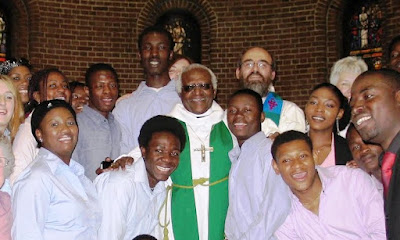

With Archbishop Desmond Tutu and members of the Discovery Gospel Choir in Dublin in 2005

Patrick Comerford

I was saddened to hear the news this morning that Archbishop Desmond Tutu has died at the age of 90.

When he received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984, I profiled Archbishop Desmond Tutu for The Irish Times. We had met previously, at events co-hosted by AfrI and Christian CND and at dinner in Roebuck House, Seán MacBride’s house in Clonskeagh, Dublin.

I asked him about the death threats he faced in South Africa at the height of apartheid. He engaged me with that look that confirmed his deep hope, commitment and faith, and said: ‘But you know, death is not the worst thing that could happen to a Christian.’

He must have been tempted at times to give up being a thorn in the side of the regime, to stop being a ‘turbulent priest,’ and to live a comfortable life. But his conscience would never have been comfortable.

As a young adult who had recently come to experience the love of God and started to explore the challenges of Christian discipleship, I was deeply challenged by the witness of one of his predecessors as Dean of Johannesburg, who opened the doors of his cathedral and offered sanctuary to black protesters who were being beaten on the cathedral steps by white police using rhino whips.

Dean Gonville ffrench-Beytagh knew the consequences. He was jailed, and eventually exiled from South Africa. To use the words of the German martyr, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, he bore the ‘Cost of Discipleship.’ Some years later, while apartheid was still in force, Desmond Tutu became Dean of Saint Mary’s in Johannesburg, and when I first met him, he was the secretary general of the South African Council of Churches.

I was worried about the many death threats he was receiving, and I asked him how he lived with those threats. Was he worried about them? Did he ever consider modifying what he had to say because of them? His answer was similar to the one he gave when he was facing tough questioning before the regime’s Eloff Commission. He told that inquiry:

‘There is nothing the government can do to me that will stop me from being involved in what I believe God wants me to do. I do not do it because I like doing it. I do it because I am under what I believe to be the influence of God’s hand. I cannot help it. When I see injustice, I cannot keep quiet, for, as Jeremiah says, when I try to keep quiet, God’s Word burns like a fire in my breast. But what is it that they can ultimately do? The most awful thing that they can do is to kill me, and death is not the worst thing that could happen to a Christian.’

With Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Seán MacBride and Bruce Kent in Roebuck House, Dublin, in the early 1980s

In 1987, Veritas invited me to write a short, 36-page biography of Archbishop Tutu, published as Desmond Tutu: Black Africa’s Man of Destiny. It was launched by the then Minister for Foreign Affairs, Brian Lenihan. It was a small book, hardly more than a pamphlet, but it came at an important time when both the Irish Government and the Irish Churches were becoming increasingly vocal about the evils of apartheid.

It was republished as a paperback in the US by Citadel in 1988 and by Hyperion Books in 1989, and when I was visiting South Africa in 1990 with The Irish Times and Christian Aid, I met him in Cape Town, where once again he spoke powerfully about the changes that were beginning to take place.

We kept in touch for many years, exchanging Christmas cards and greetings, and I have many of his signed books on my bookshelves.

Then, when my colleague Patsy McGarry was organising a monumental series of one-page features in The Irish Times in 2000 to mark the millennium, Archbishop Tutu was one of the international writers who contributed, along with Hans Küng, Andrew Greeley and Mary Robinson. The complete series was published by Veritas the following year as a book, Christianity, in which Part Two was my ‘Brief History of Christianity.’

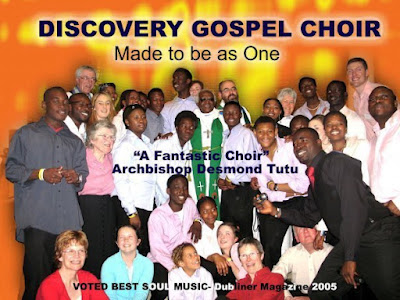

We last met when he visited Dublin in 2005, and he preached in Saint George’s and Saint Thomas’s Church in the inner city, where Canon Katharine Poulton was then the Rector, as part of the Discovery Gospel Choir services.

With Archbishop Desmond Tutu on the cover of a Discovery Gospel Choir CD

No comments:

Post a Comment