All Saints’ Day … the Lamb on the Throne surrounded by the angels and saints

Let us pray:

The response to ‘God of Love’ is ‘grant our prayer.’

God of love

grant our prayer.

God of the past,

on this feast of All Saints

we remember before you, with thanks,

the lives of those Christians who have gone before us:

the great leaders and thinkers,

those who have died for their faith,

those whose goodness transformed all they did;

Give us grace to follow their example and continue their work.

God of love

grant our prayer.

God of the present,

on this feast of All Saints

we remember before you

those who have more recently died,

giving thanks for their lives and example and for all that they have meant to us.

We pray for those who grieve

and for all who suffer throughout the world:

for the hungry, the sick, the victims of violence and persecution.

God of love

grant our prayer.

God of the future,

on this feast of All Saints

we remember before you the newest generation of your saints,

and pray for the future of the church

and for all who nurture and encourage faith.

God of love

grant our prayer.

We give you thanks

for the whole company of your saints

with whom in fellowship we join our prayers and praises

in the name of Jesus Christ

Amen.

Merciful Father …

All Saints depicted in the window in Saint Columb’s Cathedral, Derry, in memory of Canon Richard Babington (1837-1893) of All Saints’ Church, Clooney, Derry (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

31 October 2021

‘The souls of the righteous

are in the hand of God, no

torment will ever touch them’

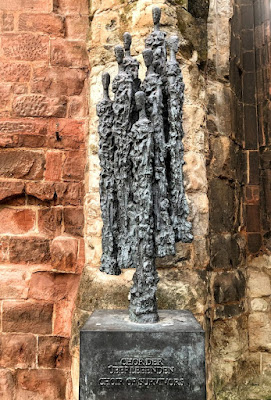

Saints and Martyrs … the ten martyrs of the 20th century above the West Door of Westminster Abbey (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

Sunday 31 October 2021, All Saints’ Sunday.

Saint Mary’s Church, Askeaton, Co Limerick

11 a.m.: The Parish Eucharist (Holy Communion 2, United Group Service)

The Readings: Wisdom 3: 1-9; Psalm 24; Revelation 21: 1-6a; John 11: 32-44.

There is a link to the readings HERE.

Saints and Angels in the glass wall by John Hutton at the entrance to Coventry Cathedral (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

May I speak to you in the name of God, + Father, Son and Holy Spirit, Amen.

November is a month when we traditionally remember the saints, the Communion of Saints, those we love and who are now gathered around the throne of God, those who have died and who we still love.

As the evenings close in, as the last autumn leaves fall from the trees, it is natural to remember the dead and the fallen, with love and affection.

All Saints’ Day on 1 November is one of the 12 Principal Feasts of the Church. In many parts of the Anglican Communion, 2 November is All Souls’ Day, the ‘Commemoration of the Faithful Departed’ (Common Worship, p 15). In Ireland, 6 November traditionally recalls ‘All Saints of Ireland.’ Remembrance Day is on 11 November, and this year we mark Remembrance Sunday on 14 November.

Hallowe’en is not a day to associate with ghouls and ghosts, still less for making light or making fun of evil. There was a disturbing discussion on Joe Duffy’s Live Line show last Thursday of Nazi uniforms being hired out as Hallowe’en costumes. One contributor to the show even thought this was funny. How can anyone make fun of the Holocaust and the mass murders of World War II? How can anyone want to link the Nazis with saints, except as martyrs and victims?

Hallowe’en is the day before we remember the Hallowed, the blessed, the saints, who are models for our lives, our Christian lifestyle today.

When he was Dean of Liverpool, Archbishop Justin Welby organised a Hallowe’en service he labelled ‘Night of the Living Dead’. At first, it sounds ghoulish. But that’s what it is … the Night of the Living Dead’. We believe the dead we love are still caught up in the love of God and are alive in Christ.

Indeed, saints do not need to be dead to be examples of ‘holy living and holy dying’ (Jeremy Taylor).

Saint Paul regularly refers in his letters to fellow Christians as ‘saints.’ Saints Alive!

Yet we have been shy, reluctant, perhaps even fearful, in the Church of Ireland when it comes to recalling, commemorating and celebrating the saints. We only have to compare the calendars of the Church of Ireland and the Church of England.

Perhaps we were too afraid in the past of being seen to pray to the saints, or to pray for the dead. But, really, these are quite different to finding examples of godly living among Christians from the past, and expressing confidence that the dead we have loved are now committed to God’s love.

Our psalm this morning (Psalm 24) talks about those who can enter the presence of God. The response provided in the Lectionary is a quotation from the first reading, ‘The souls of the righteous are in the hand of God, no torment will ever touch them’ (Wisdom 3: 1).

Is anyone this morning able to name the patron saints of Ireland? (Answer: Saint Patrick, Saint Brigid and Saint Columba or Colmcille?)

Apart from Saint Patrick, do you know the saints’ day for the other two? (Answer: Brigid, 1 February; Columba, 9 June)

Does anyone remember who is the patron saint of the Diocese of Limerick? (Answer: Munchin, 2 January)

Yet the Church of England sees the calendar of saints as a living calendar, something that is added to as we find more appropriate examples of Christian living for today.

Saints do not have to be martyrs. But in recent years Oscar Romero was canonised and there was a major commemoration in Westminster Abbey of Oscar Romero to mark his 100th birthday.

Saints do not have to be canonised. Modern martyrs may include Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Martin Luther King, or Heather Heyer, the civil rights activist killed by far-right neo-Nazis and racists in Charlottesville, Kentucky, in 2017.

Many of us we know people who handed on the faith to us – teachers, grandparents, perhaps neighbours – even though some may be long dead yet are part of our vision of the Communion of Saints.

Saints do not have to live a perfect life … none of us is without sin, and none of us is beyond redemption. Some of the saints carved on the West Front of Westminster Abbey might have been very surprised to know they were going to appear there. But their lives in sum total are what we are asked to think about.

They are: Maximilian Kolbe, Manche Masemola, Archbishop Janani Luwum, Grand Duchess Elizabeth, Martin Luther King, Oscar Romero, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Esther John, Lucian Tapiedi, and Wang Zhiming.

Some years ago, I asked students to share stories of their favourite ‘saints and heroes.’ They included an interesting array of people, some still living, including Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who celebrated his 90th birthday this year.

In the back-page interviews in the Church Times, people are sometimes asked who they would like to be locked into a church with for a few hours.

Who are your favourite saints? (time for answers).

Who would you like to learn from a little more when it comes to living the Christian life?

In the Apostles’ Creed, we confess our faith which includes our belief in ‘the communion of saints’ and ‘the resurrection of the body.’ In a few moments, we confess our faith in the words of the Nicene Creed, including our belief in ‘the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come.

Then there is an opportunity to recall the saints in our lives, in our own personal calendars, and to recall those we have committed to God’s love and who are part of ‘the communion of saints’.

We have had seven funerals in this group of parishes since last Christmas. There are seven candles on the altar with a single name on each one. In addition, there are two bowls of water here, in which we can place our nightlights to remember those we still love.

And throughout the month of November, there are opportunities to include their names in our weekly, Sunday intercessions.

In the meantime, ‘The souls of the righteous are in the hand of God, no torment will ever touch them.’

May all we think, say and do be to the praise, honour and glory of God, + Father, Son and Holy Spirit, Amen.

‘The Tree of the Church’ (1895) by Charles Kempe … a window in the south transept of Lichfield Cathedral shows Christ surrounded by the saints (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

John 11: 32-44 (NRSVA):

32 When Mary came where Jesus was and saw him, she knelt at his feet and said to him, ‘Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died.’ 33 When Jesus saw her weeping, and the Jews who came with her also weeping, he was greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved. 34 He said, ‘Where have you laid him?’ They said to him, ‘Lord, come and see.’ 35 Jesus began to weep. 36 So the Jews said, ‘See how he loved him!’ 37 But some of them said, ‘Could not he who opened the eyes of the blind man have kept this man from dying?’

38 Then Jesus, again greatly disturbed, came to the tomb. It was a cave, and a stone was lying against it. 39 Jesus said, ‘Take away the stone.’ Martha, the sister of the dead man, said to him, ‘Lord, already there is a stench because he has been dead for four days.’ 40 Jesus said to her, ‘Did I not tell you that if you believed, you would see the glory of God?’ 41 So they took away the stone. And Jesus looked upwards and said, ‘Father, I thank you for having heard me. 42 I knew that you always hear me, but I have said this for the sake of the crowd standing here, so that they may believe that you sent me.’ 43 When he had said this, he cried with a loud voice, ‘Lazarus, come out!’ 44 The dead man came out, his hands and feet bound with strips of cloth, and his face wrapped in a cloth. Jesus said to them, ‘Unbind him, and let him go.’

The Great West Window in Saint Editha’s Church, Tamworth, ‘Revelation of the Holy City,’ was designed by Alan Younger, who was inspired by Revelation 21 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Liturgical colour: White

Penitential Kyries:

Lord, you are gracious and compassionate.

Lord, have mercy.

Lord, have mercy.

You are loving to all,

and your mercy is over all your creation.

Christ, have mercy.

Christ, have mercy.

Your faithful servants bless your name,

and speak of the glory of your kingdom.

Lord, have mercy.

Lord, have mercy.

The Collect:

Almighty God,

you have knit together your elect

in one communion and fellowship

in the mystical body of your Son Christ our Lord:

Grant us grace so to follow your blessed saints

in all virtuous and godly living

that we may come to those inexpressible joys

that you have prepared for those who truly love you;

through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Introduction to the Peace:

We are fellow citizens with the saints

and the household of God,

through Christ our Lord,

who came and preached peace to those who were far off

and those who were near (Ephesians 2: 19, 17).

The Preface:

In the saints

you have given us an example of godly living,

that rejoicing in their fellowship,

we may run with perseverance the race that is set before us,

and with them receive the unfading crown of glory …

Post-Communion Prayer:

God, the source of all holiness

and giver of all good things:

May we who have shared at this table

as strangers and pilgrims here on earth

be welcomed with all your saints

to the heavenly feast on the day of your kingdom;

through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Blessing:

God give you grace

to share the inheritance of all his saints in glory …

Christ the Pantocrator surrounded by the saints in the Dome of the Church of Analipsi in Georgioupoli, Crete (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Hymns:

459, For all the saints, who from their labours rest (CD 27)

466, Here from all nations, all tongues, and all peoples (CD 27)

468, How shall I sing that majesty (CD supplied)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Material from the Book of Common Prayer is copyright © 2004, Representative Body of the Church of Ireland.

Patrick Comerford

Sunday 31 October 2021, All Saints’ Sunday.

Saint Mary’s Church, Askeaton, Co Limerick

11 a.m.: The Parish Eucharist (Holy Communion 2, United Group Service)

The Readings: Wisdom 3: 1-9; Psalm 24; Revelation 21: 1-6a; John 11: 32-44.

There is a link to the readings HERE.

Saints and Angels in the glass wall by John Hutton at the entrance to Coventry Cathedral (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

May I speak to you in the name of God, + Father, Son and Holy Spirit, Amen.

November is a month when we traditionally remember the saints, the Communion of Saints, those we love and who are now gathered around the throne of God, those who have died and who we still love.

As the evenings close in, as the last autumn leaves fall from the trees, it is natural to remember the dead and the fallen, with love and affection.

All Saints’ Day on 1 November is one of the 12 Principal Feasts of the Church. In many parts of the Anglican Communion, 2 November is All Souls’ Day, the ‘Commemoration of the Faithful Departed’ (Common Worship, p 15). In Ireland, 6 November traditionally recalls ‘All Saints of Ireland.’ Remembrance Day is on 11 November, and this year we mark Remembrance Sunday on 14 November.

Hallowe’en is not a day to associate with ghouls and ghosts, still less for making light or making fun of evil. There was a disturbing discussion on Joe Duffy’s Live Line show last Thursday of Nazi uniforms being hired out as Hallowe’en costumes. One contributor to the show even thought this was funny. How can anyone make fun of the Holocaust and the mass murders of World War II? How can anyone want to link the Nazis with saints, except as martyrs and victims?

Hallowe’en is the day before we remember the Hallowed, the blessed, the saints, who are models for our lives, our Christian lifestyle today.

When he was Dean of Liverpool, Archbishop Justin Welby organised a Hallowe’en service he labelled ‘Night of the Living Dead’. At first, it sounds ghoulish. But that’s what it is … the Night of the Living Dead’. We believe the dead we love are still caught up in the love of God and are alive in Christ.

Indeed, saints do not need to be dead to be examples of ‘holy living and holy dying’ (Jeremy Taylor).

Saint Paul regularly refers in his letters to fellow Christians as ‘saints.’ Saints Alive!

Yet we have been shy, reluctant, perhaps even fearful, in the Church of Ireland when it comes to recalling, commemorating and celebrating the saints. We only have to compare the calendars of the Church of Ireland and the Church of England.

Perhaps we were too afraid in the past of being seen to pray to the saints, or to pray for the dead. But, really, these are quite different to finding examples of godly living among Christians from the past, and expressing confidence that the dead we have loved are now committed to God’s love.

Our psalm this morning (Psalm 24) talks about those who can enter the presence of God. The response provided in the Lectionary is a quotation from the first reading, ‘The souls of the righteous are in the hand of God, no torment will ever touch them’ (Wisdom 3: 1).

Is anyone this morning able to name the patron saints of Ireland? (Answer: Saint Patrick, Saint Brigid and Saint Columba or Colmcille?)

Apart from Saint Patrick, do you know the saints’ day for the other two? (Answer: Brigid, 1 February; Columba, 9 June)

Does anyone remember who is the patron saint of the Diocese of Limerick? (Answer: Munchin, 2 January)

Yet the Church of England sees the calendar of saints as a living calendar, something that is added to as we find more appropriate examples of Christian living for today.

Saints do not have to be martyrs. But in recent years Oscar Romero was canonised and there was a major commemoration in Westminster Abbey of Oscar Romero to mark his 100th birthday.

Saints do not have to be canonised. Modern martyrs may include Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Martin Luther King, or Heather Heyer, the civil rights activist killed by far-right neo-Nazis and racists in Charlottesville, Kentucky, in 2017.

Many of us we know people who handed on the faith to us – teachers, grandparents, perhaps neighbours – even though some may be long dead yet are part of our vision of the Communion of Saints.

Saints do not have to live a perfect life … none of us is without sin, and none of us is beyond redemption. Some of the saints carved on the West Front of Westminster Abbey might have been very surprised to know they were going to appear there. But their lives in sum total are what we are asked to think about.

They are: Maximilian Kolbe, Manche Masemola, Archbishop Janani Luwum, Grand Duchess Elizabeth, Martin Luther King, Oscar Romero, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Esther John, Lucian Tapiedi, and Wang Zhiming.

Some years ago, I asked students to share stories of their favourite ‘saints and heroes.’ They included an interesting array of people, some still living, including Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who celebrated his 90th birthday this year.

In the back-page interviews in the Church Times, people are sometimes asked who they would like to be locked into a church with for a few hours.

Who are your favourite saints? (time for answers).

Who would you like to learn from a little more when it comes to living the Christian life?

In the Apostles’ Creed, we confess our faith which includes our belief in ‘the communion of saints’ and ‘the resurrection of the body.’ In a few moments, we confess our faith in the words of the Nicene Creed, including our belief in ‘the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come.

Then there is an opportunity to recall the saints in our lives, in our own personal calendars, and to recall those we have committed to God’s love and who are part of ‘the communion of saints’.

We have had seven funerals in this group of parishes since last Christmas. There are seven candles on the altar with a single name on each one. In addition, there are two bowls of water here, in which we can place our nightlights to remember those we still love.

And throughout the month of November, there are opportunities to include their names in our weekly, Sunday intercessions.

In the meantime, ‘The souls of the righteous are in the hand of God, no torment will ever touch them.’

May all we think, say and do be to the praise, honour and glory of God, + Father, Son and Holy Spirit, Amen.

‘The Tree of the Church’ (1895) by Charles Kempe … a window in the south transept of Lichfield Cathedral shows Christ surrounded by the saints (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

John 11: 32-44 (NRSVA):

32 When Mary came where Jesus was and saw him, she knelt at his feet and said to him, ‘Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died.’ 33 When Jesus saw her weeping, and the Jews who came with her also weeping, he was greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved. 34 He said, ‘Where have you laid him?’ They said to him, ‘Lord, come and see.’ 35 Jesus began to weep. 36 So the Jews said, ‘See how he loved him!’ 37 But some of them said, ‘Could not he who opened the eyes of the blind man have kept this man from dying?’

38 Then Jesus, again greatly disturbed, came to the tomb. It was a cave, and a stone was lying against it. 39 Jesus said, ‘Take away the stone.’ Martha, the sister of the dead man, said to him, ‘Lord, already there is a stench because he has been dead for four days.’ 40 Jesus said to her, ‘Did I not tell you that if you believed, you would see the glory of God?’ 41 So they took away the stone. And Jesus looked upwards and said, ‘Father, I thank you for having heard me. 42 I knew that you always hear me, but I have said this for the sake of the crowd standing here, so that they may believe that you sent me.’ 43 When he had said this, he cried with a loud voice, ‘Lazarus, come out!’ 44 The dead man came out, his hands and feet bound with strips of cloth, and his face wrapped in a cloth. Jesus said to them, ‘Unbind him, and let him go.’

The Great West Window in Saint Editha’s Church, Tamworth, ‘Revelation of the Holy City,’ was designed by Alan Younger, who was inspired by Revelation 21 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Liturgical colour: White

Penitential Kyries:

Lord, you are gracious and compassionate.

Lord, have mercy.

Lord, have mercy.

You are loving to all,

and your mercy is over all your creation.

Christ, have mercy.

Christ, have mercy.

Your faithful servants bless your name,

and speak of the glory of your kingdom.

Lord, have mercy.

Lord, have mercy.

The Collect:

Almighty God,

you have knit together your elect

in one communion and fellowship

in the mystical body of your Son Christ our Lord:

Grant us grace so to follow your blessed saints

in all virtuous and godly living

that we may come to those inexpressible joys

that you have prepared for those who truly love you;

through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Introduction to the Peace:

We are fellow citizens with the saints

and the household of God,

through Christ our Lord,

who came and preached peace to those who were far off

and those who were near (Ephesians 2: 19, 17).

The Preface:

In the saints

you have given us an example of godly living,

that rejoicing in their fellowship,

we may run with perseverance the race that is set before us,

and with them receive the unfading crown of glory …

Post-Communion Prayer:

God, the source of all holiness

and giver of all good things:

May we who have shared at this table

as strangers and pilgrims here on earth

be welcomed with all your saints

to the heavenly feast on the day of your kingdom;

through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Blessing:

God give you grace

to share the inheritance of all his saints in glory …

Christ the Pantocrator surrounded by the saints in the Dome of the Church of Analipsi in Georgioupoli, Crete (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Hymns:

459, For all the saints, who from their labours rest (CD 27)

466, Here from all nations, all tongues, and all peoples (CD 27)

468, How shall I sing that majesty (CD supplied)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Material from the Book of Common Prayer is copyright © 2004, Representative Body of the Church of Ireland.

Praying in Ordinary Time 2021:

155, Methodist Church, Tamworth Street, Lichfield

Lichfield Methodist Church, on the corner of Tamworth Street and Lombard Street … opened on 20 April 1892 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

Patrick Comerford

Today is the Fourth Sunday before Advent (31 October 2021), but is being marked in this group of parishes as All Saints’ Sunday. I am presiding and preaching at the Parish Eucharist at 11 a.m. in Saint Mary’s Church, Askeaton, a united service for the Rathkeale and Kilnaughtin Group of Parishes, and later in the afternoon I am taking part in the farewell service for Bishop Kenneth Kearon in Saint Mary’s Cathedral, Limerick.

Before the day gets busy, I am taking a little time this morning for prayer, reflection and reading. Each morning in the time in the Church Calendar known as Ordinary Time, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, photographs of a church or place of worship;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

My theme last week was churches in Lichfield, and this week’s theme is Methodist churches. These two themes are linked this morning (31 October 2021) with my choice of Lichfield Methodist Church on Tamworth Street, Lichfield.

The Wesleyan Methodist Church on Tamworth Street, Lichfield, at its opening in 1892

The Methodist church at the city end of Tamworth Street, at the junction with Lombard Street, has undergone extensive redevelopment in recent years, with the addition of schoolrooms and meeting rooms. This is the home church of the Tamworth and Lichfield Circuit, which includes the Methodist churches in Lichfield, Alrewas Glascote, Shenstone and Tamworth.

Although John Wesley visited Lichfield three times in 1755, 1756 and 1777, he never preached in Lichfield, and the first Methodist chapel in Lichfield was not registered until 1811.

A warehouse at Gallows Wharf was registered in 1811 as places of worship by Joshua Kidger. A chapel was built in Lombard Street in 1813, and was opened in 1814 by Dr Adam Clarke in 1814.

There is evidence of another Wesleyan chapel that opened in 1815 and that in Wade Street in 1815 and that was still in use as late as 1837. During the 1851 Religious Census, the chapel in Lombard Street recorded attendances of 22 in the morning and 41 in the evening, but referred to congregations of 130 in the winter months.

Lichfield was in the Burton upon Trent Circuit until 1886, when the Tamworth and Lichfield Circuit was formed.

A site for a new chapel was bought in 1891. The ‘new’ Lichfield Wesleyan Methodist Church on Tamworth Street was built in the Victorian Gothic ornamental style to designs by Thomas Guest of Birmingham.

The foundation stones were laid on 12 August 1891 by Samuel Haynes, Mayor of Lichfield, and Reginald Stanley (1838-1914) of Nuneaton, a prominent Methodist business figure who owned brickyards, collieries, and an engineering firm. The builder was Edward Williams of Tamworth. The stone-laying ceremony was followed by a tea in the Guildhall.

The church was opened on 20 April 1892 by the President of the Methodist Conference, the Revd Dr Thomas Bowman Stephenson (1839-1912), regarded as ‘the architect of a more socially-minded Methodism’.

This new church replaced the Lombard Street chapel, but that building was not sold until 1921, after Tamworth House next to the new chapel was bought. New Sunday School premises were opened in 1924 and a period of growth led to extensions of the premises in 1972.

Meanwhile, there were Primitive Methodists in Lichfield from 1820 at Greenhill. They registered a schoolroom in Saint Mary’s parish for worship in 1831 and opened their own chapel in George Lane in 1847/1848. The George Lane chapel closed and was sold in 1934, when the members joined the Wesleyan Methodists at Tamworth Street.

In 1826, the Methodist New Connexion registered a barn in Sandford Street that had formerly been used by the Congregationalists. It was replaced in 1833 by a chapel in Queen Street, but this was sold in 1859 when the congregation disbanded.

Major alterations were made to the church on Tamworth Street in 1982, when the sanctuary was relocated at the Tamworth Street end and with new entrance facing Tamworth House. The pews were replaced by chairs from a prison on the Isle of Wight prison. But the loss of the choir stalls also led to the demise of the choir itself.

Meanwhile, a growth in population in Lichfield in this period, particularly with the development of the Boley Park estate, was matched by a growing membership, which reached 348 in 1987.

The church buildings were refurbished in 1998-1999 and again in 2012. The glass doors at the main entrance of the church mean that on a Sunday morning the church is looking out onto Lichfield, and Lichfield is looking into the church at worship … an architecturally perfect way to express the mission of the Church.

The Minister of Lichfield Methodist Church is the Revd Roger Baker, Superintendent of the Tamworth and Lichfield Methodist Circuit, and Sunday services are at 10 a.m.

The foundation stone was laid on 12 August 1891 by Samuel Haynes, Mayor of Lichfield (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

Mark 12: 28-34 (NRSVA):

28 One of the scribes came near and heard them disputing with one another, and seeing that he answered them well, he asked him, ‘Which commandment is the first of all?’ 29 Jesus answered, ‘The first is, “Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is one; 30 you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength.” 31 The second is this, “You shall love your neighbour as yourself.” There is no other commandment greater than these.’ 32 Then the scribe said to him, ‘You are right, Teacher; you have truly said that “he is one, and besides him there is no other”; 33 and “to love him with all the heart, and with all the understanding, and with all the strength”, and “to love one’s neighbour as oneself”, — this is much more important than all whole burnt-offerings and sacrifices.’ 34 When Jesus saw that he answered wisely, he said to him, ‘You are not far from the kingdom of God.’ After that no one dared to ask him any question.

The glass doors at the main entrance of the church mean that on a Sunday morning the church is looking out onto Lichfield, and Lichfield is looking into the church at worship (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (31 October 2021) invites us to pray:

Heavenly Father,

may we love you with all of our hearts, souls and minds.

Let us love each other

and all of creation

Lichfield Methodist Church was designed in the Victorian Gothic ornamental style by Thomas Guest of Birmingham (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

The former Regal Cinema, facing Lichfield Methodist Church at the corner of Tamworth Street and Lombard Street … now converted into apartments (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

Today is the Fourth Sunday before Advent (31 October 2021), but is being marked in this group of parishes as All Saints’ Sunday. I am presiding and preaching at the Parish Eucharist at 11 a.m. in Saint Mary’s Church, Askeaton, a united service for the Rathkeale and Kilnaughtin Group of Parishes, and later in the afternoon I am taking part in the farewell service for Bishop Kenneth Kearon in Saint Mary’s Cathedral, Limerick.

Before the day gets busy, I am taking a little time this morning for prayer, reflection and reading. Each morning in the time in the Church Calendar known as Ordinary Time, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, photographs of a church or place of worship;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

My theme last week was churches in Lichfield, and this week’s theme is Methodist churches. These two themes are linked this morning (31 October 2021) with my choice of Lichfield Methodist Church on Tamworth Street, Lichfield.

The Wesleyan Methodist Church on Tamworth Street, Lichfield, at its opening in 1892

The Methodist church at the city end of Tamworth Street, at the junction with Lombard Street, has undergone extensive redevelopment in recent years, with the addition of schoolrooms and meeting rooms. This is the home church of the Tamworth and Lichfield Circuit, which includes the Methodist churches in Lichfield, Alrewas Glascote, Shenstone and Tamworth.

Although John Wesley visited Lichfield three times in 1755, 1756 and 1777, he never preached in Lichfield, and the first Methodist chapel in Lichfield was not registered until 1811.

A warehouse at Gallows Wharf was registered in 1811 as places of worship by Joshua Kidger. A chapel was built in Lombard Street in 1813, and was opened in 1814 by Dr Adam Clarke in 1814.

There is evidence of another Wesleyan chapel that opened in 1815 and that in Wade Street in 1815 and that was still in use as late as 1837. During the 1851 Religious Census, the chapel in Lombard Street recorded attendances of 22 in the morning and 41 in the evening, but referred to congregations of 130 in the winter months.

Lichfield was in the Burton upon Trent Circuit until 1886, when the Tamworth and Lichfield Circuit was formed.

A site for a new chapel was bought in 1891. The ‘new’ Lichfield Wesleyan Methodist Church on Tamworth Street was built in the Victorian Gothic ornamental style to designs by Thomas Guest of Birmingham.

The foundation stones were laid on 12 August 1891 by Samuel Haynes, Mayor of Lichfield, and Reginald Stanley (1838-1914) of Nuneaton, a prominent Methodist business figure who owned brickyards, collieries, and an engineering firm. The builder was Edward Williams of Tamworth. The stone-laying ceremony was followed by a tea in the Guildhall.

The church was opened on 20 April 1892 by the President of the Methodist Conference, the Revd Dr Thomas Bowman Stephenson (1839-1912), regarded as ‘the architect of a more socially-minded Methodism’.

This new church replaced the Lombard Street chapel, but that building was not sold until 1921, after Tamworth House next to the new chapel was bought. New Sunday School premises were opened in 1924 and a period of growth led to extensions of the premises in 1972.

Meanwhile, there were Primitive Methodists in Lichfield from 1820 at Greenhill. They registered a schoolroom in Saint Mary’s parish for worship in 1831 and opened their own chapel in George Lane in 1847/1848. The George Lane chapel closed and was sold in 1934, when the members joined the Wesleyan Methodists at Tamworth Street.

In 1826, the Methodist New Connexion registered a barn in Sandford Street that had formerly been used by the Congregationalists. It was replaced in 1833 by a chapel in Queen Street, but this was sold in 1859 when the congregation disbanded.

Major alterations were made to the church on Tamworth Street in 1982, when the sanctuary was relocated at the Tamworth Street end and with new entrance facing Tamworth House. The pews were replaced by chairs from a prison on the Isle of Wight prison. But the loss of the choir stalls also led to the demise of the choir itself.

Meanwhile, a growth in population in Lichfield in this period, particularly with the development of the Boley Park estate, was matched by a growing membership, which reached 348 in 1987.

The church buildings were refurbished in 1998-1999 and again in 2012. The glass doors at the main entrance of the church mean that on a Sunday morning the church is looking out onto Lichfield, and Lichfield is looking into the church at worship … an architecturally perfect way to express the mission of the Church.

The Minister of Lichfield Methodist Church is the Revd Roger Baker, Superintendent of the Tamworth and Lichfield Methodist Circuit, and Sunday services are at 10 a.m.

The foundation stone was laid on 12 August 1891 by Samuel Haynes, Mayor of Lichfield (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

Mark 12: 28-34 (NRSVA):

28 One of the scribes came near and heard them disputing with one another, and seeing that he answered them well, he asked him, ‘Which commandment is the first of all?’ 29 Jesus answered, ‘The first is, “Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is one; 30 you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength.” 31 The second is this, “You shall love your neighbour as yourself.” There is no other commandment greater than these.’ 32 Then the scribe said to him, ‘You are right, Teacher; you have truly said that “he is one, and besides him there is no other”; 33 and “to love him with all the heart, and with all the understanding, and with all the strength”, and “to love one’s neighbour as oneself”, — this is much more important than all whole burnt-offerings and sacrifices.’ 34 When Jesus saw that he answered wisely, he said to him, ‘You are not far from the kingdom of God.’ After that no one dared to ask him any question.

The glass doors at the main entrance of the church mean that on a Sunday morning the church is looking out onto Lichfield, and Lichfield is looking into the church at worship (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (31 October 2021) invites us to pray:

Heavenly Father,

may we love you with all of our hearts, souls and minds.

Let us love each other

and all of creation

Lichfield Methodist Church was designed in the Victorian Gothic ornamental style by Thomas Guest of Birmingham (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

The former Regal Cinema, facing Lichfield Methodist Church at the corner of Tamworth Street and Lombard Street … now converted into apartments (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

30 October 2021

First Belonging –

from Sarawak to England and Back

With Charlotte Hunter during a recent visit to Dublin

Patrick Comerford

Some years ago, I wrote a paper for the journal Ruach on belonging in time and space, through family and place. Using words from John Betjeman, ‘To praise eternity in time and place,’ I discussed my own search for ‘a spirituality of place’ (‘To praise eternity in time and place … searching for a spirituality of place’ Ruach, No 4 (Michaelmas 2017), pp 50-56).

I maintain a family history website that connects me with people across the globe who share my surname and its variants, including Comerford, Commerford and Comberford. This website allows many people to develop a shared identity, not only because of a shared family name, but because they believe that they have found an identity that is rooted in time and place.

Many of us feel rootless, both in time and place. We do not know where we are because we do not know where we have come from, and so question where we are going. Despite shared cultures, that have many similar and familiar expressions, identity with place is a feeling that varies from one country to the next.

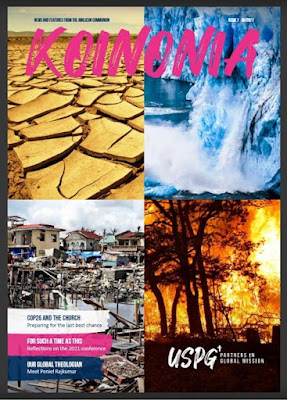

So, it was with particular personal interest that I read a feature on place and belonging that I could identify with by my dear friend Charlotte Hunter in the current edition of Koinonia (Issue 7, 10/2021, p 22), the magazine of the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel):

First Belonging – from Sarawak to England and Back

Charlotte Hunter writes of her time on USPG’s Journey with Us programme

Having been accepted on ‘Journey with Us’ in November 2015, my 12-month placement was with the Anglican Diocese of Kuching in Malaysia. It was no coincidence that I ended up in my mother’s original city. This gave me the chance to connect with the Anglican church and with my family history on a deeper level. Since then, I have chosen to stay in Kuching for several months every year, still in the neighbourhood of my mother’s birth.

My claim to being a member of the Kuching community may seem tenuous. Though a daughter of a Sarawakian-Chinese mother, I am also a product of a Northern Irish father. Though there were extended visits to Kuching as a child I was born and raised in England, and English is my mother tongue. However, in Kuching there exists for me a physical rootedness to my identity in the form of a traditional style shophouse on Carpenter Street, in the heart of the old town, from which my maternal family flows.

You may ask why this is important to me, and the answer may be that because my identity is split along the fault lines of race, culture, and continents, I’ve always felt a need for something physical, something definitive, to help me see in part who I am. This extends to the bricks and mortar of the house in which my mother was born, to the portrait of my late uncle – hung now with the photos of his parents – to my cousin at work in the family trade of watch repair, bent over his microscope as his father had done before him, and our grandfather before him, and our great grandfather before him … ‘The poetry of the everyday’, I believe it’s called.

There’s a continuity present that stretches outwards to the rest of our quarter, in particular to the thin triangle formed between the family shophouse, the temple, and Lau Ya Keng food court. The food court has been a daily part of family life reaching back to my mother's childhood, and during those extended visits, part of mine too. I now feel a deep-seated recognition of the smell of kerosene from the mobile cookers mingled with freshly brewed coffee, while the sound of torrential rain pounds on corrugated metal roofs. It was in here that my uncle and I last spoke before his final illness, where he whispered to me in his failing voice: ‘I used to bring you here for satay when you were a little girl, and now you are bringing me’.

One cousin tells me I have a tendency to romanticise life in these parts, and I fear she is right. After all, for all the familiarity there is the unfamiliarity – what the writer Amin Maalouf describes as ‘being estranged from the very traditions to which I belong’. I think about the metal grille across the front of the shophouse which, when the shop is closed, needs to be pulled back to let anyone in or out. I have never been able to manage it.

Not because it is heavy or stuck, but like a mortice key in a tricky lock, it takes a sleight of hand gained through habitude to make it shift – something I do not possess. On more pensive, introspective days, it becomes a symbol for the alienation I know exists between myself and this society in which I both belong, and cannot one hundred percent belong. I speak none of the local languages, without which no person can ever truly inhabit a society, and for all my extended childhood visits, ultimately, I was socialised in England. The consequence is that there are social and cultural complexities within both my family and the wider community which I might never understand.

Nonetheless, the feeling of belonging is stronger than any sense of non-belonging. Were anyone to ask me where my first point of identity lies, I would say right here, among these narrow streets and dark, dilapidated shophouses, in the chaos and in the heat. I would say I belong to one house in particular – the place where I’ve found the steadfastness I’ve always needed, the wellspring where four generations of my family have lived, worked, married, been born, and died. When the time comes, throw my ashes in the back yard. I’ll be home.

This is an edited version of an article first written for KINO magazine, published March 2020.

Patrick Comerford

Some years ago, I wrote a paper for the journal Ruach on belonging in time and space, through family and place. Using words from John Betjeman, ‘To praise eternity in time and place,’ I discussed my own search for ‘a spirituality of place’ (‘To praise eternity in time and place … searching for a spirituality of place’ Ruach, No 4 (Michaelmas 2017), pp 50-56).

I maintain a family history website that connects me with people across the globe who share my surname and its variants, including Comerford, Commerford and Comberford. This website allows many people to develop a shared identity, not only because of a shared family name, but because they believe that they have found an identity that is rooted in time and place.

Many of us feel rootless, both in time and place. We do not know where we are because we do not know where we have come from, and so question where we are going. Despite shared cultures, that have many similar and familiar expressions, identity with place is a feeling that varies from one country to the next.

So, it was with particular personal interest that I read a feature on place and belonging that I could identify with by my dear friend Charlotte Hunter in the current edition of Koinonia (Issue 7, 10/2021, p 22), the magazine of the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel):

First Belonging – from Sarawak to England and Back

Charlotte Hunter writes of her time on USPG’s Journey with Us programme

Having been accepted on ‘Journey with Us’ in November 2015, my 12-month placement was with the Anglican Diocese of Kuching in Malaysia. It was no coincidence that I ended up in my mother’s original city. This gave me the chance to connect with the Anglican church and with my family history on a deeper level. Since then, I have chosen to stay in Kuching for several months every year, still in the neighbourhood of my mother’s birth.

My claim to being a member of the Kuching community may seem tenuous. Though a daughter of a Sarawakian-Chinese mother, I am also a product of a Northern Irish father. Though there were extended visits to Kuching as a child I was born and raised in England, and English is my mother tongue. However, in Kuching there exists for me a physical rootedness to my identity in the form of a traditional style shophouse on Carpenter Street, in the heart of the old town, from which my maternal family flows.

You may ask why this is important to me, and the answer may be that because my identity is split along the fault lines of race, culture, and continents, I’ve always felt a need for something physical, something definitive, to help me see in part who I am. This extends to the bricks and mortar of the house in which my mother was born, to the portrait of my late uncle – hung now with the photos of his parents – to my cousin at work in the family trade of watch repair, bent over his microscope as his father had done before him, and our grandfather before him, and our great grandfather before him … ‘The poetry of the everyday’, I believe it’s called.

There’s a continuity present that stretches outwards to the rest of our quarter, in particular to the thin triangle formed between the family shophouse, the temple, and Lau Ya Keng food court. The food court has been a daily part of family life reaching back to my mother's childhood, and during those extended visits, part of mine too. I now feel a deep-seated recognition of the smell of kerosene from the mobile cookers mingled with freshly brewed coffee, while the sound of torrential rain pounds on corrugated metal roofs. It was in here that my uncle and I last spoke before his final illness, where he whispered to me in his failing voice: ‘I used to bring you here for satay when you were a little girl, and now you are bringing me’.

One cousin tells me I have a tendency to romanticise life in these parts, and I fear she is right. After all, for all the familiarity there is the unfamiliarity – what the writer Amin Maalouf describes as ‘being estranged from the very traditions to which I belong’. I think about the metal grille across the front of the shophouse which, when the shop is closed, needs to be pulled back to let anyone in or out. I have never been able to manage it.

Not because it is heavy or stuck, but like a mortice key in a tricky lock, it takes a sleight of hand gained through habitude to make it shift – something I do not possess. On more pensive, introspective days, it becomes a symbol for the alienation I know exists between myself and this society in which I both belong, and cannot one hundred percent belong. I speak none of the local languages, without which no person can ever truly inhabit a society, and for all my extended childhood visits, ultimately, I was socialised in England. The consequence is that there are social and cultural complexities within both my family and the wider community which I might never understand.

Nonetheless, the feeling of belonging is stronger than any sense of non-belonging. Were anyone to ask me where my first point of identity lies, I would say right here, among these narrow streets and dark, dilapidated shophouses, in the chaos and in the heat. I would say I belong to one house in particular – the place where I’ve found the steadfastness I’ve always needed, the wellspring where four generations of my family have lived, worked, married, been born, and died. When the time comes, throw my ashes in the back yard. I’ll be home.

This is an edited version of an article first written for KINO magazine, published March 2020.

Praying in Ordinary Time 2021:

154, Saint John’s Church, Wall

Saint John’s Church, Wall, stands on the site of a Roman temple dedicated to the goddess Minerva (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

Before the day begins, I am taking a little time this morning for prayer, reflection and reading. Each morning in the time in the Church Calendar known as Ordinary Time, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, photographs of a church or place of worship;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

My theme for this week is churches in Lichfield, where I spent part of the week before last in a retreat of sorts, following the daily cycle of prayer in Lichfield and visiting the chapel in Saint John’s Hospital and other churches.

In this series, I have already visited Lichfield Cathedral (15 March), Holy Cross Church (26 March), the chapel in Saint John’s Hospital (14 March), the Church of Saint Mary and Saint George, Comberford (11 April), Saint Bartholomew’s Church, Farewell (2 September) and the former Franciscan Friary in Lichfield (12 October).

This week’s theme of Lichfield churches, which I began with Saint Chad’s Church on Sunday, included Saint Mary’s Church on Monday, Saint Michael’s Church on Tuesday, Christ Church, Leomansley, on Wednesday, Wade Street Church on Thursday, and the chapel of Dr Milley’s Hospital yesterday.

This theme continues this morning (30 October 2021) with Saint John’s Church, Wall.

Saint John’s Church, Wall, was designed by WB Moffatt and Sir Gilbert Scott (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Wall is a small village just south of Lichfield, close to the A5 and the junction of the Roman roads Watling Street and Rynkild Street. Today, it is best known for the ruins of the Roman settlement at Letocetum, although it is not as well-visited as other Roman ruins throughout England.

In the first century AD, A fort was built in the upper area of the village near to the present church in 50s or 60s and Watling Street was built to the south in the 70s. By the second century, the settlement covered about 30 acres west of the later Wall Lane.

In the late third or early fourth century, the eastern part of the settlement of approximately six acres, between the present Wall Lane and Green Lane and straddling Watling Street, was enclosed with a stone wall surrounded by an earth rampart and ditches. Civilians continued to live inside the settlement and on its outskirts in the late fourth century.

The settlement declined rapidly soon after the Romans left Britain in AD 410 and the focus of settlement shifted to Lichfield. After the Romans left, Wall never developed beyond a small village.

The earliest mediaeval settlement may have been on the higher ground around Wall. Close to the church, Wall House on Green Lane probably stands on the site of the mediaeval manor house, while Wall Hall stands on the site of a 17th century house. The Trooper Inn was in business by 1851. In the 1950s, 10 council houses were built on a road called The Butts. The re-routing of the A5 around Wall, as the Wall by-pass in 1965, relieved the village of traffic, re-establishing its quiet nature.

The parish church in Wall was built in 1837 and was consecrated as the Parish Church of Saint John in 1843. The church is set at the top of a rise and is said to stand on the site of a Roman temple dedicated to the goddess Minerva, and later used for Mithraic worship. But even before the Romans, this may have been the site of Celtic temple dedicated to the god Cernunnos, who was the equivalent of the Roman Pan.

The site for the church was donated by John Mott of Wall House in 1840, along with an endowment of £700, and a further grant of £500 came from Robert Hill, a previous owner of Wall House.

The church is the work of William Bonython Moffatt (1812-1887) and his partner, the great Victorian architect Sir Gilbert Scott (1811-1878).

The church is built of pale yellow, chisel finished sandstone. There are tiled roofs on corbelled eaves with verge parapets. The church has a west steeple, nave and chancel. The steeple is a square tower of approximately three stages on a plinth with two-stage diagonal buttresses, and is chamfered in at the last stage to form an octagonal base for the short spire.

There is a single stage of small lucarnes and a small slit trefoil-headed window over the pointed west door.

The nave is of four bays on a plinth and is divided by two stage buttresses. There are two-light, square-headed trefoil-light windows to each bay.

The chancel is lower than the nave but has similar details and consists of one short bay. At the east end, there is a three-light, labelled pointed, Perpendicular-style window with panel tracery.

The interior is plain-finished, with a plastered nave, a single hammer beam and arch braced roof with double purlins and exposed rafters. There is a narrow, pointed chancel arch.

The church was built as a district chapel for the Parish of Saint Michael in Lichfield, and the finished chapel was consecrated by the Bishop of Hereford in May 1843 on behalf of the Bishop of Lichfield.

Charles Eamer Kempe (1837-1907), the Victorian stained glass designer and manufacturer, and his studios produced over 4,000 windows along with designs for altars and altar frontals, furniture and furnishings, lichgates and memorials that helped to define a later 19th century Anglican style. Many of Kempe’s works can be seen in Lichfield Cathedral, Christ Church, Lichfield, and the Chapel of Saint John’s Hospital, Lichfield. He also designed the reredos in the Lady Chapel, Lichfield.

Kempe’s window in Saint John’s Church, Wall, shows the Risen Christ meeting Mary Magdalene in the Garden on the morning of the Resurrection, and addressing her: ‘Mary.’ Peter and John who arrived at the empty tomb that Easter morning can be seen as two small figures in the background.

The dedication on the window reads: ‘To the glory of God and in loving memory of Georgina Charlotte Harrison, AD MCMIX (1909).’

South Side:

The windows on the south side, beginning at the west end, beside the entrance, depict:

1, Saint John the Baptist and the Prophet Isaiah: Both Saint John the Baptist and the Prophet Isaiah, who herald the promised coming of Christ as the Son of Man, are depicted holding staffs. The dedication reads: ‘To the glory of God & as a thank offering this window has been erected by HS and CAS.’

2, The Risen Christ meets Mary Magdalene.

3, Saint John the Divine and Saint Luke: This window may also be the work of CE Kempe. The left light shows Saint John the Evangelist holding a parchment with the opening verse of his Gospel: ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the word was with God, and the word was God.’ The window’s dedication reads: ‘To the glory of God and in loving memory of Anne Bradburne AD 1899.’

4, Saint Peter and Saint Paul: Saint Peter is on the left holding the keys of the kingdom, while his stole is inscribed with the Greek word Άγιος (‘Holy,’ ‘Saint’ or ‘Saintly’). Saint Paul, on the right, is holding a sword, the symbol of his martyrdom. The dedication reads: ‘To the Glory of God & in loving memory of the Rev W Williams, formerly vicar of this parish.’ The Revd William Williams was the Vicar of Wall for 12 years from 1864 to 1876.

The East End window:

The East Window above the altar shows Christ as the Good Shepherd. There are three sets of initials in the top of the window: Alpha (Α) and Omega (Ω), the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet, and a title of Christ in the Book of Revelation; IHS, representing the name Jesus, spelt ΙΗΣΟΥΣ in Greek capitals (Ιησουσ); and the Chi Rho symbol (XP), representing the Greek word ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ (Χριστός, Christ). On either side of Christ are the Virgin Mary (left) and Saint John the Divine (right).

The North Side:

The windows on the north side, from left to right, beginning at the west end or entrance, depict:

1, Abel and Enoch: The first window on the north side shows Abel and Enoch. Abel on the left is holding a lamb, while Enoch is one of the early prophets. The Letter to the Hebrews praises the faith of Abel and Enoch (see Hebrew 11: 4-6). The dedication reads: ‘To the glory of God & in memory of Ann Danks of Fosseway in this parish, died Sep 3 1877.’

2, Noah and Abraham: Noah (left) is holding the ark in his arms, while Abraham is holding a rather unwieldy knife representing his intended sacrifice of Isaac. This window is without any dedication or inscription.

3, Moses and Elias: This window, with Moses on the left and Elijah (or Elias) on the right has the dedication: ‘To the glory of God and in loving memory of Louisa Ann Mott & Henrietta Ley.’ Moses and Elijah represent the Law and the Prophets, and at the Transfiguration they are seen on either side of Christ.

The West End:

The two, single-light windows at the west end, at either side of the entrance, depict the Lamb of God (north) and the Holy Spirit (south).

The Church of Saint John the Baptist is at Green Lane, Wall, Staffordshire, WS14 0AS. It is uited with the Parish of Saint Michael, Greenhill. The Sunday services are normally at 10 a.m. each week. The benefice is awaiting a new rector, but in the past Sunday services have included Holy Communion on the first, second and fourth Sundays, Morning Worship on the third Sunday, and ‘Wall praise’ on the fifth Sunday, described as ‘a serviced for all the family.’

The East Window in Saint John’s Church, Wall, depicts Christ as the Good Shepherd (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Luke 14: 1, 7-11 (NRSVA):

1 On one occasion when Jesus was going to the house of a leader of the Pharisees to eat a meal on the sabbath, they were watching him closely.

7 When he noticed how the guests chose the places of honour, he told them a parable. 8 ‘When you are invited by someone to a wedding banquet, do not sit down at the place of honour, in case someone more distinguished than you has been invited by your host; 9 and the host who invited both of you may come and say to you, “Give this person your place”, and then in disgrace you would start to take the lowest place. 10 But when you are invited, go and sit down at the lowest place, so that when your host comes, he may say to you, “Friend, move up higher”; then you will be honoured in the presence of all who sit at the table with you. 11 For all who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted.’

The Risen Christ meets Mary Magdalene … a window by CE Kempe in Saint John’s Church, Wall (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (30 October 2021) invites us to pray:

We pray for those who build bridges between those of different faiths and none, and for those with whom we share a common faith in Jesus as Lord. Give us unity of mind and spirit.

Saint John the Divine and Saint Luke … this window in Saint John’s Church, Wall, may also be the work of CE Kempe (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Looking down at the Roman site of Letocetum from the West Door of Saint John’s Church, Wall, south of Lichfield (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

Before the day begins, I am taking a little time this morning for prayer, reflection and reading. Each morning in the time in the Church Calendar known as Ordinary Time, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, photographs of a church or place of worship;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

My theme for this week is churches in Lichfield, where I spent part of the week before last in a retreat of sorts, following the daily cycle of prayer in Lichfield and visiting the chapel in Saint John’s Hospital and other churches.

In this series, I have already visited Lichfield Cathedral (15 March), Holy Cross Church (26 March), the chapel in Saint John’s Hospital (14 March), the Church of Saint Mary and Saint George, Comberford (11 April), Saint Bartholomew’s Church, Farewell (2 September) and the former Franciscan Friary in Lichfield (12 October).

This week’s theme of Lichfield churches, which I began with Saint Chad’s Church on Sunday, included Saint Mary’s Church on Monday, Saint Michael’s Church on Tuesday, Christ Church, Leomansley, on Wednesday, Wade Street Church on Thursday, and the chapel of Dr Milley’s Hospital yesterday.

This theme continues this morning (30 October 2021) with Saint John’s Church, Wall.

Saint John’s Church, Wall, was designed by WB Moffatt and Sir Gilbert Scott (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Wall is a small village just south of Lichfield, close to the A5 and the junction of the Roman roads Watling Street and Rynkild Street. Today, it is best known for the ruins of the Roman settlement at Letocetum, although it is not as well-visited as other Roman ruins throughout England.

In the first century AD, A fort was built in the upper area of the village near to the present church in 50s or 60s and Watling Street was built to the south in the 70s. By the second century, the settlement covered about 30 acres west of the later Wall Lane.

In the late third or early fourth century, the eastern part of the settlement of approximately six acres, between the present Wall Lane and Green Lane and straddling Watling Street, was enclosed with a stone wall surrounded by an earth rampart and ditches. Civilians continued to live inside the settlement and on its outskirts in the late fourth century.

The settlement declined rapidly soon after the Romans left Britain in AD 410 and the focus of settlement shifted to Lichfield. After the Romans left, Wall never developed beyond a small village.

The earliest mediaeval settlement may have been on the higher ground around Wall. Close to the church, Wall House on Green Lane probably stands on the site of the mediaeval manor house, while Wall Hall stands on the site of a 17th century house. The Trooper Inn was in business by 1851. In the 1950s, 10 council houses were built on a road called The Butts. The re-routing of the A5 around Wall, as the Wall by-pass in 1965, relieved the village of traffic, re-establishing its quiet nature.

The parish church in Wall was built in 1837 and was consecrated as the Parish Church of Saint John in 1843. The church is set at the top of a rise and is said to stand on the site of a Roman temple dedicated to the goddess Minerva, and later used for Mithraic worship. But even before the Romans, this may have been the site of Celtic temple dedicated to the god Cernunnos, who was the equivalent of the Roman Pan.

The site for the church was donated by John Mott of Wall House in 1840, along with an endowment of £700, and a further grant of £500 came from Robert Hill, a previous owner of Wall House.

The church is the work of William Bonython Moffatt (1812-1887) and his partner, the great Victorian architect Sir Gilbert Scott (1811-1878).

The church is built of pale yellow, chisel finished sandstone. There are tiled roofs on corbelled eaves with verge parapets. The church has a west steeple, nave and chancel. The steeple is a square tower of approximately three stages on a plinth with two-stage diagonal buttresses, and is chamfered in at the last stage to form an octagonal base for the short spire.

There is a single stage of small lucarnes and a small slit trefoil-headed window over the pointed west door.

The nave is of four bays on a plinth and is divided by two stage buttresses. There are two-light, square-headed trefoil-light windows to each bay.

The chancel is lower than the nave but has similar details and consists of one short bay. At the east end, there is a three-light, labelled pointed, Perpendicular-style window with panel tracery.

The interior is plain-finished, with a plastered nave, a single hammer beam and arch braced roof with double purlins and exposed rafters. There is a narrow, pointed chancel arch.

The church was built as a district chapel for the Parish of Saint Michael in Lichfield, and the finished chapel was consecrated by the Bishop of Hereford in May 1843 on behalf of the Bishop of Lichfield.

Charles Eamer Kempe (1837-1907), the Victorian stained glass designer and manufacturer, and his studios produced over 4,000 windows along with designs for altars and altar frontals, furniture and furnishings, lichgates and memorials that helped to define a later 19th century Anglican style. Many of Kempe’s works can be seen in Lichfield Cathedral, Christ Church, Lichfield, and the Chapel of Saint John’s Hospital, Lichfield. He also designed the reredos in the Lady Chapel, Lichfield.

Kempe’s window in Saint John’s Church, Wall, shows the Risen Christ meeting Mary Magdalene in the Garden on the morning of the Resurrection, and addressing her: ‘Mary.’ Peter and John who arrived at the empty tomb that Easter morning can be seen as two small figures in the background.

The dedication on the window reads: ‘To the glory of God and in loving memory of Georgina Charlotte Harrison, AD MCMIX (1909).’

South Side:

The windows on the south side, beginning at the west end, beside the entrance, depict:

1, Saint John the Baptist and the Prophet Isaiah: Both Saint John the Baptist and the Prophet Isaiah, who herald the promised coming of Christ as the Son of Man, are depicted holding staffs. The dedication reads: ‘To the glory of God & as a thank offering this window has been erected by HS and CAS.’

2, The Risen Christ meets Mary Magdalene.

3, Saint John the Divine and Saint Luke: This window may also be the work of CE Kempe. The left light shows Saint John the Evangelist holding a parchment with the opening verse of his Gospel: ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the word was with God, and the word was God.’ The window’s dedication reads: ‘To the glory of God and in loving memory of Anne Bradburne AD 1899.’

4, Saint Peter and Saint Paul: Saint Peter is on the left holding the keys of the kingdom, while his stole is inscribed with the Greek word Άγιος (‘Holy,’ ‘Saint’ or ‘Saintly’). Saint Paul, on the right, is holding a sword, the symbol of his martyrdom. The dedication reads: ‘To the Glory of God & in loving memory of the Rev W Williams, formerly vicar of this parish.’ The Revd William Williams was the Vicar of Wall for 12 years from 1864 to 1876.

The East End window:

The East Window above the altar shows Christ as the Good Shepherd. There are three sets of initials in the top of the window: Alpha (Α) and Omega (Ω), the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet, and a title of Christ in the Book of Revelation; IHS, representing the name Jesus, spelt ΙΗΣΟΥΣ in Greek capitals (Ιησουσ); and the Chi Rho symbol (XP), representing the Greek word ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ (Χριστός, Christ). On either side of Christ are the Virgin Mary (left) and Saint John the Divine (right).

The North Side:

The windows on the north side, from left to right, beginning at the west end or entrance, depict:

1, Abel and Enoch: The first window on the north side shows Abel and Enoch. Abel on the left is holding a lamb, while Enoch is one of the early prophets. The Letter to the Hebrews praises the faith of Abel and Enoch (see Hebrew 11: 4-6). The dedication reads: ‘To the glory of God & in memory of Ann Danks of Fosseway in this parish, died Sep 3 1877.’

2, Noah and Abraham: Noah (left) is holding the ark in his arms, while Abraham is holding a rather unwieldy knife representing his intended sacrifice of Isaac. This window is without any dedication or inscription.

3, Moses and Elias: This window, with Moses on the left and Elijah (or Elias) on the right has the dedication: ‘To the glory of God and in loving memory of Louisa Ann Mott & Henrietta Ley.’ Moses and Elijah represent the Law and the Prophets, and at the Transfiguration they are seen on either side of Christ.

The West End:

The two, single-light windows at the west end, at either side of the entrance, depict the Lamb of God (north) and the Holy Spirit (south).

The Church of Saint John the Baptist is at Green Lane, Wall, Staffordshire, WS14 0AS. It is uited with the Parish of Saint Michael, Greenhill. The Sunday services are normally at 10 a.m. each week. The benefice is awaiting a new rector, but in the past Sunday services have included Holy Communion on the first, second and fourth Sundays, Morning Worship on the third Sunday, and ‘Wall praise’ on the fifth Sunday, described as ‘a serviced for all the family.’

The East Window in Saint John’s Church, Wall, depicts Christ as the Good Shepherd (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Luke 14: 1, 7-11 (NRSVA):

1 On one occasion when Jesus was going to the house of a leader of the Pharisees to eat a meal on the sabbath, they were watching him closely.

7 When he noticed how the guests chose the places of honour, he told them a parable. 8 ‘When you are invited by someone to a wedding banquet, do not sit down at the place of honour, in case someone more distinguished than you has been invited by your host; 9 and the host who invited both of you may come and say to you, “Give this person your place”, and then in disgrace you would start to take the lowest place. 10 But when you are invited, go and sit down at the lowest place, so that when your host comes, he may say to you, “Friend, move up higher”; then you will be honoured in the presence of all who sit at the table with you. 11 For all who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted.’

The Risen Christ meets Mary Magdalene … a window by CE Kempe in Saint John’s Church, Wall (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (30 October 2021) invites us to pray:

We pray for those who build bridges between those of different faiths and none, and for those with whom we share a common faith in Jesus as Lord. Give us unity of mind and spirit.

Saint John the Divine and Saint Luke … this window in Saint John’s Church, Wall, may also be the work of CE Kempe (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Looking down at the Roman site of Letocetum from the West Door of Saint John’s Church, Wall, south of Lichfield (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

29 October 2021

Heritage award for film

recalling ‘Memories of

a Cork Jewish Childhood’

The former Cork Synagogue at 10 South Terrace (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

For my Friday evening reflections this evening, I am watching once again Memories of a Cork Jewish Childhood, produced by Ruti Lachs.

I have returned to this short film because it was one of the runners-up in the National Heritage Week Awards ceremony last week, and it received a special mention.

In this film, former Cork residents remember their childhoods in Ireland: their Jewish upbringing, the synagogue, the characters, the sea. Interspersed with photos from the last hundred years of life in Jewish Cork, these stories paint a picture of a time and community gone by.

It is interesting to hear members of some old Cork Jewish families speaking so fondly of life in Cork. Some, despite years of living outside of Cork, are still proud of their Cork accents.

The film is a follow-up to Ruti’s 2020 Cork Jewish Culture Virtual Walk video and webpage which also won a National Heritage Day Award. It is interspersed with photographs from the last 100 years of life in Jewish Cork, and these stories paint a picture of a time and community gone by. This can be seen on www.rutilachs.ie.

Since its release two months ago (14 August 2021), Memories of a Cork Jewish Childhood has been available to view on the Cork Heritage Open Day and Heritage Week websites as well: https://www.corkcity.ie/en/cork-heritage-open-day/ and https://www.heritageweek.ie.

This project was made possible by Cork City Council and the Heritage Plan.

A traditional Jewish blessing on children on Sabbath evenings or FRiday evenings draws on the words of the priestly blessing (see Numbers 6: 24-26) prays:

(For boys):

May you be like Ephraim and Menashe.

(For girls):

May you be like Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah.

For both boys and girls:

May God bless you and protect you.

May God show you favour and be gracious to you.

May God show you kindness and grant you peace

The blessing is performed differently in every family. In some traditional homes, only the father blesses the children. In other families, both parents give blessings – either together and in unison, or first one parent, followed by the other. In some homes, the mother blesses the girls and the father blesses the boys.

Usually the person giving the blessing places one or both hands on the child’s head. Some parents bless each child in succession, working from oldest to youngest. Others bless all of the girls together, and all of the boys together.

After the blessing, some parents take a moment to whisper something to their child – praising him or her for something he or she did during the week, or conveying some extra encouragement and love.

Almost every family concludes the blessing with a kiss or a hug.

Shabbat Shalom

Patrick Comerford

For my Friday evening reflections this evening, I am watching once again Memories of a Cork Jewish Childhood, produced by Ruti Lachs.

I have returned to this short film because it was one of the runners-up in the National Heritage Week Awards ceremony last week, and it received a special mention.

In this film, former Cork residents remember their childhoods in Ireland: their Jewish upbringing, the synagogue, the characters, the sea. Interspersed with photos from the last hundred years of life in Jewish Cork, these stories paint a picture of a time and community gone by.

It is interesting to hear members of some old Cork Jewish families speaking so fondly of life in Cork. Some, despite years of living outside of Cork, are still proud of their Cork accents.

The film is a follow-up to Ruti’s 2020 Cork Jewish Culture Virtual Walk video and webpage which also won a National Heritage Day Award. It is interspersed with photographs from the last 100 years of life in Jewish Cork, and these stories paint a picture of a time and community gone by. This can be seen on www.rutilachs.ie.

Since its release two months ago (14 August 2021), Memories of a Cork Jewish Childhood has been available to view on the Cork Heritage Open Day and Heritage Week websites as well: https://www.corkcity.ie/en/cork-heritage-open-day/ and https://www.heritageweek.ie.

This project was made possible by Cork City Council and the Heritage Plan.

A traditional Jewish blessing on children on Sabbath evenings or FRiday evenings draws on the words of the priestly blessing (see Numbers 6: 24-26) prays:

(For boys):

May you be like Ephraim and Menashe.

(For girls):

May you be like Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah.

For both boys and girls:

May God bless you and protect you.

May God show you favour and be gracious to you.

May God show you kindness and grant you peace

The blessing is performed differently in every family. In some traditional homes, only the father blesses the children. In other families, both parents give blessings – either together and in unison, or first one parent, followed by the other. In some homes, the mother blesses the girls and the father blesses the boys.

Usually the person giving the blessing places one or both hands on the child’s head. Some parents bless each child in succession, working from oldest to youngest. Others bless all of the girls together, and all of the boys together.

After the blessing, some parents take a moment to whisper something to their child – praising him or her for something he or she did during the week, or conveying some extra encouragement and love.

Almost every family concludes the blessing with a kiss or a hug.

Shabbat Shalom

Praying in Ordinary Time 2021:

153, the Chapel of Dr Milley’s Hospital

Dr Milley’s Hospital on Beacon Street, Lichfield … refounded and endowed by Canon Thomas Milley almost 520 years ago in 1504; the chapel is immediately above the entrance (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

Patrick Comerford

Before the day begins, I am taking a little time this morning for prayer, reflection and reading. Each morning in the time in the Church Calendar known as Ordinary Time, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, photographs of a church or place of worship;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

My theme for this week is churches in Lichfield, where I spent part of the week before last in a retreat of sorts, following the daily cycle of prayer in Lichfield and visiting the chapel in Saint John’s Hospital and other churches.