‘As Easy as Pie’ … set out our project like you would set out the ingredients and recipe for baking a cake

Patrick Comerford

1, Don’t panic:

Start in time and pace yourself. A good jockey in a race knows how many furlongs there are to the end, and how many fences are left to jump. You would not bake a cake without first setting out your ingredients, and setting out the baking instructions in the recipe.

Work out how long you have to complete your task, and work out the stages you have to pass through by particular days or weeks. If you are still researching your topic with only a week or two to go for submitting your dissertation, or a day or two to go to submitting your essay, then you have not paced your research.

And if the deadline is looming, and you are behind in the race, you start to panic. When we are running and panicking we are most likely to trip and fall.

Preparing the ingredients, understanding the baking instructions, having a recipe in front of you means it all ought to be as “Easy as Pie”

2, Don’t put it off:

You can spend a lot of time, thinking about a topic, mulling it over, or even delaying your reading and writing because the task seems so daunting. Set aside time each day for reading and time each day for writing. They will accumulate over the days and weeks, and it also means your project will seep into the back of your mind, so you can live with it without panicking.

3, Don’t roll it all out:

It is very tempting to repeat everything you have read and learned about a research topic. But just because you have stumbled across it does not make it original, interesting or even exciting. Part of a researcher’s skill is sifting and showing discernment.

4, Don’t hide behind the thinking of others:

Too often it is easy to write an essay as a string of quotations and citations, and then think because they have been placed in a correct order you have made a cogent argument. Not so. I want to know what you think, I want to know whether you agree or not, and why. There is no point in saying something like: “Moltmann is correct when he says …” Tell me why you think he is correct to say so.

5, Don’t rush in:

Don’t set about writing a paper because you find the topic interesting. Read around it for a while before settling on your topic. This is particularly true for a dissertation topic. If you are going to eat, sleep, drink and walk with a topic for 9-12 months, make sure it is one you are happy to live with, not one you wish you could get a quick divorce from.

6, Don’t lose your focus:

Keep your eye on the research title. Too often we are inclined to see words in an essay title, for example, that appeal to us, and then use those words to hang everything we know on one issue on them. Research topics are not a washing line. Focus on the topic in hand, keep your eyes on it, and do not be distracted by extraneous topics.

7, Don’t get fixed on words and length:

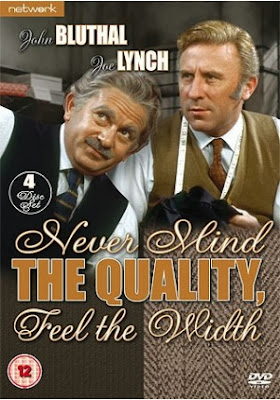

‘Never Mind the Quality, Feel the Width’ … never mind the quantity, pay attention to the quality of your research and its presentation

When it comes to essays, I have sometimes heard student say things like “I have only another 500/400/300/100 to write.” There was a 1960s television sitcom series about an Irish and a Jewish tailor, Never Mind the Quality, feel the Width. I can assure you will get more marks for quality in your essay or dissertation than for the quantity of words. Albert Einstein was able to express a major thought in a simple formula: E = mc2.

Albert Einstein put it simply and succinctly

8, Don’t restrict your reading:

If you do not read, you cannot allow other people’s ideas to reach out to you and inhabit your space. If you search only on the internet or on your Kindle for the books you already know fit your bill, you are not engaging in reading and research – you are engaging in proof texting. Don’t just browse the internet, browse the open shelves in the library, read beyond your comfort zone. Be challenged, be open to being challenged. Otherwise the Church will not be challenged by what you have to say. A limited bibliography is a sign of a closed mind.

9, Don’t repeat the lecture notes:

If you choose a topic that has been covered in your lectures, and you then reference and footnote the online lecture notes, I am going to say: “So what? I know this already. I told you so.”

10, Don’t generalise:

There is a song by Leonard Cohen, Everybody Knows. Don’t tell me “Everybody knows.” Well, if it is, why did you state it? “It is well known …, all Christians believe, … It is right and proper, … it is meek and right so to do …” Why? Give me reasons. Or was your research not completed?

11, Don’t co-opt your reader:

Generalisations can stoop to co-opting your reader. It is only one step to move from saying “Everyone knows” to saying “Every Christian believes.” Remember your essays and dissertations are being written first for the university, and secondly for the general public. If you say something like “Every Christian believes,” I may arch my back and say: “Oh no I don’t …” and quickly find places where I do not accept your other premises.

12, Don’t miss out on basic details:

Facts are not facts unless they are referenced. And references are fictional if they are not factual. If you are presenting statistical analysis, make sure your calculations add up, and are numbered properly. If you quote an author, get the author’s name right, and the title of the book, and the publisher’s name, and the place of publication, and the date of publication. An author may have changed his/her view in a later edition. Use the most up-to-date version of books, especially standard reference books in your field.

13, Don’t show me you don’t care:

Getting basic facts wrong shows me don not care about your topic. You might ask: “Does it really matter?” If you find yourself asking that question, you really don’t care.

14, Don’t forget your language:

It is easy to stoop to folk-language and colloquialism. It may work at home, but it does not work here, and it does not work with the external examiner, or with the general reader. The best way to improve your English is to read. Don’t just read to mine facts and information for your research. Notice how other people write, and which writing styles you find easy to read.

(Revd Canon Professor) Patrick Comerford is Lecturer in Anglicanism, Liturgy and Church History, the Church of Ireland Theological Institute. These notes were prepared for a seminar on research and writing with Year II MTh students on 27 January 2016.

27 January 2016

A note on this evening’s hymns

and the story of ‘Mavourneen’

Jesus rejected in the Synagogue … James Tissot (1836-1902)

Patrick Comerford

I am presiding at the Community Eucharist in the chapel of the Church of Ireland Theological Institute this evening [27 January], and the Revd Dr William Olhausen is the preacher.

We are using the Readings, Collect and Post-Communion Prayer of the Third Sunday after the Epiphany: Nehemiah 8: 1-3, 5-6, 8-10; Psalm 19; I Corinthians 12: 12-31a; and Luke 4: 14-21.

The booklet prepared for this evening includes two illustrations of the Gospel reading.

The cover image of ‘Jesus rejected in the Synagogue’ is a painting by the French artist James Tissot (1836-1902). He was born Jacques Joseph Tissot in Nantes on 15 October 1836 but he Anglicised his name while he was still in his teens. He was a successful painter of Paris society before moving to London in 1871. He became famous as a genre painter of fashionably dressed women shown in various scenes of everyday life. He also painted scenes and characters from the Bible.

Tissot’s mother, Marie Durand, was a devout Catholic who instilled pious devotion in her son at a very young age. In 1856 or 1857, he moved to study in Paris where he stayed with his mother’s friend, the painter Elie Delaunay. There too he got to know the American painter James McNeill Whistler and the French painters Edgar Degas and Édouard Manet.

He took part in the Franco-Prussian War as part of the Paris Commune in the defence of Paris. Perhaps because of these radical political associations, he left Paris in 1871 for London, where he worked as a caricaturist for Vanity Fair and exhibited at the Royal Academy. In London, he lived in Grove End Road in Saint John's Wood, an area then popular with artists, and his work was snatched up by wealthy British industrialists.

Around 1875 or 1876, Tissot met Kathleen Newton, a divorcee who became his companion, his frequent model, his muse and the love of his life. Kathleen ‘Kate’ Newton (1854-1882) was born Kathleen Irene Ashburnham Kelly into an Irish Catholic medical family: her father, Charles Frederick Ashburnham Kelly, was an Irish army officer who was employed by the East India Company in Lahore; her mother, Flora Boyd, was also from Ireland.

Kathleen was raised in Agra and Lahore in India, and when she was 16 she married Isaac Newton, a surgeon with the Indian Civil Service, in January 1870. But even before their marriage was consummated, Newton began divorce proceedings, alleging she had an affair on the passage to India with a Captain Palliser, who never actually seduced her. Her jealous husband sent her back to England. In London she met Tissot, and when she was 23 she posed in 1877 for his painting ‘Mavourneen,’ a title inspired by a term of endearment derived from the Irish mo mhuirnín (“my dear one”), and possibly a reference to ‘Kathleen Mavourneen,’ a popular song and play first staged in London in 1876.

Tissot was fascinated by the conflict of her Irish Catholic background, her divorce and her status as the unmarried mother of two children. She moved into his house in 1876, and they had a son, Cecil George Newton Ashburnham.

Tissot described their life together as ‘domestic bliss,’ and she lived with him until her death in November 1882. When she was diagnosed with tuberculosis, she feared she would be a burden on Tissot and overdosed on Laudanum. When she died, a grieving Tissot sat by her coffin for four days.

After Kathleen’s death, Tissot returned to Paris, and a revival of his Catholic faith in 1885 led him to spend the rest of his life painting Biblical scenes and events, and this evening’s cover painting was completed in 1894. To help his completion of biblical scenes, he travelled to the Middle East in 1886, 1889 and 1896 to study the landscape and the people. His series of 365 illustrations of the life of Christ were shown to critical acclaim and enthusiastic audiences in Paris (1894-1895), London (1896) and New York (1898-1899), before being bought by the Brooklyn Museum in 1900. He spent his last years working on paintings of Old Testament subjects and themes. He died on 8 August 1902.

Christ preaching in the synagogue, Visoki Decani Monastery, Serbia, 14th century

The back cover of this evening’s brochure is illustrated with a 14th century fresco of Christ preaching in the synagogue from the Serbian Orthodox Monastery of Visoki Decani in Kosovo.

The church has a five-nave naos, a three-part iconostasis, and a three-nave parvise. The portals, windows, consoles and capitals are richly decorated. Christ the Judge is shown surrounded by angels in the western part of the Church. Its 20 major cycles of fresco murals represent the largest preserved gallery of Serbian mediaeval art, featuring over 1,000 compositions and several thousand portraits.

The brochure also includes the following:

A note on this evening’s service and hymns:

This evening’s readings, collect and post-communion prayer are those for last Sunday, the Third Sunday after the Epiphany. Two of our hymns this evening are from the new supplemental hymnal, Thanks & Praise.

Processional Hymn: ‘O worship the Lord in the beauty of holiness’ (Church Hymnal, 196) by John SB Maunsell (1811-1875), who was born in Derry, the son of Archdeacon Thomas Bewley Monsell. He served in the dioceses of Derry and Connor for almost 20 years before moving to England, and built or rebuilt three churches. He died when he fell from the roof of Saint Nicholas’s Church, Guildford, while it was being rebuilt. This hymn is based on Psalm 96 and I Chronicles 16. It was written as an Epiphany hymn, but is also popular as a processional hymn.

Gloria: ‘Glory to God’ (Thanks & Praise, 196) is a Peruvian liturgical version of the canticle Gloria in Excelsis Deo, set to a Peruvian traditional chant. It was collected by John Ballantine.

Gradual:‘Rise and hear! The Lord is speaking’ (Church Hymnal, 385) is by Canon Howard Gaunt (1902-1983), a school headmaster and hymn writer who also played county cricket for Warwickshire. The tune ‘Sussex’ by Ralph Vaughan Williams is better known as the setting for ‘Father, hear the prayer we offer’ (Church Hymnal, 645).

Offertory: ‘The feast is ready’ (Church Hymnal, 448) was written by Graham Kendrick for the musical event ‘Make Way for the Cross.’ The music is arranged by Christopher Norton, the composer of the ‘Microjazz’ series, and Alison Cadden, who has been organist of Lisburn Cathedral and Shankill Parish Church, Lurgan.

Communion Hymn: As we receive Holy Communion, we sing ‘Jesus, remember me’ (Church Hymnal, 617), by Jacques Berthier (1923-1994) and the Taizé Community. Berthier, working with Father Robert Giscard and Father Joseph Gelineau, developed the ‘songs of Taizé’ genre. He composed 284 songs and accompaniments for Taizé, including Laudate omnes gentes and Ubi Caritas.

Post Communion Hymn: ‘Go at the call of God’ (Thanks & Praise, 42) is by Canon Rosalind Brown was first published in Being a Priest Today (2002), which she co-wrote with Bishop Christopher Cocksworth. She is a Residentiary Canon and Canon Librarian of Durham Cathedral, and a weekly columnist in the Church Times. The tune Diademata by Sir George Job Elvey (1816-1893), was originally written for ‘Crown him with many crowns’ (Church Hymnal, 263) by Matthew Bridges and Godfrey Thring.

The Collect of the Day:

Almighty God,

whose Son revealed in signs and miracles

the wonder of your saving presence:

Renew your people with your heavenly grace,

and in all our weakness

sustain us by your mighty power;

through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Post-Communion Prayer:

Almighty Father,

your Son our Saviour Jesus Christ is the light of the world.

May your people,

illumined by your word and sacraments,

shine with the radiance of his glory,

that he may be known, worshipped,

and obeyed to the ends of the earth;

for he is alive and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever. Amen.

Patrick Comerford

I am presiding at the Community Eucharist in the chapel of the Church of Ireland Theological Institute this evening [27 January], and the Revd Dr William Olhausen is the preacher.

We are using the Readings, Collect and Post-Communion Prayer of the Third Sunday after the Epiphany: Nehemiah 8: 1-3, 5-6, 8-10; Psalm 19; I Corinthians 12: 12-31a; and Luke 4: 14-21.

The booklet prepared for this evening includes two illustrations of the Gospel reading.

The cover image of ‘Jesus rejected in the Synagogue’ is a painting by the French artist James Tissot (1836-1902). He was born Jacques Joseph Tissot in Nantes on 15 October 1836 but he Anglicised his name while he was still in his teens. He was a successful painter of Paris society before moving to London in 1871. He became famous as a genre painter of fashionably dressed women shown in various scenes of everyday life. He also painted scenes and characters from the Bible.

Tissot’s mother, Marie Durand, was a devout Catholic who instilled pious devotion in her son at a very young age. In 1856 or 1857, he moved to study in Paris where he stayed with his mother’s friend, the painter Elie Delaunay. There too he got to know the American painter James McNeill Whistler and the French painters Edgar Degas and Édouard Manet.

He took part in the Franco-Prussian War as part of the Paris Commune in the defence of Paris. Perhaps because of these radical political associations, he left Paris in 1871 for London, where he worked as a caricaturist for Vanity Fair and exhibited at the Royal Academy. In London, he lived in Grove End Road in Saint John's Wood, an area then popular with artists, and his work was snatched up by wealthy British industrialists.

Around 1875 or 1876, Tissot met Kathleen Newton, a divorcee who became his companion, his frequent model, his muse and the love of his life. Kathleen ‘Kate’ Newton (1854-1882) was born Kathleen Irene Ashburnham Kelly into an Irish Catholic medical family: her father, Charles Frederick Ashburnham Kelly, was an Irish army officer who was employed by the East India Company in Lahore; her mother, Flora Boyd, was also from Ireland.

Kathleen was raised in Agra and Lahore in India, and when she was 16 she married Isaac Newton, a surgeon with the Indian Civil Service, in January 1870. But even before their marriage was consummated, Newton began divorce proceedings, alleging she had an affair on the passage to India with a Captain Palliser, who never actually seduced her. Her jealous husband sent her back to England. In London she met Tissot, and when she was 23 she posed in 1877 for his painting ‘Mavourneen,’ a title inspired by a term of endearment derived from the Irish mo mhuirnín (“my dear one”), and possibly a reference to ‘Kathleen Mavourneen,’ a popular song and play first staged in London in 1876.

Tissot was fascinated by the conflict of her Irish Catholic background, her divorce and her status as the unmarried mother of two children. She moved into his house in 1876, and they had a son, Cecil George Newton Ashburnham.

Tissot described their life together as ‘domestic bliss,’ and she lived with him until her death in November 1882. When she was diagnosed with tuberculosis, she feared she would be a burden on Tissot and overdosed on Laudanum. When she died, a grieving Tissot sat by her coffin for four days.

After Kathleen’s death, Tissot returned to Paris, and a revival of his Catholic faith in 1885 led him to spend the rest of his life painting Biblical scenes and events, and this evening’s cover painting was completed in 1894. To help his completion of biblical scenes, he travelled to the Middle East in 1886, 1889 and 1896 to study the landscape and the people. His series of 365 illustrations of the life of Christ were shown to critical acclaim and enthusiastic audiences in Paris (1894-1895), London (1896) and New York (1898-1899), before being bought by the Brooklyn Museum in 1900. He spent his last years working on paintings of Old Testament subjects and themes. He died on 8 August 1902.

Christ preaching in the synagogue, Visoki Decani Monastery, Serbia, 14th century

The back cover of this evening’s brochure is illustrated with a 14th century fresco of Christ preaching in the synagogue from the Serbian Orthodox Monastery of Visoki Decani in Kosovo.

The church has a five-nave naos, a three-part iconostasis, and a three-nave parvise. The portals, windows, consoles and capitals are richly decorated. Christ the Judge is shown surrounded by angels in the western part of the Church. Its 20 major cycles of fresco murals represent the largest preserved gallery of Serbian mediaeval art, featuring over 1,000 compositions and several thousand portraits.

The brochure also includes the following:

A note on this evening’s service and hymns:

This evening’s readings, collect and post-communion prayer are those for last Sunday, the Third Sunday after the Epiphany. Two of our hymns this evening are from the new supplemental hymnal, Thanks & Praise.

Processional Hymn: ‘O worship the Lord in the beauty of holiness’ (Church Hymnal, 196) by John SB Maunsell (1811-1875), who was born in Derry, the son of Archdeacon Thomas Bewley Monsell. He served in the dioceses of Derry and Connor for almost 20 years before moving to England, and built or rebuilt three churches. He died when he fell from the roof of Saint Nicholas’s Church, Guildford, while it was being rebuilt. This hymn is based on Psalm 96 and I Chronicles 16. It was written as an Epiphany hymn, but is also popular as a processional hymn.

Gloria: ‘Glory to God’ (Thanks & Praise, 196) is a Peruvian liturgical version of the canticle Gloria in Excelsis Deo, set to a Peruvian traditional chant. It was collected by John Ballantine.

Gradual:‘Rise and hear! The Lord is speaking’ (Church Hymnal, 385) is by Canon Howard Gaunt (1902-1983), a school headmaster and hymn writer who also played county cricket for Warwickshire. The tune ‘Sussex’ by Ralph Vaughan Williams is better known as the setting for ‘Father, hear the prayer we offer’ (Church Hymnal, 645).

Offertory: ‘The feast is ready’ (Church Hymnal, 448) was written by Graham Kendrick for the musical event ‘Make Way for the Cross.’ The music is arranged by Christopher Norton, the composer of the ‘Microjazz’ series, and Alison Cadden, who has been organist of Lisburn Cathedral and Shankill Parish Church, Lurgan.

Communion Hymn: As we receive Holy Communion, we sing ‘Jesus, remember me’ (Church Hymnal, 617), by Jacques Berthier (1923-1994) and the Taizé Community. Berthier, working with Father Robert Giscard and Father Joseph Gelineau, developed the ‘songs of Taizé’ genre. He composed 284 songs and accompaniments for Taizé, including Laudate omnes gentes and Ubi Caritas.

Post Communion Hymn: ‘Go at the call of God’ (Thanks & Praise, 42) is by Canon Rosalind Brown was first published in Being a Priest Today (2002), which she co-wrote with Bishop Christopher Cocksworth. She is a Residentiary Canon and Canon Librarian of Durham Cathedral, and a weekly columnist in the Church Times. The tune Diademata by Sir George Job Elvey (1816-1893), was originally written for ‘Crown him with many crowns’ (Church Hymnal, 263) by Matthew Bridges and Godfrey Thring.

The Collect of the Day:

Almighty God,

whose Son revealed in signs and miracles

the wonder of your saving presence:

Renew your people with your heavenly grace,

and in all our weakness

sustain us by your mighty power;

through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Post-Communion Prayer:

Almighty Father,

your Son our Saviour Jesus Christ is the light of the world.

May your people,

illumined by your word and sacraments,

shine with the radiance of his glory,

that he may be known, worshipped,

and obeyed to the ends of the earth;

for he is alive and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever. Amen.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)