‘The Story of the original CMK’, reminiscences of the people who shaped Central Milton Keynes … a Christmas present (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

Patrick Comerford

One of the Christmas presents I received from Charlotte is the book The Story of the original CMK, a unique set of reminiscences by the people who shaped the initial ideas of Central Milton Keynes.

This book, first published in 2007 by Living Archive of Milton Keynes, was commissioned by the Central Milton Keynes Project Board and is illustrated with over 150 full-colour and black-and-white photographs.

Here are the architects, designers, planners, landscape designers, engineers, surveyors, architectural technicians, finance and project managers – the 1970s CMK team who created the original city centre for Milton Keynes. They recall how the centre’s unique infrastructure and buildings came to be designed and built, and explain the thinking behind their work.

They recall their battles with government officials and authorities, with national and local traders, and with each other. They tell their stories of endeavour and frustration, of excitement and panic, and – above all – of their passion.

The key people include Lord Campbell of Eskan, who chaired Milton Keynes Development Corporation; Walter Ismay, MKDC’s first managing director; Fred Lloyd Roche, MKDC General Manager; Derek Walker, the chief architect and planning officer; Frank Henshaw, the chief quantity surveyor; and Harry Legg of the John Lewis partnership.

Glenstal Castle, Co Limerick … the family home of Jock Campbell’s maternal ancestors, the Barrington family (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Most accounts of Lord Campbell’s life recall his family background in the sugar plantations of Guyana. But Jock Campbell’s obituary in The Independent in 1995 described how he was raised in Ireland.

John Middleton Campbell, Baron Campbell of Eskan (1912-1994), was born ‘with a silver sugar spoon in his mouth. He was the chair of Booker-McConnell in what was once British Guiana (1952-1967), he chaired the Commonwealth Sugar Exporters Association (1950-1984), and also chaired the New Statesman and Nation.

Jock Campbell was born on 8 August 1912. His father, Colin Algernon Campbell, was a son of William Middleton Campbell, Governor of the Bank of England (1907-1909). His mother,

Mary Charlotte Gladys Barrington (1889-1981), was born on 13 September 1889 at Glenstal Castle, Co Limerick – now Glenstal Abbey, a Benedictine abbey and school.

Mary Campbell’s father, Jock Campbell’s grandfather, John Beatty Barrington (1859-1926) was a son of Sir Croker Barrington, 4th Baronet, of Glenstal Castle. He was baptised in Saint Stephen’s Church, Dublin, and educated at Charterhouse and Trinity College. Dublin. He was a land agent in Limerick for his father and later his brother, Sir Charles Burton Barrington (1848-1943), and for the Earl of Limerick.

He was a Justice of the Peace for Limerick City and County and for Co Tipperary, High Sheriff of Co Limerick (1912), and a member of Limerick County Council. He died in Dublin in 1926 and was buried in Mount Jerome Cemetery. He left an estate valued at £17,316, today’s equivalent of over €1.2 million.

During World War I, three-year-old Jock Campbell was sent for safety to the Barrington family home at Glenstal Castle, and spent much of the formative years of his childhood in Co Limerick. Later he was educated went to Eton and Oxford.

His family wealth was inherited from his paternal ancestor, John Campbell, a late 18th century Glasgow ship owner and merchant. This John Campbell established the family fortunes in the West Indies through the slave trade.

John Campbell supplied the slave plantations on the coast of Guiana, then a Dutch colony. By the 20th century, the company of Curtis, Campbell and Co was well established in British Guiana.

Jock Campbell, Lord Campbell of Eskan … ‘the prime reason that Milton Keynes has got the quality it’s got’

Jock Campbell often said his ancestors were de facto slave-owners. He abhorred slavery, and the urge to make good the misdeeds of his own family became the catalyst for his own reformist ideals.

He was sent to British Guiana in 1934 to take charge of the family estates. The Campbells owned Las Penitence Wharf on the Demerara River, Georgetown, and the Ogle and Albion estates further east, and he was shocked by the appalling conditions of the workers.

He soon initiated reforms and merged the family company with the giant Booker Brothers, McConnell and Co, where he became chair. Bookers behaved like a state within a state, owning almost all the colony’s sugar plantations and dominating the economic life of Guiana.

Campbell was convinced that every business has a responsibility towards its workers and that profit alone should not be the guiding principle of society.

He once said: ‘I believe that there should be values other than money in a civilised society. I believe that truth, beauty and goodness have a place. Moreover, I believe that if businessmen put money, profit, greed and acquisition among the highest virtues, they cannot be surprised if, for instance, nurses, teachers and ambulance men are inclined to do the same.’

In effect, Campbell became a socialist-capitalist. The sugar industry was transformed from a run-down, unprofitable, inhuman, paternalistic and plantocratic expatriate family concern into a rehabilitated, forward-looking, productive and dynamic enterprise.

Wages were vastly increased, 15,000 new houses were built in 75 housing areas, with clean water and roads and water, medical services were upgraded, malaria was eradicated, community centres were opened, and educational, welfare, sporting and library facilities were expanded. In an era of tremendous growth and change, the industry was revolutionised and sugar production grew from 170,000 tons to 350,000 tons.

Campbell’s key message was quite simple: People are more important than ships, shops and sugar estates. It was a principle that later inspired his vision for the new city at Milton Keynes.

Campbell was made a life peer by Harold Wilson in 1966 and took the title Baron Campbell of Eskan. He was active in the House of Lords as a Labour peer. Speaking in the House of Lords in 1971, he dissociated himself from his ancestors, saying ‘maximising profits cannot and should not be the sole purpose, or even the primary purpose, of business.’

Campbell was instrumental in initiating the Booker Prize for literature in 1969 through his friendship with Ian Fleming, author of the James Bond books. Bookers acquired a 51% share in Glidmore Productions, the company handling the royalties on Fleming’s books and the merchandising rights – although not the film rights. Bookers later acquired the copyrights of other well-known authors, including Agatha Christie, Dennis Wheatley, Georgette Heyer, Robert Bolt and Harold Pinter. In 2002, the prize was renamed the Man Booker Prize.

Campbell’s mother, Mary Charlotte Gladys (Barrington) Campbell. died at Debsborough Cottage, her mother’s former home in Nenagh, Co Tipperary, on 21 July 1981. After a funeral service in Saint John’s Church, Nenagh, she was buried in Mount Jerome Cemetery, Harold’s Cross, Dublin.

Campbell chaired Milton Keynes Development Corporation from 1967. When he stepped down in 1983, he was succeeded by Sir Henry Chilver. Milton Keynes Development Corporation was wound up in 1992, and Campbell died on 26 December 1994.

The large, central park initially called City Park, was renamed Campbell Park in his honour. A memorial stone by the fountain in reads simply Si monumentum requiris, circumspice (‘If you seek a monument, look about you’), referring to the urban landscape created by his team.

In The Story of the original CMK, Derek Walker describes Campbell as ‘a good old Socialist’ and David Hartley describes him as ‘the man who could fix anything’ and ‘a visionary.’

Fred Roche and Derek Walker were two ‘very individualist and very forceful thinkers, David Hartley recalls, and ‘Fred and Jock are the prime reason that Milton Keynes has got the quality it’s got.’

Campbell Park in Milton Keynes … renamed in honour of the man who gave ‘Milton Keynes … the quality it’s got’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

03 January 2023

Praying at Christmas through poems

and with USPG: 3 January 2023

‘Lost in the world’s wood / … under naked boughs / The frost comes to barb your broken vows’ – RS Thomas (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

‘Lost in the world’s wood / … under naked boughs / The frost comes to barb your broken vows’ – RS Thomas (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)Patrick Comerford

Christmas is not a season of 12 days, despite the popular Christmas song. Christmas is a 40-day season that lasts from Christmas Day (25 December) to Candlemas or the Feast of the Presentation (2 February).

Throughout the 40 days of this Christmas Season, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, Reflecting on a seasonal or appropriate poem;

2, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary, ‘Pray with the World Church.’

As we move from celebrating Christmas and the New Year to facing the stark realities of the year ahead, my choice of a Christmas poem this morning [3 January] is ‘Song at the Year’s Turning,’ written in 1955 by the Welsh priest-poet RS Thomas, and the title poem of the collection that brought him to the attention of the wider world beyond his own Wales.

The Revd Ronald Stewart Thomas (1913-2000) is one of most important Welsh poets of the 20th century, alongside Dylan Thomas. This priest poet writes about his own people in a style that can be compared with the harsh and rugged terrain they inhabit.

John Betjeman, in his introduction to Song at the Year’s Turning (1955), the collection of Thomas’s poetry that brought him to the attention of the wider literary world – and that includes this morning’s poem – predicted Thomas would be remembered long after Betjeman was forgotten. Professor M Wynn Thomas said: ‘He was the Alexander Solzhenitsyn of Wales … He was one of the major English language and European poets of the 20th century.’

RS Thomas trained as an ordinand at Saint Michael’s College, Llandaff (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

RS Thomas trained as an ordinand at Saint Michael’s College, Llandaff (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)RS Thomas was born in Cardiff in 1913, and his family moved in 1918 to Holyhead, where his father worked with a ferry boat company operating between Wales and Ireland. He studied classics at the University College of North Wales, Bangor, and studied theology at Saint Michael’s College, Llandaff, before being ordained deacon in the Church in Wales in 1936 and priest in 1937.

Between 1936 and 1978, he would serve in parishes in six different towns, acquiring first-hand knowledge of farming life and becoming familiar with a host of characters and settings for his poetry. As a curate in the mining village of Chirk in Denbighshire (1936-1940), he met his wife, Mildred (Elsi) Eldridge, an English artist. They married in 1940, and for all their married life, until Elsi died in 1991, they lived on a tiny income and lacked the comforts of modern life, largely by his choice.

From 1942 to 1954, he was the Rector of Manafon, near Welshpool in rural Montgomeryshire. There he began to study Welsh, although he later said he learnt Welsh too late in life to write poetry in it. At Manafon he published his first three volumes of poetry, The Stones of the Field, An Acre of Land and The Minister.

In 1954, he became Vicar of Saint Michael’s, Eglwysfach, in Cardiganshire (1954-1967). A year later, he achieved wider recognition as a poet and was introduced to a wider audience with his fourth book, Song at the Year’s Turning: Poems 1942-1945 (1955), a collected edition of his first three volumes, introduced by John Betjeman.

In the 1960s, he worked in a predominantly Welsh-speaking community and he later wrote two prose works in Welsh, Neb (Nobody), an autobiography written in the third person, and Blwyddyn yn Llŷn (A Year in Llŷn).

From 1967 to 1972, Thomas was the Vicar of Saint Hywyn’s, Aberdaron, at the western tip of the Llŷn Peninsula in Gwynedd, with Saint Mary, Bodferin. The Llŷn Peninsula is the point in Wales that is closest to Ireland. Finally, he was Rector of Rhiw with Llanfaelrhys (1972-1978). He retired in Easter 1978, and he and his wife moved to Y Rhiw, a beautiful part of Wales. However, their cottage was unheated and the temperature sometimes dropped below freezing.

In retirement, he became more active in politics and campaigns, and he was a strong advocate of Welsh nationalism, although he never supported Plaid Cymru. He was a keen supporter of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and described himself as a pacifist. But he also supported the fire-bombings of English-owned holiday cottages in rural Wales, arguing: ‘What is one death against the death of the whole Welsh nation?’

His eightieth birthday was marked by the publication of Collected Poems, 1945-1990. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1996, but that year the prize went to Seamus Heaney.

When he died in 2000 at the age of 87, his life and poetry were celebrated in Westminster Abbey with readings from Seamus Heaney, Andrew Motion, Gillian Clarke and John Burnside. His ashes are buried close to the door of Saint John’s Church, Porthmadog, Gwynedd.

Spiritual questioning and cultural scepticism

The beauty of the landscape is ever-present in the poems of RS Thomas, marked by spiritual questioning and cultural scepticism (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The beauty of the landscape is ever-present in the poems of RS Thomas, marked by spiritual questioning and cultural scepticism (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)Bishop Richard Clarke has described him as ‘a rather terrifying Welsh Anglican clergyman who evidently scared the living daylights out of his parishioners but who was also, and unquestionably, one of the greatest poets in the English language over the past century.’

Thomas was not always charitable and was known for being awkward and taciturn, to the point that he was even accused of being ‘formidable, bad-tempered, and apparently humourless.’ Indeed, he admitted himself that there is a ‘lack of love for human beings’ in his poetry.

When he began to write about the Welsh countryside and its people, Thomas was influenced by Edward Thomas, Fiona Macleod, and WB Yeats. Fearing that poetry was becoming a dying art, inaccessible to those who most needed it, ‘he attempted to make spiritually minded poems relevant within, and relevant to, a science-minded, post-industrial world,’ to represent that world both in form and in content even as he rejected its machinations.

His earlier works focus on the personal stories of his parishioners, the farm labourers and working men and their wives, challenging the cosy view of the traditional pastoral poem with harsh and vivid descriptions of rural lives. The beauty of the landscape is ever-present, but it is never a compensation for the low pay or monotonous conditions of farm work.

As his poetry develops, Thomas moves from the first impact of rural life on a young curate to a more introspective examination of his own agonies and difficulties. His later poetry is marked by spiritual questioning and cultural scepticism.

Thomas’s poetry is often harsh and austere, written in plain, sombre language, with a meditative quality. He uses simple words and short nouns, in a spare, ascetic style that reflects his disenchantment with the modern world and the scientific age. His poems are filled with compassion, love, doubt, and irony. Despite the often grim nature of his subject matter, his poems are ultimately life-affirming.

Thomas the priest poet

As a priest, Thomas imbues his poetry with a consistently religious theme, often speaking of the lonely and often barren predicament of the priest, who is as isolated in his parish as Iago Prytherch – an archetypal rural Welshman found in many of his poems – is on the bare hillside.

He believes one of the important functions of poetry is to embody religious truth, and his work expresses a religious conviction uncommon in modern poetry. Archbishop Rowan Williams – also an acclaimed Welsh priest poet – says Thomas, like Soren Kierkegaard, was a ‘great articulator of uneasy faith.’

An early poem, ‘In a Country Church,’ from Song at the Year’s Turning (1955), announces some of the themes that would dominate his later poetry:

To one kneeling down no word came,

Only the wind’s song, saddening the lips

Of the grave saints, rigid in glass;

Or the dry whisper of unseen wings,

Bats not angels, in the high roof.

Was he balked by silence? He kneeled long,

And saw love in a dark crown

Of thorns blazing, and a winter tree

Golden with fruit of a man’s body.

The opening stanza is a powerful image of silence. The only sounds come not from words but from the wind, not from the wings of angels but of bats. While there is no word from God, the poet gropes for a signal of grace and wrests from the silence a vision of a wintry image of love and crucifixion – perhaps a divine response.

Thomas returns to this theme in ‘In Church,’ a poem from his collection Pieta (1966):

Often I try

To analyze the quality

Of its silences. Is this where God hides

From my searching? I have stopped to listen,

After the few people have gone,

To the air recomposing itself

For vigil. It has waited like this

Since the stones grouped themselves about it.

These are the hard ribs

Of a body that our prayers have failed

To animate. Shadows advance

From their corners to take possession

Of places the light held

For an hour. The bats resume

Their business. The uneasiness of the pews

Ceases. There is no other sound

In the darkness but the sound of a man

Breathing, testing his faith

On emptiness, nailing his questions

One by one to an untenanted cross.

In this poem. Thomas confronts the paradox of presence and absence, faith and doubt. DZ Phillips, in RS Thomas: Poet of the Hidden God, reads the last lines as a realisation that the poet-priest ‘has to die to his old questions. It is only by dying to the old questions that wonder can come in at the right place.’

‘… and throw / on its illumined walls the shadow / of someone greater than I can understand?’ – RS Thomas (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

‘… and throw / on its illumined walls the shadow / of someone greater than I can understand?’ – RS Thomas (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)But did he feel lonely, isolated, or even trapped in parish ministry? He writes, in ‘The Empty Church’:

They laid this stone trap

for him, enticing him with candles,

as though he would come like some huge moth

out of the darkness to beat there.

Ah, he had burned himself

before in the human flame

and escaped, leaving the reason

torn. He will not come any more

to our lure. Why, then, do I kneel still

striking my prayers on a stone

heart? Is it in hope one

of them will ignite yet and throw

on its illumined walls the shadow

of someone greater than I can understand?

Thomas has been described as ‘not a poet of the transfiguration, of the resurrection, of human holiness,’ but as ‘a poet of the Cross, the unanswered prayer, the bleak trek through darkness.’

For Tony Brown of the University of Wales, Thomas’s emphasis remains on the cross, trusted and finally understood as ‘the ultimate demonstration of love defeating time and mortality.’ Rowan Williams concludes that ‘God, for Thomas, is both the frustration of every expectation and the only exit from despair. And that God is encountered only in the embrace of finitude.’

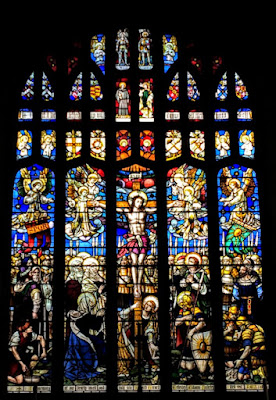

‘Light’s peculiar grace/ In cold splendour robes this tortured place’ – RS Thomas … the Crucifxion window in Saint Mary and Saint Nicholas Church, Beaumaris (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Song at the Year’s Turning by RS Thomas

Shelley dreamed it. Now the dream decays.

The props crumble; the familiar ways

Are stale with tears trodden underfoot.

The heart’s flower withers at the root.

Bury it then, in history’s sterile dust.

The slow years shall tame your tawny lust.

Love deceived him; what is there to say

The mind brought you by a better way

To this despair? Lost in the world’s wood

You cannot stanch the bright menstrual blood.

The earth sickens; under naked boughs

The frost comes to barb your broken vows.

Is there blessing? Light’s peculiar grace

In cold splendour robes this tortured place

For strange marriage. Voices in the wind

Weave a garland where a mortal sinned.

Winter rots you; who is there to blame?

The new grass shall purge you in its flame.

‘under naked boughs / The frost comes to barb your broken vows’ … naked bows at Penmon on the eastern tip of Anglesey (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

USPG Prayer Diary:

The theme in the USPG Prayer Diary this week is ‘Refugee Response in Finland.’ This theme was introduced on Sunday by the Revd Tuomas Mäkipää, Chaplain at Saint Nicholas’ Anglican Church in Helsinki, who tells how a USPG grant is helping to support Ukrainian refugees.

The USPG Prayer Diary invites us to pray today in these words:

Let us pray for the many volunteers working with refugees. May they be sustained in their endeavours and supported when exhaustion sets in.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

‘Light’s peculiar grace / In cold splendour robes this tortured place’ … snow above Thomas Telford’s Suspension Bridge at the Menai Straits linking Anglesey and mainland Wales (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Labels:

Anglesey,

Beaumaris,

Christmas 2022,

Finland,

Llandaff,

Mission,

Penmon,

Poetry,

Prayer,

Ukraine,

USPG,

Wales

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)