The tiny Dingle Record Shop, on Green Street, is probably the most musical 10 square feet (3 sq m) in Ireland (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

When my parents realised that a young age I was thinking of working as a journalism, they had very different, opposing views of my career choice.

My father never accepted my choice: even when I had become Foreign Desk Editor of The Irish Times, with a high national profile and an international reputation, he continued to ask me when I was going to get a ‘real job.’

It was not as though journalism is not in the family: my foster father, George Kerr, was a journalist in the Irish Press, and Maire Comerford worked there too; I have one cousin who worked with the Irish Independent and two who have also worked with The Irish Times. Yet he continued to see me as working in the ‘arty farty world,’ and to urge me to return to the career of a chartered surveyor I had once trained for.

My mother, for her part, immediately encouraged me to start the Guardian – or the Manchester Guardian as she continued to refer it – as the standard for good journalism, and told me I could look to being published in National Geographic magazine as the measure of success in journalism.

I have remained a daily reader of the Guardian ever since. But, while I worked closely with the Guardian and Guardian journalists, and, I never wrote for it … and I never thought of writing for National Geographic.

But, a sumptuously illustrated, colourful new book published by the National Geographic in recent days arrived in the post from Boston early this week, and it includes one of my photographs, taken in Dingle, Co Kerry, almost two years ago.

As the Covid-19 restrictions were being lifted in Ireland that summer, I spent six or seven days on an early summer road trip from Askeaton, Co Limerick, to Co Kerry and west Cork, visiting Dingle, the Blasket Islands, Cape Clear Island, Baltimore, Skibbereen, Rosscarbery, Glengarriff, Garinish Island, Castletownbere, Gougane Barra and Millstreet.

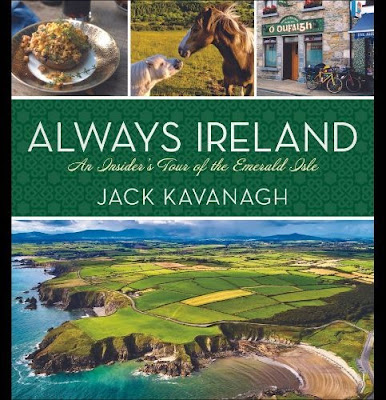

Jack Kavanagh’s new book, Always Ireland, An Insider's Tour of the Emerald Isle, is designed for American readers who want a memorable guide for planning road trips in Ireland or a memorable gift to being home.

This travel guide covers every county of Ireland, visiting Ireland’s best-loved tourist must-sees, from the literary pubs of Dublin to the Cliffs of Moher. The book is divided into the five newly reimagined regions of Irish tourism: the Ancient East; Munster and the South; the Wild Atlantic Way; Ulster and Northern Ireland; and Offshore Ireland.

Visitors are invited to find coastal cliffs and centuries-old castles, art galleries and libraries, distilleries and pubs (especially the pubs of Kilkenny and Killarney), the Wexford Festival – and hurling, the ‘Heroic Game of Ancient Myths.’ There are more than 300 glorious National Geographic images, illustrating recommended itineraries, practical tips and insightful histories, with advice on where to stay, what to eat, and what to do, and recipes introducing the tastes of Ireland, from the ‘Ulster Fry’, soda bread and Irish stew to Guinness and Oysters and Irish coffee and its origins in Foynes, Co Limerick.

Jack Kavanagh began his career in journalism at the Irish Press. Here he introduces the Irish Diaspora around the world, alongside the Poet President Michael D Higgins; historian Diarmaid Ferriter; harp maker Kevin Harrington; singer-songwriter Christy Moore; wild animal conservationist David O’Connor; the writers John Banville, Frank McCourt and Roddy Doyle; and the film maker, Maire Comerford’s nephew, the film maker Joe Comerford, who wrote and directed Reefer and the Model (1988).

There is an interesting archival photograph of James Joyce in Paris with Sylvia Beach, the first publisher of Ulysses.

My photograph on page 137 is of the tiny Dingle Record Shop on Green Street, described in the caption as ‘probably the most musical 10 square feet (3 sq m) in Ireland.’ I photographed the shop when I was in Dingle on 13 June 2021, during that early summer road trip almost two years ago.

The other photographs in this lavish book are places I have visited on that and so many other similar road trips. There is no Bunclody, Millstreet or Askeaton and a mere passing reference to Cappoquin, and the common mistake is repeated of referring to King John’s Castle in Limerick as ‘King John’s Castle’. But Jack Kavanagh is obviously proud of Glendalough in his native Co Wicklow.

Many of the places – from the library in Trinity College Dublin to the beaches of Achill Island – are familiar to most Irish people. But this book is aimed at the American market in particular. No Irish person I know speaks of ‘Éire’, the ‘Enchanting Emerald Isle’ or ‘Celtic Coffee.’ But this is a book by an insider and not for insiders.

If tourists do not bring this book with them at the beginning of their visits, they would be recommended to collect it at the airport on their way home, a thoughtful present or a beautiful reminder of their holiday and road trips.

• Jack Kavanagh, Always Ireland, An Insider's Tour of the Emerald Isle (Washington DC: National Geographic, 2023), 336 pp, hb, ISBN 978-1-4262-2216-0, $35 in US.

07 March 2023

A journey through Lent 2023

with Samuel Johnson (14)

‘What we know amiss in ourselves let us make haste to amend’ … Lucy Porter (1715-1786), step-daughter of Samuel Johnson

Patrick Comerford

During Lent this year, I am taking time each morning to reflect on words from Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), the Lichfield-born lexicographer and writer who compiled the first authoritative English-language dictionary.

Johnson’s stepdaughter, Lucy Porter (1715-1786), was the daughter of Henry Porter, a Birmingham mercer and wool merchant, and his wife Elizabeth who, when she was widowed, married Samuel Johnson. Johnson was just six years older than his new stepdaughter, and their friendship grew increasingly warm as the years passed. She continued to live in Lichfield after her mother moved to London, living with Johnson’s mother Sarah, and helping her to run the bookshop. When her brother died, Lucy inherited £10,000 and built herself a large house on Tamworth Street, Lichfield, that was demolished in the 1920s.

Her friend, Canon John Pearson, inherited a fortune from Lucy Porter, including her house and a number of valuable relics from Dr Johnson, including the manuscript of his Dictionary – later put in the loft in Lichfield, where it was eaten by rats; the bust of Dr Johnston taken after his death – it was displayed on a shelf over a door but fell and broke when the door slammed; and his walking stick – lost when the Pearson family home burned down accidentally ca 1917. However, his writing desk, some of his letters and a signed copy of his Dictionary survived.

Dr Johnson wrote to Lucy Porter in Lichfield on 23 February 1784:

My dearest Love … Death, my dear, is very dreadful, let us think nothing worth our care but how to prepare for it: what we know amiss in ourselves let us make haste to amend, and put our trust in the mercy of God, and the intercession of our Saviour. I am, dear Madam, your most humble servant.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

Patrick Comerford

During Lent this year, I am taking time each morning to reflect on words from Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), the Lichfield-born lexicographer and writer who compiled the first authoritative English-language dictionary.

Johnson’s stepdaughter, Lucy Porter (1715-1786), was the daughter of Henry Porter, a Birmingham mercer and wool merchant, and his wife Elizabeth who, when she was widowed, married Samuel Johnson. Johnson was just six years older than his new stepdaughter, and their friendship grew increasingly warm as the years passed. She continued to live in Lichfield after her mother moved to London, living with Johnson’s mother Sarah, and helping her to run the bookshop. When her brother died, Lucy inherited £10,000 and built herself a large house on Tamworth Street, Lichfield, that was demolished in the 1920s.

Her friend, Canon John Pearson, inherited a fortune from Lucy Porter, including her house and a number of valuable relics from Dr Johnson, including the manuscript of his Dictionary – later put in the loft in Lichfield, where it was eaten by rats; the bust of Dr Johnston taken after his death – it was displayed on a shelf over a door but fell and broke when the door slammed; and his walking stick – lost when the Pearson family home burned down accidentally ca 1917. However, his writing desk, some of his letters and a signed copy of his Dictionary survived.

Dr Johnson wrote to Lucy Porter in Lichfield on 23 February 1784:

My dearest Love … Death, my dear, is very dreadful, let us think nothing worth our care but how to prepare for it: what we know amiss in ourselves let us make haste to amend, and put our trust in the mercy of God, and the intercession of our Saviour. I am, dear Madam, your most humble servant.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)