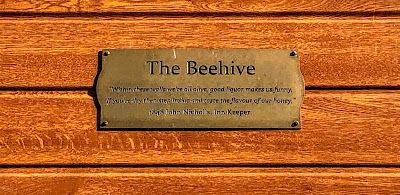

The Beehive at 204 Beacon Street … one of the lost pubs of Lichfield (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

Patrick Comerford

On my regular walks along Beacon Street, between the Hedgehog and the centre of Lichfield, I often wonder about the old pubs that have disappeared from this street in Lichfield.

When I was writing about the lost pubs of Lichfield last year in a blog posting during the pandemic lockdown, I referred to Little George at 60 Beacon Street, on the south side of the corner with Anson Avenue, with the Cathedral Hotel on the north side of the corner.

‘Little George’ closed as a pub in 1956, and its licence was transferred to a new pub, the Windmill on Wheel Lane. It then became a three-bedroom house. I noticed last week that it is still on the market through Bill Tandy Estate Agents of Bore Street, Lichfield, with an asking price that is now put at of £460,000.

A more discreet presence on Beacon Street is the Beehive at No 204. This was one of the short-lived pubs on Beacon Street that had disappeared by the early 20th century.

This too is now a private house, but once again last week I smiled as I read the discreet yet intriguing plaque above the front door that quotes John Nicholls, the landlord in 1848:

Within these walls we’re all alive,

good liquor makes us funny,

if you’re dry then step inside,

and taste the flavour of our honey.

‘If you’re dry then step inside, and taste the flavour of our honey’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

Additional reading:

John Shaw, The Old Pubs of Lichfield (Lichfield: George Lane Publishing, 2001/2007).

Neil Coley, Lichfield Pubs (Stroud: Amberley, 2016).

19 October 2021

Praying in Ordinary Time 2021:

143, Nenagh Friary, Co Tipperary

The Franciscan friary in Nenagh was founded by 1252, perhaps by Theobald Butler of Nenagh Castle and Bishop Donal O’Kennedy of Killaloe (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

The three-day annual clergy conference for priests of the Diocese of Limerick and Killaloe and the Diocese of Tuam, Killala and Achonry continues for a second day today in Adare, Co Limerick.

Before the day begins, I am taking a little time this morning for prayer, reflection and reading. Each morning in the time in the Church Calendar known as Ordinary Time, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, photographs of a church or place of worship;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

My theme for these few weeks is churches in the Franciscan (and Capuchin) tradition. My photographs this morning (19 October 2021) are of the ruins of the Franciscan Friary in Nenagh, Co Tipperary.

The crowning glory of the abbey was its east gable (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The former Franciscan friary or abbey in the centre of Nenagh, Co Tipperary, may have been founded by Theobald Butler, who built Nenagh Castle. But it is also associated with Donal O’Kennedy, Bishop of Killaloe, so that Nenagh friary may have been founded before 1252 with O’Kennedy sponsorship.

The abbey is located in the centre of Nenagh, not far from the castle, the courthouse and the town’s parish churches. The site is on a lane to the south of Pearse Street, the town’s main street, and can be reached from Friar Street, Abbey Street and Martyr’s Road.

Today, the main surviving features of the friary include the walls of a large rectangular church, aligned East/West, which is 43 metres long and 10 metres wide. There is a triple lancet window at the east end and a series of 15 impressive lancet windows along the north wall. The former tower has fallen. Portions of the sacristy survive along the east end of the friary. This sacristy measured 10 x 4 metres.

The Gothic features included the doors and windows. There are sandstone dressings for the piers, jambs, and arches, while limestone was used for the main walls built of random rubble.

The crowning glory of the abbey was its east gable, with three large, elaborate lancet windows, with piers of solid masonry between that are deeply splayed.

There is a small gable light over the east lancet windows, above the level of the roof-slates but below the level of the ridge-piece. This was made for ventilation and for access between the inner and outer roofs to allow for repairs.

A small door in the south wall stood towards the east side that leads to the sacristy. The door has sandstone dressings and is about 5 ft high. There is only one window in the south wall. This tall window in the sanctuary had two lights, and has an eastern jamb that splays widely inwards and a western one that splays only slightly.

The rest of the light for the choir and sanctuary came from the east window and from the 11 tall, narrow, pointed, single-light windows, splaying inwards on the north wall. As well as the 11 windows in the choir, there were four smaller windows in the nave.

The ambulatory across the church divided the nave and choir. The church also had doors in the north and south walls, opposite each other.

The main entrance door is in the middle of the west gable wall. The original west doorway was remodelled around the 15th century with the insertion of a limestone arch and orders.

The bellcote on the apex of the west wall appears to be contemporary with the doorway. Over the west door, there is a vine scroll with a decorated finial and a carved head inserted into it. The figure is wearing a 15th century headdress,and was once thought to be part of an effigy, while the decoration it crowns formed part of an archway. The bell was supplied by Father Eugene Callanan and remains functional to this day.

There are four buttresses on the south wall. Three of these are were not original parts of the abbey and are thought to have been added in the 15th century to support and reinforce the wall. One buttress has started to separate from the wall.

Pattress plates and tie bars run between the north and south walls at the lancet windows are. This supports the walls and stops them from falling outwards, especially the north wall which has a noticeable tilt. Along with the buttresses, the pattress plates and tie bars are keeping the wall from tilting any further.

The friary in Nenagh became the principal Franciscan house in Ireland, and a provincial synod was held at the friary in 1344.

The Annals of Nenagh, which chronicles the deaths of notable local families, was compiled in Nenagh between 1336 and 1528.

At the time of the Reformation, the friary was closed at the suppression of monastic houses throughout Ireland, and the friary was granted to Robert Collum. But it suffered a more serious assault in 1548 when the O’Carrolls burnt Nenagh, including the friary, which was then a conventual house.

The Franciscans continued to maintain a presence in Nenagh until about 1587. No efforts were made to continue that Franciscan presence for almost half a century until the Observant friars arrived in Nenagh in 1632.

The friars were expelled by the Cromwellians but returned after the restoration. A community was still living in Nenagh in the early 18th century, but this had broken up by 1766. Friars continued to work in the area as parish clergy until the last Franciscan in Nenagh, Father Patrick Harty, died in 1817.

The earliest inscribed headstone in the churchyard is for Mrs Frances Minchin, and is dated 1696.The abbey grounds continue to be used as a burial ground.

HG Leask wrote a comprehensive description of the Friary in 1937, when he described the ruin as a simple, long rectangle, without any obvious division into nave and chancel. He recorded the fine windows in the east gable, and 11 windows in the north wall of the choir.

The Franciscan Friary is known popularly in Nenagh as the Abbey, and has given its name to surrounding street such as Friar Street or Abbey Street and local businesses like Friary Iron Works, the Abbey Court Hotel, Abbey Furniture and Abbey Machinery.

The carvings over the west door include a carved head wearing a 15th century headdress (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Luke 12: 35-38 (NRSVA):

[Jesus said:] 35 ‘Be dressed for action and have your lamps lit; 36 be like those who are waiting for their master to return from the wedding banquet, so that they may open the door for him as soon as he comes and knocks. 37 Blessed are those slaves whom the master finds alert when he comes; truly I tell you, he will fasten his belt and have them sit down to eat, and he will come and serve them. 38 If he comes during the middle of the night, or near dawn, and finds them so, blessed are those slaves.’

There was a series of 15 windows along the north wall (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (19 October 2021) invites us to pray:

Let us pray for the Zambia Anglican Council, which represents Anglican churches across Zambia.

Looking into the ruins from the west end (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

Nenagh Castle … the Franciscan friary in Nenagh may have been founded by Theobald Butler of Nenagh Castle; Bishop Michael Flannery planned to incorporate the castle into a new cathedral in Nenagh in the 1860s (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Patrick Comerford

The three-day annual clergy conference for priests of the Diocese of Limerick and Killaloe and the Diocese of Tuam, Killala and Achonry continues for a second day today in Adare, Co Limerick.

Before the day begins, I am taking a little time this morning for prayer, reflection and reading. Each morning in the time in the Church Calendar known as Ordinary Time, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, photographs of a church or place of worship;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

My theme for these few weeks is churches in the Franciscan (and Capuchin) tradition. My photographs this morning (19 October 2021) are of the ruins of the Franciscan Friary in Nenagh, Co Tipperary.

The crowning glory of the abbey was its east gable (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The former Franciscan friary or abbey in the centre of Nenagh, Co Tipperary, may have been founded by Theobald Butler, who built Nenagh Castle. But it is also associated with Donal O’Kennedy, Bishop of Killaloe, so that Nenagh friary may have been founded before 1252 with O’Kennedy sponsorship.

The abbey is located in the centre of Nenagh, not far from the castle, the courthouse and the town’s parish churches. The site is on a lane to the south of Pearse Street, the town’s main street, and can be reached from Friar Street, Abbey Street and Martyr’s Road.

Today, the main surviving features of the friary include the walls of a large rectangular church, aligned East/West, which is 43 metres long and 10 metres wide. There is a triple lancet window at the east end and a series of 15 impressive lancet windows along the north wall. The former tower has fallen. Portions of the sacristy survive along the east end of the friary. This sacristy measured 10 x 4 metres.

The Gothic features included the doors and windows. There are sandstone dressings for the piers, jambs, and arches, while limestone was used for the main walls built of random rubble.

The crowning glory of the abbey was its east gable, with three large, elaborate lancet windows, with piers of solid masonry between that are deeply splayed.

There is a small gable light over the east lancet windows, above the level of the roof-slates but below the level of the ridge-piece. This was made for ventilation and for access between the inner and outer roofs to allow for repairs.

A small door in the south wall stood towards the east side that leads to the sacristy. The door has sandstone dressings and is about 5 ft high. There is only one window in the south wall. This tall window in the sanctuary had two lights, and has an eastern jamb that splays widely inwards and a western one that splays only slightly.

The rest of the light for the choir and sanctuary came from the east window and from the 11 tall, narrow, pointed, single-light windows, splaying inwards on the north wall. As well as the 11 windows in the choir, there were four smaller windows in the nave.

The ambulatory across the church divided the nave and choir. The church also had doors in the north and south walls, opposite each other.

The main entrance door is in the middle of the west gable wall. The original west doorway was remodelled around the 15th century with the insertion of a limestone arch and orders.

The bellcote on the apex of the west wall appears to be contemporary with the doorway. Over the west door, there is a vine scroll with a decorated finial and a carved head inserted into it. The figure is wearing a 15th century headdress,and was once thought to be part of an effigy, while the decoration it crowns formed part of an archway. The bell was supplied by Father Eugene Callanan and remains functional to this day.

There are four buttresses on the south wall. Three of these are were not original parts of the abbey and are thought to have been added in the 15th century to support and reinforce the wall. One buttress has started to separate from the wall.

Pattress plates and tie bars run between the north and south walls at the lancet windows are. This supports the walls and stops them from falling outwards, especially the north wall which has a noticeable tilt. Along with the buttresses, the pattress plates and tie bars are keeping the wall from tilting any further.

The friary in Nenagh became the principal Franciscan house in Ireland, and a provincial synod was held at the friary in 1344.

The Annals of Nenagh, which chronicles the deaths of notable local families, was compiled in Nenagh between 1336 and 1528.

At the time of the Reformation, the friary was closed at the suppression of monastic houses throughout Ireland, and the friary was granted to Robert Collum. But it suffered a more serious assault in 1548 when the O’Carrolls burnt Nenagh, including the friary, which was then a conventual house.

The Franciscans continued to maintain a presence in Nenagh until about 1587. No efforts were made to continue that Franciscan presence for almost half a century until the Observant friars arrived in Nenagh in 1632.

The friars were expelled by the Cromwellians but returned after the restoration. A community was still living in Nenagh in the early 18th century, but this had broken up by 1766. Friars continued to work in the area as parish clergy until the last Franciscan in Nenagh, Father Patrick Harty, died in 1817.

The earliest inscribed headstone in the churchyard is for Mrs Frances Minchin, and is dated 1696.The abbey grounds continue to be used as a burial ground.

HG Leask wrote a comprehensive description of the Friary in 1937, when he described the ruin as a simple, long rectangle, without any obvious division into nave and chancel. He recorded the fine windows in the east gable, and 11 windows in the north wall of the choir.

The Franciscan Friary is known popularly in Nenagh as the Abbey, and has given its name to surrounding street such as Friar Street or Abbey Street and local businesses like Friary Iron Works, the Abbey Court Hotel, Abbey Furniture and Abbey Machinery.

The carvings over the west door include a carved head wearing a 15th century headdress (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Luke 12: 35-38 (NRSVA):

[Jesus said:] 35 ‘Be dressed for action and have your lamps lit; 36 be like those who are waiting for their master to return from the wedding banquet, so that they may open the door for him as soon as he comes and knocks. 37 Blessed are those slaves whom the master finds alert when he comes; truly I tell you, he will fasten his belt and have them sit down to eat, and he will come and serve them. 38 If he comes during the middle of the night, or near dawn, and finds them so, blessed are those slaves.’

There was a series of 15 windows along the north wall (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (19 October 2021) invites us to pray:

Let us pray for the Zambia Anglican Council, which represents Anglican churches across Zambia.

Looking into the ruins from the west end (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

Nenagh Castle … the Franciscan friary in Nenagh may have been founded by Theobald Butler of Nenagh Castle; Bishop Michael Flannery planned to incorporate the castle into a new cathedral in Nenagh in the 1860s (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)