Forged identity papers from Warsaw 1941 in the name of Krystyna Szczepanska, a pseudonym for Edyta Rozenfeld, the grandmother of Oliver Sears … one of the exhibits in ‘The Objects of Love’ an exhibition in Dublin Castle (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022

Patrick Comerford

Today is Holocaust Memorial Day, marking the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz in 1945 and the beginning of the liberation of the concentration camps in Europe. Earlier this week I attended ‘The Objects of Love’ an exhibition in Dublin Castle organised by the Office of Public Works in association with Holocaust Awareness Ireland.

‘The Objects of Love’ is an exhibition of powerful mementoes that tell the story of one Jewish family before, during and after World War II. The exhibition in the Bedford Hall opened on 12 January, a fortnight before Holocaust Memorial Day, and this is a poignant exhibition telling the fate of individual lives torn asunder in Nazi-occupied Poland and beyond.

Their story is told through a curated collection of precious family objects, photographs and documents. The Dublin-based art dealer Oliver Sears vividly brings to life this extreme edge of European history where his mother Monika and grandmother Kryszia are the beating hearts of an epic and intimate story of love, loss, and survival.

Oliver Sears, who grew up in London and owns an art gallery in Dublin, is the founder of Holocaust Awareness Ireland. His family came from the Polish city of Lodz, which had a population of 200,000 Jews before the war.

He has painstakingly chronicled how their lives were torn apart following the Nazi invasion in 1939. He said: ‘They were ordinary people. It's just that fate intervened and ensured that they had extraordinary lives. This is my family story, told through my eyes, the only way I know how, using fragments of memory I have recorded, together with the collection of objects and documents, the emotional debris of dislocation and disaster.’

The items in the exhibition include forged identity papers belonging to his grandmother.

‘They show a passport sized photograph of my grandmother with freshly dyed blonde hair staring straight ahead. A new and necessary look to heighten her Aryan credentials, along with her acquired, nondescript Polish name and unlikely declared profession of ‘typist’.’

‘When I think about the Holocaust and what happened to my family, strangely I don't feel anger. It's humiliation. What could be more humiliating than having to pretend that you are something you are not, because your life depends on it.’

Oliver Sears hopes the exhibition raises awareness and understanding of a subject that ‘is still not widely known in Ireland.’ He says the exhibition is important to illustrate the generational impact the Holocaust had on families, and in the context of antisemitism that still persists today.

He explains how he felt he was honouring his family by bringing their story to Dublin Castle. ‘I think the fact that we were invited by the OPW to produce this exhibition at Dublin Castle gives us, in a nutshell, the imprimatur of the State. I do have a very keen sense of needing to honour my family. At an almost biblical level, they were humiliated.

‘Not only were they murdered, every trace that they ever existed was wiped out. So, there is a sense of triumph that I, somehow, at State-level can give them a voice, bring them back to life briefly, and give them a value that was stripped from them.’

In November 2020, he had found a cache of photographs and documents relating to his family in the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC.

By organising this exhibition, he says he can honour his family, he told The Irish Times. ‘You can have massive gaps in your family, there are all these ghosts. There are people who you never knew, who you should have known. Then there are the living ghosts, who are badly traumatised, who weave in and out of your childhood, some of whom you are related to.’

The forged identity papers of Oliver Sears’s grandmother Kryszia Wandstein (Edyta Rosenfeld). In spring 1943, Edyta bought forged identity papers that allowed her and her daughter Monika to live outside a ghetto.

When his grandmother and mother came to England in 1947, his grandmother married a Polish Jewish dentist who was stranded in London during the war. He had lost every single member of his family, including his pregnant wife. ‘He married my grandmother. He was the only grandfather I knew. I didn’t know he wasn’t my real grandfather until the day he died.’

The photographs from before the war are the most moving to Oliver Sears, as they show ordinary people, with hopes, dreams and aspirations, and that was all destroyed. However, he feels the exhibition is an act of resistance in itself, as the Nazis’ goal was to eradicate Jewish people completely. ‘It says: ‘No. Where are you, with your thousand-year reich? We are still here’.’

The exhibition was opened by Lenny Abrahamson and is accompanied by an audio narration and an illustrated booklet.

Speaking before the exhibition, the Minister at the OPW, Patrick O’Donovan, said: ‘The Holocaust represents an event at the limits, a core event in which a shared European memory is rooted that we in Ireland are part of. But it is only through our own personal engagement with the past that we can understand its legacy and continued relevance to our present and future. This exhibition particularises the experience of one family and offers us a unique opportunity to both relate to and bear witness to the fate of those persecuted by the Nazis.’

The exhibition continues until 13 February 2022. Opening times daily are 10 am to 5 pm (closed 1 to 2), and admission is free.

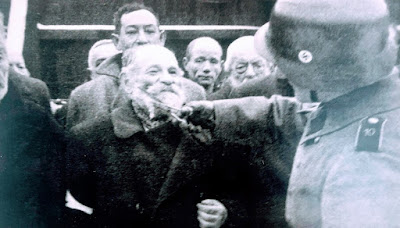

Nazis humiliating Jews publicly in the Kraków ghetto in 1941

27 January 2022

With the Saints through Christmas (33):

27 January 2022, Saint Paul’s Cathedral, Mdina

Saint Paul’s Cathedral, Mdina, in central Malta, facing onto Saint Paul’s Square (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Patrick Comerford

I was in Malta last week, and in Valletta it seems as though every street – or every second street – inside the walls of the capital of Malta, is named after a saint.

I am in Birmingham today, attending to some family matters. But, before a busy day begins, I am taking some time early this morning for prayer, reflection and reading.

I have been continuing my Prayer Diary on my blog each morning, reflecting in these ways:

1, Reflections on a saint remembered in the calendars of the Church during the Season of Christmas, which continues until Candlemas or the Feast of the Presentation (2 February);

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

This week, I am continuing to reflect on saints and their association with prominent churches or notable street names in Malta, which I visited last week. Tuesday was the Feast of the Conversion of Saint Paul, and during this week I I have already reflected on Saint Paul’s Church at Saint Paul’s Bay (25 January) and Saint Paul’s Pro-Cathedral (Anglican), Valletta (26 January). This morning I am reflecting on Saint Paul’s Cathedral, Mdina.

The Metropolitan Cathedral of Saint Paul (Il-Katidral Metropolitan ta’ San Pawl), commonly known as Saint Paul’s Cathedral or the Mdina Cathedral, is the Roman Catholic cathedral in Mdina, in central Malta.

The cathedral was founded in the 12th century. It is the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Malta, although since the 19th century it has shared this function with Saint John’s Co-Cathedral in Valletta.

According to tradition, the site of Mdina cathedral was originally occupied by a palace belonging to Saint Publius, the Roman governor of Melite who greeted the Apostle Paul after he was shipwrecked in Malta. According to the Acts of the Apostles, Saint Paul cured Publius’ father and many other sick people on the island (see Acts 28: 1-10).

The first cathedral on the site is said to have been dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary. But it fell into disrepair during the Arab period, when the churches in Melite were looted after the Aghlabid invasion in 870. In Arab times, the site was used as a mosque.

After the Norman invasion in 1091, Christianity was re-established on the Maltese Islands, and a cathedral dedicated to Saint Paul was built in the 12th and 13th centuries. The cathedral was built in the Gothic and Romanesque styles, and was enlarged and modified a number of times.

Bishop Miguel Jerónimo de Molina and the cathedral chapter decided in 1679 to replace the mediaeval choir with one built in the Baroque style. The architect Lorenzo Gafà was designed and oversaw the new building.

The cathedral was severely damaged a few years later in the 1693 Sicily earthquake. Although parts of the building were not damaged, it was decided to dismantle the old cathedral and rebuild it in the Baroque style to a design of Lorenzo Gafà, incorporating the choir and sacristy, which had survived the earthquake, into the new cathedral.

Work began in 1696, and the building was almost complete by 1702. It was consecrated by Bishop Davide Cocco Palmieri on 8 October 1702. The cathedral was fully completed on 24 October 1705, when work on the dome was finished. The building is regarded as Gafà's masterpiece.

Saint Paul’s Cathedral is built in the Baroque style, with some influences from native Maltese architecture. The main façade faces Saint Paul’s Square and it is set on a low parvis approached by three steps.

The façade is cleanly divided into three bays by pilasters of Corinthian and Composite orders. The central bay is set forward, and it contains the main doorway, surmounted by the coats of arms of the city of Mdina, Grand Master Ramon Perellos y Roccaful and Bishop Davide Cocco Palmieri, all sculpted by Giuseppe Darmanin.

The coloured coat of arms of the incumbent archbishop (Archbishop Charles Scicluna) is placed just below the arms of Mdina. A round-headed window is set in the upper story above the doorway, and the façade is topped by a triangular pediment. Bell towers originally containing six bells are located at both corners of the façade. It has an octagonal dome, with eight stone scrolls above a high drum leading up to a lantern.

The cathedral has a Latin cross plan with a vaulted nave, two aisles and two side chapels. Most of the cathedral floor has inlaid tombstones or commemorative marble slabs, similar to those in Saint John’s Co-Cathedral, Valletta and the Cathedral of the Assumption in Victoria, Gozo. Several bishops and canons, as well as laymen from noble families, are buried in the cathedral.

The frescoes in the ceiling depict the life of Saint Paul and were painted by the Sicilian painters Vincenzo, Antonio and Francesco Manno in 1794. The Manno brothers also painted frescoes on the dome, but these were destroyed during repair works after an earthquake in 1856.

A new fresco was painted on the dome by Giuseppe Gallucci in 1860, and it was later restored by Giuseppe Calì. Gallucci’s and Calì’s paintings were destroyed due to urgent repair works in 1927, and they were later replaced by a fresco depicting The Glory of Saint Peter and Saint Paul by Mario Caffaro Rore. The ceiling was restored by Samuel Bugeja in 1956.

Three late 19th century stained glass windows in the cathedral are the work of Victor Gesta’s workshop.

Many artefacts from the pre-1693 cathedral survived the earthquake and were reused to decorate the new cathedral. These include a late Gothic or early Renaissance baptismal font dating from 1495, the old cathedral’s main door that was made in 1530, some 15th-century choir stalls, and a number of paintings.

The cathedral aisles, chapels and sacristy contain several paintings and frescoes, including works by Mattia Preti and his bottega, Francesco Grandi, Domenico Bruschi, Pietro Gagliardi, Bartolomeo Garagona, Francesco Zahra, Luigi Moglia and Alessio Erardi. The altarpiece by Mattia Preti depicts the Conversion of Saint Paul on the Road to Damascus.

br /> Some of the marble used to decorate the cathedral was taken from the Roman ruins of Carthage and Melite. Sculptors and other artists whose works decorate the cathedral include Giuseppe Valenti, Claudio Durante, Alessandro Algardi and Vincent Apap.

Some mediaeval houses south of the cathedral were demolished in the late 1720s to make way for a square, the Bishop’s Palace and the Seminary, now the Cathedral Museum. The square in front of the cathedral was enlarged in the early 19th century after the demolition of some more mediaeval buildings.

The cathedral was damaged in another earthquake in 1856, and the 18th-century frescoes on the dome were destroyed.

Today, the cathedral is a Grade 1 national monument and is listed on the National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands.

Inside Saint Paul’s Cathedral in Mdina, facing the liturgical east (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Mark 4: 21-25:

21 He said to them, ‘Is a lamp brought in to be put under the bushel basket, or under the bed, and not on the lampstand? 22 For there is nothing hidden, except to be disclosed; nor is anything secret, except to come to light. 23 Let anyone with ears to hear listen!’ 24 And he said to them, ‘Pay attention to what you hear; the measure you give will be the measure you get, and still more will be given you. 25 For to those who have, more will be given; and from those who have nothing, even what they have will be taken away.’

Inside Saint Paul’s Cathedral, Mdina, facing the liturgical west (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (27 January 2022, Holocaust Remembrance Day) invites us to pray:

Today we remember the atrocities of the Holocaust. May we continue to commemorate these tragic events in the hope that it will never happen again..

Yesterday: Saint Paul’s Pro-Cathedral (Anglican), Valletta

Tomorrow: The Collegiate Parish Church of Saint Paul’s Shipwreck, Valletta

The High Altar in Saint Paul’s Cathedral, Mdina (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

In the side aisles in Saint Paul’s Cathedral, Mdina (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Patrick Comerford

I was in Malta last week, and in Valletta it seems as though every street – or every second street – inside the walls of the capital of Malta, is named after a saint.

I am in Birmingham today, attending to some family matters. But, before a busy day begins, I am taking some time early this morning for prayer, reflection and reading.

I have been continuing my Prayer Diary on my blog each morning, reflecting in these ways:

1, Reflections on a saint remembered in the calendars of the Church during the Season of Christmas, which continues until Candlemas or the Feast of the Presentation (2 February);

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

This week, I am continuing to reflect on saints and their association with prominent churches or notable street names in Malta, which I visited last week. Tuesday was the Feast of the Conversion of Saint Paul, and during this week I I have already reflected on Saint Paul’s Church at Saint Paul’s Bay (25 January) and Saint Paul’s Pro-Cathedral (Anglican), Valletta (26 January). This morning I am reflecting on Saint Paul’s Cathedral, Mdina.

The Metropolitan Cathedral of Saint Paul (Il-Katidral Metropolitan ta’ San Pawl), commonly known as Saint Paul’s Cathedral or the Mdina Cathedral, is the Roman Catholic cathedral in Mdina, in central Malta.

The cathedral was founded in the 12th century. It is the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Malta, although since the 19th century it has shared this function with Saint John’s Co-Cathedral in Valletta.

According to tradition, the site of Mdina cathedral was originally occupied by a palace belonging to Saint Publius, the Roman governor of Melite who greeted the Apostle Paul after he was shipwrecked in Malta. According to the Acts of the Apostles, Saint Paul cured Publius’ father and many other sick people on the island (see Acts 28: 1-10).

The first cathedral on the site is said to have been dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary. But it fell into disrepair during the Arab period, when the churches in Melite were looted after the Aghlabid invasion in 870. In Arab times, the site was used as a mosque.

After the Norman invasion in 1091, Christianity was re-established on the Maltese Islands, and a cathedral dedicated to Saint Paul was built in the 12th and 13th centuries. The cathedral was built in the Gothic and Romanesque styles, and was enlarged and modified a number of times.

Bishop Miguel Jerónimo de Molina and the cathedral chapter decided in 1679 to replace the mediaeval choir with one built in the Baroque style. The architect Lorenzo Gafà was designed and oversaw the new building.

The cathedral was severely damaged a few years later in the 1693 Sicily earthquake. Although parts of the building were not damaged, it was decided to dismantle the old cathedral and rebuild it in the Baroque style to a design of Lorenzo Gafà, incorporating the choir and sacristy, which had survived the earthquake, into the new cathedral.

Work began in 1696, and the building was almost complete by 1702. It was consecrated by Bishop Davide Cocco Palmieri on 8 October 1702. The cathedral was fully completed on 24 October 1705, when work on the dome was finished. The building is regarded as Gafà's masterpiece.

Saint Paul’s Cathedral is built in the Baroque style, with some influences from native Maltese architecture. The main façade faces Saint Paul’s Square and it is set on a low parvis approached by three steps.

The façade is cleanly divided into three bays by pilasters of Corinthian and Composite orders. The central bay is set forward, and it contains the main doorway, surmounted by the coats of arms of the city of Mdina, Grand Master Ramon Perellos y Roccaful and Bishop Davide Cocco Palmieri, all sculpted by Giuseppe Darmanin.

The coloured coat of arms of the incumbent archbishop (Archbishop Charles Scicluna) is placed just below the arms of Mdina. A round-headed window is set in the upper story above the doorway, and the façade is topped by a triangular pediment. Bell towers originally containing six bells are located at both corners of the façade. It has an octagonal dome, with eight stone scrolls above a high drum leading up to a lantern.

The cathedral has a Latin cross plan with a vaulted nave, two aisles and two side chapels. Most of the cathedral floor has inlaid tombstones or commemorative marble slabs, similar to those in Saint John’s Co-Cathedral, Valletta and the Cathedral of the Assumption in Victoria, Gozo. Several bishops and canons, as well as laymen from noble families, are buried in the cathedral.

The frescoes in the ceiling depict the life of Saint Paul and were painted by the Sicilian painters Vincenzo, Antonio and Francesco Manno in 1794. The Manno brothers also painted frescoes on the dome, but these were destroyed during repair works after an earthquake in 1856.

A new fresco was painted on the dome by Giuseppe Gallucci in 1860, and it was later restored by Giuseppe Calì. Gallucci’s and Calì’s paintings were destroyed due to urgent repair works in 1927, and they were later replaced by a fresco depicting The Glory of Saint Peter and Saint Paul by Mario Caffaro Rore. The ceiling was restored by Samuel Bugeja in 1956.

Three late 19th century stained glass windows in the cathedral are the work of Victor Gesta’s workshop.

Many artefacts from the pre-1693 cathedral survived the earthquake and were reused to decorate the new cathedral. These include a late Gothic or early Renaissance baptismal font dating from 1495, the old cathedral’s main door that was made in 1530, some 15th-century choir stalls, and a number of paintings.

The cathedral aisles, chapels and sacristy contain several paintings and frescoes, including works by Mattia Preti and his bottega, Francesco Grandi, Domenico Bruschi, Pietro Gagliardi, Bartolomeo Garagona, Francesco Zahra, Luigi Moglia and Alessio Erardi. The altarpiece by Mattia Preti depicts the Conversion of Saint Paul on the Road to Damascus.

br /> Some of the marble used to decorate the cathedral was taken from the Roman ruins of Carthage and Melite. Sculptors and other artists whose works decorate the cathedral include Giuseppe Valenti, Claudio Durante, Alessandro Algardi and Vincent Apap.

Some mediaeval houses south of the cathedral were demolished in the late 1720s to make way for a square, the Bishop’s Palace and the Seminary, now the Cathedral Museum. The square in front of the cathedral was enlarged in the early 19th century after the demolition of some more mediaeval buildings.

The cathedral was damaged in another earthquake in 1856, and the 18th-century frescoes on the dome were destroyed.

Today, the cathedral is a Grade 1 national monument and is listed on the National Inventory of the Cultural Property of the Maltese Islands.

Inside Saint Paul’s Cathedral in Mdina, facing the liturgical east (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Mark 4: 21-25:

21 He said to them, ‘Is a lamp brought in to be put under the bushel basket, or under the bed, and not on the lampstand? 22 For there is nothing hidden, except to be disclosed; nor is anything secret, except to come to light. 23 Let anyone with ears to hear listen!’ 24 And he said to them, ‘Pay attention to what you hear; the measure you give will be the measure you get, and still more will be given you. 25 For to those who have, more will be given; and from those who have nothing, even what they have will be taken away.’

Inside Saint Paul’s Cathedral, Mdina, facing the liturgical west (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (27 January 2022, Holocaust Remembrance Day) invites us to pray:

Today we remember the atrocities of the Holocaust. May we continue to commemorate these tragic events in the hope that it will never happen again..

Yesterday: Saint Paul’s Pro-Cathedral (Anglican), Valletta

Tomorrow: The Collegiate Parish Church of Saint Paul’s Shipwreck, Valletta

The High Altar in Saint Paul’s Cathedral, Mdina (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

In the side aisles in Saint Paul’s Cathedral, Mdina (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)