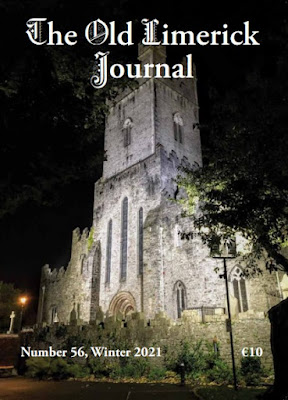

The latest edition of the ‘Old Limerick Journal’ … the front cover includes my photograph of Saint Mary’s Cathedral, Limerick

Patrick Comerford

I had an afternoon in Limerick earlier this week, browsing in the book shops, buying a few journals and books, and also visiting Saint Mary’s Cathedral.

I failed, in all the bookshops I visited to find a copy of Hilary Dully’s new book, her edited volume of the papers of the revolutionary Máire Comerford, On Dangerous Ground. Although it is only three weeks since it was published, the book seems to be a best-seller already, if not sold out.

Among the journals I bought was the latest edition of the Old Limerick Journal (No 56, Winter 2021), edited by Tom Donovan and published by the Limerick Museum at the Old Franciscan Friary on Henry Street, Limerick.

It is a particular pleasure for me that this new edition of the Old Limerick Journal features one of my photographs of Saint Mary’s Cathedral, Limerick, as its front cover illustration, with a complimentary credit and description of me inside on the title page.

As always, this edition of the Old Limerick Journal is filled with fascinating research by local historians.

For example, Des Ryan in his paper searches for ‘The Origins of the Limerick Jewish Community’ (pp 13-15), and asks whether the local newspapers were right in the 1890s to describe them as ‘Polish’ or even, on one occasion, ‘a Polish colony.’

He looks at the background of the 31 Jewish families living in Limerick at the time of the 1901 census, and finds that while one family give Poland as their place of origin, the other 30 families record Russia as their place of birth. In reality, most of them came from Lithuania, then part of the Russian Empire.

At the time, more than 5 million people were living in an area known as ‘the Pale,’ which stretched from parts of Latvia in the north, to Odessa and the Black Sea in the south, including large parts of present-day Lithuania, Latvia, Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus and Poland.

Many of Jewish families in these regions fled the persecutions and pogroms that intensified after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881.

Des Ryan, who is the longest-running contributor to Old Limerick Journal and a member of the journal’s editorial committee, provides an interesting and invaluable list of the Jewish families living in Limerick in 1901, many of them in Collooney Street (now Wolfe Tone Street) and the surrounding area. Once, again, I believe Limerick needs a Jewish Walking Trail, like those in many European cities.

Joseph Lennon asks how the castle in Limerick became known as ‘King John’s Castle’ (pp 29-36). This particular name first appears in 1787, but King John also gives his name to a castle in Carlingford, Co Louth, and to a number of castles in England.

King John gave Limerick its first charter in 1197, and confirmed it as king in 1199. But there is no primary evidence that he ever visited Limerick. The castle was known throughout most of its history as Limerick Castle, although on occasions it was referred to as ‘the king’s castle.’

The Limerick-born historian John Ferrar was the first to refer to it as ‘King John’s Castle’ when he published a new edition of his History of Limerick in 1787, and this has influenced writers and historians ever since.

Brian Hodkinson, a former curator of the Limerick Museum, is thorough in examining the myths that the Knights Templar established a number of houses in Co Limerick (pp 37-39). These include house at Askeaton, Ballingarry, Castle Matrix, Kildimo, Morgans Newcastle, Shanid, Templecolman and Templeglantine, all in this part of West Limerick.

I have long argued that there is no evidence for a Templar foundation at Saint Mary’s Church, Askeaton. This is a misinterpretation of the significance of the ‘unusual shape’ of the tower, which changes from a square base to an octagonal structure as it rises.

But Askeaton, like many of these churches, was a dependency of Keynsham Abbey, an Augustinian house in Somerset. He poses the question, ‘The Knights Templar in Limerick; fact or fiction?’ He concludes ‘the answer to the question posed in the title is, fiction.’

The Old Limerick Journal Number 56, Winter 2021, ISBN: 9781916294332, €10 is available in all good bookshops in Limerick and through the museums in Limerick.

Saint Mary’s Cathedral, Limerick … my photograph on the cover of the latest edition of the ‘Old Limerick Journal’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2021)

15 December 2021

Praying in Advent 2021:

18, Saint Nino of Georgia

Saint Nino, who brought Christianity to Georgia, is celebrated on 15 December

Patrick Comerford

This is a busy day, with project meetings in Rathkeale, and a select vestry meeting this evening. But, before this busy day begins, I am taking some time early this morning for prayer, reflection and reading.

Each morning in my Advent calendar this year, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, Reflections on a saint remembered in the calendars of the Church during Advent;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

This morning, my choice of saint is Sant Nino, who is remembered in the calendars of many Orthodox Churches on 15 December as the patron saint of Georgia, but who seems almost unknown in the Churches of the West.

Saint Nino (Greek, Αγία Νίνα, Agía Nína) is called Equal to the Apostles and the Enlightener of Georgia. Saint Nina (ca 296 to ca 338 or 340) She preached Christianity in Caucasian Iberia, in what is now part of Georgia, bringing Christianity to Iberia and the royal house.

Most traditions say she belonged to a Greek-speaking Roman family from Kolastra or Colastri in Cappadocia. Her father was a Roman general Zabulon and her mother was Sosana or Susan. Her father’s family was related to Saint George; on her mother’s side, her uncle was Patriarch Houbnal I of Jerusalem. She is said to have come to ancient Iberia or Georgia from Constantinople.

In her childhood, Nino was brought up by the nun Niofora-Sarah of Bethlehem. With the help of her uncle the patriarch, she went to Rome and there she decided to preach the Gospel in Iberia. On her way, she escaped persecution by the Armenian King Tiridates III of Armenia, but the other members of her community of 35 were tortured and beheaded by Tiridates.

The Iberian Kingdom had been influenced by the neighbouring Persian Empire, then the regional power in the Caucasus, and King Mirian III and his people worshiped the syncretic gods Armazi and Zaden.

Soon after Saint Nino arrived in Mtskheta, an ailing Queen Nana sked to meet her. Saint Nino performed miraculous healings, and Queen Nana’s health was restored. She converted to Christianity and was baptised by Saint Nino herself.

Later, King Mirian III of Iberia was lost in darkness and blinded on a hunting trip. He found his way home only after he prayed to ‘Nino’s God.’ King Mirian declared Christianity the official religion of his kingdom ca in 327, making Iberia the second Christian state after Armenia.

After Georgia adopted Christianity, King Mirian sent an ambassador to Byzantium, asking Emperor Constantine I to have a bishop and priests sent to Iberia. Constantine granted the new church land in Jerusalem and sent a delegation of bishops to the court of the Georgian King. In 334, King Mirian commissioned building the first church in Iberia. It was completed in 379, and the Svetitskhoveli Cathedral now stands on the site in Mtskheta.

Saint Nino continued her missionary activities among Georgians until she died. Her tomb is in the Bodbe Monastery in Kakheti, east Georgia.

All 35 members of her original community, including Saint Nino, have been canonised by the Armenian Apostolic Church. Nino and its variants remain the most popular name for women and girls in the Georgia.

Luke 7: 18b-23 (NRSVA):

18 The disciples of John reported all these things to him. So John summoned two of his disciples 19 and sent them to the Lord to ask, ‘Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?’ 20 When the men had come to him, they said, ‘John the Baptist has sent us to you to ask, “Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?” ’ 21 Jesus had just then cured many people of diseases, plagues, and evil spirits, and had given sight to many who were blind. 22 And he answered them, ‘Go and tell John what you have seen and heard: the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, the poor have good news brought to them. 23 And blessed is anyone who takes no offence at me.’

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (15 December 2021) invites us to pray:

Let us pray for the Church of North India, comprised of 27 dioceses across northern India.

An icon showing Saint Nino and episodes in her life

Yesterday: Saint Lucy of Syracuse

Tomorrow: Saint Eleftherios

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Patrick Comerford

This is a busy day, with project meetings in Rathkeale, and a select vestry meeting this evening. But, before this busy day begins, I am taking some time early this morning for prayer, reflection and reading.

Each morning in my Advent calendar this year, I am reflecting in these ways:

1, Reflections on a saint remembered in the calendars of the Church during Advent;

2, the day’s Gospel reading;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary.

This morning, my choice of saint is Sant Nino, who is remembered in the calendars of many Orthodox Churches on 15 December as the patron saint of Georgia, but who seems almost unknown in the Churches of the West.

Saint Nino (Greek, Αγία Νίνα, Agía Nína) is called Equal to the Apostles and the Enlightener of Georgia. Saint Nina (ca 296 to ca 338 or 340) She preached Christianity in Caucasian Iberia, in what is now part of Georgia, bringing Christianity to Iberia and the royal house.

Most traditions say she belonged to a Greek-speaking Roman family from Kolastra or Colastri in Cappadocia. Her father was a Roman general Zabulon and her mother was Sosana or Susan. Her father’s family was related to Saint George; on her mother’s side, her uncle was Patriarch Houbnal I of Jerusalem. She is said to have come to ancient Iberia or Georgia from Constantinople.

In her childhood, Nino was brought up by the nun Niofora-Sarah of Bethlehem. With the help of her uncle the patriarch, she went to Rome and there she decided to preach the Gospel in Iberia. On her way, she escaped persecution by the Armenian King Tiridates III of Armenia, but the other members of her community of 35 were tortured and beheaded by Tiridates.

The Iberian Kingdom had been influenced by the neighbouring Persian Empire, then the regional power in the Caucasus, and King Mirian III and his people worshiped the syncretic gods Armazi and Zaden.

Soon after Saint Nino arrived in Mtskheta, an ailing Queen Nana sked to meet her. Saint Nino performed miraculous healings, and Queen Nana’s health was restored. She converted to Christianity and was baptised by Saint Nino herself.

Later, King Mirian III of Iberia was lost in darkness and blinded on a hunting trip. He found his way home only after he prayed to ‘Nino’s God.’ King Mirian declared Christianity the official religion of his kingdom ca in 327, making Iberia the second Christian state after Armenia.

After Georgia adopted Christianity, King Mirian sent an ambassador to Byzantium, asking Emperor Constantine I to have a bishop and priests sent to Iberia. Constantine granted the new church land in Jerusalem and sent a delegation of bishops to the court of the Georgian King. In 334, King Mirian commissioned building the first church in Iberia. It was completed in 379, and the Svetitskhoveli Cathedral now stands on the site in Mtskheta.

Saint Nino continued her missionary activities among Georgians until she died. Her tomb is in the Bodbe Monastery in Kakheti, east Georgia.

All 35 members of her original community, including Saint Nino, have been canonised by the Armenian Apostolic Church. Nino and its variants remain the most popular name for women and girls in the Georgia.

Luke 7: 18b-23 (NRSVA):

18 The disciples of John reported all these things to him. So John summoned two of his disciples 19 and sent them to the Lord to ask, ‘Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?’ 20 When the men had come to him, they said, ‘John the Baptist has sent us to you to ask, “Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?” ’ 21 Jesus had just then cured many people of diseases, plagues, and evil spirits, and had given sight to many who were blind. 22 And he answered them, ‘Go and tell John what you have seen and heard: the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, the poor have good news brought to them. 23 And blessed is anyone who takes no offence at me.’

The Prayer in the USPG Prayer Diary today (15 December 2021) invites us to pray:

Let us pray for the Church of North India, comprised of 27 dioceses across northern India.

An icon showing Saint Nino and episodes in her life

Yesterday: Saint Lucy of Syracuse

Tomorrow: Saint Eleftherios

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)