Patrick Comerford)

The Jewish New Year 5783, Rosh haShanah, began last Sunday night (25 September), when two of us were guests in the Milton Keynes and District Reform Synagogue, and Yom Kippur this year is on 5 October, beginning on Tuesday evening (4 October) with Kol Nidre.

This evening marks the beginning of the Shabbat between Rosh haShanah and Yom Kippur, and is known as Shabbat Shuvah (שבת שובה), the ‘Shabbat of Return’, or Shabbat Teshuvah (שבת תשובה), the ‘Sabbath of Repentance.’

This is one of the Ten Days of Repentance. The name derives from the Haftarah or reading from the prophets for this Shabbat, which opens with the words, ‘Return O Israel unto the Lord your God’ (Hosea 14: 1).

The word shuvah and the word teshuvah share a common root. Teshuvah or repentance is a core concept of the High Holidays. The word literally means ‘return.’ Services on Shabbat Shuvah are typically solemn and focused, and the Haftarah portion deals with themes of repentance and forgiveness.

Sephardic Jews read Hosea 14: 2-10 and Micah 7: 18-20, while Ashkenazi Jews read Hosea 14: 2-10 and Joel 2: 15-27. The selection from Hosea focuses on a universal call for repentance and an assurance that those who return to God will benefit from divine healing and restoration. Hosea focuses on divine forgiveness and how great it is in comparison to the forgiveness of humanity. The selection from Joel imagines a blow of the shofar that unites the people in fasting and supplication.

Along with Shabbat Hagadol, the Shabbat preceding Passover, this is one of the two times a year when it is customary for rabbis to deliver longer than usual addresses on timely topics, emphasising the severity of transgression so that people turn their hearts toward repentance. These sermons on Shabbat Shuvah traditionally focus on the themes of repentance, prayer and charity.

The traditional prayer Avinu Malkeinu (אָבִינוּ מַלְכֵּנוּ, ‘Our Father, Our King’) is recited throughout the Ten Days of Repentance, from Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur inclusive.

This prayer has been described as ‘the oldest and most moving of all the litanies of the Jewish Year.’ It refers to God as both ‘Our Father’ (Isaiah 63: 16) and ‘Our King’ (Isaiah 33: 22). Each line of the prayer begins with the words ‘Avinu Malkeinu’ (‘Our Father, Our King’), followed by phrases, prayers or petitions.

The prayer book Service of the Heart offers this responsive reading for the Sabbath of Repentance:

When heavy burdens oppress us, and our spirit grows faint with us, and the gloom of failure settles on us,

Give us strength, O Lord, and the vision to see through the darkness to the light beyond.

When doubts assail us concerning your justice, and when we question the value of our earthly life, because suffering hides you from our vision,

Give us faith, O Lord, and the strength to bear pain without complaint, and the patience to await a deeper insight into your purposes.

When, through self-indulgence, or from a blind following of the multitude, or by suppression of the voice of conscience, our sense of duty grows dim, and we call evil good and good evil,

Give us discernment, O Lord, and a heart more awake to the rights of others, and a spirit more responsive to their needs.

When, because we are immersed in material cares, or in the eager pursuit of worldly aims and pleasures, the thought of you fades out of our consciousness,

Let all things witness to you, O Lord, and let them lead us back into your presence.

The master Kabbalist Rabbi Isaac Luria the Arizal taught that the seven days between Rosh haShanah and Yom Kippur – which always include one Sunday, one Monday, and so on – correspond to the seven days of the week, each day representing all the corresponding days of the year: the Sunday embodies all Sundays; the Monday embodies all Mondays, and so on. These days are days to use wisely.

Meanwhile, this weekend, in what is described as a ‘Reverse Tashlich’, members of the Jewish community in Milton Keynes are taking part in a litter pick on Sunday. Several synagogues around the world are doing similar activities this weekend, as a ‘Reverse Tashlich’.

Traditionally with tashlich, people empty their pockets into a stream or lake, to symbolise throwing away their sins. This weekend, instead of throwing things, people are being invited to pick up rubbish, doing some Tikkun Olam - to make the world a better place.

Shabbat Shalom

30 September 2022

Praying in Ordinary Time with USPG:

Friday 30 September 2022

Saint Olave’s Church, Marygate, York … known for its liberal Catholic tradition of liturgy, music, prayer, theological understanding and preaching (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Patrick Comerford

In the Calendar in Common Worship, the Church of England today (30 September 2022) commemorates Jerome (420), Translator of the Scriptures, Teacher of the Faith. Today is also an Ember Day.

Before today gets busy, I am taking some time this morning for reading, prayer and reflection.

This morning, and throughout this week and next, I am reflecting each morning on a church, chapel, or place of worship in York, where I stayed earlier this month.

In my prayer diary this week I am reflecting in these ways:

1, One of the readings for the morning;

2, Reflecting on a church, chapel or place of worship in York;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary, ‘Pray with the World Church.’

The ruined nave of Saint Mary’s Abbey Church forms the boundary of Saint Olave’s churchyard (Photograph Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Saint Jerome was born at Strido near Aquileia on the Adriatic coast of Dalmatia, ca 342. He studied at Rome, where he was baptised. He tried the life of a monk for a time, but unsuccessfully. Following a dream in which he stood before the judgment seat of God and was condemned for his faith in classics rather than Christ, he learned Hebrew to assist his study of the scriptures. This, with his skills in rhetoric and Greek, enabled him to begin his life’s work of translating the newly-canonised Bible into Latin. He eventually settled at Bethlehem, where he founded a monastery and devoted the rest of his life to study. He died on this day in the year 420.

Luke 10: 13-16 (NRSVA):

[Jesus said:] 13 ‘Woe to you, Chorazin! Woe to you, Bethsaida! For if the deeds of power done in you had been done in Tyre and Sidon, they would have repented long ago, sitting in sackcloth and ashes. 14 But at the judgement it will be more tolerable for Tyre and Sidon than for you. 15 And you, Capernaum,

will you be exalted to heaven?

No, you will be brought down to Hades.

16 ‘Whoever listens to you listens to me, and whoever rejects you rejects me, and whoever rejects me rejects the one who sent me.’

A statue of Saint Olave over the north porch … Saint Olave’s Church, Marygate, is the first church ever dedicated to Saint Olaf (Photograph Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Saint Olave’s Church, Marygate, York:

Saint Olave’s Church, Marygate, York, is the first church in the world to be dedicated to Saint Olaf, the former warrior King of Norway, who converted Norway to Christianity and was killed at the Battle of Stiklestad (Stiklarstaðir) in 1030. His cult spread rapidly throughout the Viking world.

Saint Olave’s was founded by Siward, Earl of Northumbria, who was buried there in 1055. A carved coffin lid from this period, possibly from Saint Olave’s, is in the Yorkshire Museum nearby and be from Siward’s grave.

After the Norman Conquest, Saint Olave’s was given to a group of Benedictine monks who came from the new foundation of Whitby via Lastingham. They built neighbouring Saint Mary’s Abbey, one of the greatest monasteries of mediaeval England. The ruined nave of the abbey church now forms the boundary to Saint Olave’s churchyard.

For the next 400 years, Saint Olave’s remained part of the abbey, serving the Bootham and Marygate area. The monks held the revenues previously due to Saint Olave’s as a parish church, leading to years of disputes and neglect.

The church was given parochial status in the 15th century and the parishioners were ordered to repair the building. The church was rebuilt after 1466, when Archbishop George Neville ordered repairs, and the north aisle and wall was extended, which accounts for the asymmetrical placing of the tower.

The work was finished by 1471, when the church also had a clerestory in the nave, and the tower was rebuilt between 1478 and 1487.

Following the dissolution of Saint Mary’s Abbey in 1539, Saint Olave’s remained a parish church.

During the Civil War, Charles I established his headquarters in the King’s Manor nearby. During the siege of York, the Parliamentary army set up a battery of cannons on the roof of St Olave’s, using it as a gun platform. In the bombardments of the siege in the summer of 1644, both the church and the area around Bootham and Gillygate were devastated.

The church was completely rebuilt and restored in 1720-1721, using stones from the abbey ruins, and the mediaeval clerestory was removed.

The church ended at the present chancel arch until 1887, and the different cross-section of the east columns of the nave arcade may represent this. The present chancel was built in 1887, and the 15th century glass put in the present east window. The stone corbels and stops in the chancel were left uncarved and unfinished at this time.

As part of the late Victorian restorations initiated by the Revd William Croser Hey, the 18th century whitewash was removed from the walls and columns, revealing the 1721 stonework once again.

A vestry was converted to form the Chapel of the Transfiguration in 1908, a new vestry was built on the north side of the church, and the chancel was extended.

The new sanctuary was created at the chancel steps in 1986 and a nave altar was introduced. The corbels and stops in the chancel were carved by the York sculptor Charles Gurrey in 2000-2001, completing the chancel.

The church is built of magnesium limestone in the perpendicular style. Some original mediaeval stone can be found in the tower structure. The internal monuments and memorials are largely 18th century.

The Revd Liz Hassall was licensed as Priest-in-Charge of the York City Centre Churches in Saint Olave’s on 15 December 2020. Saint Olave’s is known for its liberal Catholic tradition of liturgy, music, prayer, theological understanding and preaching. The Sung Eucharist is celebrated on Sunday mornings and major weekday festivals. The worship is formal, but with a lightness of touch.

The parish seeks to be a worshipping, learning and healing community that is non-judgmental and that offers gentleness, security and acceptance. The eclectic, diverse congregation is drawn from within the parish and a wider area of York and surrounding villages.

Inside Saint Olave’s Church, facing the east end (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Today’s Prayer (Friday 30 September 2022, Saint Jerome):

The Collect:

God, who in generous mercy sent the Holy Spirit

upon your Church in the burning fire of your love:

grant that your people may be fervent

in the fellowship of the gospel

that, always abiding in you,

they may be found steadfast in faith and active in service;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

The Post Communion Prayer:

Keep, O Lord, your Church, with your perpetual mercy;

and, because without you our human frailty cannot but fall,

keep us ever by your help from all things hurtful,

and lead us to all things profitable to our salvation;

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

The theme in the USPG prayer diary this week is ‘Celebrating 75 Years,’ which was introduced on Sunday by the Revd Davidson Solanki, USPG’s Regional Manager for Asia and the Middle East.

The USPG Prayer Diary invites us to pray today (International Translation Day) in these words:

We give thanks for those who are able to translate between languages, facilitating dialogue and building relationships between peoples of different languages.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

Inside Saint Olave’s Church, facing the west end (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

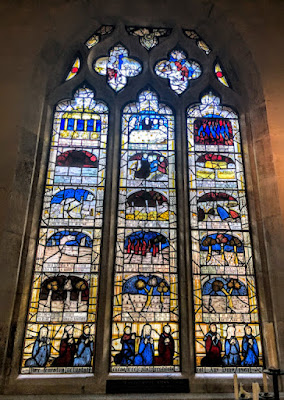

The east window in Saint Olave’s includes 15th century glass (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Patrick Comerford

In the Calendar in Common Worship, the Church of England today (30 September 2022) commemorates Jerome (420), Translator of the Scriptures, Teacher of the Faith. Today is also an Ember Day.

Before today gets busy, I am taking some time this morning for reading, prayer and reflection.

This morning, and throughout this week and next, I am reflecting each morning on a church, chapel, or place of worship in York, where I stayed earlier this month.

In my prayer diary this week I am reflecting in these ways:

1, One of the readings for the morning;

2, Reflecting on a church, chapel or place of worship in York;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary, ‘Pray with the World Church.’

The ruined nave of Saint Mary’s Abbey Church forms the boundary of Saint Olave’s churchyard (Photograph Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Saint Jerome was born at Strido near Aquileia on the Adriatic coast of Dalmatia, ca 342. He studied at Rome, where he was baptised. He tried the life of a monk for a time, but unsuccessfully. Following a dream in which he stood before the judgment seat of God and was condemned for his faith in classics rather than Christ, he learned Hebrew to assist his study of the scriptures. This, with his skills in rhetoric and Greek, enabled him to begin his life’s work of translating the newly-canonised Bible into Latin. He eventually settled at Bethlehem, where he founded a monastery and devoted the rest of his life to study. He died on this day in the year 420.

Luke 10: 13-16 (NRSVA):

[Jesus said:] 13 ‘Woe to you, Chorazin! Woe to you, Bethsaida! For if the deeds of power done in you had been done in Tyre and Sidon, they would have repented long ago, sitting in sackcloth and ashes. 14 But at the judgement it will be more tolerable for Tyre and Sidon than for you. 15 And you, Capernaum,

will you be exalted to heaven?

No, you will be brought down to Hades.

16 ‘Whoever listens to you listens to me, and whoever rejects you rejects me, and whoever rejects me rejects the one who sent me.’

A statue of Saint Olave over the north porch … Saint Olave’s Church, Marygate, is the first church ever dedicated to Saint Olaf (Photograph Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Saint Olave’s Church, Marygate, York:

Saint Olave’s Church, Marygate, York, is the first church in the world to be dedicated to Saint Olaf, the former warrior King of Norway, who converted Norway to Christianity and was killed at the Battle of Stiklestad (Stiklarstaðir) in 1030. His cult spread rapidly throughout the Viking world.

Saint Olave’s was founded by Siward, Earl of Northumbria, who was buried there in 1055. A carved coffin lid from this period, possibly from Saint Olave’s, is in the Yorkshire Museum nearby and be from Siward’s grave.

After the Norman Conquest, Saint Olave’s was given to a group of Benedictine monks who came from the new foundation of Whitby via Lastingham. They built neighbouring Saint Mary’s Abbey, one of the greatest monasteries of mediaeval England. The ruined nave of the abbey church now forms the boundary to Saint Olave’s churchyard.

For the next 400 years, Saint Olave’s remained part of the abbey, serving the Bootham and Marygate area. The monks held the revenues previously due to Saint Olave’s as a parish church, leading to years of disputes and neglect.

The church was given parochial status in the 15th century and the parishioners were ordered to repair the building. The church was rebuilt after 1466, when Archbishop George Neville ordered repairs, and the north aisle and wall was extended, which accounts for the asymmetrical placing of the tower.

The work was finished by 1471, when the church also had a clerestory in the nave, and the tower was rebuilt between 1478 and 1487.

Following the dissolution of Saint Mary’s Abbey in 1539, Saint Olave’s remained a parish church.

During the Civil War, Charles I established his headquarters in the King’s Manor nearby. During the siege of York, the Parliamentary army set up a battery of cannons on the roof of St Olave’s, using it as a gun platform. In the bombardments of the siege in the summer of 1644, both the church and the area around Bootham and Gillygate were devastated.

The church was completely rebuilt and restored in 1720-1721, using stones from the abbey ruins, and the mediaeval clerestory was removed.

The church ended at the present chancel arch until 1887, and the different cross-section of the east columns of the nave arcade may represent this. The present chancel was built in 1887, and the 15th century glass put in the present east window. The stone corbels and stops in the chancel were left uncarved and unfinished at this time.

As part of the late Victorian restorations initiated by the Revd William Croser Hey, the 18th century whitewash was removed from the walls and columns, revealing the 1721 stonework once again.

A vestry was converted to form the Chapel of the Transfiguration in 1908, a new vestry was built on the north side of the church, and the chancel was extended.

The new sanctuary was created at the chancel steps in 1986 and a nave altar was introduced. The corbels and stops in the chancel were carved by the York sculptor Charles Gurrey in 2000-2001, completing the chancel.

The church is built of magnesium limestone in the perpendicular style. Some original mediaeval stone can be found in the tower structure. The internal monuments and memorials are largely 18th century.

The Revd Liz Hassall was licensed as Priest-in-Charge of the York City Centre Churches in Saint Olave’s on 15 December 2020. Saint Olave’s is known for its liberal Catholic tradition of liturgy, music, prayer, theological understanding and preaching. The Sung Eucharist is celebrated on Sunday mornings and major weekday festivals. The worship is formal, but with a lightness of touch.

The parish seeks to be a worshipping, learning and healing community that is non-judgmental and that offers gentleness, security and acceptance. The eclectic, diverse congregation is drawn from within the parish and a wider area of York and surrounding villages.

Inside Saint Olave’s Church, facing the east end (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Today’s Prayer (Friday 30 September 2022, Saint Jerome):

The Collect:

God, who in generous mercy sent the Holy Spirit

upon your Church in the burning fire of your love:

grant that your people may be fervent

in the fellowship of the gospel

that, always abiding in you,

they may be found steadfast in faith and active in service;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

The Post Communion Prayer:

Keep, O Lord, your Church, with your perpetual mercy;

and, because without you our human frailty cannot but fall,

keep us ever by your help from all things hurtful,

and lead us to all things profitable to our salvation;

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

The theme in the USPG prayer diary this week is ‘Celebrating 75 Years,’ which was introduced on Sunday by the Revd Davidson Solanki, USPG’s Regional Manager for Asia and the Middle East.

The USPG Prayer Diary invites us to pray today (International Translation Day) in these words:

We give thanks for those who are able to translate between languages, facilitating dialogue and building relationships between peoples of different languages.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

Inside Saint Olave’s Church, facing the west end (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

The east window in Saint Olave’s includes 15th century glass (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

29 September 2022

Saint Michael the Protector

by Emily Young, Britain’s

‘greatest living stone sculptor’

‘Archangel Michael The Protector’ by Emily Young at Saint Pancras Church … today is the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Patrick Comerford

Today is the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels. During my visit to London a few days ago for a day’s events organised by the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel) to see Emily Young’s sculpture, ‘Archangel Michael The Protector,’ in the gardens of Saint Pancras Church, Euston Road.

Like many people, I never cease to be fascinated by the Caryatids that make Saint Pancras a unique and captivating church. But I wondered last weekend how people miss the opportunity to appreciate Emily Young’s ‘Archangel Michael The Protector’ in the church gardens

‘Archangel Michael The Protector’ is in onyx and can be viewed in the church grounds from Upper Woburn Place, around the corner from Euston Road.

An inscription on a plaque between the sculpture and the railings reads: ‘In memory of the victims of the 7th July 2005 bombings and all victims of violence. ‘I will lift up my eyes unto the hills’ Psalm 121.’

Nothing moves in this image, a silent reminder of what is being commemorated in the sculpture. Because Saint Michael’s face has only one eye, and this is closed, some critics have wondered whether the quotation is ill-chosen. But the full context is provided in Psalm 121: 1-2:

1 I lift up my eyes to the hills—

from where will my help come?

2 My help comes from the Lord,

who made heaven and earth.

The 7 July 2005 London bombings, often referred to as 7/7, were a series of four co-ordinated suicide attacks that targeted commuters on the public transport system in the morning rush hour.

Three homemade bombs packed into backpacks were detonated in quick succession on Underground trains on the Circle line near Aldgate and at Edgware Road, and on the Piccadilly line near Russell Square; later, a fourth bomb went off on a bus in Tavistock Square, near Upper Woburn Place and Saint Pancras Church.

Apart from the four bombers, 52 people of 18 different nationalities were killed and more than 700 were injured in the attacks. It was Britain’s deadliest terrorist incident since the 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 near Lockerbie, and the first Islamist suicide attack in the UK.

‘Tempesta,’ Clastic Igneous Rock, by Emily Young (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Emily Young has been described as ‘Britain’s foremost female stone sculptor’ and ‘Britain’s greatest living stone sculptor.’ Some years ago, as I was making my way back from the USPG offices in Southwark, I stopped and took time at an open-air exhibition at ENO Southbank of works by Emily Young.

A number of her works were forming a sculpture trail or garden at the NEO Bankside development on South Bank in ‘Emily Young: Sculptor Trail.’ The exhibition was both a continuation and a broadening of her presence on the South Bank, echoing three large-scale works on long-loan facing the Tate Modern from NEO Bankside.

Emily Young’s works are instantly recognisable and accessible. She deals in spectacular lumps of stone – quartzite, onyx, marble, alabaster – to which she gives an identity by carving a face but leaving the remainder of the rock displayed in its raw, craggy intensity, as if the face had grown or evolved organically. The Financial Times says: ‘Her sculptures meditate on time, nature, memory, man’s relationship to the Earth.’

Emily Young was born in London in 1951 into a family of writers, artists and politicians. Her grandmother, the sculptor Kathleen Scott (1878-1947), was a colleague of Auguste Rodin, and the widow of the Polar explorer, Captain Robert Falcon Scott, known as Scott of the Antarctic. Her works included a statue of Edward Smith, the captain of the Titanic, now in Beacon Park, Lichfield. She later married Emily Young’s paternal grandfather, the politician and writer Edward Hilton Young, 1st Lord Kennet.

Emily Young’s father, Wayland Hilton Young, 2nd Lord Kennet, was also a politician, conservationist and writer. Her mother was the writer and commentator Elizabeth Young; her uncle was the ornithologist, conservationist and painter, Sir Peter Scott.

She was still a student when she achieved fame (or notoriety) in 1971 as the inspiration for the Pink Floyd song See Emily Play written by Syd Barrett of Pink Floyd. But the song has earlier origins in the 1960s. She was 15 when she met Syd Barrett at the London Free School in 1965. ‘I used to go there because there were a lot of Beat philosophers and poets around,’ she said many years later. ‘There were fundraising concerts with The Pink Floyd Sound, as they were then called. I was more keen on poets than rockers. I was educating myself. I was a seeker. I wanted to meet everyone and take every drug.’

As a young woman, Emily Young worked primarily as a painter, while she was studying at Chelsea School of Art in 1968 and later at Central Saint Martins. She travelled around the world in the late 1960s and 1970s, spending time in the US, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, France, Italy, Africa, South America, the Middle East and China, encountering a variety of cultures and developing her experiences of art.

In the early 1980s, she abandoned painting and turned to carving, sourcing stone from all around the world. Travelling from a London childhood, to a European education, to a life lived as an artist round the world, she began to interact with the timeless quality of stone to produce breath-taking sculptures of luminous intensity and great beauty.

As well as marble, she carves in semi-precious stone – agate, alabaster, lapis lazuli. These not only reflect and refract the light – but glow with a passionate intensity (as Winged Golden Onyx Head), revealing the hidden crystalline structure of the material and the subtle layers the time has laid down, showing the liquid qualities of hard rock.

The primary objective of her sculpture is to bring the natural beauty and energy of stone to the fore. Her sculptures have unique characters because each stone has an individual geological history and geographical source. Her approach allows the viewer to comprehend a deep grounding across time, land and cultures. She combines traditional carving skills with technology to produce work that is both contemporary and ancient, with a unique, serious and poetic presence.

She told an interviewer: ‘I carve in stone the fierce need in millions of us to retrieve some semblance of dignity for the human race in its place on Earth. We can show ourselves to posterity as a primitive and brutal life form – that what we are best at is rapacity, greed, and wilful ignorance, and we can also show that we are creatures of great love for our whole planet, that everyone of us is a worshipper in her temple of life.’

She recently explained: ‘So my work is a kind of temple activity now, devotional; when I work a piece of stone, the mineral occlusions of the past are revealed, the layers of sediment unpeeled; I may open in one knock something that took millions of years to form: dusts settling, water dripping, forces pushing, minerals growing – material and geological revelations: the story of time on Earth shows here, sometimes startling, always beautiful.’

Emily Young now divides her time between studios in London and Italy. Her permanent installations and public collections can be seen in many places, including Saint Paul’s Churchyard, Saint Pancras Church, NEO Bankside, and the Imperial War Museum in London; La Defense, Paris; Salisbury Cathedral, Wiltshire; the Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester; and the Cloister of Madonna Dell’Orto, Venice.

After years of being feted as ‘Britain’s foremost female stone sculptor,’ the art critic of the Financial Times called her ‘Britain’s greatest living stone sculptor.’ The Daily Telegraph has written: ‘Emily Young has inherited the mantle as Britain’s greatest female stone sculptor from Dame Barbara Hepworth.’

Because Emily Young’s ‘Archangel Michael The Protector’ recalls the victims of 7/7 bombings ‘and all victims of violence,’ it seems appropriate to return to the Collect of this day which I used in my prayers and reflections this morning:

Everlasting God,

you have ordained and constituted

the ministries of angels and mortals in a wonderful order:

grant that as your holy angels always serve you in heaven,

so, at your command,

they may help and defend us on earth;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

‘Archangel Michael The Protector’ by Emily Young the gardens of Saint Pancras Church at Upper Woburn Place (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Patrick Comerford

Today is the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels. During my visit to London a few days ago for a day’s events organised by the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel) to see Emily Young’s sculpture, ‘Archangel Michael The Protector,’ in the gardens of Saint Pancras Church, Euston Road.

Like many people, I never cease to be fascinated by the Caryatids that make Saint Pancras a unique and captivating church. But I wondered last weekend how people miss the opportunity to appreciate Emily Young’s ‘Archangel Michael The Protector’ in the church gardens

‘Archangel Michael The Protector’ is in onyx and can be viewed in the church grounds from Upper Woburn Place, around the corner from Euston Road.

An inscription on a plaque between the sculpture and the railings reads: ‘In memory of the victims of the 7th July 2005 bombings and all victims of violence. ‘I will lift up my eyes unto the hills’ Psalm 121.’

Nothing moves in this image, a silent reminder of what is being commemorated in the sculpture. Because Saint Michael’s face has only one eye, and this is closed, some critics have wondered whether the quotation is ill-chosen. But the full context is provided in Psalm 121: 1-2:

1 I lift up my eyes to the hills—

from where will my help come?

2 My help comes from the Lord,

who made heaven and earth.

The 7 July 2005 London bombings, often referred to as 7/7, were a series of four co-ordinated suicide attacks that targeted commuters on the public transport system in the morning rush hour.

Three homemade bombs packed into backpacks were detonated in quick succession on Underground trains on the Circle line near Aldgate and at Edgware Road, and on the Piccadilly line near Russell Square; later, a fourth bomb went off on a bus in Tavistock Square, near Upper Woburn Place and Saint Pancras Church.

Apart from the four bombers, 52 people of 18 different nationalities were killed and more than 700 were injured in the attacks. It was Britain’s deadliest terrorist incident since the 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 near Lockerbie, and the first Islamist suicide attack in the UK.

‘Tempesta,’ Clastic Igneous Rock, by Emily Young (Photograph: Patrick Comerford)

Emily Young has been described as ‘Britain’s foremost female stone sculptor’ and ‘Britain’s greatest living stone sculptor.’ Some years ago, as I was making my way back from the USPG offices in Southwark, I stopped and took time at an open-air exhibition at ENO Southbank of works by Emily Young.

A number of her works were forming a sculpture trail or garden at the NEO Bankside development on South Bank in ‘Emily Young: Sculptor Trail.’ The exhibition was both a continuation and a broadening of her presence on the South Bank, echoing three large-scale works on long-loan facing the Tate Modern from NEO Bankside.

Emily Young’s works are instantly recognisable and accessible. She deals in spectacular lumps of stone – quartzite, onyx, marble, alabaster – to which she gives an identity by carving a face but leaving the remainder of the rock displayed in its raw, craggy intensity, as if the face had grown or evolved organically. The Financial Times says: ‘Her sculptures meditate on time, nature, memory, man’s relationship to the Earth.’

Emily Young was born in London in 1951 into a family of writers, artists and politicians. Her grandmother, the sculptor Kathleen Scott (1878-1947), was a colleague of Auguste Rodin, and the widow of the Polar explorer, Captain Robert Falcon Scott, known as Scott of the Antarctic. Her works included a statue of Edward Smith, the captain of the Titanic, now in Beacon Park, Lichfield. She later married Emily Young’s paternal grandfather, the politician and writer Edward Hilton Young, 1st Lord Kennet.

Emily Young’s father, Wayland Hilton Young, 2nd Lord Kennet, was also a politician, conservationist and writer. Her mother was the writer and commentator Elizabeth Young; her uncle was the ornithologist, conservationist and painter, Sir Peter Scott.

She was still a student when she achieved fame (or notoriety) in 1971 as the inspiration for the Pink Floyd song See Emily Play written by Syd Barrett of Pink Floyd. But the song has earlier origins in the 1960s. She was 15 when she met Syd Barrett at the London Free School in 1965. ‘I used to go there because there were a lot of Beat philosophers and poets around,’ she said many years later. ‘There were fundraising concerts with The Pink Floyd Sound, as they were then called. I was more keen on poets than rockers. I was educating myself. I was a seeker. I wanted to meet everyone and take every drug.’

As a young woman, Emily Young worked primarily as a painter, while she was studying at Chelsea School of Art in 1968 and later at Central Saint Martins. She travelled around the world in the late 1960s and 1970s, spending time in the US, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, France, Italy, Africa, South America, the Middle East and China, encountering a variety of cultures and developing her experiences of art.

In the early 1980s, she abandoned painting and turned to carving, sourcing stone from all around the world. Travelling from a London childhood, to a European education, to a life lived as an artist round the world, she began to interact with the timeless quality of stone to produce breath-taking sculptures of luminous intensity and great beauty.

As well as marble, she carves in semi-precious stone – agate, alabaster, lapis lazuli. These not only reflect and refract the light – but glow with a passionate intensity (as Winged Golden Onyx Head), revealing the hidden crystalline structure of the material and the subtle layers the time has laid down, showing the liquid qualities of hard rock.

The primary objective of her sculpture is to bring the natural beauty and energy of stone to the fore. Her sculptures have unique characters because each stone has an individual geological history and geographical source. Her approach allows the viewer to comprehend a deep grounding across time, land and cultures. She combines traditional carving skills with technology to produce work that is both contemporary and ancient, with a unique, serious and poetic presence.

She told an interviewer: ‘I carve in stone the fierce need in millions of us to retrieve some semblance of dignity for the human race in its place on Earth. We can show ourselves to posterity as a primitive and brutal life form – that what we are best at is rapacity, greed, and wilful ignorance, and we can also show that we are creatures of great love for our whole planet, that everyone of us is a worshipper in her temple of life.’

She recently explained: ‘So my work is a kind of temple activity now, devotional; when I work a piece of stone, the mineral occlusions of the past are revealed, the layers of sediment unpeeled; I may open in one knock something that took millions of years to form: dusts settling, water dripping, forces pushing, minerals growing – material and geological revelations: the story of time on Earth shows here, sometimes startling, always beautiful.’

Emily Young now divides her time between studios in London and Italy. Her permanent installations and public collections can be seen in many places, including Saint Paul’s Churchyard, Saint Pancras Church, NEO Bankside, and the Imperial War Museum in London; La Defense, Paris; Salisbury Cathedral, Wiltshire; the Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester; and the Cloister of Madonna Dell’Orto, Venice.

After years of being feted as ‘Britain’s foremost female stone sculptor,’ the art critic of the Financial Times called her ‘Britain’s greatest living stone sculptor.’ The Daily Telegraph has written: ‘Emily Young has inherited the mantle as Britain’s greatest female stone sculptor from Dame Barbara Hepworth.’

Because Emily Young’s ‘Archangel Michael The Protector’ recalls the victims of 7/7 bombings ‘and all victims of violence,’ it seems appropriate to return to the Collect of this day which I used in my prayers and reflections this morning:

Everlasting God,

you have ordained and constituted

the ministries of angels and mortals in a wonderful order:

grant that as your holy angels always serve you in heaven,

so, at your command,

they may help and defend us on earth;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

‘Archangel Michael The Protector’ by Emily Young the gardens of Saint Pancras Church at Upper Woburn Place (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Praying in Ordinary Time with USPG:

Thursday 29 September 2022

Saint Michael le Belfrey Church in York stands in the shadow of York Minster ... today is the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Patrick Comerford

In the Calendar of the Church, today (29 September 2022) is the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels.

Before today gets busy, I am taking some time this morning for reading, prayer and reflection.

This morning, and throughout this week and next, I am reflecting each morning on a church, chapel, or place of worship in York, where I stayed earlier this month after a surgical procedure in Sheffield.

In my prayer diary this week I am reflecting in these ways:

1, One of the readings for the morning;

2, Reflecting on a church, chapel or place of worship in York;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary, ‘Pray with the World Church.’

Inside Saint Michael le Belfrey Church, York, facing east (Photograph Patrick Comerford, 2022)

John 1: 47-51 (NRSVA):

47 When Jesus saw Nathanael coming towards him, he said of him, ‘Here is truly an Israelite in whom there is no deceit!’ 48 Nathanael asked him, ‘Where did you come to know me?’ Jesus answered, ‘I saw you under the fig tree before Philip called you.’ 49 Nathanael replied, ‘Rabbi, you are the Son of God! You are the King of Israel!’ 50 Jesus answered, ‘Do you believe because I told you that I saw you under the fig tree? You will see greater things than these.’ 51 And he said to him, ‘Very truly, I tell you, you will see heaven opened and the angels of God ascending and descending upon the Son of Man.’

Inside Saint Michael le Belfrey Church, York, facing west (Photograph Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Saint Michael le Belfrey Church, York:

Saint Michael le Belfrey Church in York stands in the shadow of York Minster, at the junction of High Petergate and Minster Yard in the city centre, and is known as a centre of the charismatic revival. The church takes its name from the Minster Belfrey that stood on the site before the church was built.

The church is near the place where Constantine was proclaimed the Roman Emperor. An early church on the site dated back to at least 1294. But this earlier mediaeval church was so badly maintained that parishioners were afraid to enter the building for services.

The present church was built between 1525 and 1537, under the direction of the master mason to the Minster, John Forman. Saint Michael-le-Belfrey is the only church in York to have been built in the 16th century and it is the largest pre-Reformation parish church in the city.

Saint Michael’s has one of the most notable collections of mid-16th century glass in any English parish church. The east window contains a large collection of glass from about 1330, that came from the demolished predecessor of this church.

The east window includes a depiction of the martyrdom of Saint Thomas Becket and there are four panels depicting the life of Gilbert, Thomas Becket’s father. This is a rare survival as Henry VIII ordered all images of Saint Thomas to be destroyed in 1538, and Thomas’s name to be removed from the English church calendar.

Guy Fawkes was baptised in the church on 16 April 1570. He later became a Roman Catholic, and was part of the failed Gunpowder Plot in 1605.

The reredos and altar rails were designed by John Etty and completed by his son, William, in 1712. The gallery was added in 1785.

The stained glass panels on the front of the building were restored by John Knowles in the early 19th century. The west front and bellcote date from 1867 and were supervised by the architect George Fowler Jones.

In the early 1970s, the parish of Saint Michael le Belfrey was joined with nearby Saint Cuthbert’s, which had experienced revival in the late 1960s under the leadership of David Watson and could no longer be accommodated in the building. Growth continued in the 1970s and the church became known as a centre for charismatic renewal.

• The incumbent is the Revd Matthew Porter. The church continues to reflect the legacy of David Watson. There are usually three Sunday services: a more formal morning service at 9 am; the XI, a family service at 11 am; and ‘The6’, an evening service with an informal style. The ‘Faith in the City’ service is at 12:30 on Wednesday lunch-times. A daughter church, G2, meets twice on Sundays at Central Methodist Church, York.

The reredos and altar rails in Saint Michael le Belfrey Church, York, were designed by John Etty and completed by his son, William, in 1712 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Today’s Prayer (Thursday 29 September 2022, Saint Michael and All Angels):

The Collect:

Everlasting God,

you have ordained and constituted

the ministries of angels and mortals in a wonderful order:

grant that as your holy angels always serve you in heaven,

so, at your command,

they may help and defend us on earth;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

The Post Communion Prayer:

Lord of heaven,

in this eucharist you have brought us near

to an innumerable company of angels

and to the spirits of the saints made perfect:

as in this food of our earthly pilgrimage

we have shared their fellowship,

so may we come to share their joy in heaven;

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

The theme in the USPG prayer diary this week is ‘Celebrating 75 Years,’ which was introduced on Sunday by the Revd Davidson Solanki, USPG’s Regional Manager for Asia and the Middle East.

The USPG Prayer Diary invites us to pray today in these words:

Almighty God, may good triumph over evil. Let us be courageous in our pursuit of justice and bold in our faith.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

Saint Michael le Belfrey has a notable collections of stained-glass windows (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

The church was built between 1525 and 1537, under the direction of the master mason to the Minster, John Forman (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Patrick Comerford

In the Calendar of the Church, today (29 September 2022) is the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels.

Before today gets busy, I am taking some time this morning for reading, prayer and reflection.

This morning, and throughout this week and next, I am reflecting each morning on a church, chapel, or place of worship in York, where I stayed earlier this month after a surgical procedure in Sheffield.

In my prayer diary this week I am reflecting in these ways:

1, One of the readings for the morning;

2, Reflecting on a church, chapel or place of worship in York;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary, ‘Pray with the World Church.’

Inside Saint Michael le Belfrey Church, York, facing east (Photograph Patrick Comerford, 2022)

John 1: 47-51 (NRSVA):

47 When Jesus saw Nathanael coming towards him, he said of him, ‘Here is truly an Israelite in whom there is no deceit!’ 48 Nathanael asked him, ‘Where did you come to know me?’ Jesus answered, ‘I saw you under the fig tree before Philip called you.’ 49 Nathanael replied, ‘Rabbi, you are the Son of God! You are the King of Israel!’ 50 Jesus answered, ‘Do you believe because I told you that I saw you under the fig tree? You will see greater things than these.’ 51 And he said to him, ‘Very truly, I tell you, you will see heaven opened and the angels of God ascending and descending upon the Son of Man.’

Inside Saint Michael le Belfrey Church, York, facing west (Photograph Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Saint Michael le Belfrey Church, York:

Saint Michael le Belfrey Church in York stands in the shadow of York Minster, at the junction of High Petergate and Minster Yard in the city centre, and is known as a centre of the charismatic revival. The church takes its name from the Minster Belfrey that stood on the site before the church was built.

The church is near the place where Constantine was proclaimed the Roman Emperor. An early church on the site dated back to at least 1294. But this earlier mediaeval church was so badly maintained that parishioners were afraid to enter the building for services.

The present church was built between 1525 and 1537, under the direction of the master mason to the Minster, John Forman. Saint Michael-le-Belfrey is the only church in York to have been built in the 16th century and it is the largest pre-Reformation parish church in the city.

Saint Michael’s has one of the most notable collections of mid-16th century glass in any English parish church. The east window contains a large collection of glass from about 1330, that came from the demolished predecessor of this church.

The east window includes a depiction of the martyrdom of Saint Thomas Becket and there are four panels depicting the life of Gilbert, Thomas Becket’s father. This is a rare survival as Henry VIII ordered all images of Saint Thomas to be destroyed in 1538, and Thomas’s name to be removed from the English church calendar.

Guy Fawkes was baptised in the church on 16 April 1570. He later became a Roman Catholic, and was part of the failed Gunpowder Plot in 1605.

The reredos and altar rails were designed by John Etty and completed by his son, William, in 1712. The gallery was added in 1785.

The stained glass panels on the front of the building were restored by John Knowles in the early 19th century. The west front and bellcote date from 1867 and were supervised by the architect George Fowler Jones.

In the early 1970s, the parish of Saint Michael le Belfrey was joined with nearby Saint Cuthbert’s, which had experienced revival in the late 1960s under the leadership of David Watson and could no longer be accommodated in the building. Growth continued in the 1970s and the church became known as a centre for charismatic renewal.

• The incumbent is the Revd Matthew Porter. The church continues to reflect the legacy of David Watson. There are usually three Sunday services: a more formal morning service at 9 am; the XI, a family service at 11 am; and ‘The6’, an evening service with an informal style. The ‘Faith in the City’ service is at 12:30 on Wednesday lunch-times. A daughter church, G2, meets twice on Sundays at Central Methodist Church, York.

The reredos and altar rails in Saint Michael le Belfrey Church, York, were designed by John Etty and completed by his son, William, in 1712 (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Today’s Prayer (Thursday 29 September 2022, Saint Michael and All Angels):

The Collect:

Everlasting God,

you have ordained and constituted

the ministries of angels and mortals in a wonderful order:

grant that as your holy angels always serve you in heaven,

so, at your command,

they may help and defend us on earth;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

The Post Communion Prayer:

Lord of heaven,

in this eucharist you have brought us near

to an innumerable company of angels

and to the spirits of the saints made perfect:

as in this food of our earthly pilgrimage

we have shared their fellowship,

so may we come to share their joy in heaven;

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

The theme in the USPG prayer diary this week is ‘Celebrating 75 Years,’ which was introduced on Sunday by the Revd Davidson Solanki, USPG’s Regional Manager for Asia and the Middle East.

The USPG Prayer Diary invites us to pray today in these words:

Almighty God, may good triumph over evil. Let us be courageous in our pursuit of justice and bold in our faith.

Yesterday’s reflection

Continued tomorrow

Saint Michael le Belfrey has a notable collections of stained-glass windows (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Anglicised Edition copyright © 1989, 1995, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. http://nrsvbibles.org

The church was built between 1525 and 1537, under the direction of the master mason to the Minster, John Forman (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

28 September 2022

Holy Trinity Sloane Square is

John Betjeman’s ‘Cathedral of

the Arts and Crafts Movement’

Part of the Edward Burne-Jones East Window in Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Square, London (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Patrick Comerford

I was in London last weekend for the annual reunion of the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel). We were invited to a celebration of the Eucharist in Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Square, followed by lunch and short presentations by USPG staff.

Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Square, is right at the heart of London. The former Poet Laureate, Sir John Betjeman, described Holy Trinity Church in Chelsea as the ‘Cathedral of the Arts and Crafts Movement’, referring to treasures and glass by William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones and many others.

Holy Trinity Sloane Square is in the Catholic tradition in the Church of England, and says on its website and materials ‘The world will be saved by beauty’, a quotation from The Fool by Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Square, was described by John Betjeman as the ‘Cathedral of the Arts and Crafts Movement’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Holy Trinity is one of the few churches in these islands that can be regarded as what the Germans describe as a gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art. Behind the magnificent red brick and stone façade, reminiscent of collegiate architecture of the late 16th and early 17th century, is truly a jewel-box of the best stained glass, sculpture and highly wrought metalwork created by many of the finest artists and craftsmen of the late 19th century.

The first church on the site was a Gothic building from 1828-1830, designed by James Savage and built in brick with stone dressings. The west front, towards the street, had an entrance flanked by octagonal turrets topped with spires.

It was originally intended as chapel of ease to the new parish church of Saint Luke, but was given its own parish, sometimes known as Upper Chelsea, in 1831. It could seat 1,450 in 1838 and 1,600 in 1881.

Inside Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Square, facing east (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

George Henry Cadogan (1840-1915), 5th Earl Cadogan, and his wife, the former Lady Beatrix Craven, decided to replace the earlier church building which was part of their London estate. The old church was closed and demolished in 1888, and a temporary iron church with seating for 800 was provided in Symons Street while the new church was built.

The Cadogans chose John Dando Sedding (1838-1891) as the architect. He was one of the prime movers in the Arts and Crafts Movement, which was inspired at an early stage by AWN Pugin and John Ruskin.

At the Liverpool Art Congress in 1888, in a roll-call of the great architects and designers of his day, Sedding declared, ‘We should have had no Morris, no Burges, no Shaw, no Webb, no Bodley, no Rossetti, no Crane, but for Pugin.’

While he was still in his teens, Sedding was influenced by Ruskin and his Stones of Venice (1853). He trained as an architect in the offices of GE Street (1824-1881), the prolific and influential church architect. Other key figures in the Arts and Crafts Movement, including William Morris, Philip Webb and Norman Shaw, had also trained in Street’s offices.

Inside Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Square, facing west (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Holy Trinity Church was built in 1888-1890 on the south-east side of Sloane Street and was paid for by Lord Cadogan.

Sedding’s church was not the longest church in London, but it was the widest, exceeding Saint Paul’s Cathedral by 23 cm (9 inches). The internal fittings were the work of leading sculptors and designers of the day, including FW Pomeroy, HH Armstead, Onslow Ford and Hamo Thornycroft. Sedding died in 1891, and his memorial is on the north wall in the Lady Chapel.

Sedding died two years after Lady Cadogan laid the foundation stone of the church. His chief assistant, Henry Wilson (1864-1934), took charge of the project to complete the interior decoration of the church to Sedding’s original design.

The great East Window by Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris is the largest window ever made by William Morris & Company (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

The main structure is as Sedding designed it, but the street railings and much of the interior fittings and decoration were inspired or designed by Wilson, including the font, the Lady Chapel, the Byzantine-inspired metal screen and the bronze angels that flank the entrance to the Memorial Chapel. However, Sedding’s original conception was never fully completed.

The first thing that impresses visitors is the wealth of stained glass, particularly the great east window by Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) and William Morris (1834-1896), the largest window ever made by William Morris & Company.

Burne-Jones first contemplated a window with ‘thousands of bright little figures.’ This idea became 48 Prophets, Apostles and Saints in three columns of four rows that make up the bottom half of the window.

There are impressive windows in the north and south aisles, three by Sir William Blake Richmond (1842-1921) and two by Christopher Whall (1849-1924), and by James Powell and Sons in the Memorial Chapel.

The large west window, which Morris and Burne-Jones planned to complete before moving onto the east window, but this never happened. Its plain glass was destroyed during World War II, although all the other windows survived or were repaired.

The pulpit was designed by Seddling in the Sienna Renaissance style and is made of marble of different colours (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

The range of sculptures includes FW Pomeroy’s bronze angels and sculptured reliefs. There are works of other major sculptors too, including Onslow Ford, Frank Boucher, HH Armstead, Harry Bates and John Tweed, who carved the marble reredos in 1901.

A wealth of different marbles is employed, especially on the pulpit and in the Lady Chapel, while the bowl of the Font is made of one piece of Mexican Onyx.

The processional cross is a reproduction of the 12th century Celtic Cross of Cong.

The Sedding Altar Frontal and busts of William Morris and John Ruskin (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

The Sedding Altar Frontal, originally intended for use in Advent and Lent, was designed by Sedding and embroidered by his wife Rose.

Sedding believed that nature was the source of all true art. He always sought to find his inspiration in hedgerows and cottage gardens, especially those in Somerset, Devon and Cornwall. He also had a deep love of mediaeval embroidery, a passion he shared with his wife.

The emblems in the panel of the frontal alternate between symbols of Christ’s passion, and human images of holy devotion: Prophets and Saints.

Above the display case with the frontal are busts of William Morris and John Ruskin.

The Altar frontal of the entombment was carved by Harry Bates; the reredos was carved by John Tweed; the altar candlesticks are copies of Michelangelo’s originals in San Lorenzo Church, Florence (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

The churchmanship when the new church opened might be described as eclectically high, as the liturgy seems to have been drawn from a number of sources and traditions.

The church soon attracted the attention of Bohemian artists and poets some of whom clustered loosely round Oscar Wilde, who was arrested nearby in the Cadogan Hotel on Sloane Street. Many notable figures have been parishioners, including the Liberal politicians WE Gladstone and Sir Charles Dilke. Dilke lived on Sloane Street; his promising political career was destroyed by a well-publicised divorce case in the 1880s.

The interior was whitened by the third architect of Holy Trinity FC Eden in the 1920s, lightening the character and feel of the building considerably. The south chapel was remodelled to become the Memorial Chapel with Eden’s crucifix painted by Egerton Cooper, and the panelling inscribed with the names of parishioners who died in World War I. The War Memorial is in Sloane Square and on Remembrance Sunday clergy, choir and congregation process from the church to Sloane Square.

The central North Wall window by Sir William Blake-Richmond with the theme of Youth and its sacrifice and joys (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

The church was very popular in the 1920s with a very extensive clergy team under the rector, the Revd Christopher Cheshire (1924-1945). For a time, the liturgist and hymn writer Percy Dearmer, who collaborated closely with Ralph Vaughan Williams, was associated the church.

During World War II, the church was hit by several incendiary bombs, one at least bursting in the nave, causing considerable damage.

It took several decades of work to carry out post-war repairs and the church was closed except for Sunday matins. There was pressure to demolish rather than restore the building, and it was saved only by a vigorous campaign mounted by the Victorian Society and Sir John Betjeman who wrote in verse:

Bishop, archdeacon, rector, wardens, mayor

Guardians of Chelsea’s noblest house of prayer.

You your church’s vastness deplore

‘Should we not sell and give it to the poor?’

Recall, despite your practical suggestion

Which the disciple was who asked that question.

Betjeman said the central North Wall window by Sir William Blake-Richmond, with the theme of Youth and its sacrifice and joys, was ‘symbolising the hope that this great city may rise to the value of beauty, setting aside money and society as chief aims of life.’ Needless to say, Betjeman’s ‘noblest house of prayer’ was saved.

Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Square, was described by Sir John Betjeman as ‘Chelsea’s noblest house of prayer’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

After a long period of less symbolic worship, notably when the Revd Alfred Basil Carver was Rector (1945-1980) and the shorter incumbencies of the Revd Phillip Roberts (1980-1987) and the Revd Keith Yates (1987–1997), the church has returned to a liberal Catholic style of worship and liturgy.

The church now has a thriving congregation built when Bishop Michael Eric Marshall, former Bishop of Woolwich, was Rector (1997-2007). The connection with the world of the fine arts continued under the Revd Rob Gillion was Rector (2008-2014). He later became Bishop of Riverina in western New South Wales.

Holy Trinity has enjoyed a reputation for church music since its early days. John Sedding, also an organist, provided an unusually large chamber for the noted four-manual Walker organ. Notable organists have included Edwin Lemare (1892-1895), Sir Walter Alcock (1895-1902), John Ireland (sub organist, 1896-1904), and HL Balfour (1902-1942).

The organ was badly damaged in World War II, but was repaired in 1947 and partially rebuilt in 1967. Harrison & Harrison completed a rebuild in 2012, using the surviving Walker pipework and matching new material. The organ has 71 speaking stops and about 4,200 pipes, and remains one of the principal organs in London.

The relief panel on the west wall behind the font is to the design of Henry Wilson (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Today, the church sees itself as a ‘Shrine and Sanctuary’ for Sloane Square, and, for example, also provides chaplaincies to neighbouring places such as Harrods and the Royal Court Theatre. The parish of Saint Saviour, Upper Chelsea, was added to Holy Trinity in 2011.

Canon Nicholas Wheeler is the Rector of Holy Trinity and Saint Saviour. He returned to London from Brazil where he worked with USPG in the Parish of Christ the King in Rio de Janeiro and as a canon of the Cathedral of the Redeemer. His work in Cidade de Deus, one of the most disadvantaged communities in Rio, inspired the 2002 film, City of God.

Before going to Brazil with USPG, he spent 21 years in the Diocese of London, where his posts included Team Rector at Old Saint Pancras.

The Sung Eucharist is celebrated in Holy Trinity Church every Sunday at 11 a.m.

Holy Trinity sees itself as a ‘Shrine and Sanctuary’ for Sloane Square (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Patrick Comerford

I was in London last weekend for the annual reunion of the Anglican mission agency USPG (United Society Partners in the Gospel). We were invited to a celebration of the Eucharist in Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Square, followed by lunch and short presentations by USPG staff.

Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Square, is right at the heart of London. The former Poet Laureate, Sir John Betjeman, described Holy Trinity Church in Chelsea as the ‘Cathedral of the Arts and Crafts Movement’, referring to treasures and glass by William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones and many others.

Holy Trinity Sloane Square is in the Catholic tradition in the Church of England, and says on its website and materials ‘The world will be saved by beauty’, a quotation from The Fool by Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Square, was described by John Betjeman as the ‘Cathedral of the Arts and Crafts Movement’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Holy Trinity is one of the few churches in these islands that can be regarded as what the Germans describe as a gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art. Behind the magnificent red brick and stone façade, reminiscent of collegiate architecture of the late 16th and early 17th century, is truly a jewel-box of the best stained glass, sculpture and highly wrought metalwork created by many of the finest artists and craftsmen of the late 19th century.

The first church on the site was a Gothic building from 1828-1830, designed by James Savage and built in brick with stone dressings. The west front, towards the street, had an entrance flanked by octagonal turrets topped with spires.

It was originally intended as chapel of ease to the new parish church of Saint Luke, but was given its own parish, sometimes known as Upper Chelsea, in 1831. It could seat 1,450 in 1838 and 1,600 in 1881.

Inside Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Square, facing east (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

George Henry Cadogan (1840-1915), 5th Earl Cadogan, and his wife, the former Lady Beatrix Craven, decided to replace the earlier church building which was part of their London estate. The old church was closed and demolished in 1888, and a temporary iron church with seating for 800 was provided in Symons Street while the new church was built.

The Cadogans chose John Dando Sedding (1838-1891) as the architect. He was one of the prime movers in the Arts and Crafts Movement, which was inspired at an early stage by AWN Pugin and John Ruskin.

At the Liverpool Art Congress in 1888, in a roll-call of the great architects and designers of his day, Sedding declared, ‘We should have had no Morris, no Burges, no Shaw, no Webb, no Bodley, no Rossetti, no Crane, but for Pugin.’

While he was still in his teens, Sedding was influenced by Ruskin and his Stones of Venice (1853). He trained as an architect in the offices of GE Street (1824-1881), the prolific and influential church architect. Other key figures in the Arts and Crafts Movement, including William Morris, Philip Webb and Norman Shaw, had also trained in Street’s offices.

Inside Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Square, facing west (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Holy Trinity Church was built in 1888-1890 on the south-east side of Sloane Street and was paid for by Lord Cadogan.

Sedding’s church was not the longest church in London, but it was the widest, exceeding Saint Paul’s Cathedral by 23 cm (9 inches). The internal fittings were the work of leading sculptors and designers of the day, including FW Pomeroy, HH Armstead, Onslow Ford and Hamo Thornycroft. Sedding died in 1891, and his memorial is on the north wall in the Lady Chapel.

Sedding died two years after Lady Cadogan laid the foundation stone of the church. His chief assistant, Henry Wilson (1864-1934), took charge of the project to complete the interior decoration of the church to Sedding’s original design.

The great East Window by Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris is the largest window ever made by William Morris & Company (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

The main structure is as Sedding designed it, but the street railings and much of the interior fittings and decoration were inspired or designed by Wilson, including the font, the Lady Chapel, the Byzantine-inspired metal screen and the bronze angels that flank the entrance to the Memorial Chapel. However, Sedding’s original conception was never fully completed.

The first thing that impresses visitors is the wealth of stained glass, particularly the great east window by Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) and William Morris (1834-1896), the largest window ever made by William Morris & Company.

Burne-Jones first contemplated a window with ‘thousands of bright little figures.’ This idea became 48 Prophets, Apostles and Saints in three columns of four rows that make up the bottom half of the window.

There are impressive windows in the north and south aisles, three by Sir William Blake Richmond (1842-1921) and two by Christopher Whall (1849-1924), and by James Powell and Sons in the Memorial Chapel.

The large west window, which Morris and Burne-Jones planned to complete before moving onto the east window, but this never happened. Its plain glass was destroyed during World War II, although all the other windows survived or were repaired.

The pulpit was designed by Seddling in the Sienna Renaissance style and is made of marble of different colours (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

The range of sculptures includes FW Pomeroy’s bronze angels and sculptured reliefs. There are works of other major sculptors too, including Onslow Ford, Frank Boucher, HH Armstead, Harry Bates and John Tweed, who carved the marble reredos in 1901.

A wealth of different marbles is employed, especially on the pulpit and in the Lady Chapel, while the bowl of the Font is made of one piece of Mexican Onyx.

The processional cross is a reproduction of the 12th century Celtic Cross of Cong.

The Sedding Altar Frontal and busts of William Morris and John Ruskin (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

The Sedding Altar Frontal, originally intended for use in Advent and Lent, was designed by Sedding and embroidered by his wife Rose.

Sedding believed that nature was the source of all true art. He always sought to find his inspiration in hedgerows and cottage gardens, especially those in Somerset, Devon and Cornwall. He also had a deep love of mediaeval embroidery, a passion he shared with his wife.

The emblems in the panel of the frontal alternate between symbols of Christ’s passion, and human images of holy devotion: Prophets and Saints.

Above the display case with the frontal are busts of William Morris and John Ruskin.

The Altar frontal of the entombment was carved by Harry Bates; the reredos was carved by John Tweed; the altar candlesticks are copies of Michelangelo’s originals in San Lorenzo Church, Florence (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

The churchmanship when the new church opened might be described as eclectically high, as the liturgy seems to have been drawn from a number of sources and traditions.

The church soon attracted the attention of Bohemian artists and poets some of whom clustered loosely round Oscar Wilde, who was arrested nearby in the Cadogan Hotel on Sloane Street. Many notable figures have been parishioners, including the Liberal politicians WE Gladstone and Sir Charles Dilke. Dilke lived on Sloane Street; his promising political career was destroyed by a well-publicised divorce case in the 1880s.

The interior was whitened by the third architect of Holy Trinity FC Eden in the 1920s, lightening the character and feel of the building considerably. The south chapel was remodelled to become the Memorial Chapel with Eden’s crucifix painted by Egerton Cooper, and the panelling inscribed with the names of parishioners who died in World War I. The War Memorial is in Sloane Square and on Remembrance Sunday clergy, choir and congregation process from the church to Sloane Square.

The central North Wall window by Sir William Blake-Richmond with the theme of Youth and its sacrifice and joys (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

The church was very popular in the 1920s with a very extensive clergy team under the rector, the Revd Christopher Cheshire (1924-1945). For a time, the liturgist and hymn writer Percy Dearmer, who collaborated closely with Ralph Vaughan Williams, was associated the church.

During World War II, the church was hit by several incendiary bombs, one at least bursting in the nave, causing considerable damage.

It took several decades of work to carry out post-war repairs and the church was closed except for Sunday matins. There was pressure to demolish rather than restore the building, and it was saved only by a vigorous campaign mounted by the Victorian Society and Sir John Betjeman who wrote in verse:

Bishop, archdeacon, rector, wardens, mayor

Guardians of Chelsea’s noblest house of prayer.

You your church’s vastness deplore

‘Should we not sell and give it to the poor?’

Recall, despite your practical suggestion

Which the disciple was who asked that question.

Betjeman said the central North Wall window by Sir William Blake-Richmond, with the theme of Youth and its sacrifice and joys, was ‘symbolising the hope that this great city may rise to the value of beauty, setting aside money and society as chief aims of life.’ Needless to say, Betjeman’s ‘noblest house of prayer’ was saved.

Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Square, was described by Sir John Betjeman as ‘Chelsea’s noblest house of prayer’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

After a long period of less symbolic worship, notably when the Revd Alfred Basil Carver was Rector (1945-1980) and the shorter incumbencies of the Revd Phillip Roberts (1980-1987) and the Revd Keith Yates (1987–1997), the church has returned to a liberal Catholic style of worship and liturgy.

The church now has a thriving congregation built when Bishop Michael Eric Marshall, former Bishop of Woolwich, was Rector (1997-2007). The connection with the world of the fine arts continued under the Revd Rob Gillion was Rector (2008-2014). He later became Bishop of Riverina in western New South Wales.

Holy Trinity has enjoyed a reputation for church music since its early days. John Sedding, also an organist, provided an unusually large chamber for the noted four-manual Walker organ. Notable organists have included Edwin Lemare (1892-1895), Sir Walter Alcock (1895-1902), John Ireland (sub organist, 1896-1904), and HL Balfour (1902-1942).

The organ was badly damaged in World War II, but was repaired in 1947 and partially rebuilt in 1967. Harrison & Harrison completed a rebuild in 2012, using the surviving Walker pipework and matching new material. The organ has 71 speaking stops and about 4,200 pipes, and remains one of the principal organs in London.

The relief panel on the west wall behind the font is to the design of Henry Wilson (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Today, the church sees itself as a ‘Shrine and Sanctuary’ for Sloane Square, and, for example, also provides chaplaincies to neighbouring places such as Harrods and the Royal Court Theatre. The parish of Saint Saviour, Upper Chelsea, was added to Holy Trinity in 2011.

Canon Nicholas Wheeler is the Rector of Holy Trinity and Saint Saviour. He returned to London from Brazil where he worked with USPG in the Parish of Christ the King in Rio de Janeiro and as a canon of the Cathedral of the Redeemer. His work in Cidade de Deus, one of the most disadvantaged communities in Rio, inspired the 2002 film, City of God.

Before going to Brazil with USPG, he spent 21 years in the Diocese of London, where his posts included Team Rector at Old Saint Pancras.

The Sung Eucharist is celebrated in Holy Trinity Church every Sunday at 11 a.m.

Holy Trinity sees itself as a ‘Shrine and Sanctuary’ for Sloane Square (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Labels:

Architecture,

Brazil,

Chelsea,

Church History,

John Betjeman,

Liturgy,

London,

London churches,

Poetry,

Pre-Raphaelites,

Pugin,

Ruskin,

Sculpture,

Stained Glass,

Theology and Culture,

USPG

Praying in Ordinary Time with USPG:

Wednesday 28 September 2022

All Saints’ Church, North Street, York, has been described as ‘York’s finest mediaeval church’ (Photograph: Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Patrick Comerford

In the Calendar of Common Worship in the Church of England, today (28 September 2022) is an Ember Day. The Michaelmas Embertide retains its traditional association with the autumn harvest.

Before today gets busy, I am taking some time this morning for reading, prayer and reflection.

This morning, and throughout this week and next, I am reflecting each morning on a church, chapel, or place of worship in York, where I stayed earlier this month after a surgical procedure in Sheffield.

In my prayer diary this week I am reflecting in these ways:

1, One of the readings for the morning;

2, Reflecting on a church, chapel or place of worship in York;

3, a prayer from the USPG prayer diary, ‘Pray with the World Church.’

Inside All Saints’ Church, North Street, facing the east end (Photograph Patrick Comerford, 2022)

Luke 9: 57-62:

57 As they were walking along the road, a man said to him, ‘I will follow you wherever you go.’

58 Jesus replied, ‘Foxes have dens and birds have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head.’

59 He said to another man, ‘Follow me.’

But he replied, ‘Lord, first let me go and bury my father.’

60 Jesus said to him, ‘Let the dead bury their own dead, but you go and proclaim the kingdom of God.’

61 Still another said, ‘I will follow you, Lord; but first let me go back and say goodbye to my family.’

62 Jesus replied, ‘No one who puts a hand to the plough and looks back is fit for service in the kingdom of God.

The chancel screen in All Saints’ Church was designed by the York architect Edwin Ridsdale Tate (Photograph Patrick Comerford, 2022)

All Saints’ Church, North Street, York:

All Saints’ Church, North Street, York, is described as ‘York’s finest mediaeval church.’ It is attractively located near the River Ouse and next to a row of 15th century timber-framed houses, and should not be confused with All Saints’ Church, North Street, which I described yesterday.

All Saints’ Church was founded in the 11th century on land reputedly donated by Ralph de Paganel, whose name is commemorated in the Yorkshire village of Hooton Pagnell.

Externally, the main feature is the impressive tower with a tall octagonal spire. The earliest part of the church is the nave dating from the 12th century. The arcades date from the 13th century and the east end was rebuilt in the 14th century, when the chancel chapels were added. Most of the present building dates from the 14th and 15th century.

Inside, the church has 15th-century hammerbeam roofs and a collection of mediaeval stained glass, including the Corporal Works of Mercy (see Matthew 25: 31ff) and the ‘Pricke of Conscience’ window, depicting the 15 signs of the End of the World.