New Street Station, Birmingham, was built on the site of a synagogue established in the 1780s in the Froggery district (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2023)

Patrick Comerford

I spent much of the day yesterday on my own self-guided walking tour of Jewish Birmingham, including Britain’s oldest active ‘cathedral synagogue.’

There are few records if any of a Jewish presence in mediaeval Birmingham, which was only a market town until the Industrial Revolution, and there has never been a large Jewish community in Birmingham.

Jews began to have a numerical presence in Birmingham in the early days of the Industrial Revolution. Smaller Jewish communities later developed in other parts of the Midlands in the Victorian period, including Wolverhampton, the Five Towns of ‘The Potteries’ in Staffordshire, Coventry, Nottingham and Northampton.

The first Jews to settle in noticeable numbers in Birmingham arrived ca 1730. A generation later, Meyer Oppenheim built the city’s first glass kiln. A synagogue was established in the 1780s in the Froggery district, a low-lying marshy and swampy area that was later built over with Station Road and New Street Station in 1845.

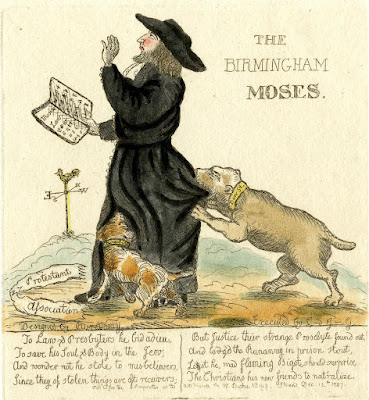

Seven years after the anti-Catholic ‘Gordon Riots’ in 1780, Lord George Gordon (1751-1793) converted to Judaism in Birmingham in 1787, at the age of 36. Some sources say his conversion occurred earlier when he was in exile in Holland. However, it seems he underwent brit milah or ritual circumcision at the synagogue in Severn Street in 1787, when he took the name of Yisrael bar Avraham Gordon, and became a Ger Tsedek or righteous convert.

Gordon lived with a Jewish woman in the Froggery, grew ‘a beard of extraordinary length,’ dressed like a Jew, and observed kosher dietary standards. However, little else is known about his life as a Jew in Birmingham until he was arrested and jailed in 1788.

Gordon lived as an Orthodox Jew In Newgate Prison, where he put on his tzitzit and tefillin daily, fasted on the days of fasting, and celebrated the Jewish holidays. The prison authorities supplied him with kosher meat, wine and Shabbat challos, and they allowed him to have a minyan on the Sabbath, to affix a mezuza on his cell door, and to hang the Ten Commandments on the wall. In Barnaby Rudge, Charles Dickens describes Gordon as a true tzadik or pious man among the prisoners.

When Gordon’s prison sentence was due to end, he appeared in court on 28 January 1793, and refused to remove his hat. He died of typhoid fever in Newgate Prison on 1 November 1793 at the age of 41. He was buried not in a Jewish cemetery but in the detached burial ground of Saint James’s Church, Piccadilly. It later became Saint James’s Gardens, but in recent years the burials there were reinterred to make way for work on HS2.

A new synagogue was built in Hurst Street, Birmingham, in the vicinity of the Froggery, in 1809. But it was destroyed, along with other places of worship during riots in 1813. It was rebuilt and enlarged in Greek Revival style in 1823-1827 by the architect Richard Tutin.

Because of the growth in the Industrial Revolution in the 1830s, cities in the Midlands and the north, such as Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool, attracted many people from other parts of England and other countries, including Jewish immigrants.

Many of these new arrivals included Jewish immigrants from Germany, the Netherlands and Poland. By 1851, there were 780 Jews in Birmingham, of whom about a quarter were recent arrivals from Poland and Russia. They were active mainly in four areas of economic life: glaziers, slipper makers, tailors and traders. These patterns of migration and growth mean that the surviving Jewish heritage in Birmingham is largely Victorian.

The synagogue on Hurst Street was refurbished in 1851. However, a schism divided the community the following year (1852), leading to the formation of a rival synagogue on Wrottesley Street in 1853.

Unity was restored in 1855, and the two congregations united at the opening of the new synagogue on Singers Hill in 1856. The synagogue on Hurst Street was sold to the Freemasons that year and became the Athol Masonic Hall.

The Birmingham Hebrew Congregation, usually known as Singers Hill Synagogue, was founded in 1856 and was built on Blucher Street and Ellis Street. It is often known as the ‘Cathedral Synagogue’.

On the eve of World War I, there were 6,000 Jews in Birmingham, and the community reached a peak of 6,600 in 1918.

There were still 6,300 Jews living in Birmingham in 1967. But, while Birmingham is England’s second city, it had a proportionately small Jewish community, depleted by the exodus to the suburbs and surrounding towns. The Solihull and District Hebrew Congregation was founded in 1963. Later, the Central Synagogue moved to Pershore Road, the New Synagogue moved to Park Road, and the Progressive Synagogue moved to Sheepecote Street.

More Jews left Birmingham in the 1980s, mainly for London, Manchester and Israel. There were then only 3,000 Jews in Birmingham in the 1980s, and census figures show about 2,200 Jews are living in Birmingham today.

In my self-guided tour of Jewish Birmingham this week, with the help of Sharman Kadish’s superb book, Jewish Heritage in Britain and Ireland: an architectural guide, I visited many of these Victorian landmarks. But more about them, hopefully, in the days or weeks to come.

The Birmingham Moses (1787), Lord George Gordon caricatured in a satirical print by William Dent

No comments:

Post a Comment