‘Father Daly’s Chapel’ and the former Mercy Convent in Galway … but who was this ‘turbulent priest’? (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Patrick Comerford

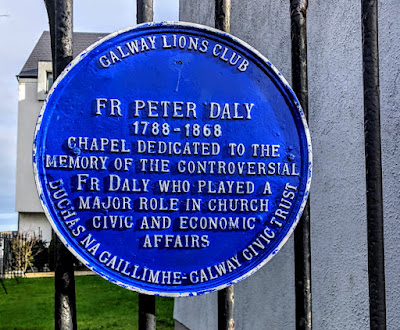

Father Peter Daly is commemorated in Galway on a plaque on the railings of the former Mercy Convent in Newtownsmith, on a prominent site overlooking the River Corrib and across the river from Galway Cathedral.

The plaque describes him as ‘controversial’ and yet says he ‘played a major role in church civic and economic affairs’ in Galway in the 19th century. Still standing beside the railings is the gothic façade of the church once known as ‘Father Daly’s Chapel,’ dating from the 1840s. The façade has been well maintained and has well-preserved stained glass, high-quality limestone masonry and carving on the window openings that make this an interesting site for artistic and architectural reasons.

Father Peter Daly (1788-1868) was the principle mover and shaker behind Galway’s drive to embrace modernity in the 1850s in the immediate aftermath of the Great Famine. But he has been described too as a ‘turbulent priest’, and ‘the dominant public figure in Galway during the 1850s.’ It was said by his opponents that he was ‘a stubborn, abrasive, guileful and egotistical populist.’ So, who was this turbulent priest?

Peter Daly was born near Galway City, but it is difficult to find details about his family background. He was educated at Maynooth and was ordained priest in 1815.

After two short curacies, he was appointed Parish Priest of Saint Nicholas North in Galway City in 1818. There he built a new parish church and he organised several public meetings in 1822-1823 challenging the sectarian politics inflamed by the rise of the ‘new reformation’ among vigorous Evangelical Protestants.

Late in 1823, he was elected to the chapter of the Catholic Wardenship of Galway, which was an ‘exempt jurisdiction,’ autonomous from the Diocese of Tuam. A year later, in 1824 he became the leader of local campaigns against of the proselytising efforts of the London Hibernian Society in Co Galway.

In 1825, Daly also became the Parish Priest of Moycullen. He set up a college house to accommodate the secular clergy of the town, and sought to improve their income and interests against the rival claims by the monastic orders in Galway.

In June 1828, he stood for election as Warden of Galway against Edmund ffrench (1775-1852), then Warden of Galway (1812-1831) and Bishop of Kilmacduagh and Kilfenora, who was a Dominican friar. ffrench was a son of the Church of Ireland Warden of Galway, while his sister was the grandmother of Charles French Blake-Forster (1847-1874) of Forster House, Galway, and author of The Irish Chieftains, introducing yet another link with the Comerford family.

However, Daly failed to receive more than a third of the clerical vote. Archbishop Oliver Kelly of Tuam complained in 1829 of Daly’s scheming against the Warden of Galway and the monastic clergy.

The Wardenship of Galway was abolished in 1831, and George Browne became the first bishop of a new Diocese of Galway. By then, Daly had acquired Blackrock House in Salthill, and he took over the duties of the mensal parish of Rahoon in 1832 on behalf of Browne. By then, Daly had become a local celebrity, and he was visited at his home in Galway by the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, the Earl Mulgrave, in 1835.

When Browne moved to Elphin in 1844, Daly hoped to become Bishop of Galway. But he was opposed strongly by his clerical colleagues and Browne was succeeded by Laurence O’Donnell. Daly soon became involved in high profile disputes with O’Donnell.

O’Donnell, complained to Rome that Daly was ‘totally deficient’ in the two ingredients essential for good character – ‘truth and honesty.’ He described Daly as ‘contumacious’ or wilfully disobedient. Although Daly avoided censure in Rome, relations with his bishop and his colleagues continued to deteriorate.

The plaque commemorating Father Peter Daly at the site of his house and the former Mercy Convent (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Daly founded of a convent of the Sisters of Charity in Galway in 1836, and later persuaded Mother Catherine McAuley of the Sisters of Mercy to take over their work in 1840. He brought the Sisters of Mercy to Saint Vincent’s Convent in Newtownsmith in 1842, built a house and church beside the convent for his own use, and eventually gave both buildings to the nuns.

Newtownsmith was developed as a new area outside Galway’s town walls in the late 18th and early 19th century by the Governors of the Erasmus Smith estate, giving Newtownsmith its name. The county courthouse was built there in 1812-1815 and the town courthouse in 1824. Galway’s second bridge was completed in 1819, connecting the courthouses with the new county and town gaols on Nun’s Island.

A schools superintendent who inspected the Mercy school in May 1845 reported there were 201 girls on the rolls, with an average attendance of 180 in the previous six months. During the Famine, the Mercy Sisters announced in December 1846 that they would provide a ‘daily dinner’ for 100 pupils in the school.

Daly’s house had an elegant façade with carved stone dripstones over all the windows and metal bars on the ground floor windows. The Convent of Mercy stood partly on the site of a Franciscan foundation established by William Liath de Burgo on Saint Stephen’s Island in 1296. A significant collection of old stone carvings, doorways, arches, marriage stones, windows, an archway and a stone urn were built into the wall of the house. Daly may have used mediaeval monuments from the Franciscan site to decorate his house, but they are now missing from the Newtownsmith area.

During the Great Famine, Daly was engaged in relief work, feeding thousands of people. He was co-opted to the board of the town commissioners in Galway in 1847, and became chair in 1848. He gave evidence to the House of Commons committee on the poor laws, and became involved in the Galway gas company, the city harbour board, bringing the railway and the transatlantic packet to Galway, and in the steam navigation of Lough Corrib.

As chair of the town commissioners, Daly was responsible in 1854 for erecting or re-erecting the so-called ‘Lynch Window’ in Galway where James Lynch Fitzstephen, Mayor of Galway in 1493, was said to have condemned and executed his own guilty son, Walter. Daly wrote a new inscription for the gate, but the myth of the ‘Lynch Window’ has since been debunked by the historian James Mitchell. Another historian, Professor TP O’Neill, has described the popular tourist attraction as a ‘monument to [a] non-event.’

Daly led a delegation from Galway to the Prime Minister, the Earl of Derby, in 1858, to seek funds to build a new harbour in Galway. That year, Bishop John MacEvilly of Galway took a case against Daly in Rome, accusing him of financial malpractice, harsh estate management, and of being too absorbed with politics.

MacEvilly also complained to the Vatican that Daly had treated the Sisters of Mercy in Galway ‘most barbarously,’ that he had registered ‘a large amount of ecclesiastical property’ in his own name, and that he was ‘the greatest tyrant in regard to the poor connected with him, either as parish priest or landlord.’

The Galway Vindicator said Daly was ‘the richest ecclesiastic in Ireland.’ Daly sued the Galway Vindicator for libel more than once, then bought the rival Galway Mercury in 1860, installed his brother as editor and changed its name to the Galway Press. Daly was also caricatured in a Punch magazine cartoon in 1861 attempting to bribe the prime minister, Lord Palmerston.

MacEvilly suspended Daly from office in 1862, accusing him of repeated public displays of temper, insulting and bad language, neglecting his pastoral duties, and fomenting discord between the Christian traditions in Galway. MacEvilly also said Daly had treated the Sisters of Mercy ‘most barbarously,’ that he had used the nuns’ money to buy Blackrock House in Salthill, and that he had built a chapel beside their convent at Newtownsmith that was ‘too large, very cold in winter,’ and that he had declared their chapel a public church.

Daly refused to accept his suspension, accused the bishop of being ‘tyrannical’ and appealed directly to Rome and to the Archbishop John McHale of Tuam, who reinstated Daly over MacEvilly’s head.

The conflict with MacEvilly surfaced once again when Daly refused to acknowledge the bishop’s pastoral letter condemning the Galway Model School. Daly was suspended a second time and was criticised for attending trade union meetings, his role as president of the Mechanics’ Institute, and for going to balls.

Even when his suspension was lifted on Christmas Eve 1864, Daly continued to defy MacEvilly. The protracted dispute came to an end only with Daly’s death on 30 September 1868. He is buried in Bushy Park.

For decades, Father Peter Daly had been a leading public figure in Galway and his admirers remained loyal. But he also accumulated considerable personal wealth and property, most of which he bequeathed to his relatives.

The architectural remains of ‘Father Daly’s Chapel’ still standing in Galway today include the triple-gabled west elevation of nave and side aisles, with a three-stage crenellated bell tower at the north end. The original structure behind the façade replaced by a newer building. The pointed arch-headed window openings have tooled chamfered limestone sills, roll chamfered surrounds and hood-mouldings. A four-light cinquefoil-headed window at the former nave has geometric tracery and lead-lined stained glass.

There are pointed arch louvered openings in the upper stages of bell tower, and I understand the ceiling inside has plaster bosses and cornices, with ribs supported on colonettes over corbels.

The architectural remains of ‘Father Daly’s Chapel’ still standing in Galway today (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Additional reading:

James Mitchell, ‘Fr Peter Daly (c.1788–1868)’, Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society, Volume 39, pp 27-114.

Desmond McCabe, ‘Peter Daly,’ Dictionary of Irish Biography.

21 February 2022

Praying with the saints in Ordinary Time: 21 February 2022

Saint Teresa’s Church, Clarendon Street … one of two Carmelite churches in inner-city Dublin (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

Before this day begins, I am taking some time early this morning for prayer, reflection and reading.

The Church Calendar is now in Ordinary Time until Ash Wednesday next week (2 March 2022). During this month in Ordinary Time, I hope to continue this Prayer Diary on my blog each morning, reflecting in these ways:

1, Short reflections drawing on the writings of a great saint or spiritual writer;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

At present, I am exploring the writings of the great Carmelite mystic, Saint Teresa of Avila (1515-1582), so my quotations over these few days are from her writings:

‘The important thing is not to think much, but to love much.’

Mark 9: 14-29 (NRSVA):

14 When they came to the disciples, they saw a great crowd around them, and some scribes arguing with them. 15 When the whole crowd saw him, they were immediately overcome with awe, and they ran forward to greet him. 16 He asked them, ‘What are you arguing about with them?’ 17 Someone from the crowd answered him, ‘Teacher, I brought you my son; he has a spirit that makes him unable to speak; 18 and whenever it seizes him, it dashes him down; and he foams and grinds his teeth and becomes rigid; and I asked your disciples to cast it out, but they could not do so.’ 19 He answered them, ‘You faithless generation, how much longer must I be among you? How much longer must I put up with you? Bring him to me.’ 20 And they brought the boy to him. When the spirit saw him, immediately it threw the boy into convulsions, and he fell on the ground and rolled about, foaming at the mouth. 21 Jesus asked the father, ‘How long has this been happening to him?’ And he said, ‘From childhood. 22 It has often cast him into the fire and into the water, to destroy him; but if you are able to do anything, have pity on us and help us.’ 23 Jesus said to him, ‘If you are able!—All things can be done for the one who believes.’ 24 Immediately the father of the child cried out, ‘I believe; help my unbelief!’ 25 When Jesus saw that a crowd came running together, he rebuked the unclean spirit, saying to it, ‘You spirit that keep this boy from speaking and hearing, I command you, come out of him, and never enter him again!’ 26 After crying out and convulsing him terribly, it came out, and the boy was like a corpse, so that most of them said, ‘He is dead.’ 27 But Jesus took him by the hand and lifted him up, and he was able to stand. 28 When he had entered the house, his disciples asked him privately, ‘Why could we not cast it out?’ 29 He said to them, ‘This kind can come out only through prayer.’

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (21 February 2022) invites us to pray:

Let us pray for all those who are working to achieve social justice. May we all try to be just and merciful in our everyday life.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Patrick Comerford

Before this day begins, I am taking some time early this morning for prayer, reflection and reading.

The Church Calendar is now in Ordinary Time until Ash Wednesday next week (2 March 2022). During this month in Ordinary Time, I hope to continue this Prayer Diary on my blog each morning, reflecting in these ways:

1, Short reflections drawing on the writings of a great saint or spiritual writer;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

At present, I am exploring the writings of the great Carmelite mystic, Saint Teresa of Avila (1515-1582), so my quotations over these few days are from her writings:

‘The important thing is not to think much, but to love much.’

Mark 9: 14-29 (NRSVA):

14 When they came to the disciples, they saw a great crowd around them, and some scribes arguing with them. 15 When the whole crowd saw him, they were immediately overcome with awe, and they ran forward to greet him. 16 He asked them, ‘What are you arguing about with them?’ 17 Someone from the crowd answered him, ‘Teacher, I brought you my son; he has a spirit that makes him unable to speak; 18 and whenever it seizes him, it dashes him down; and he foams and grinds his teeth and becomes rigid; and I asked your disciples to cast it out, but they could not do so.’ 19 He answered them, ‘You faithless generation, how much longer must I be among you? How much longer must I put up with you? Bring him to me.’ 20 And they brought the boy to him. When the spirit saw him, immediately it threw the boy into convulsions, and he fell on the ground and rolled about, foaming at the mouth. 21 Jesus asked the father, ‘How long has this been happening to him?’ And he said, ‘From childhood. 22 It has often cast him into the fire and into the water, to destroy him; but if you are able to do anything, have pity on us and help us.’ 23 Jesus said to him, ‘If you are able!—All things can be done for the one who believes.’ 24 Immediately the father of the child cried out, ‘I believe; help my unbelief!’ 25 When Jesus saw that a crowd came running together, he rebuked the unclean spirit, saying to it, ‘You spirit that keep this boy from speaking and hearing, I command you, come out of him, and never enter him again!’ 26 After crying out and convulsing him terribly, it came out, and the boy was like a corpse, so that most of them said, ‘He is dead.’ 27 But Jesus took him by the hand and lifted him up, and he was able to stand. 28 When he had entered the house, his disciples asked him privately, ‘Why could we not cast it out?’ 29 He said to them, ‘This kind can come out only through prayer.’

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (21 February 2022) invites us to pray:

Let us pray for all those who are working to achieve social justice. May we all try to be just and merciful in our everyday life.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)