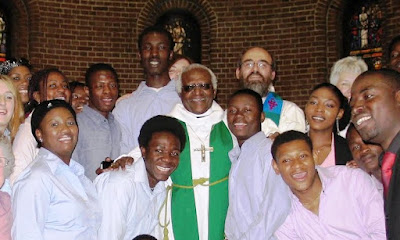

With Archbishop Desmond Tutu and members of the Discovery Gospel Choir in Dublin in 2005

Patrick Comerford

I was saddened to hear the news this morning that Archbishop Desmond Tutu has died at the age of 90.

When he received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984, I profiled Archbishop Desmond Tutu for The Irish Times. We had met previously, at events co-hosted by AfrI and Christian CND and at dinner in Roebuck House, Seán MacBride’s house in Clonskeagh, Dublin.

I asked him about the death threats he faced in South Africa at the height of apartheid. He engaged me with that look that confirmed his deep hope, commitment and faith, and said: ‘But you know, death is not the worst thing that could happen to a Christian.’

He must have been tempted at times to give up being a thorn in the side of the regime, to stop being a ‘turbulent priest,’ and to live a comfortable life. But his conscience would never have been comfortable.

As a young adult who had recently come to experience the love of God and started to explore the challenges of Christian discipleship, I was deeply challenged by the witness of one of his predecessors as Dean of Johannesburg, who opened the doors of his cathedral and offered sanctuary to black protesters who were being beaten on the cathedral steps by white police using rhino whips.

Dean Gonville ffrench-Beytagh knew the consequences. He was jailed, and eventually exiled from South Africa. To use the words of the German martyr, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, he bore the ‘Cost of Discipleship.’ Some years later, while apartheid was still in force, Desmond Tutu became Dean of Saint Mary’s in Johannesburg, and when I first met him, he was the secretary general of the South African Council of Churches.

I was worried about the many death threats he was receiving, and I asked him how he lived with those threats. Was he worried about them? Did he ever consider modifying what he had to say because of them? His answer was similar to the one he gave when he was facing tough questioning before the regime’s Eloff Commission. He told that inquiry:

‘There is nothing the government can do to me that will stop me from being involved in what I believe God wants me to do. I do not do it because I like doing it. I do it because I am under what I believe to be the influence of God’s hand. I cannot help it. When I see injustice, I cannot keep quiet, for, as Jeremiah says, when I try to keep quiet, God’s Word burns like a fire in my breast. But what is it that they can ultimately do? The most awful thing that they can do is to kill me, and death is not the worst thing that could happen to a Christian.’

With Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Seán MacBride and Bruce Kent in Roebuck House, Dublin, in the early 1980s

In 1987, Veritas invited me to write a short, 36-page biography of Archbishop Tutu, published as Desmond Tutu: Black Africa’s Man of Destiny. It was launched by the then Minister for Foreign Affairs, Brian Lenihan. It was a small book, hardly more than a pamphlet, but it came at an important time when both the Irish Government and the Irish Churches were becoming increasingly vocal about the evils of apartheid.

It was republished as a paperback in the US by Citadel in 1988 and by Hyperion Books in 1989, and when I was visiting South Africa in 1990 with The Irish Times and Christian Aid, I met him in Cape Town, where once again he spoke powerfully about the changes that were beginning to take place.

We kept in touch for many years, exchanging Christmas cards and greetings, and I have many of his signed books on my bookshelves.

Then, when my colleague Patsy McGarry was organising a monumental series of one-page features in The Irish Times in 2000 to mark the millennium, Archbishop Tutu was one of the international writers who contributed, along with Hans Küng, Andrew Greeley and Mary Robinson. The complete series was published by Veritas the following year as a book, Christianity, in which Part Two was my ‘Brief History of Christianity.’

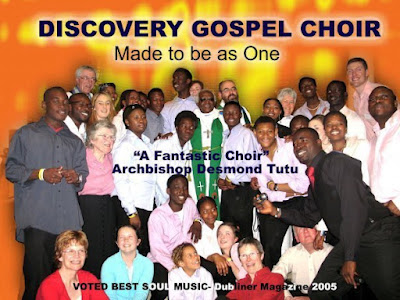

We last met when he visited Dublin in 2005, and he preached in Saint George’s and Saint Thomas’s Church in the inner city, where Canon Katharine Poulton was then the Rector, as part of the Discovery Gospel Choir services.

With Archbishop Desmond Tutu on the cover of a Discovery Gospel Choir CD

26 December 2021

With the Saints through Christmas (1):

26 December 2021, Saint Stephen

A mosaic depicting Saint Stephen in the Church of Saint Stephen Walbrook, London (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Patrick Comerford

Our Christmas celebrations may be more restrained and tempered this morning. But Christmas is not over, and, indeed, it does not end even after the ’12 Days of Christmas,’ but is a season that continues for 40 days until the Feast of the Presentation or Candlemas (2 February).

After a busy Christmas week, I am resting in Dublin today before returning to Askeaton tomorrow. But, before this day begins, I am taking some time early this morning for prayer, reflection and reading.

I have decided to continue my Prayer Diary on my blog each morning, reflecting in these ways:

1, Reflections on a saint remembered in the calendars of the Church during Christmas;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

I find it hard to call 26 December ‘Boxing Day.’ For me, 26 December is always going to be Saint Stephen’s Day.

It is theologically important to remind ourselves on the day after Christmas Day of the important link between the Incarnation and bearing witness to the Resurrection faith.

Saint Stephen’s Day today [26 December], Holy Innocents’ Day (28 December), and the commemoration of Thomas à Beckett on 29 December are reminders that Christmas, far from being surrounded by sanitised images of the crib, angels and wise men, is followed by martyrdom and violence. Close on the joy of Christmas comes the cost of following Christ. A popular expression, derived from William Penn, says: ‘No Cross, No Crown.’

Saint Stephen (Στέφανος, Stephanos) is the first martyr of Christianity. His name is derived from the Greek word meaning ‘crown,’ and traditionally, he carries the crown of martyrdom. In iconography, Saint Stephen the Deacon is often depicted as a young, beardless man, with a deacon’s stole and holding three stones of his martyrdom and the martyrs’ palm.

According to the brief New Testament account of his life and death (Acts 6:1 to 8: 2), Saint Stephen is one of the seven deacons selected by the Early Church in Jerusalem to attend to the needs of the Greek-speaking widows whose needs were being neglected. Stephen, and the other six deacons – Philip, Prochorus, Nicanor, Timon, Parmenas and Nicholas – all have Greek names.

He was denounced for blasphemy later, and was tried before the Sanhedrin. During his trial, he had a vision of the Father and the Son: ‘Behold, I see the heavens opened, and the Son of man standing on the right hand of God’ (Acts 7: 56). He was condemned, taken outside the city walls and stoned to death. Among those who stoned him to death was Saul of Tarsus, later the Apostle Paul.

In the Old City of Jerusalem, the Lion’s Gate is also called Saint Stephen’s Gate, after the tradition that Saint Stephen was stoned to death there, although it probably took place at the Damascus Gate.

In the one of the early examples of irony in Western Europe, the Mediaeval Church designated Saint Stephen the patron saint of stonemasons and, for some time, he was also the patron saint of headaches.

Saint Stephen’s House, an Anglican theological college in Oxford, is at Iffley Road in the former monastery of the Cowley Fathers, where it is said Dietrich Bonhoeffer decided to return to Germany where he met with martyrdom.

Bonhoeffer’s martyrdom illustrates how the extension to the Christmas holiday provided by this saint’s day would have no meaning today without the faithful witness of Saint Stephen, the first deacon and first martyr, who links our faith in the Incarnation with our faith in the Resurrection.

The Martyrdom of Saint Stephen … a stained-glass window in Lichfield Cathedral (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

This day, the ‘Feast of Stephen,’ is also mentioned in the popular carol, Good King Wenceslas. The carol was published by John Mason Neale (1818-1866) in 1853, although he may have written it some time earlier, for he included the legend of Saint Wenceslas in his Deeds of Faith in 1849.

Good King Wenceslas looked out on the Feast of Stephen,

When the snow lay round about, deep and crisp and even.

Brightly shone the moon that night, though the frost was cruel,

When a poor man came in sight, gathering winter fuel.

‘Hither, page, and stand by me, if you know it, telling,

Yonder peasant, who is he? Where and what his dwelling?’

‘Sire, he lives a good league hence, underneath the mountain,

Right against the forest fence, by Saint Agnes’ fountain.’

‘Bring me food and bring me wine, bring me pine logs hither,

You and I will see him dine, when we bear them thither.’

Page and monarch, forth they went, forth they went together,

Through the cold wind’s wild lament and the bitter weather.

‘Sire, the night is darker now, and the wind blows stronger,

Fails my heart, I know not how; I can go no longer.’

‘Mark my footsteps, my good page, tread now in them boldly,

You shall find the winter’s rage freeze your blood less coldly.’

In his master’s steps he trod, where the snow lay dinted;

Heat was in the very sod which the saint had printed.

Therefore, Christian men, be sure, wealth or rank possessing,

You who now will bless the poor shall yourselves find blessing.

Although it is included in neither the Irish Church Hymnal nor the New English Hymnal, this carol retains its popularity, and I imagine it is going to sung in many places today.

Wenceslas was a 10th century Duke of Bohemia who was known for his saintly caring works for the poor. He became the patron saint of Bohemia (now part of the Czech Republic) and his feast day is on 28 September.

Saint Stephen’s witness to the faith and King Wenceslas’s care for the poor are reminders that the Christmas Spirit should not be confined or limited to Christmas Day.

It is said that when the German martyr Dietrich Bonhoeffer visited Saint Stephen’s House in Oxford he decided to return to Germany where he met with martyrdom.

Bonhoeffer’s martyrdom illustrates how none of this architecture or grandeur, and the extension to the Christmas holiday provided by this saint’s day would have any meaning today without the faithful witness of Saint Stephen, the first deacon and first martyr, who links our faith in the Incarnation with our faith in the Resurrection.

Saint Stephen in a fresco by Giotto in Florence

Matthew 10: 17-22 (NRSVA):

[Jesus said:] 17 ‘Beware of them, for they will hand you over to councils and flog you in their synagogues; 18 and you will be dragged before governors and kings because of me, as a testimony to them and the Gentiles. 19 When they hand you over, do not worry about how you are to speak or what you are to say; for what you are to say will be given to you at that time; 20 for it is not you who speak, but the Spirit of your Father speaking through you. 21 Brother will betray brother to death, and a father his child, and children will rise against parents and have them put to death; 22 and you will be hated by all because of my name. But the one who endures to the end will be saved.’

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (26 December 2021, Saint Stephen’s Day) invites us to pray:

Gracious God,

teach us to be compassionate,

humble and meek.

May we strive to be Christlike in

all we do.

Collect:

Gracious Father,

who gave the first martyr Stephen

grace to pray for those who stoned him:

Grant that in all our sufferings for the truth

we may learn to love even our enemies

and to seek forgiveness for those who desire our hurt,

looking up to heaven to him who was crucified for us,

Jesus Christ, our Mediator and Advocate,

who is alive and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

Tomorrow: Saint John the Evangelist.

‘Good King Wenceslas’ … an image on a ceiling in the Old Town Hall in Prague (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Patrick Comerford

Our Christmas celebrations may be more restrained and tempered this morning. But Christmas is not over, and, indeed, it does not end even after the ’12 Days of Christmas,’ but is a season that continues for 40 days until the Feast of the Presentation or Candlemas (2 February).

After a busy Christmas week, I am resting in Dublin today before returning to Askeaton tomorrow. But, before this day begins, I am taking some time early this morning for prayer, reflection and reading.

I have decided to continue my Prayer Diary on my blog each morning, reflecting in these ways:

1, Reflections on a saint remembered in the calendars of the Church during Christmas;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

I find it hard to call 26 December ‘Boxing Day.’ For me, 26 December is always going to be Saint Stephen’s Day.

It is theologically important to remind ourselves on the day after Christmas Day of the important link between the Incarnation and bearing witness to the Resurrection faith.

Saint Stephen’s Day today [26 December], Holy Innocents’ Day (28 December), and the commemoration of Thomas à Beckett on 29 December are reminders that Christmas, far from being surrounded by sanitised images of the crib, angels and wise men, is followed by martyrdom and violence. Close on the joy of Christmas comes the cost of following Christ. A popular expression, derived from William Penn, says: ‘No Cross, No Crown.’

Saint Stephen (Στέφανος, Stephanos) is the first martyr of Christianity. His name is derived from the Greek word meaning ‘crown,’ and traditionally, he carries the crown of martyrdom. In iconography, Saint Stephen the Deacon is often depicted as a young, beardless man, with a deacon’s stole and holding three stones of his martyrdom and the martyrs’ palm.

According to the brief New Testament account of his life and death (Acts 6:1 to 8: 2), Saint Stephen is one of the seven deacons selected by the Early Church in Jerusalem to attend to the needs of the Greek-speaking widows whose needs were being neglected. Stephen, and the other six deacons – Philip, Prochorus, Nicanor, Timon, Parmenas and Nicholas – all have Greek names.

He was denounced for blasphemy later, and was tried before the Sanhedrin. During his trial, he had a vision of the Father and the Son: ‘Behold, I see the heavens opened, and the Son of man standing on the right hand of God’ (Acts 7: 56). He was condemned, taken outside the city walls and stoned to death. Among those who stoned him to death was Saul of Tarsus, later the Apostle Paul.

In the Old City of Jerusalem, the Lion’s Gate is also called Saint Stephen’s Gate, after the tradition that Saint Stephen was stoned to death there, although it probably took place at the Damascus Gate.

In the one of the early examples of irony in Western Europe, the Mediaeval Church designated Saint Stephen the patron saint of stonemasons and, for some time, he was also the patron saint of headaches.

Saint Stephen’s House, an Anglican theological college in Oxford, is at Iffley Road in the former monastery of the Cowley Fathers, where it is said Dietrich Bonhoeffer decided to return to Germany where he met with martyrdom.

Bonhoeffer’s martyrdom illustrates how the extension to the Christmas holiday provided by this saint’s day would have no meaning today without the faithful witness of Saint Stephen, the first deacon and first martyr, who links our faith in the Incarnation with our faith in the Resurrection.

The Martyrdom of Saint Stephen … a stained-glass window in Lichfield Cathedral (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

This day, the ‘Feast of Stephen,’ is also mentioned in the popular carol, Good King Wenceslas. The carol was published by John Mason Neale (1818-1866) in 1853, although he may have written it some time earlier, for he included the legend of Saint Wenceslas in his Deeds of Faith in 1849.

Good King Wenceslas looked out on the Feast of Stephen,

When the snow lay round about, deep and crisp and even.

Brightly shone the moon that night, though the frost was cruel,

When a poor man came in sight, gathering winter fuel.

‘Hither, page, and stand by me, if you know it, telling,

Yonder peasant, who is he? Where and what his dwelling?’

‘Sire, he lives a good league hence, underneath the mountain,

Right against the forest fence, by Saint Agnes’ fountain.’

‘Bring me food and bring me wine, bring me pine logs hither,

You and I will see him dine, when we bear them thither.’

Page and monarch, forth they went, forth they went together,

Through the cold wind’s wild lament and the bitter weather.

‘Sire, the night is darker now, and the wind blows stronger,

Fails my heart, I know not how; I can go no longer.’

‘Mark my footsteps, my good page, tread now in them boldly,

You shall find the winter’s rage freeze your blood less coldly.’

In his master’s steps he trod, where the snow lay dinted;

Heat was in the very sod which the saint had printed.

Therefore, Christian men, be sure, wealth or rank possessing,

You who now will bless the poor shall yourselves find blessing.

Although it is included in neither the Irish Church Hymnal nor the New English Hymnal, this carol retains its popularity, and I imagine it is going to sung in many places today.

Wenceslas was a 10th century Duke of Bohemia who was known for his saintly caring works for the poor. He became the patron saint of Bohemia (now part of the Czech Republic) and his feast day is on 28 September.

Saint Stephen’s witness to the faith and King Wenceslas’s care for the poor are reminders that the Christmas Spirit should not be confined or limited to Christmas Day.

It is said that when the German martyr Dietrich Bonhoeffer visited Saint Stephen’s House in Oxford he decided to return to Germany where he met with martyrdom.

Bonhoeffer’s martyrdom illustrates how none of this architecture or grandeur, and the extension to the Christmas holiday provided by this saint’s day would have any meaning today without the faithful witness of Saint Stephen, the first deacon and first martyr, who links our faith in the Incarnation with our faith in the Resurrection.

Saint Stephen in a fresco by Giotto in Florence

Matthew 10: 17-22 (NRSVA):

[Jesus said:] 17 ‘Beware of them, for they will hand you over to councils and flog you in their synagogues; 18 and you will be dragged before governors and kings because of me, as a testimony to them and the Gentiles. 19 When they hand you over, do not worry about how you are to speak or what you are to say; for what you are to say will be given to you at that time; 20 for it is not you who speak, but the Spirit of your Father speaking through you. 21 Brother will betray brother to death, and a father his child, and children will rise against parents and have them put to death; 22 and you will be hated by all because of my name. But the one who endures to the end will be saved.’

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (26 December 2021, Saint Stephen’s Day) invites us to pray:

Gracious God,

teach us to be compassionate,

humble and meek.

May we strive to be Christlike in

all we do.

Collect:

Gracious Father,

who gave the first martyr Stephen

grace to pray for those who stoned him:

Grant that in all our sufferings for the truth

we may learn to love even our enemies

and to seek forgiveness for those who desire our hurt,

looking up to heaven to him who was crucified for us,

Jesus Christ, our Mediator and Advocate,

who is alive and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

Tomorrow: Saint John the Evangelist.

‘Good King Wenceslas’ … an image on a ceiling in the Old Town Hall in Prague (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)