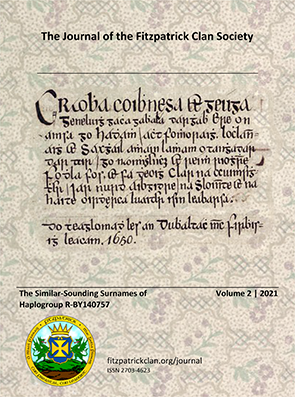

The ‘Journal of the Fitzpatrick Clan Society’ (2021) … Dr Mike Fitzpatrick challenges some myths and legends of the origins of the Brennan families

Patrick Comerford

It is always interesting, in academic terms, to see how other historians and genealogists carry out their research and check their sources. And – setting aside personal vanity – it is always rewarding, in an academic terms, to see how my own research is referenced by other researchers in their papers.

In recent days, my attention has been drawn to ‘The Similar-Sounding Surnames of Haplogroup R-BY140757,’ a paper last year by Dr Mike Fitzpatrick of the University of Auckland, and published in the Journal of the Fitzpatrick Clan Society 2 (2021), pp 1-41.

Y-DNA analysis is a remarkable method that can inform patrilineal genealogies, both ancient, and modern. Applied here to facilitate a critical review of Branan pedigrees, an analysis of haplogroup R-BY140757 results in a deep questioning of the dominant narratives of the O’Braonáin Uí Dhuach (O’Brenan of Idough). What results is a disruption of those narratives that is total.

The O’Braonáin Uí Dhuach were long said by historians of Ossory to share descent from Cearbhall, King of Ossory (843-888 AD). However, the ultimate genealogical authority of Dubhaltach Mac Fhirbhisigh led to the argument that these families are not of Ossory descent, but are an Uí Failghi tribe.

As he set out on his research, Mike Fitzpatrick realised than Y-DNA connections between Branans, or those with similar-sounding surnames such as Brennan, and other connected families, are a false trail for those who claim descent from Cearbhall.

Once Mac Fhirbhisigh is embraced, he found, and the erroneous pedigrees of the O’Braonáin Uí Dhuach are set aside, the origins of men with the name Branan, and similar-sounding surnames, of haplogroup R-BY140757, can be correctly determined.

With an analysis of Y-DNA haplotype research, Dr Fitzpatrick has concluded the origins of these families are not with the O’Braonáin of Uí Dhuach, or any Irish clan. ‘Rather, haplotype R-BY140757 appears to have originated from a family who settled near Braham, in Suffolk, after the Norman conquest of England.’

He identifies the key figure in the appearance of R-BY140757 pedigrees in Ireland as Sir Robert de Braham, who was Sheriff of Kilkenny ca 1250.

Genealogists constantly face a battle of the brains with families who continue to prefer to perpetuate myths about family origins, repeated and retold over the generations and down through time, instead of accepting research that uses the accepted tools of modern historical research that demands primary sources and refuses to accept past genealogical constructs that satisfied the vanities of family members in the past.

All genealogists working on the stories of families know the pitfalls of accepting the family trees and pedigrees confirmed in the past by the Ulster Office of Arms or repeated uncritically by John O’Hart and even in volumes such as Burke’s Peerage and Burke’s Landed Gentry.

Although I have constantly produced evidence for the origins of the Comerford family in Co Kilkenny and south-east Ireland, the old tales keep being peddled on many websites that rely on a ‘copy-and-past’ approach rather than genuine historical research as they sell their cheap name books and tardy mass-produced coats of arms and so-called heraldic scrolls.

In my research, I have had to cast a critical eye on the research and work of even more recent historians, including Canon William Carrigan, despite his often-painstaking work in compiling his four-volume History of the Diocese of Ossory, published in 1905.

Mike Fitzpatrick’s research came to my attention recently because he refers to an earlier paper in 2005 in which I drew attention to the way Carrigan avoided a critical approach to the lives of clergy in his diocese, including Edmund Comerford, Bishop of Ferns and Dean of Ossory, and his son, William Comerford, Dean of Ossory, who is described in many places as the bishop’s newphew rather than son.

Drawing on my paper, published as ‘The last pre-reformation Bishop of Ferns and his ‘nephew’, the Dean of Ossory,’ in the Journal of the Wexford Historical Society, 20 (2005), pp 156-172, Fitzpatrick concedes that Carrigan is ‘excellent in many respects,’ but agrees that he ‘was possibly also subject to conflicts of interest; he was a sidestepper of unbecoming acts by clergy.’

He also says Carrigan ‘avoided an exposition of the clerical lineages of Mac Giolla Phádraig Osraí,’ the FitzPatricks of Ossory, ‘which must have been known to him,’ although he concedes that ‘the suite of Papal records available to Carrigan was not as complete as it is today.’

Dr Fitzpatrick’s methodology and approach are important advances in genealogical research. In a paper this year, co-authored with Dan Fitzpatrick and Ian Fitzpatrick, he develops his scientific approaches to challenging traditional but myth-laden and fact-denying constructions of family trees and pedigrees.

Their latest paper, ‘Mac Giolla Phádraig Dál gCais: an ancient clan rediscovered,’ is published in the Journal of the Fitzpatrick Clan Society 2022 (3), pp 1-45.

They say that Y-DNA analysis of Fitzpatricks has turned traditional historical narratives of how the surname was taken on its head. ‘The attachment of the surname Fitzpatrick to the Barons of Upper Ossory, who were supposedly the descendants of Mac Giolla Phádraig Osraí and, in turn, of an ancient [Leinster] lineage, is no longer sustainable.’

They go on to say that ‘DNA insights and critical assessment of historical records have demonstrated that those who claim to descend from the barons [of Upper Ossory] have a Y-haplotype consistent with them emerging from a line of clerics out of a Norman-Irish origin ca 1200 AD.’

They say that questions now arise ‘regarding the origins of other large Fitzpatrick groups who, based on Y-DNA, can be shown to descend from ancient Irish.’ And they ask, ‘Could any of these lines descend from the Mac Giolla Phádraig Osraí of old, those of Annalistic fame?’

They question the origins of the Mac Giolla Phádraig or Fitzpatrick family that claimed an ancient lineage with origins in Ossory. They say their questions radically disrupt traditional narratives, point how ‘sound historical, genealogical, and name occurrence evidence supports the view’ that there is no need to adhere to a singular patrimony for the Mac Giolla Phádraig Osraí or Fitzpatricks of Ossory.

Instead, they show in their latest paper, the FitzPatricks of Ossory ‘are Dál gCais on a genetic basis since, via their paternal haplotype, they share common ancestry with Brian Bóruma, High King of Ireland.’

The descendants of those Mac Giolla Phádraig Dál gCais feature through ancient records for Co Clare and are still found in the county, yet, they suggest many derive from lines that were dispersed from their ancient Clare homelands in the 17th century.

From Co Clare to the Aran Islands, and Co Galway, and – one way or another – on to Mayo and Roscommon, ‘they are a great and ancient Mac Giolla Phádraig Clan,’ they say, ‘who at times held much wealth, power, and influence. And some were smugglers!’

Their work is a challenge to the way Irish genealogists have worked in the past, and is a pioneering approach to genealogical research in Ireland.

There are some interesting inter-marriages between the Comerford family of Ballybur and the FitzPatricks of Ossory. For example, Richard Comerford (1564-1637), of Ballybur Castle was the father of Ellinor Comerford, who married her second cousin, the Hon Dermot FitzPatrick, son of Thady FitzPatrick, 4th Baron Upper Ossory. Anne Langton, who married James Comerford of the Butterlsip, Kilkenny, was a half-sister of Mary Fitzpatrick, who also lived at the Butterslip.

But for some of the details of Ellinor Comerford and Dermot Fitzpatrick I have relied in the past on Carrigan, and the pedigrees of the FitzPatricks of Gowran and Upper Ossory in Burke’s Extinct Peerage and the Complete Peerage. I may have to revisit some of those sources in time.

The ‘Journal of the Fitzpatrick Clan Society’ (2022) … Dr Mike Fitzpatrick challenges some myths and legends of the origins of the FitzPatrick families of Upper Ossory

08 October 2022

Praying in Ordinary Time with USPG:

Saturday 8 October 2022

Saint Saviourgate Unitarian Church, the earliest surviving ‘nonconformist’ chapel in York, dates from 1693 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Patrick Comerford

Before today gets busy, I am taking some time this morning for reading, prayer and reflection.

Throughout this week and last, I have been reflecting each morning on a church, chapel, or place of worship in York, where I stayed in mid-September.

In my prayer diary this week I am reflecting in these ways:

1, One of the readings for the morning;

2, Reflecting on a church, chapel or place of worship in York;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary, ‘Pray with the World Church.’

Saint Andrew’s Evangelical Church, Spen Lane, is the home of a congregation of ‘open’ Plymouth Brethren (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Luke 11: 27-28 (NRSVA):

27 While he was saying this, a woman in the crowd raised her voice and said to him, ‘Blessed is the womb that bore you and the breasts that nursed you!’ 28 But he said, ‘Blessed rather are those who hear the word of God and obey it!’

Saint Columba’s United Reformed Church on Priory Street, near Micklegate Bar, was built in 1879 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

‘Nonconformists’ and ‘Dissenters’ in York:

This series of reflections on York churches concludes this morning as I look at five buildings that represent the ‘Nonconformist’ and ‘Dissenting’ tradition in York: the Unitarian Chapel, Saint Columba’s United Reformed Church, York Baptist Church, the Friargate Quaker Meeting House, and Saint Andrew’s Evangelical Church.

Saint Saviourgate Unitarian Chapel is the earliest surviving ‘nonconformist’ chapel in York. The early presence of ‘nonconformists’ and ‘dissenters’ in York can be traced back to the Puritans of the early and mid-17th century. After the Caroline restoration and within a decade of the ejection of 1662, five men were licensed in York as independent preachers in 1672, and several houses were licensed for worship.

By 1676, 161 ‘dissenters’ were recorded in York. Sir John and Lady Hewley, Lady Watson and Lady Lister used their influence to protect Ralph Ward and other dissenting ministers, and favoured both Presbyterians and Independents or Congregationalists equally.

After Ward died in 1691, his congregation began building Saint Saviourgate Chapel, also known as Lady Hewley’s Chapel, and it was registered in 1693. The building is in the form of a Greek cross, with each limb equal in area to the central intersection.

Lady Hewley, one of the original benefactors of the chapel, made an allowance to the minister during her lifetime and made provision for this allowance to continue after her death.

A Presbyterian congregation continued to attend the chapel until 1756, when the trustees of the Hewley Charity appointed Newcome Cappe as the minister, despite vocal opposition. He introduced Arianism and during his ministry the congregation declined, leaving only a small number who had adopted his views. Later, the chapel became Unitarian.

The Hewley Charity became the subject of legal action in the 1830s. After protracted litigation, the trustees of the charity were removed in 1836, and the minister’s stipend was no longer augmented from Lady Hewley’s charity.

The Unitarian use of the chapel was not affected and there was an average Sunday attendance of 120 in 1851. The Revd Charles Wellbeloved (1769-1858), principal of Manchester College, York – now Harris Manchester College, Oxford – and a noted local antiquary, was minister of the chapel in 1801-1858.

However, the loss of Lady Hewley’s endowments left the congregation struggling financially. Ministers quickly came and went or combined their ministry with other employment. One minister, George Saville Woods, was an MP at the same time as being chapel minister.

York Unitarian Chapel is member of the General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches. The chapel is a Grade II* listed building. York Unitarians recently marked their 350th anniversary as a congregation. Services are at 11 a.m. every Sunday. The minister is the Revd Stephanie Bisby.

The Unitarian Church in York is in the form of a Greek cross, with each limb equal in area to the central intersection (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Two strands of the Nonconformist tradition in York, the Presbyterians and the Congregationalists, are represented by Saint Columba’s United Reformed Church at 32 Priory Street, near Micklegate Bar.

Following a long gap after the divisions in the Presbyterian Church that became the Unitarian Church on Saint Saviourgate, Presbyterian services in York were started once again in 1873 in the Lecture Hall, Goodramgate, by a Presbyterian minister from Hull.

A site was acquired at the corner of Priory Street and Lower Priory Street, the foundation stone of Saint Columba’s Church was laid in January 1879, and the first service was held on 6 November. The building was designed to hold 700 worshippers at a time when York was a booming railway centre and a garrison town, with large numbers of Scottish and Irish workers, many with Presbyterian backgrounds. These Irish and Scottish connections are reflected in the name of Saint Columba of Iona.

The first minister was the Revd James Collie. His family presented three Pre-Raphaelite stained glass windows after his death in 1912. The church is built of white brick with decorated windows and there are two main entrances approached by flights of steps. A harmonium was installed in 1881, and was replaced with a pipe organ in 1907 with a Lewis Organ that was fully restored and modernised in 2008.

The church once had a tower, but this was removed in 1949. Some of the cast-iron railings remain.

The United Reformed Church (URC) was formed 50 years ago with the union of the Presbyterian Church of England and the Congregational Church in England and Wales in 1972, joined later by the Churches of Christ (1981) and the Congregational Union of Scotland (2000).

The Revd Alison Micklem is the Minister of Saint Columba’s United Reformed Church. Sunday services are at 10:15.

There was an Anabaptist congregation in York in the mid-1640s, and there are references to Baptist preachers in York in the 1670s and 1680s. But the current Baptist presence dates from around 1800, when some Wesleyan Methodists seceded and were later known as the Unitarian Baptists after they broke with Lady Huntingdon’s Connexion, which had a chapel in College Street.

By 1816, the Unitarian Baptists were using the Congregational chapel in Jubbergate, but by the 1830s they seem to have merged with the Unitarian chapel in Saint Saviourgate.

A second Baptist society emerged in York in 1799-1802 and met in a chapel in College Street until 1806, when they bought a chapel in Grape Lane. They seem to have faded away in the mid-1830s.

Baptist services resumed in York in 1862 in a hired room in the Lecture Hall, Goodramgate. A church of 30 members was formed in 1864 and the Baptist Chapel on Priory Street opened in 1868.

York Baptist Church on Priory Street, is a stone-faced building in Gothic style, designed by William Peachey of Darlington.

The Revd John Green was appointed as pastor of York Baptist Church last March after filling the role of interim minister since September 2020. Sunday services are at 10:45 am and 6:30 pm.

Friends’ Meeting House in Friargate in the centre of York is one of three Quaker Meetings in York. Quakers have worshipped in York since 1651.

Friargate Meeting House is a modern building, but Quakers have been worshipping on the site since the early days of the Society of Friends in the mid-17th century. George Fox, the founding Quaker, visited York in 1651, when he was roughly handled and forcibly thrown out of York Minster when he delivered his own religious message after the conclusion of the sermon. Many early Quakers were imprisoned in York Castle.

The first meeting house in York was planned in 1673, and was completed the following year. Edward Nightingale lived in Far Water Lane, now Friargate, and took a 99-year lease on property adjoining his home. The property was converted into a Quaker meeting house, and by 1681 a porch, gallery and stable were added.

Quaker worship has continued in the same area ever since. The meeting house was rebuilt in 1816-1817, and a new building opened in 1885. Until the early 1970s, the pupils and staff of the two York Quaker schools in York, Bootham and the Mount, attended Sunday worship. The meeting house was rebuilt in the 1980s, incorporating elements of the old meeting house, and opened in 1981.

Meeting for Worship takes place on Sundays at 10.30 am and lasts for an hour. The meeting holds a peace vigil once a month outside Saint Michael Le Belfrey church.

Saint Andrew’s Evangelical Church on Spen Lane has been the home of a congregation of ‘open’ Plymouth Brethren since 1924. The church was rebuilt from Saint Andrew’s Church, one of the oldest churches in York. Saint Andrew’s was mentioned in the Domesday Book, and there was a church on the site in 1194.

From 1331 until 1443, the church was dependent on Saint Martin, Coney Street. The oldest surviving part of the building is the chancel, completed in 1392, while the nave was built in the 15th century.

The church was closed in 1559, and the parish was merged with that Saint Saviour, Saint Saviourgate, in 1586. Since then, the building had a variety of uses. At the start of the 18th century, it was both a stable and a brothel. From about 1730, it was Saint Peter’s School, and from 1823 it was an infant school. By then, the chancel was a ruin, but by 1850 it was rebuilt as a cottage.

Before moving to Saint Andrew’s, this group of Brethren was using rooms in Micklegate, beside the Queen’s Hotel, in 1893, and continued to meet in the Gospel Hall in Micklegate until 1921. Their new meeting place was also known as ‘The Gospel Hall’ but is now called Saint Andrew’s Evangelical Church.

Most of the mediaeval walls of the church survive, with of a mixture of magnesian limestone, reused Roman gritstone blocks and brick infill. The chancel has one original window, and the nave has two. The chancel arch survived, blocked, and there is the lowest stage of a wooden bell turret, now inside the roof.

Friends’ Meeting House in Friargate is one of three Quaker meeting houses in York (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Today’s Prayer (Saturday 8 October 2022):

The Collect:

O Lord, we beseech you mercifully to hear the prayers

of your people who call upon you;

and grant that they may both perceive and know

what things they ought to do,

and also may have grace and power faithfully to fulfil them;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

The Post Communion Prayer:

Almighty God,

you have taught us through your Son

that love is the fulfilling of the law:

grant that we may love you with our whole heart

and our neighbours as ourselves;

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

The theme in the USPG Prayer Diary this week has been ‘Mission in a Crisis.’ This theme was introduced on Sunday by Father Rasika Abeysinghe, Priest in the Diocese of Kurunagala, Church of Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

The USPG Prayer Diary invites us to pray today in these words:

We pray for church institutions which are still recovering from the Covid pandemic. May we recognise that different countries are facing different challenges related to the pandemic.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

York Baptist Church on Priory Street opened in 1868 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

‘Take a Pew’ … a rainbow-coloured bench in front of York Unitarian Church (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Patrick Comerford

Before today gets busy, I am taking some time this morning for reading, prayer and reflection.

Throughout this week and last, I have been reflecting each morning on a church, chapel, or place of worship in York, where I stayed in mid-September.

In my prayer diary this week I am reflecting in these ways:

1, One of the readings for the morning;

2, Reflecting on a church, chapel or place of worship in York;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary, ‘Pray with the World Church.’

Saint Andrew’s Evangelical Church, Spen Lane, is the home of a congregation of ‘open’ Plymouth Brethren (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Luke 11: 27-28 (NRSVA):

27 While he was saying this, a woman in the crowd raised her voice and said to him, ‘Blessed is the womb that bore you and the breasts that nursed you!’ 28 But he said, ‘Blessed rather are those who hear the word of God and obey it!’

Saint Columba’s United Reformed Church on Priory Street, near Micklegate Bar, was built in 1879 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

‘Nonconformists’ and ‘Dissenters’ in York:

This series of reflections on York churches concludes this morning as I look at five buildings that represent the ‘Nonconformist’ and ‘Dissenting’ tradition in York: the Unitarian Chapel, Saint Columba’s United Reformed Church, York Baptist Church, the Friargate Quaker Meeting House, and Saint Andrew’s Evangelical Church.

Saint Saviourgate Unitarian Chapel is the earliest surviving ‘nonconformist’ chapel in York. The early presence of ‘nonconformists’ and ‘dissenters’ in York can be traced back to the Puritans of the early and mid-17th century. After the Caroline restoration and within a decade of the ejection of 1662, five men were licensed in York as independent preachers in 1672, and several houses were licensed for worship.

By 1676, 161 ‘dissenters’ were recorded in York. Sir John and Lady Hewley, Lady Watson and Lady Lister used their influence to protect Ralph Ward and other dissenting ministers, and favoured both Presbyterians and Independents or Congregationalists equally.

After Ward died in 1691, his congregation began building Saint Saviourgate Chapel, also known as Lady Hewley’s Chapel, and it was registered in 1693. The building is in the form of a Greek cross, with each limb equal in area to the central intersection.

Lady Hewley, one of the original benefactors of the chapel, made an allowance to the minister during her lifetime and made provision for this allowance to continue after her death.

A Presbyterian congregation continued to attend the chapel until 1756, when the trustees of the Hewley Charity appointed Newcome Cappe as the minister, despite vocal opposition. He introduced Arianism and during his ministry the congregation declined, leaving only a small number who had adopted his views. Later, the chapel became Unitarian.

The Hewley Charity became the subject of legal action in the 1830s. After protracted litigation, the trustees of the charity were removed in 1836, and the minister’s stipend was no longer augmented from Lady Hewley’s charity.

The Unitarian use of the chapel was not affected and there was an average Sunday attendance of 120 in 1851. The Revd Charles Wellbeloved (1769-1858), principal of Manchester College, York – now Harris Manchester College, Oxford – and a noted local antiquary, was minister of the chapel in 1801-1858.

However, the loss of Lady Hewley’s endowments left the congregation struggling financially. Ministers quickly came and went or combined their ministry with other employment. One minister, George Saville Woods, was an MP at the same time as being chapel minister.

York Unitarian Chapel is member of the General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches. The chapel is a Grade II* listed building. York Unitarians recently marked their 350th anniversary as a congregation. Services are at 11 a.m. every Sunday. The minister is the Revd Stephanie Bisby.

The Unitarian Church in York is in the form of a Greek cross, with each limb equal in area to the central intersection (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Two strands of the Nonconformist tradition in York, the Presbyterians and the Congregationalists, are represented by Saint Columba’s United Reformed Church at 32 Priory Street, near Micklegate Bar.

Following a long gap after the divisions in the Presbyterian Church that became the Unitarian Church on Saint Saviourgate, Presbyterian services in York were started once again in 1873 in the Lecture Hall, Goodramgate, by a Presbyterian minister from Hull.

A site was acquired at the corner of Priory Street and Lower Priory Street, the foundation stone of Saint Columba’s Church was laid in January 1879, and the first service was held on 6 November. The building was designed to hold 700 worshippers at a time when York was a booming railway centre and a garrison town, with large numbers of Scottish and Irish workers, many with Presbyterian backgrounds. These Irish and Scottish connections are reflected in the name of Saint Columba of Iona.

The first minister was the Revd James Collie. His family presented three Pre-Raphaelite stained glass windows after his death in 1912. The church is built of white brick with decorated windows and there are two main entrances approached by flights of steps. A harmonium was installed in 1881, and was replaced with a pipe organ in 1907 with a Lewis Organ that was fully restored and modernised in 2008.

The church once had a tower, but this was removed in 1949. Some of the cast-iron railings remain.

The United Reformed Church (URC) was formed 50 years ago with the union of the Presbyterian Church of England and the Congregational Church in England and Wales in 1972, joined later by the Churches of Christ (1981) and the Congregational Union of Scotland (2000).

The Revd Alison Micklem is the Minister of Saint Columba’s United Reformed Church. Sunday services are at 10:15.

There was an Anabaptist congregation in York in the mid-1640s, and there are references to Baptist preachers in York in the 1670s and 1680s. But the current Baptist presence dates from around 1800, when some Wesleyan Methodists seceded and were later known as the Unitarian Baptists after they broke with Lady Huntingdon’s Connexion, which had a chapel in College Street.

By 1816, the Unitarian Baptists were using the Congregational chapel in Jubbergate, but by the 1830s they seem to have merged with the Unitarian chapel in Saint Saviourgate.

A second Baptist society emerged in York in 1799-1802 and met in a chapel in College Street until 1806, when they bought a chapel in Grape Lane. They seem to have faded away in the mid-1830s.

Baptist services resumed in York in 1862 in a hired room in the Lecture Hall, Goodramgate. A church of 30 members was formed in 1864 and the Baptist Chapel on Priory Street opened in 1868.

York Baptist Church on Priory Street, is a stone-faced building in Gothic style, designed by William Peachey of Darlington.

The Revd John Green was appointed as pastor of York Baptist Church last March after filling the role of interim minister since September 2020. Sunday services are at 10:45 am and 6:30 pm.

Friends’ Meeting House in Friargate in the centre of York is one of three Quaker Meetings in York. Quakers have worshipped in York since 1651.

Friargate Meeting House is a modern building, but Quakers have been worshipping on the site since the early days of the Society of Friends in the mid-17th century. George Fox, the founding Quaker, visited York in 1651, when he was roughly handled and forcibly thrown out of York Minster when he delivered his own religious message after the conclusion of the sermon. Many early Quakers were imprisoned in York Castle.

The first meeting house in York was planned in 1673, and was completed the following year. Edward Nightingale lived in Far Water Lane, now Friargate, and took a 99-year lease on property adjoining his home. The property was converted into a Quaker meeting house, and by 1681 a porch, gallery and stable were added.

Quaker worship has continued in the same area ever since. The meeting house was rebuilt in 1816-1817, and a new building opened in 1885. Until the early 1970s, the pupils and staff of the two York Quaker schools in York, Bootham and the Mount, attended Sunday worship. The meeting house was rebuilt in the 1980s, incorporating elements of the old meeting house, and opened in 1981.

Meeting for Worship takes place on Sundays at 10.30 am and lasts for an hour. The meeting holds a peace vigil once a month outside Saint Michael Le Belfrey church.

Saint Andrew’s Evangelical Church on Spen Lane has been the home of a congregation of ‘open’ Plymouth Brethren since 1924. The church was rebuilt from Saint Andrew’s Church, one of the oldest churches in York. Saint Andrew’s was mentioned in the Domesday Book, and there was a church on the site in 1194.

From 1331 until 1443, the church was dependent on Saint Martin, Coney Street. The oldest surviving part of the building is the chancel, completed in 1392, while the nave was built in the 15th century.

The church was closed in 1559, and the parish was merged with that Saint Saviour, Saint Saviourgate, in 1586. Since then, the building had a variety of uses. At the start of the 18th century, it was both a stable and a brothel. From about 1730, it was Saint Peter’s School, and from 1823 it was an infant school. By then, the chancel was a ruin, but by 1850 it was rebuilt as a cottage.

Before moving to Saint Andrew’s, this group of Brethren was using rooms in Micklegate, beside the Queen’s Hotel, in 1893, and continued to meet in the Gospel Hall in Micklegate until 1921. Their new meeting place was also known as ‘The Gospel Hall’ but is now called Saint Andrew’s Evangelical Church.

Most of the mediaeval walls of the church survive, with of a mixture of magnesian limestone, reused Roman gritstone blocks and brick infill. The chancel has one original window, and the nave has two. The chancel arch survived, blocked, and there is the lowest stage of a wooden bell turret, now inside the roof.

Friends’ Meeting House in Friargate is one of three Quaker meeting houses in York (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Today’s Prayer (Saturday 8 October 2022):

The Collect:

O Lord, we beseech you mercifully to hear the prayers

of your people who call upon you;

and grant that they may both perceive and know

what things they ought to do,

and also may have grace and power faithfully to fulfil them;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

The Post Communion Prayer:

Almighty God,

you have taught us through your Son

that love is the fulfilling of the law:

grant that we may love you with our whole heart

and our neighbours as ourselves;

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

The theme in the USPG Prayer Diary this week has been ‘Mission in a Crisis.’ This theme was introduced on Sunday by Father Rasika Abeysinghe, Priest in the Diocese of Kurunagala, Church of Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

The USPG Prayer Diary invites us to pray today in these words:

We pray for church institutions which are still recovering from the Covid pandemic. May we recognise that different countries are facing different challenges related to the pandemic.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

York Baptist Church on Priory Street opened in 1868 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

‘Take a Pew’ … a rainbow-coloured bench in front of York Unitarian Church (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)