Patrick Comerford

The term Bible can refer to the Hebrew Bible, which corresponds to the Christian Old Testament, or the Christian Bible, which in addition to the Old Testament contains the New Testament.

Hellenistic Jews first used the Greek term τὰ βιβλία (ta biblia), ‘the books’, to describe their sacred books or texts.

The English word Bible is derived from Koinē Greek: τὰ βιβλία (ta biblia), meaning ‘the books’ (singular βιβλίον, biblion). The literal meaning of the word βιβλίον was ‘scroll’ and it came to be used as the ordinary word for book. It is the diminutive of βύβλος (Byblos), ‘Egyptian papyrus’, possibly from the name of the Phoenician seaport of Byblos (also known as Gebal) from which Egyptian papyrus was exported to Greece.

The Bible is not one book, however; rather, it is a collection or anthology of religious texts that were originally written in Hebrew, Aramaic and Koine Greek. The earliest collection contained the first five books of the Bible, called the Torah in Hebrew and the Pentateuch (‘five books’) in Greek. The second-oldest part is a collection of narrative histories and prophecies (the Nevi’im). The third collection, the Ketuvim, contains the Psalms, proverbs, and narrative histories.

But the word Bible is generally not used in Judaism and the Hebrew word Tanakh (תָּנָ״ךְ) is generally used for the Hebrew Bible, derived from the first letters of the three components in Hebrew: the Torah (‘Teaching’), the Nevi'im (‘Prophets’), and the Ketuvim (‘Writings’). The Masoretic Text is the mediaeval version of the Tanakh – written in Hebrew and Aramaic – that is considered the authoritative text of the Hebrew Bible by modern Rabbinic Judaism.

The earliest translation of the Tanakh into any language was made into Greek. The Septuagint is a Koine Greek translation of the Tanakh from the third and second centuries BCE, and it largely overlaps with the Hebrew Bible.

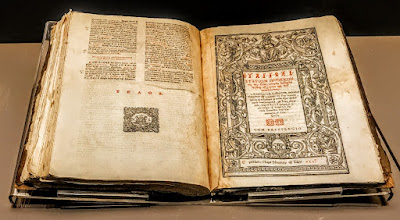

A Bible for liturgical use in a shop window in Rethymnon in Crete (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

After the conquests of Alexander the Great (336-323 BCE), Greek became the official language of Egypt, Syria and the eastern Mediterranean and the first translation of the Bible was into Greek. This was an initiative of the Jewish community of Alexandria in Egypt, and was made in different stages, lasting a few hundred years. An analysis of the language shows that the Torah was translated in the mid-third century BCE. After the Torah, the other sacred books were translated over the next two centuries.

This Greek translation has been known since antiquity as the Septuagint, from the Latin word septuaginta, meaning 70 (or in Hebrew Tirgum ha Shivʾim, the ‘Translation of the Seventy’). Tradition says 72 Jewish scholars (six scribes from each of the 12 tribes) were asked by Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285-247 BCE) to translate the Hebrew Bible into Greek to be added to the Library of Alexandria.

The scholars completed their task in 72 days. According to one account, they were kept in separate rooms but they all produced identical versions of the text, seen as a sign that their translation was inspired by God.

After the Septuagint translation of the Torah, other Hebrew Scriptures were translated into Greek, though exactly when and why remains uncertain. The historical, prophetic, and wisdom books were probably all translated during the second century BCE, in Egypt or in Palestine. So the Septuagint was a work in progress for a long time, and there is no one single, settled canon of the Hebrew Bible as translated by diaspora Jews and then reordered and used by Christians.

The oldest surviving manuscripts of the Septuagint include second century BCE fragments of Leviticus and Deuteronomy. Relatively-complete manuscripts of the Septuagint include the fourth century CE Codex Vaticanus and the fifth century Codex Alexandrinus. These are the oldest-surviving nearly-complete manuscripts of the Old Testament in any language.

By comparison, the oldest complete Hebrew texts date from the 10th century. The Leningrad Codex, the oldest complete version of the Hebrew Scriptures, dates to the 11th century, while the less complete Aleppo Codex dates from the 10th century.

Some peculiarities distinguish the Septuagint from the Hebrew canon. The Septuagint preserves older versions of parts of the Hebrew Scriptures, some going back long before the canon of the Hebrew Bible was finalised. Some books in the Septuagint are not in the Hebrew versions; when they do match, the order does not always coincide; and some books grouped apart in the Hebrew Bible are grouped together in the Septuagint.

The Septuagint made the Jewish scriptures available to the entire Greek-speaking world, a factor that determined it becoming the Old Testament version of the early Church. The first non-Jewish Christians used the Septuagint as since most of them could not read Hebrew. Common Greek or Koine Greek is the language of both the LXX and the New Testament. When the Gospels were written, and when Paul and the other New Testament writers were writing, they quoted the LXX, not the Hebrew Bible.

The adoption of the Greek Septuagint by the early Church was the main reason in its eventual rejection by the Jews. From then on, it was taken over by Christianity. The Septuagint text has since been the standard version of the Old Testament in the Greek Orthodox Church.

The Latin word septuaginta for the Greek Old Testament was first used by Josephus (ca 37-ca 100 CE), who writes about its formation in his Antiquities of the Jews. But Josephus trims the number of translators from 72 to 70, giving us the word Septuagint and its abbreviation LXX.

Saint John Chrysostom, the first writer to use the Greek phrase τὰ βιβλία (ta biblia, ‘the books’) to describe the Old and New Testaments together … a mid-18th century icon in the museum in Arkadi Monastery in Crete (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

The LXX was first compared with the Hebrew text of Scripture by Origen in third-century Alexandria, and then by Jerome, who retranslated the Christian Bible from Hebrew and Greek into Latin.

Saint John Chrysostom appears to be the first writer to use the Greek phrase τὰ βιβλία (ta biblia, ‘the books’) to describe both the Old and New Testaments together. He uses the phrase in his Homilies on Matthew, some time ca 386-388 CE.

The Latin biblia sacra (‘holy books’) translates the Greek τὰ βιβλία τὰ ἅγια (tà biblía tà hágia, ‘the holy books’). The mediaeval Latin biblia is short for biblia sacra ‘holy book’. It gradually came to be regarded as a feminine singular noun (

When fundamentalists of any persuasion claim they are Bible-believing, could they please explain which Bible they believe, and respond to the irony that the word Bible only emerges in the late fourth century and only comes into the English language through late mediaeval Latin – it is not a Biblical word at all.

Previous word: 52, ἰχθύς (ichthýs) and ψάρι (psari), fish.

Series to be continued

Browsers in a second-hand bookshop in Souliou Street, Rethymnon … the English word Bible is derived from the Koinē Greek τὰ βιβλία meaning ‘the books’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Previous words in this series:

1, Neologism, Νεολογισμός.

2, Welcoming the stranger, Φιλοξενία.

3, Bread, Ψωμί.

4, Wine, Οίνος and Κρασί.

5, Yogurt, Γιαούρτι.

6, Orthodoxy, Ορθοδοξία.

7, Sea, Θᾰ́λᾰσσᾰ.

8,Theology, Θεολογία.

9, Icon, Εἰκών.

10, Philosophy, Φιλοσοφία.

11, Chaos, Χάος.

12, Liturgy, Λειτουργία.

13, Greeks, Ἕλληνες or Ρωμαίοι.

14, Mañana, Αύριο.

15, Europe, Εὐρώπη.

16, Architecture, Αρχιτεκτονική.

17, The missing words.

18, Theatre, θέατρον, and Drama, Δρᾶμα.

19, Pharmacy, Φᾰρμᾰκείᾱ.

20, Rhapsody, Ραψῳδός.

21, Holocaust, Ολοκαύτωμα.

22, Hygiene, Υγιεινή.

23, Laconic, Λακωνικός.

24, Telephone, Τηλέφωνο.

25, Asthma, Ασθμα.

26, Synagogue, Συναγωγή.

27, Diaspora, Διασπορά.

28, School, Σχολείο.

29, Muse, Μούσα.

30, Monastery, Μοναστήρι.

31, Olympian, Ολύμπιος.

32, Hypocrite, Υποκριτής.

33, Genocide, Γενοκτονία.

34, Cinema, Κινημα.

35, autopsy and biopsy

36, Exodus, ἔξοδος

37, Bishop, ἐπίσκοπος

38, Socratic, Σωκρατικὸς

39, Odyssey, Ὀδύσσεια

40, Practice, πρᾶξις

41, Idiotic, Ιδιωτικός

42, Pentecost, Πεντηκοστή

43, Apostrophe, ἀποστροφή

44, catastrophe, καταστροφή

45, democracy, δημοκρατία

46, ‘Αρχή, beginning, Τέλος, end

47, ‘Αποκάλυψις, Apocalypse

48, ‘Απόκρυφα, Apocrypha

49, Ἠλεκτρον (Elektron), electric

50, Metamorphosis, Μεταμόρφωσις

51, Bimah, βῆμα

52, ἰχθύς (ichthýs) and ψάρι (psari), fish.

53, Τὰ Βιβλία (Ta Biblia), The Bible

Greek books in a second-hand bookshop in Souliou Street, Rethymnon … the English word Bible is derived from the Koinē Greek τὰ βιβλία meaning ‘the books’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)