud lamentation,

Rachel weeping for her children;

she refused to be consoled, because they are no more.’

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (28 December 2021, The Holy Innocents) invites us to pray:

On this day, may we cherish our young people and provide them with the guidance and knowledge to navigate our complex and challenging world.

The Collect of the Day:

Heavenly Father,

whose children suffered at the hands of Herod:

By your great might frustrate all evil designs,

and establish your reign of justice, love and peace;

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

Yesterday: Saint John the Evangelist

Tomorrow: Saint Thomas Becket

A detail from the Killing of the Holy Innocents, by Giotto (ca 1304-1306), in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)