All Saints’ Church is the parish church in the centre of Northampton (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

Patrick Comerford

All Saints’ Church, Northampton, is the parish church in the centre of Northampton. The church was largely built after a fire and was consecrated in 1680 and is a Grade I listed building. Outside London, this is one of the foremost examples of 17th century church architecture in England.

The church was one of the many churches I visited when I was in Northampton last week. From the earliest times, the church on this site has been associated with the life of the borough and of the county.

There has been a church on the site since the Church of All Hallows was built in Northampton by Simon de Senlis or Simon de St Liz, the first Norman Earl of Northampton, who had built Northampton Castle and the town walls in 1080s and 1090s.

Simon de Senlis joined the First Crusade to the Holy Land in 1094, and it is likely that after his return to Northampton, he built the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Northampton ca 1100, and the Church of All Hallows.

Inside All Saints’ Church, Northampton, facing the east end (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

All Hallows’ Church lasted with mediaeval alterations until 20 September 1675, when the collegiate church and much of the old town were destroyed by the Great Fire of Northampton.

The fire began in Saint Mary’s Street, near the castle. The inhabitants fled to the Market Square, but were then forced to evacuate, leaving the buildings to burn, including All Hallows’ Church.

The Parliamentarian leanings of Northampton had resulted in the razing of the castle by King Charles II after his invitation to reclaim the throne in 1660. Despite this, the Earl of Northampton, a friend and confidant of the King, persuaded Charles II to contribute 1,000 tons of timber from the royal forests of Salcey and Rockingham. This gesture, along with the repeal of the ‘chimney tax’ endeared the king to the people of Northamptonshire.

One tenth of the money collected for rebuilding the town was allocated to rebuilding All Hallows’ Church, under the architect Henry Bell from King’s Lynn and Edward Edwards. Bell was living in Northampton at the time, and he set to rebuild the church in a manner similar to Sir Christopher Wren’s designs.

Inside All Saints’ Church, Northampton, facing the west end (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

The central mediaeval tower and the crypt survived the fire. The new church of All Saints was built east of the tower in an almost square plan, with a chancel to the east and a north and south narthex flanking the tower.

The church was built in the style of the churches rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren after the Great Fire of London, and it has in the past been mistakenly attributed to him. The rebuilding of city churches in London was financed through the Rebuilding of London Act 1670. Wren, as Surveyor General of the King’s Works, undertook the operation, and one of his first London churches was Saint Mary-at-Hill.

The interior space of Saint Mary-at-Hill is roughly square in plan, and of a similar size to All Saints’ Church. To the west is the tower, again flanked by a north and south narthex. Wren spanned the square space by a barrel vault in a Greek-cross plan, with a dome at the centre, supported on four columns. If Henry Bell drew his inspiration from any one of Wren’s churches, Saint Mary-at-Hill is the one.

The barrel-vaulting though in All Saints’ is much flatter than in Saint Mary-at-Hill, which has semi-circular vaulting. The dome in All Saints’ is more hemi-spherical, and the columns at Saint Mary-at-Hill are Corinthian with fluting.

The large portico was added to the west end of the church in 1701, in front of the narthex (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

All Saints’ Church is entered through the tower into a barrel vaulted nave. At the centre is a dome, supported on four Ionic columns, which is lit by a lantern above. The barrel vault extends into the aisles from the dome in a Greek-cross form, leaving four flat ceilings in the corners of the church. The church is well lit by plain glass windows in the aisles and originally there was a large east window in the chancel, that is now covered by the reredos.

The plasterwork ceiling is finely decorated, and the barrel vaults are lit by elliptical windows. The rich plasterwork was carried out by Edward Goudge whose work is also to be found in the adjacent Session House.

The rebuilt All Saints’ Church was consecrated and opened in 1680. A large portico was added to the west end in 1701, in front of the narthex, very much in the style of the Inigo Jones portico added to Old Saint Paul’s Cathedral in the 1630s. The portico was added as a memorial to Charles II’s contribution to the rebuilding of the church after the fire, and a statue of him was erected above the portico, dressed in a Roman tunic.

The Mayoral Seat dominates the pews on the south side of the church.

The Memorial or Lady Chapel was the last substantial addition to the church, added in the 1920s in memory of those who lost their lives in the World War I. A recently carved statue of Our Lady of Walsingham adorns the chapel.

The altar and chancel in All Saints’ Church (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

All Saints’ is one of the few parish churches in England to have a Consistory Court. The court is located on the north side of the church, having previously been located in the space now occupied by the coffee shop.

Today, the principal role of Consistory Courts is dispensing faculties dealing with churchyards and church property. They also hear the trial of clergy accused of immoral acts or misconduct (under the Clergy Discipline Act 1892).

The church underwent some restoration in the 1970s under the direction of the then Vicar, the Revd Victor Mallan.

Icons of Saint Peter and Saint Katharine are at the east end before the steps to the Quire. These were painted for the church in 2001 to reflect the parish boundaries, which include the site of Saint Katharine’s Church (demolished) and Saint Peter’s Church.

The narthex, sacristy and lavatories were refurbished in 2008. All Saints’ Bistro, a privately leased coffee shop, operates from its north and south areas, and on the space under the portico. The north end of the coffee shop is named after John Clare, the poet who sat outside this space writing his poems.

The dome is supported on four Ionic columns and is lit by a lantern above (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

At 12 noon on Oak Apple Day (29 May) each year, the choir sings a Latin hymn to Charles II from the roof as the statue is wreathed in oak leaves by the Mayor of Northampton. A similar ceremony takes place on Ascension Day at 7 am.

The choir of All Saints’ Church was formed in the 1100s. There are three groups that make up the choirs: the Boys’ Choir, the Girls’ Choir and the Choral Scholars and Lay Clerks. The boys choir ranges in age from 7 to 15, and the girls from 8 to 18. These choirs sing at five choral services a week, including Sunday Mass and Evensong throughout the week.

The church has three pipe organs and three pianos: The west organ was built by JW Walker in 1982-1983, using pipes and other parts from previous organs. The chancel organ was built by Alfred Monk and rebuilt by Hill, Norman and Beard in 1939 for Saint Andrew’s ‘Scotch’ Church, Bournemouth, and was installed in 2006. The Memorial Chapel organ was built by JW Walker in 1983.

A new ring of 10 bells in the key of E, replacing a heavier ring of eight bells that dated from 1782.

All Saints’ Church is one of the few parish churches in England to have a Consistory Court (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

Previous vicars include Dr Edward Reynolds (1627-1628), who wrote the General Thanksgiving in the Book of Common Prayer and later became Bishop of Norwich (1660-1676). The Revd John Conant was incumbent at the time of the Great Fire in 1675. He later became Archdeacon of Norwich.

John Bales is thought to have lived through three centuries until 1706 when he died at the age of 127. His epitaph is on a tablet at the west end: ‘John Bales, born in this town. He was above 126 years old & had his hearing, sight & memory to ye last. He lived in 3 centuries & was buried ye 14th of Apr 1706.’

The town’s war memorials are behind the church, at the east end. The Cenotaph was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, who also designed the Cenotaphs in Whitehall, Manchester, Glasgow, Delhi, Johannesburg, Toronto, Hong Kong and Auckland, and the War Memorial Gardens at Islandbridge in Dublin.

The Patrons of All Saints are the Bishop of Peterborough and the Royal Foundation of Saint Katharine in Radcliffe.

Father Oliver Coss SSC has been the Rector of All Saints’ Church, with Saint Peter and Saint Katharine since 2016. All Saints’ Church is in the Catholic tradition of the Church of England. The parochial church council passed Resolutions A, B and C in 1993. The parish rejects the ordination of women and receives alternative episcopal oversight from Bishop Norman Banks of Richborough.

The Sunday services are Said Eucharist (Book of Common Prayer) at 8 am and Choral Eucharist (Common Worship) at 10:30 am. The Eucharist is also celebrate at 12:30 on Weekdays. The choirs sing Choral Evensong on Wednesdays and Thursdays. All Saints’ Church is open from 9 am to 5 pm throughout the year, with extended opening on days with choral services.

The Cenotaph behind the east end of the church was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

06 February 2023

6.5 million people are

readers, carers … and

on the move in Ukraine

Within a month of the war beginning in Ukraine, about 6.5 million people had been displaced internally

Patrick Comerford

This blog has reached the monumental landmark of 6.5 million hits. The 6.5 million mark was passed earlier this morning (6 February 2023), and it came as a pleasant delight.

When I began blogging, it took until July 2012 to reach 0.5 million hits. This figure rose to 1 million by September 2013; 1.5 million in June 2014; 2 million in June 2015; 2.5 million in November 2016; 3 million by October 2016; 3.5 million by September 2018; 4 million on 19 November 2019; 4.5 million on 18 June 2020; 5 million on 27 March 2021; 5.5 million on 28 October 2021; and 6 million seven months ago on 1 July 2022.

This means that this blog is getting half a million hits in a seven-month period, somewhere above 71,000 a month, or up to 2,400 a day. In recent days these figures have been exceeded on occasions, with 4,532 hits on Thursday (2 February 2023) and 4,520 hits again on Friday (3 February 2023).

With this latest landmark figure of 6.5 million hits, I found myself asking: what do 6.5 million people look like?

Within a month of the war beginning in Ukraine last February, the UN confirmed that about 6.5 million people had been displaced internally in Ukraine, and by May over 6.5 million people had fled Ukraine.

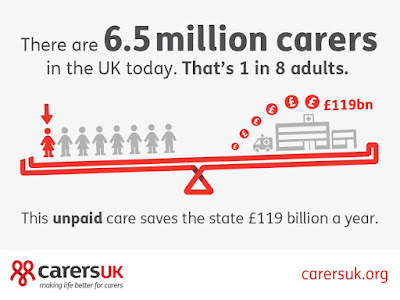

The hospital waiting list in Britain reached 6.5 million last summer, according to the NHS, and things are only getting worse. Figures also show at least 6.5 million people are providing unpaid care in the UK.

About 6.5 million people in the US are living with an intellectual disability, and another 6.5 million Americans are living with Alzheimer's disease.

UN figures confirm that there have been more than 6.5 million Covid-19-related deaths globally since the pandemic began, and 6.5 million people die each year from diseases related to air pollution.

The population of Ireland exceeds 6.5 million: the Republic of Ireland (5 million) and Northern Ireland (1.9 million). Countries with populations of about 6.5 million people include Nicaragua, Kyrgyzstan and El Salvador. Cities with about 6.5 million people include Santiago (Chile), Surat (India), Madrid (Spain) and Suzhou (China).

Glin Castle in Co Limerick was reportedly on the market recently with an asking price of €6.5 million, and Rod Stewart recently paid €6.5 million for a new apartment in n the Lansdowne Place development overlooking the Aviva Stadium.

I have said so often before that this is not a ‘bells-and-whistles’ blog, and I still hope it is never going to be a commercial success. It was never designed to be so.

I decline advertising and commercial sponsorships, I accept no ‘freebies,’ and I endorse no products. Even when I am political, mainly about war and peace, racism, human rights and refugees, I refuse to declare my personal party preferences when it comes to voting.

I continue to resist commercial pressures, I have refused to receive books from publishers and I only review books I have bought myself. Without making too much a point of it, I value my independence so much that I refuse the offer of coffee when I return to a restaurant I mention … as journalists like to be reminded, there is no such thing as a free meal.

The half dozen most popular postings on this blog so far have been:

1, About me (1 May 2007), almost 33,000 hits.

2, The Transfiguration: finding meaning in icons and Orthodox spirituality (7 April 2010), almost 30,000 hits.

3, ‘When all that’s left of me is love, give me away’ … a poem before Kaddish has gone viral (15 January 2020), over 24,000 hits.

4, A visit to Howth Castle and Environs (19 March 2012), over 16,000 hits.

5, Readings in Spirituality: the novelist as a writer in spirituality and theology (26 November 2009), over 16,500 hits.

6, Raising money at the book stall and walking the beaches of Portrane (1 August 2011), about 12,000 hits.

When I think of 6.5 million hits, I think of 6.5 people, and today I am humble of heart rather than having a swollen head.

Figures show at least 6.5 million people are providing unpaid care in the UK

Patrick Comerford

This blog has reached the monumental landmark of 6.5 million hits. The 6.5 million mark was passed earlier this morning (6 February 2023), and it came as a pleasant delight.

When I began blogging, it took until July 2012 to reach 0.5 million hits. This figure rose to 1 million by September 2013; 1.5 million in June 2014; 2 million in June 2015; 2.5 million in November 2016; 3 million by October 2016; 3.5 million by September 2018; 4 million on 19 November 2019; 4.5 million on 18 June 2020; 5 million on 27 March 2021; 5.5 million on 28 October 2021; and 6 million seven months ago on 1 July 2022.

This means that this blog is getting half a million hits in a seven-month period, somewhere above 71,000 a month, or up to 2,400 a day. In recent days these figures have been exceeded on occasions, with 4,532 hits on Thursday (2 February 2023) and 4,520 hits again on Friday (3 February 2023).

With this latest landmark figure of 6.5 million hits, I found myself asking: what do 6.5 million people look like?

Within a month of the war beginning in Ukraine last February, the UN confirmed that about 6.5 million people had been displaced internally in Ukraine, and by May over 6.5 million people had fled Ukraine.

The hospital waiting list in Britain reached 6.5 million last summer, according to the NHS, and things are only getting worse. Figures also show at least 6.5 million people are providing unpaid care in the UK.

About 6.5 million people in the US are living with an intellectual disability, and another 6.5 million Americans are living with Alzheimer's disease.

UN figures confirm that there have been more than 6.5 million Covid-19-related deaths globally since the pandemic began, and 6.5 million people die each year from diseases related to air pollution.

The population of Ireland exceeds 6.5 million: the Republic of Ireland (5 million) and Northern Ireland (1.9 million). Countries with populations of about 6.5 million people include Nicaragua, Kyrgyzstan and El Salvador. Cities with about 6.5 million people include Santiago (Chile), Surat (India), Madrid (Spain) and Suzhou (China).

Glin Castle in Co Limerick was reportedly on the market recently with an asking price of €6.5 million, and Rod Stewart recently paid €6.5 million for a new apartment in n the Lansdowne Place development overlooking the Aviva Stadium.

I have said so often before that this is not a ‘bells-and-whistles’ blog, and I still hope it is never going to be a commercial success. It was never designed to be so.

I decline advertising and commercial sponsorships, I accept no ‘freebies,’ and I endorse no products. Even when I am political, mainly about war and peace, racism, human rights and refugees, I refuse to declare my personal party preferences when it comes to voting.

I continue to resist commercial pressures, I have refused to receive books from publishers and I only review books I have bought myself. Without making too much a point of it, I value my independence so much that I refuse the offer of coffee when I return to a restaurant I mention … as journalists like to be reminded, there is no such thing as a free meal.

The half dozen most popular postings on this blog so far have been:

1, About me (1 May 2007), almost 33,000 hits.

2, The Transfiguration: finding meaning in icons and Orthodox spirituality (7 April 2010), almost 30,000 hits.

3, ‘When all that’s left of me is love, give me away’ … a poem before Kaddish has gone viral (15 January 2020), over 24,000 hits.

4, A visit to Howth Castle and Environs (19 March 2012), over 16,000 hits.

5, Readings in Spirituality: the novelist as a writer in spirituality and theology (26 November 2009), over 16,500 hits.

6, Raising money at the book stall and walking the beaches of Portrane (1 August 2011), about 12,000 hits.

When I think of 6.5 million hits, I think of 6.5 people, and today I am humble of heart rather than having a swollen head.

Figures show at least 6.5 million people are providing unpaid care in the UK

Praying in Ordinary Time

with USPG: 6 February 2023

The cross from the rubble of Urakami Cathedral was returned to Nagasaki in 2019 (Photograph: Randy Sarvis / Wilmington College)

Patrick Comerford

Before today becomes a busy day I am taking some time for prayer and reflection early this morning.

These weeks, between the end of Epiphany and Ash Wednesday, are known as Ordinary Time. We are in a time of preparation for Lent, which in turn is a preparation for Holy Week and Easter.

In these days of Ordinary Time before Ash Wednesday later this month (22 February), I am reflecting in these ways each morning:

1, reflecting on a saint or interesting person in the life of the Church;

2, one of the lectionary readings of the day;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary, ‘Pray with the World Church.’

Christ crucified on the Mushroom Cloud … an icon of Our Lady of Mount Carmel by Kristin McCarthy

The calendar of the Church of England in Common Worship today remembers the Martyrs of Japan (1597) with a commemoration.

Almost 50 years after Francis Xavier had arrived in Japan as its first Christian apostle, the presence of several thousand baptised Christians in Japan became a subject of suspicion to the ruler Hideyoshi. In a period of persecution, 26 men and women, religious and lay, were first mutilated then crucified near Nagasaki in 1597, the most famous of whom was Paul Miki.

After their martyrdom, their blooded clothes were kept and held in reverence by their fellow Christians. The period of persecution continued for another 35 years, many new witness-martyrs being added to their number.

The place of Nagasaki in the history of Christianity in Japan adds additional poignancy to the story of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945.

The Japanese city of Kokura was the initial target for the crew members of the B-29 bomber Bockscar. But low visibility that day forced them to abandon their mission. They were flying low, scanning for an opening in the clouds, when they found a clear patch of sky unexpectedly.

Below them lay the city of Nagasaki and the massive Mitsubishi arms factory. They decided they had found the target for the world’s most powerful weapon, a 4.5-ton plutonium bomb nick-named ‘Fat Man’ – the Hiroshima bomb was known as ‘Little Boy.’

The bomb that day killed tens of thousands of people and wiped out the city in an instant. Just 500 metres from ground zero was Urakami Cathedral, or the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception.

This cathedral had been at the heart of a vibrant Catholic community that dates back to Nagasaki’s early days as a trading port and the arrival of Saint Francis Xavier and other Christian missionaries in the 16th century. For centuries, generations of Christians in Nagasaki had been tortured, banished, and executed and forced to practice their faith in secrecy until the ban on Christianity was lifted in 1873.

The Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception was built between 1895 and 1925. The bomb on 9 August 1945 fell on Nagasaki just 20 years after Urakami Cathedral had been completed. The priest and several parishioners who were inside at the time were destroyed along with much of the church’s memories and history.

The cathedral has since been rebuilt and in recent years a small piece of that history was returned to the cathedral: a cross, mostly forgotten, had been taken from the rubble and Walter Hooke, a former US Marine.

Hooke gave the cross to Wilmington College, a Quaker-run liberal arts college in rural south-west Ohio, where the Peace Resource Centre houses reference materials related to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The centre was set up in 1975 by the late Barbara Reynolds, an American Quaker and anti-nuclear activist who died in 1990.

How did Hooke come across the cross? He had been stationed in Nagasaki after the bombing. Hooke was a devout Catholic and arrived in Nagasaki in October 1945. He developed a friendship with Aijiro Yamaguchi, then the Bishop of Nagasaki. Hooke’s son told the Asahi Shimbun, a leading Japanese newspaper, that the Bishop gave Hooke the cross, perhaps in the hope that it might change Americans’ perceptions of the bomb.

‘One of the things that always really bothered my father was that a Christian country bombed a cathedral that was a centre of Christianity in Asia,’ Christopher Hooke said at his home in Yonkers, New York. ‘There was absolutely no strategic value in the bombing of Nagasaki. I think that was the point.’

Hooke died in 2010 at the age of 97, and the cross remained in Wilmington for decades. But on 6 August 2019, on the 74th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing, Tanya Maus, director of the Peace Resource Centre at Wilmington College, gave the cross to the Archbishop of Nagasaki.

Archbishop Mitsuaki Takami was exposed to radiation in the womb while his mother was pregnant in Nagasaki.

Dr Maus decided to return the cross after she read a report in the Asahi Shimbun that the Nagasaki Peace Association had been trying to locate the cross for 30 years.

Dr Maus contacted Church officials in Nagasaki in April. ‘I started to think about the idea of ‘should it really be here?’ Maybe it needs to be in Nagasaki, where people can sort of explore that history more and the meaning of the cross more.’

‘For me the cross represents human depravity. The utter stripping away of values, in this case Christian values, but it could be any values, that keep human beings from killing each other and destroying each other,’ she was quoted as saying in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. ‘Part of giving it back was letting go of that and making it accessible to people who want to find their own meaning in it.’

‘Atomic bomb victims will die, but the cross will remain as a living witness to what happened in Nagasaki,’ Archbishop Mitsuaki Takami of Nagasaki said when he received from the cross from Dr Maus on Wednesday.

‘The cross is an embodiment of the brutality of war,’ Dr Maus said. ‘The cross is a cry to the US government and governments of other countries that possess nuclear weapons to stop the use of nuclear weapons,’ she said after handing over the cross to Archbishop Takami in Urakami Cathedral.

Dr Maus said the cross will be displayed alongside the head of a wooden sculpture of the Virgin Mary known as the ‘Bombed Mary,’ whose glass eyes were melted by the atomic bomb.

Archbishop Mitsuaki Takami of Nagasaki (centre) receives the cross that survived the atomic bombing of Nagasaki from Tanya Maus (right) of Wilmington College, Ohio, at Urakami Cathedral, with Chitose Fujita, a member of the cathedral congregation (Photograph: Masaru Komiyaji / Asahi Shimbun)

Mark 6: 53-56 (NRSVA):

53 When they had crossed over, they came to land at Gennesaret and moored the boat. 54 When they got out of the boat, people at once recognized him 55 and rushed about that whole region and began to bring the sick on mats to wherever they heard he was. 56 And wherever he went, into villages or cities or farms, they laid the sick in the marketplaces and begged him that they might touch even the fringe of his cloak, and all who touched it were healed.

Saint Francis Xavier among the Jesuit saints … a fresco in the former Jesuit church in the Crescent, Limerick (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

USPG Prayer Diary:

The theme in the USPG Prayer Diary this week is ‘Christianity in Pakistan.’ This theme was introduced yesterday by Nathan Olsen.

The USPG Prayer Diary today invites us to pray in these words:

Let us pray for the bishops of Pakistan. May their faith sustain and encourage one another in difficult times and be an inspiration to their church communities.

Yesterday’s Reflection

Continued Tomorrow

A sermon for Nagasaki Day, 9 August 2020, shared by USPG

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Patrick Comerford

Before today becomes a busy day I am taking some time for prayer and reflection early this morning.

These weeks, between the end of Epiphany and Ash Wednesday, are known as Ordinary Time. We are in a time of preparation for Lent, which in turn is a preparation for Holy Week and Easter.

In these days of Ordinary Time before Ash Wednesday later this month (22 February), I am reflecting in these ways each morning:

1, reflecting on a saint or interesting person in the life of the Church;

2, one of the lectionary readings of the day;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary, ‘Pray with the World Church.’

Christ crucified on the Mushroom Cloud … an icon of Our Lady of Mount Carmel by Kristin McCarthy

The calendar of the Church of England in Common Worship today remembers the Martyrs of Japan (1597) with a commemoration.

Almost 50 years after Francis Xavier had arrived in Japan as its first Christian apostle, the presence of several thousand baptised Christians in Japan became a subject of suspicion to the ruler Hideyoshi. In a period of persecution, 26 men and women, religious and lay, were first mutilated then crucified near Nagasaki in 1597, the most famous of whom was Paul Miki.

After their martyrdom, their blooded clothes were kept and held in reverence by their fellow Christians. The period of persecution continued for another 35 years, many new witness-martyrs being added to their number.

The place of Nagasaki in the history of Christianity in Japan adds additional poignancy to the story of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945.

The Japanese city of Kokura was the initial target for the crew members of the B-29 bomber Bockscar. But low visibility that day forced them to abandon their mission. They were flying low, scanning for an opening in the clouds, when they found a clear patch of sky unexpectedly.

Below them lay the city of Nagasaki and the massive Mitsubishi arms factory. They decided they had found the target for the world’s most powerful weapon, a 4.5-ton plutonium bomb nick-named ‘Fat Man’ – the Hiroshima bomb was known as ‘Little Boy.’

The bomb that day killed tens of thousands of people and wiped out the city in an instant. Just 500 metres from ground zero was Urakami Cathedral, or the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception.

This cathedral had been at the heart of a vibrant Catholic community that dates back to Nagasaki’s early days as a trading port and the arrival of Saint Francis Xavier and other Christian missionaries in the 16th century. For centuries, generations of Christians in Nagasaki had been tortured, banished, and executed and forced to practice their faith in secrecy until the ban on Christianity was lifted in 1873.

The Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception was built between 1895 and 1925. The bomb on 9 August 1945 fell on Nagasaki just 20 years after Urakami Cathedral had been completed. The priest and several parishioners who were inside at the time were destroyed along with much of the church’s memories and history.

The cathedral has since been rebuilt and in recent years a small piece of that history was returned to the cathedral: a cross, mostly forgotten, had been taken from the rubble and Walter Hooke, a former US Marine.

Hooke gave the cross to Wilmington College, a Quaker-run liberal arts college in rural south-west Ohio, where the Peace Resource Centre houses reference materials related to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The centre was set up in 1975 by the late Barbara Reynolds, an American Quaker and anti-nuclear activist who died in 1990.

How did Hooke come across the cross? He had been stationed in Nagasaki after the bombing. Hooke was a devout Catholic and arrived in Nagasaki in October 1945. He developed a friendship with Aijiro Yamaguchi, then the Bishop of Nagasaki. Hooke’s son told the Asahi Shimbun, a leading Japanese newspaper, that the Bishop gave Hooke the cross, perhaps in the hope that it might change Americans’ perceptions of the bomb.

‘One of the things that always really bothered my father was that a Christian country bombed a cathedral that was a centre of Christianity in Asia,’ Christopher Hooke said at his home in Yonkers, New York. ‘There was absolutely no strategic value in the bombing of Nagasaki. I think that was the point.’

Hooke died in 2010 at the age of 97, and the cross remained in Wilmington for decades. But on 6 August 2019, on the 74th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing, Tanya Maus, director of the Peace Resource Centre at Wilmington College, gave the cross to the Archbishop of Nagasaki.

Archbishop Mitsuaki Takami was exposed to radiation in the womb while his mother was pregnant in Nagasaki.

Dr Maus decided to return the cross after she read a report in the Asahi Shimbun that the Nagasaki Peace Association had been trying to locate the cross for 30 years.

Dr Maus contacted Church officials in Nagasaki in April. ‘I started to think about the idea of ‘should it really be here?’ Maybe it needs to be in Nagasaki, where people can sort of explore that history more and the meaning of the cross more.’

‘For me the cross represents human depravity. The utter stripping away of values, in this case Christian values, but it could be any values, that keep human beings from killing each other and destroying each other,’ she was quoted as saying in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. ‘Part of giving it back was letting go of that and making it accessible to people who want to find their own meaning in it.’

‘Atomic bomb victims will die, but the cross will remain as a living witness to what happened in Nagasaki,’ Archbishop Mitsuaki Takami of Nagasaki said when he received from the cross from Dr Maus on Wednesday.

‘The cross is an embodiment of the brutality of war,’ Dr Maus said. ‘The cross is a cry to the US government and governments of other countries that possess nuclear weapons to stop the use of nuclear weapons,’ she said after handing over the cross to Archbishop Takami in Urakami Cathedral.

Dr Maus said the cross will be displayed alongside the head of a wooden sculpture of the Virgin Mary known as the ‘Bombed Mary,’ whose glass eyes were melted by the atomic bomb.

Archbishop Mitsuaki Takami of Nagasaki (centre) receives the cross that survived the atomic bombing of Nagasaki from Tanya Maus (right) of Wilmington College, Ohio, at Urakami Cathedral, with Chitose Fujita, a member of the cathedral congregation (Photograph: Masaru Komiyaji / Asahi Shimbun)

Mark 6: 53-56 (NRSVA):

53 When they had crossed over, they came to land at Gennesaret and moored the boat. 54 When they got out of the boat, people at once recognized him 55 and rushed about that whole region and began to bring the sick on mats to wherever they heard he was. 56 And wherever he went, into villages or cities or farms, they laid the sick in the marketplaces and begged him that they might touch even the fringe of his cloak, and all who touched it were healed.

Saint Francis Xavier among the Jesuit saints … a fresco in the former Jesuit church in the Crescent, Limerick (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

USPG Prayer Diary:

The theme in the USPG Prayer Diary this week is ‘Christianity in Pakistan.’ This theme was introduced yesterday by Nathan Olsen.

The USPG Prayer Diary today invites us to pray in these words:

Let us pray for the bishops of Pakistan. May their faith sustain and encourage one another in difficult times and be an inspiration to their church communities.

Yesterday’s Reflection

Continued Tomorrow

A sermon for Nagasaki Day, 9 August 2020, shared by USPG

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)